About halfway through The Old Guard, Gina Prince-Bythewood’s upcoming film about a group of immortal warriors, something happens that I’m pretty sure has never happened before in a big-budget superhero comic-book movie: A man declares his love for another man. And it’s not just a corporate-approved, Disney-esque bit of tokenism, either. The men in question are Yusuf, a.k.a Joe (Marwan Kenzari), and Nicolo, a.k.a Nicky (Luca Marinelli), two members of the five-person team that gives the movie its title. In this scene, they sit handcuffed in the back of a van, surrounded by soldiers. Joe is checking to make sure Nicky is okay. “What is he, your boyfriend?,” one of the soldiers asks, chuckling contemptuously. Joe takes a long look at his captor and proceeds to give one of the most full-hearted declarations of love I’ve ever witnessed in a film.

“This man is more to me than you can dream,” he says, his voice trembling. “He’s the moon when I’m lost in darkness, and warmth when I shiver in cold. And his kiss still thrills me even after a millennium. His heart overflows with a kindness of which this world is not worthy. I love this man beyond measure and reason. He’s not my boyfriend. He is all, and he is more.”

Then the two lovers kiss, passionately.

The scene comes directly from the original comic book The Old Guard, by Greg Rucka, who is also credited with the film’s screenplay, and who stipulated in his contract that it had to be in whatever movie got made from it. Luckily for him, the person who made the picture was the director of Love & Basketball (2000) and Beyond the Lights (2014), two of the great romantic dramas of our time, films filled with the sweet despair of yearning. And she “would have fought to the death to keep that scene in,” Prince-Bythewood says, recalling that it was one of the reasons she wanted to do the film in the first place. It’s easy to see why: She makes movies that are textured with real-world detail, that take their time getting to know their characters’ hopes, fears, desires, even the kind of music they listen to. Her adaptation of The Old Guard is a superhero film like no other: patient, intimate, realistic — or at least as realistic as a movie in which Charlize Theron plays a 6,000-year-old warrior who splits dudes open with ancient weapons can be.

The Old Guard, which arrives July 10, makes Prince-Bythewood the first Black woman to helm a major superhero film. The journey toward making it, weirdly, began with an entirely different superhero film. In 2017, it was announced that she would be directing Silver & Black, a studio feature built around Black Cat and Silver Sable, two characters from the Spider-Man universe, for Marvel and Sony. (She proved her comic-book-genre bona fides on the small screen by directing the series pilot for Marvel’s Cloak & Dagger.) Prince-Bythewood would spend a year and a half working on Silver & Black. “I was pretty far in — we were developing costumes,” she says. “But we were just not agreeing on the script. I came in with a vision, and that vision never changed.” It was while she was wrestling with Silver & Black that the script for The Old Guard arrived like a lifeline. Executives at the production company Skydance, looking for a female director, had been impressed with her work in Love & Basketball and Beyond the Lights. “It was everything I wanted to do in this genre,” she says. “With female leads, one being a young Black female. It was edgy and real, but still had that fantastical conceit to it.”

Prince-Bythewood, 51, has a calm demeanor that can make it seem like professional and personal setbacks are no big deal. She’ll often chuckle when discussing all the time she’s spent on movies that never happened. She’s speaking to me from the room in her L.A. home where she does all her writing. Her husband, Reggie Rock Bythewood, with whom she often collaborates (the duo created and executive-produced 2017’s Shots Fired, a Fox limited series about police violence and community unrest in a fictional North Carolina town), has his own office on the other side of the house. Behind her is a standee from Love & Basketball and a poster for Noni, the fictional pop star played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw in Beyond the Lights. On the walls are stills from all her films, as well as a photo of Kathleen Cleaver with the Black Panthers. “Every time I sit down to write, I feel like I forgot how to do it,” she says. The pictures remind her, “Okay, you do know how to do it. It will come. Just be patient.”

