“This never happened to the other fella.” That might have been George Lazenby’s quip in the opening sequence of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), but it’s also become the rallying cry for the Daniel Craig era of Bond pictures, which began with him as an inexperienced, impulsive agent just earning his license to kill in Casino Royale (2006) and ends now with him as a weathered, embittered, desperately-in-love man in No Time to Die. In retrospect, it feels as if Lazenby’s cute, fourth-wall-breaking acknowledgment (reportedly ad-libbed on set by the star himself) that his post-Connery turn might be a different Bond perhaps liberated the series a little: Once that line landed, nobody had to worry about keeping any kind of consistency between Bond actors, or even individual movies.

Of course, within the actual Craig cycle, the inter-film callbacks and echoes and through lines have been nonstop — and not always for the best. At the start of No Time to Die, Bond is still grieving Vesper Lynd, his lover and partner from Casino Royale, while also committing to a life with Madeleine Swann (Léa Seydoux), the assassin’s daughter and psychiatrist he romanced (rather unconvincingly) in Spectre (2015). This new one even opens with an episode from Madeleine’s childhood that she’d related in that previous entry, only now it’s been revised to become our introduction to Lyutsifer Safin (Rami Malek), a psycho who went off the deep end after his whole family was killed by Madeleine’s father, Mr. White.

White was, as you may or may not recall from the previous film, an assassin working for SPECTRE, the international criminal organization led by Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz), the devious mastermind whom Bond made sure to lock up at the end of that picture. Staying true to our modern age of action movies-as-elaborate-soap operas, it also turned out that Blofeld — organ music, please — is Bond’s long-lost adopted brother. No, this definitely never happened to the other fellas.

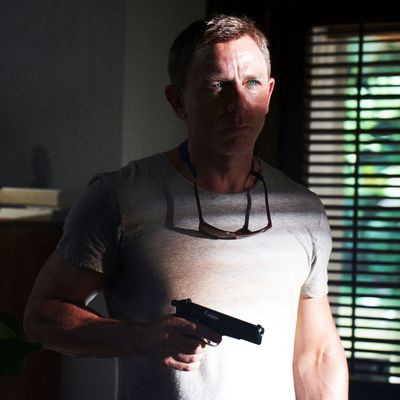

Indeed, the central project of the Daniel Craig era could easily be seen as an experiment to see how un-Bond-like one could make these films while still being able to call them Bond films. The experiment reaches its apotheosis in No Time to Die, which opens with Bond in love, then moves on to Bond betrayed, then Bond retired, then Bond working for the CIA, before bringing Bond back into the fold of MI6, where it turns out he’s actually been replaced by a new 007, Nomi, played by Lashana Lynch. (If you think those are spoilers, note that I’ve said nothing of Bond’s [redacted], his discovery of [redacted], or the dramatic [redacted]s of [redacted], [redacted], and [redacted].)

There are opportunities here, many of them missed: The two 007s have a playful rivalry at first, and one wishes the script featured more of their repartee. Lynch certainly seems game, with her character handling Bond with just the right combination of admiration and annoyance. And we know Craig has solid comic chops, as evidenced by some of his previous outings and by the levity he brought to, um, Steven Spielberg’s Munich (2005). If nothing else, Lynch’s 007 seems like a more interesting character for Bond to spend time with than Madeleine; the lack of chemistry between Seydoux and Craig really grates this time around, which wouldn’t be a problem were the film not built around James Bond’s passionate love for this woman. (Craig and Eva Green had it in spades in Casino Royale, which is why we can still buy the fact that Bond is visiting Vesper’s grave, four films later.)

One interesting note on the picture’s otherwise-forgettable (though refreshingly Bondian) MacGuffin: Everyone is after a bioweapon that uses nanobot technology to target specific individuals and anyone else who happens to share their DNA, and which Safin clearly has diabolical plans for. We all remember that No Time to Die was due to open in spring of 2020, right as the COVID-19 pandemic was hitting. News of the release being delayed was among the first signs that much of the global entertainment industry was about to shut down, along with just about everything else. One does wonder what it would have felt like in the middle of 2020 to watch a James Bond film about what was essentially a deadly virus being released into the world.

Some wondered at the time why this potential blockbuster wasn’t just sold to a streaming service so we could all watch it in the comfort of our homes as we did the dishes or folded laundry or doomscrolled Twitter or whatever. If you see No Time to Die on the big screen, you’ll have your answer. Director Cary Joji Fukunaga has not just a terrific eye, but also an intuitive knowledge of where to put the camera for maximum impact — whether it’s inside a bulletproof car that’s being strafed by what feels like a hundred gunmen, or a bird’s-eye view of Ana de Armas (playing a novice CIA agent, a brief highlight of the movie) spinning around in a high-slit gown knocking down baddies, or a handheld long-take following Bond up a stairwell as he pummels his way through a small army of henchmen, or simply a soaring aerial shot taking in the dizzying heights of an Italian mountain town. Shot partly on IMAX, No Time to Die is clearly meant to be seen on a massive screen.

Even that feels a little anti-Bond, frankly; despite their huge sets and international locales, these films pre-Craig rarely trafficked in grandeur or immersion. (I think I initially watched most of them on airplanes.) At times, the director seems to be leading us on a journey through the non-Bond action landscape — a Dark Knight sequence here, a Fast & Furious sequence there, a Fury Road sequence there, a Hanna sequence there, to say nothing of the Mission: Impossible style teamwork that we get when the two 007s start working together. (There’s even a Silence of the Lambs moment so ostentatiously — and possibly inadvertently — goofy that the picture briefly starts to feel like it’s one Wayans brothers polish away from becoming an elaborate, albeit overlong and expensive, spoof of all genre flicks.)

With all its connections to the previous film, No Time to Die’s biggest failing is probably the fact that it seems to think Spectre had a compelling narrative. But that’s sort of par for the course for the Craig Bonds, too. They extract their pound of flesh. To get to the next action sequence, we often have to sit through another interminable speech or exchange with the bad guy about how we’re both really the same, you and me. Craig has neither the ability nor the willingness to dismiss such blather with a raised eyebrow, as, say, Roger Moore could. Craig wants to commit, to emote, to really tackle the substance of the material; he is, after all, a real actor. Except that the material has no substance: It’s still the same tired nonsense, just longer, and all the added elements to give the story and the characters emotional heft mostly fail as a result. That in turn makes the picture’s forays into genuine darkness, particularly near the end, ring rather false. Still, amid the grit and the attempted emotional catharses and the Sturm und Drang, there is an actual Bond movie in there. No Time to Die is fun, but only when it dares to be.