Each month, J. Howard Rosier will offer nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

There was a thought that newspaper writing would subdue Clarice LispectorÔÇÖs famously knotty style like caging a tiger. No dice. If anything, the short pieces collected in this volume, which were written for the Jornal do Brasil from 1967 to 1973, are even more unpredictable than her fiction. No two columns are alike: strands of dialogue, observed scenes, diaristic entries, life advice, even the author admiring herself in the mirror. Given that the New DirectionsÔÇôled revival of her work has been underway for a while now, it isnÔÇÖt super-revelatory, but at 864 pages, Life is a huge addition to an already impressive collection of evidence that Lispector could transcribe a guestbook and make it interesting.

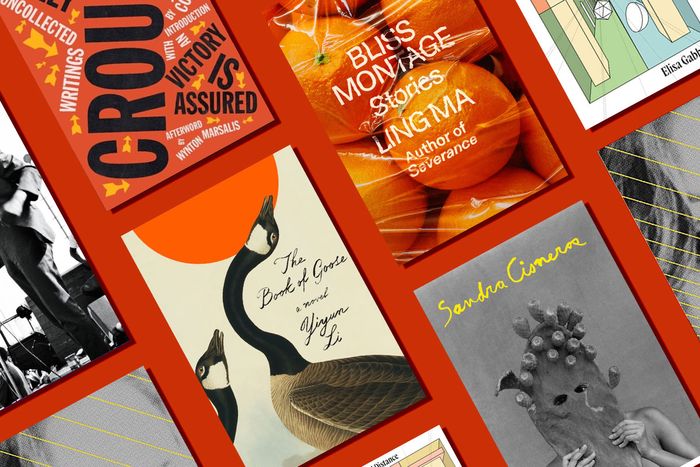

I was pleased that ÔÇ£The Electric Company,ÔÇØ Stanley CrouchÔÇÖs 2009 HarperÔÇÖs piece on a technology-assisted revival in Duke EllingtonÔÇÖs music, was included in Victory Is Assured, a book of the late writerÔÇÖs uncollected essays. It contains everything that is wonderful and frustrating about his writing. Terrific sentences, a wide breadth of subjects, but also a complete unwillingness to reconcile his vision of jazz as an American avant-garde with his utter lack of sympathy for avant-garde directions in jazz ÔÇö or in Black politics, for that matter. Yet itÔÇÖs doubtful that anyone circa 2022 would write something like ÔÇ£The Impeccable Sidney Poitier,ÔÇØ a tribute to the late actorÔÇÖs technique and influence, as well as an analysis of the impact of seeing someone with his skin tone on the big screen. You might think the latter is wholly contradictory to his suggestion that Lupita NyongoÔÇÖs speech on colorism, at the Essence Black Women in Hollywood luncheon, wasnÔÇÖt as valuable because the role she was honored for, as Patsey in Steve McQueenÔÇÖs 12 Years a Slave, was less humanizing. You might be right.

I wonder what Stanley Crouch wouldÔÇÖve made of this catalogue, considering his charge that the late activist ÔÇ£descended into the world of rabble-rousing.ÔÇØ Produced to accompany an exhibit of the same name at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, it does much to contextualize CarmichaelÔÇÖs media image as less of a misunderstanding than a coordinated attack by white elites spooked at the prospect of Blacks having any power not directly sanctioned by them. Parks, who had previously produced sympathetic photo essays about Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X in Life magazine, seemed the perfect artist to humanize Carmichael, whom he met in the fall of 1966 and followed through the spring of 1967. Digitally rendered pages of ParksÔÇÖs draft and resulting profile, ÔÇ£Whip of Black Power,ÔÇØ are included in the catalogue, along with the artistÔÇÖs photographs and contact sheets. When considered next to ÔÇ£What We Want,ÔÇØ CarmichaelÔÇÖs 1966 New York Review of Books manifesto, which is included, the gift that MFAH associate curator of photography Lisa Volpe has given readers is letting both artist and activist speak for themselves.

This long-awaited collection from the great Sandra Cisneros is laudable for its imagery but also for its synthesis of five distinct sections, which, except for the authorÔÇÖs voice, could have been five different books. Ultimately, the word that keeps coming to mind is tension ÔÇö between the Everymen and -women in the U.S. and Mexico she takes as her muses and the charming, elegiac, and introspective lens she turns on herself. SheÔÇÖs from Chicago, where Carl Sandburg memorialized mill workers and Gwendolyn Brooks sang of school-skippers, so I thought the heart of the matter would rest on the former. But a different tension rose and fell periodically before overtaking the book through satiation: eroticism. Hers, for sure (ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve died and risen / from the ash of my own / hesitation. IÔÇÖm creationÔÇØ), but also her motherÔÇÖs, Kasturba GandhiÔÇÖs, and, in one tour de force of a poem (ÔÇ£You Better Not Put Me in a PoemÔÇØ), a laundry list of lovers whose internal lives, and anatomies, feel achingly alive.

In her new story collection, Ling Mas narrative conceits are thoughtful enough to seem plausible yet open enough to lean into allegorical interpretations. Her assemblage of voices are by turns blunt (When you play stupid games, you win stupid prizes), hilarious (On the book-promotion circuit, I felt like the executor of a modest estate, interpreting and acting upon the intentions of the deceased  [b]ecause I bore her likeness), and insanely clever (It was all anyone associated with me; I became a waste bin of unsolicited sympathies). But what warrants its mentioning among the classic story collections is that, despite their variance in plot and approach, the stories in Montage feel like a true collection. Theyre less about environment or world-building than articulating a sensibility.

Agnes, the narrator of Yiyun LiÔÇÖs latest novel, sends readers through a gamut of emotions with her introspective and deceptively easygoing demeanor. I felt amused, anxious, protective, and ultimately heartbroken by her story. But fury: I was not expecting that. For her one-dimensional but realistically disinterested parents; Devaux, the widowed postmaster who concocts her childhood-prodigy image; Chastain, her publisher, eager for the next gimmick to sell; Mrs. Townsend, the unfulfilled and jealous schoolmaster who wants a genius to give her life value; but also Fabienne, AgnesÔÇÖs best friend, who sets the whole plot in motion by ghostwriting for her when the pair were children. Everything, down to FabienneÔÇÖs analogy of separation or violence, is so predetermined that you might want to throw the book across the room. But I couldnÔÇÖt, because I was waiting to see what would happen if Agnes went off the rails. Why it hardly matters when she does is worthy of several close readings, as is LiÔÇÖs manipulation of chronological time to blur the line between reverie and real-time thoughts. The Book of Goose belongs among a long line of books about writing that recognize how manipulative the act can be.

Quiet but thoroughly engaging, Elisa GabbertÔÇÖs latest collection of poems coaxes readers through observations, opinions, and declarations of facts. Carefully structured but rarely barreling toward a resolution, how its individual lines affect you might have everything to do with where your head is at any given point. Often very funny (from ÔÇ£DramedyÔÇØ: ÔÇ£When IÔÇÖm suffering I donÔÇÖt ask for help. / IÔÇÖm afraid theyÔÇÖll come and try / To take my pain awayÔÇØ), I landed most on the parts where Gabbert frames all the age-old preoccupations ÔÇö sex and death and love and time ÔÇö in a way thatÔÇÖs animate. ÔÇ£The Past is still. / The Future tremblesÔÇØ is sound philosophy in that it evokes the essential nature of the issue at hand, as is the idea of dying ÔÇ£when an asteroid hits my cryogenic chamber.ÔÇØ