The Old Guard is only her fifth feature in 20 years, a period during which she has worked in TV, developed a number of projects that never came to fruition, and struggled to tell the stories she’s wanted to tell, often with Black women at their centers. When I ask her to describe what she’s like as a director, she holds her hand up flat and draws a steady line with it in the air. That sentiment is shared by many of her collaborators. “She has this insular nature to her, and people sometimes don’t know what she’s thinking, which can be a good thing in this business,” says her longtime editor Terilyn Shropshire, who cut The Old Guard. They also observe an intensity and drive beneath that even-keeled serenity. “She’s deceptive because she’s soft-spoken, she’s shy, she’s a bit of an introvert,” says Sanaa Lathan, who starred in two of Prince-Bythewood’s films as well as Shots Fired. “Yet when it comes to something she wants, she will not take no for an answer — period, end of story. She will fight patiently and quietly, but she’s going to fight until she gets what she wants. And I’ve seen it time and time again.”

“Bernie Mac called me the Quiet Storm,” Prince-Bythewood says with a smile. “I actually really liked that.”

Prince-Bythewood was adopted as a baby in Chicago before her family moved to the picturesque town of Pacific Grove, California. “It’s an interesting mix of extreme wealth and working class,” she says. “And we were on the working-class side of it.” It was also an extremely white place. “There were six Black people total in my school, and one of them was my brother,” she says, noting that there was racism all around her. Her parents — who are of Salvadoran and Irish descent — suggested that if she ignored the racism, it would go away. It didn’t. “There wasn’t one person in my life, including best friends, that did not say something racist at some point,” she recalls. It’s one of the reasons she doesn’t use Facebook or keep in touch with any childhood friends.

Home wasn’t always a happy place either, mainly because of the chaos caused by a family member’s drug addiction. (She doesn’t want to say who it was because she now has a good relationship with this person.) “That dominated the house,” she says. “I didn’t like to go home because of that. I was afraid to go to sleep.” Prince-Bythewood remembers writing stories at a young age and realizing, “In stories, you could control the ending.”

She also found salvation in sports, television, and movies. She and her siblings — one brother, also adopted, and two sisters — had all started sports early. “There were so few girls, we always had to play with boys. We would get kicked on the field by little boys who didn’t want us.” She credits her parents for telling her never to leave the field. In high school, Prince-Bythewood lettered in eight different sports, though she was particularly drawn to basketball and track. “Racism wrecked my self-esteem, but sports gave me applause and made me feel great about myself,” she says. “The feeling of being able to dominate everybody on that court or track — that was my survival. There is a part of me that sees my success as a middle finger to everybody in that town who made me feel less than.”

Then there were movies and TV. She escaped into soap operas (“I was watching five a day”). She recalls the first time she saw Diff’rent Strokes, a show about two Black kids adopted by a white family, and thinking, Oh my God, that is my life. It was a pivotal moment. “It’s a big deal to see yourself onscreen,” she says. “Suddenly I didn’t feel as strange and wrong as I had been made to believe I was by my surroundings.” As a young child, she would ask her parents, “How can you love me the same as your kids that you had naturally?” They’d tell her she was special “because they chose me” (which she then used to lord over her siblings).

In high school, Prince-Bythewood was recruited by some colleges to play basketball, but she opted to go to UCLA because it had a film program, “knowing I wouldn’t be able to play ball anymore.” (Once there, she missed competition so much she joined the track team.) In her early years in college, working on student films and on a soap opera produced on campus made her realize she wanted to be a director. At the time, one had to apply to get into the UCLA film program in one’s junior year. Prince-Bythewood was rejected. “It was one of the worst moments of my life because I finally knew what I was supposed to do — and you get a rejection. What am I going to do now?” So she wrote an impassioned letter to the head of the film school, who “called me two days later and said, ‘You’re in.’ ”

After college, she got a job in the writers’ room of A Different World, working alongside industry veterans and getting caught up in its “sink or swim” atmosphere. She recalls Susan Fales-Hill, the show’s co-producer and lead writer, pulling her aside after a couple of weeks and telling her, “When we’re in the writers’ room, and you’re telling these writers their jokes aren’t funny or something doesn’t really work, that’s not really the way to do it. What you’re saying is right, but you can’t just say it — give a solution.” It was on A Different World that she met another young writer, Reggie Rock Bythewood, who was hired a week after she was. (“We had seen each other before at a taping of Fresh Prince,” she says. “We always laugh about this. He says I was checking him out. I say he was checking me out.”)

