Peacock’s Good One: A Show About Jokes is not your average comedy-documentary special. Over the course of seven hours of shows in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., Vulture writer Jesse David Fox and director Eddie Schmidt capture comedian Mike Birbiglia in a way he’s rarely seen: still figuring stuff out. After the Broadway run and subsequent Netflix special of his 2022 show The Old Man and the Pool, Birbiglia is back to square one, figuring out where he can possibly go from a show about death, and if you’ve ever listened to Vulture’s Good One podcast, you know that that sort of magical, awkward, open stage in a brilliant comic’s joke cycle is Fox’s favorite thing to dig deep on.

With unprecedented access to Birbiglia’s family, childhood friends, and writers’ room, Good One is a gift to comedy nerds. In an interview with the elusive Fox for Vulture (how on earth did we nab him?), he gets into what it takes to make a podcast a streaming special. It’s more about food than you think.

You’ve been making the Good One podcast since 2017. How long has a special been in the works?

I have an email introducing me to Eddie Schmidt, who would go on to be the director of this, from April 2019. That was exactly five years ago. We started pitching the show during the pandemic over Zoom, and then we filmed in April of last year.

The format of the special departs from the podcast. How did you figure out the format?

We had a million conversations. Early on, the podcast was not guaranteed to last more than, like, ten episodes. As soon as I knew that I was going to do more, I think I was aware of how it could be adapted. It was around the time that podcasts were being adapted for TV, and I was watching a lot of comedy documentaries and not loving them.

I was also watching a lot of food documentaries and thinking, Why can’t there be this for the thing that I know about? I wanted to do it like the show Mind of a Chef, where they get into the chef’s creative process. Or Chef’s Table, but Chef’s Table is too serious. So I thought of Ugly Delicious. Eddie was the showrunner for the first season of Ugly Delicious. I knew that there were things about the podcast’s perspective that would be better visualized, but I had no desire to be on-camera. So a documentary made the most sense.

What was different about making Good One as a 45-minute doc versus making it as a podcast?

We shot a ton — an unbelievable amount, or at least unbelievable to me, as a person who’s never made a documentary before. On the podcast, I go into it knowing the arc of the interview; I have my questions laid out, and then it’s done. Maybe we’ll edit things out, but the flow of the interview stays as is. With the documentary, there were so many different ways we could go: How do we want to structure it? Do we need narration? Do we need more talking heads?

How did you land on Birbiglia as a subject?

I’ve interviewed Mike before. I knew he was a process guy, and he has the most visual process possible. There was so much of his stuff around his offices. We’d be setting up a camera, walking around getting insert shots, like, “Zoom in on this joke on the bulletin board!” And because his process is so entwined with his personal life, it was going to be more than just a documentary about the mechanics of joke writing. It’s not just a guy going, “What if we change this word to that word?” There’s some of that, but it’s not only that.

If there’s a reason most people don’t have documentary crews around when they are creating something, it’s a really vulnerable position to be in. It’s really emotionally exhausting. So to do that, while also being asked to reflect upon your entire life, was a lot to ask of someone. But Birbiglia was game to have us around.

Was he self-conscious about you filming his joke-writing process?

Yeah, I think he was. Eddie did a good job of having as few people in the room as possible when it felt like a moment was genuinely happening.

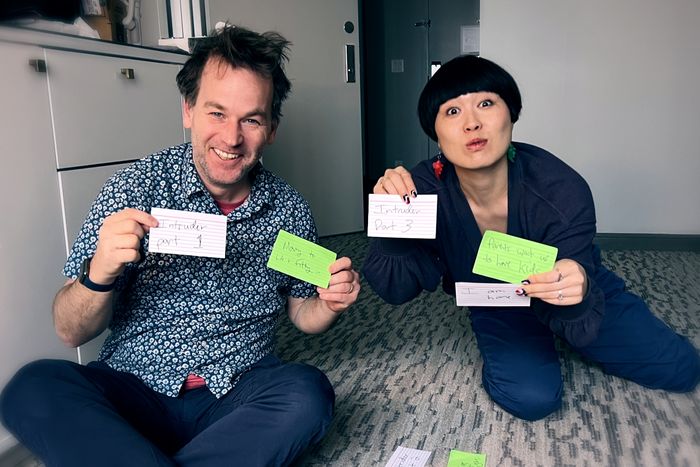

I think that the benefit of having a comedian as a subject is that no matter what, these jokes are meant to be performed out loud. So there was something organic about him writing these jokes in front of people the same way he’d tell them in front of people. They weren’t having fake meetings; these were meetings that they needed to have. That’s how he writes. I had a sense that there were other people involved; I always heard that his brother was involved, but I never really knew what that looked like. He is so unique in how he has essentially writing staffers involved.

You don’t think of a stand-up as having a writers’ room.

Or if you do imagine a stand-up having a writing staff, you assume it’s, like, Kevin Hart, surrounded by people on a private jet. But Mike has this little crew, and it helps that one of them is his brother. It’s helpful when you’re trying to tell a personal story to have family members involved. Like, his sister was selling merch at the Rhode Island shows with his nephews and nieces. You can’t put it all onscreen, but all of that stuff is texture. You get the feeling, even if you’re not capturing every part of it.

Good One features a lot of backstage footage and even some clips of his sets. Was he worried about giving away these sorts of things?

It was definitely a conversation that we had to have, because we wanted to use his material at a really early stage. Some of those shows, he’s reading stories out loud off of printer paper. That’s not how he intends on shooting it for a special. When you watch a special, it’s almost impossible to imagine that it started from nothing. And Birbiglia’s finished product is more finished than anyone else’s currently working. They’re so intricately put together.

Seth Meyers is a talking head in this, but what people might not realize is how involved he was as a producer. What was that like?

Seth really appreciates different comedic voices and is always talking about other comedians, so his role was partially championing the project and helping in conversations about the tone of it. He really has a good bullshit barometer. Like, look, I love Chef’s Table, but there is a lot of bullshit to it — that’s some of the fun. But you can’t do that when you’re making a comedy documentary; every comedian would be ashamed if it was as earnest as that.

What do you want audiences to take away from this special?

I want this to dispel the notion that explaining jokes makes them less exciting or less funny. I’m a zealot about how not true that is. And I hope that people leave it being more impressed by Mike’s work, but also more impressed by what a comedian can do — appreciating comedians as distinct artists, as opposed to the idea that Comedians are doing the same job, and that job is to make me laugh in this one specific way.

If you get an opportunity to make more Good One specials, who are some dream subjects?

There are other types of stories that we’ve talked about, like someone preparing for an awards show, or a musical comedian filming an album, or a physical comedian. Mike’s process makes a lot of sense. He has the journals, and the journals become note cards, and the note cards become pieces of paper. But we could find someone whose process is much more instinctual. Periodically, people will say things on the podcast that make me think, It would be cool to see that. Like, I remember Patton Oswalt saying he writes jokes when he does the dishes.

Anything else you learned by making the special?

As executive producer of a TV show, it’s not like I was super comfortable throwing my weight around. But we were shooting in D.C. right by a Nando’s, and I was like, “Man, can we get Nando’s for lunch?” And they were like, “Oh, we already have lunch plans.” But then they arranged for us to have Nando’s at the after-party-type thing. That’s the thing that they don’t tell you about when they adapt your podcast into a TV show: You do get some influence over what you eat.

That’s so great, Jesse.

It was cool!