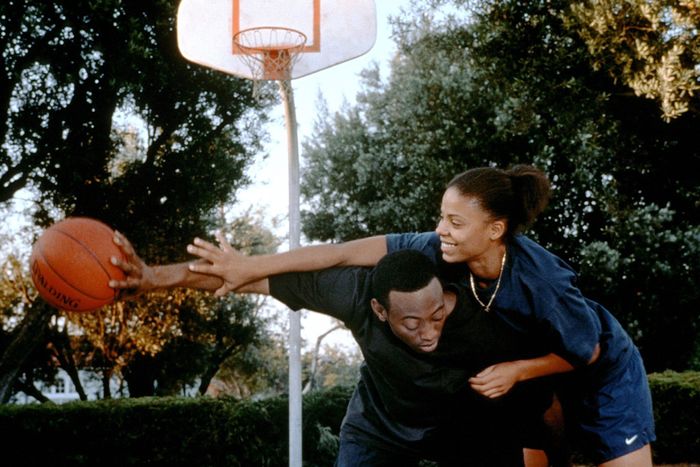

Prince-Bythewood continued getting TV-writing gigs and was working on Felicity when she got the chance to direct her first feature, Love & Basketball. The film went through the Sundance Labs but was initially rejected by nearly every company in town, until it came to the attention of a production exec with Spike Lee’s 40 Acres and a Mule. It tells the story of two hoops-obsessed friends, Monica and Quincy (played as grown-ups by Lathan and Omar Epps), who bond as children on the court, hook up in high school, and spend years pining for each other. The film’s lovemaking scene is acclaimed as among the most honest ever put on film, in part because it acknowledges the reality of body parts, and the complicated mixture of affection and pain that can occur during sex, and it does all this almost entirely by focusing on Monica and Quincy’s faces. If you outlined the story on a page or two, it might not sound like much. The closest thing it has to a climax is a late-night one-on-one basketball game in which Monica plays Quincy for his heart the night before his wedding to someone else. It’s a potentially ridiculous idea, but the scene is filmed with zero irony. As they play, a feeling of anguish sets in as we realize Monica might lose this game.

Love & Basketball was well liked by critics and modestly successful in theaters. It quickly gained a following on video, particularly among Black audiences, and came to be regarded as a classic within a few years. (Fourteen years later, something similar happened to Beyond the Lights.) Prince-Bythewood followed it up immediately with the touching Disappearing Acts, an HBO-produced adaptation of one of her favorite novels by Terry McMillan. It stars Lathan as an aspiring singer in Brooklyn who falls for a charming construction worker played by Wesley Snipes. The issues they face are hard ones — class, money, pregnancy — but it all plays out through the minutiae of daily life; things like a fixed tie, a choice of wine, the location of some concert seats gain seismic emotional weight. Prince-Bythewood is proud of the film, but she also says that she took on the job too quickly. “You need a break, and I didn’t take a break,” she says.

It would be eight years before she would get to make another feature film. During this time, Prince-Bythewood worked on a dream project, an adaptation of Wally Lamb’s best seller I Know This Much Is True, about twin brothers and the troubled emotional dynamics in their family. (“That relationship of the two brothers is what I went through personally,” she says.) The producers went after four name actors for the film, all of whom refused to meet with Prince-Bythewood, thinking she was a first-time director. She also had her own ideas about who would work best in the role. “I wanted Ryan Gosling, but that was before he was Ryan Gosling,” she says. “I couldn’t get people onboard.”

For Prince-Bythewood, finding the right performer is key to unlocking the movie she wants to make. In 2011, while auditioning actors for her next feature, Beyond the Lights, she met Mbatha-Raw, at the time a young British actress with only one U.S. feature role. “I saw the film while she was talking,” the director told me at the time. She became determined to make the film with an unknown. “She was incredibly committed to me as the lead actor,” says Mbatha-Raw, “even though executives, I’m sure, were convincing her to cast a big name.”

In all, it took two years to get Beyond the Lights off the ground. She and Mbatha-Raw spent much of that time immersing themselves in the music industry. The goal was to create a film that felt authentic to the psychology of those characters. At one point, before the start of production, Prince-Bythewood even sent Mbatha-Raw and the film’s male lead, Nate Parker, to have lunch in character. Dressed as a fictional pop star, Mbatha-Raw was besieged by autograph hounds and, eventually, a horde of paparazzi — all secretly sent by their director. Bedlam ensued. The actors had to flee the scene via the restaurant’s kitchen, running out a back door and into their car. “That was amazing, to have that in our muscle memory,” Mbatha-Raw recalls.

For The Old Guard, the cast went through intensive training to learn how to fight like people who’ve been doing it for centuries. Prince-Bythewood also made sure her actors read Dave Grossman’s book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, which she says argues that “taking a life is as damaging to the psyche as your fear of losing your life in battle or in war.” In order to make the characters feel real and to justify some of their actions, it was important that the centuries of killing had taken a psychological toll on them. Rucka credits Prince-Bythewood with taking the comics’ heightened, twisted, tongue-in-cheek style and balancing it out with a real moral gravity. “It’s an action movie, and you can still enjoy it,” he says, “but at the same time it actually interrogates the necessary question of what it means to take a life.”

In the film, the group gets a young addition, Nile (KiKi Layne), an earnest Marine who discovers her powers after getting her throat slit in Afghanistan and waking up in a hospital bed with the wound fully healed. Feeling lost and alone, Nile is alternately terrified and moved by what the Old Guard is capable of, and she becomes something of an audience surrogate for us. But she didn’t initially have much of a backstory. “Greg on his own had noticed that she did not have a full arc in the graphic novel,” Prince-Bythewood says. Learning to leave their families behind is a gauntlet that members of the Old Guard must reluctantly pass through, and Prince-Bythewood felt it was important to give Nile a history she agonized over.

Families — both actual and surrogate — are a running theme in the director’s work. When she was in her 20s, Prince-Bythewood reconnected with her birth mother, who is white, through the help of one of her sisters, a library-science major. “I paid so much money to different programs that said they could track down your family,” she says. “It was all a racket. My sister found my birth mother in like two weeks.” The relationship with her biological mom didn’t last. “She felt it was too difficult,” she adds. “I reminded her of that time.” Prince-Bythewood also learned that she had a half-brother and a half-sister: “My half-brother is nine months younger than me. So that was like, Wow, you gave me up, but you kept them.” When she asked her biological mom why she gave her up, she got an answer: “It was because I was Black and it was Chicago.”

One can hear echoes of this exchange in a scene near the end of Beyond the Lights in a monologue delivered by Noni’s mother and manager, played by Minnie Driver, when she recalls being a poor white teenager with a Black child. “I was 17 when I had you,” she tells Noni. “Black baby that my mom and dad wanted no part of … It felt like you and me against the world.” The mother and daughter clash, but the film ends with a promise of reconciliation. It is not a fairy tale — Prince-Bythewood takes real heartbreak and situates the story in a lived-in world — but it does build toward joy. “I need my films to have hope at the end,” she says. “We have an opportunity to envelop you for two hours. What are we going to leave you with? I want you to feel good. I don’t think that’s being soft at all.”

*A version of this article appears in the June 22, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!