This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It’s a rainy June afternoon, and most of the cast members of the new Gossip Girl are lining up to hit their cues for the Thanksgiving episode. It’s a classic Gossip Girl setup: a holiday designed to sow discord while supposedly being about gratitude. Zoya, played by Whitney Peak, the middle-class (and therefore comparatively underprivileged) freshman scholarship student who just moved to town, has found herself improbably rising in the school’s social ranks, which are ruled by her half-sister, Julien, played by Jordan Alexander. Zoya answers a series of knocks on her rent-controlled Upper West Side apartment’s door to reveal, much to her surprise, a steady stream of friends and enemies, some at war with one another.

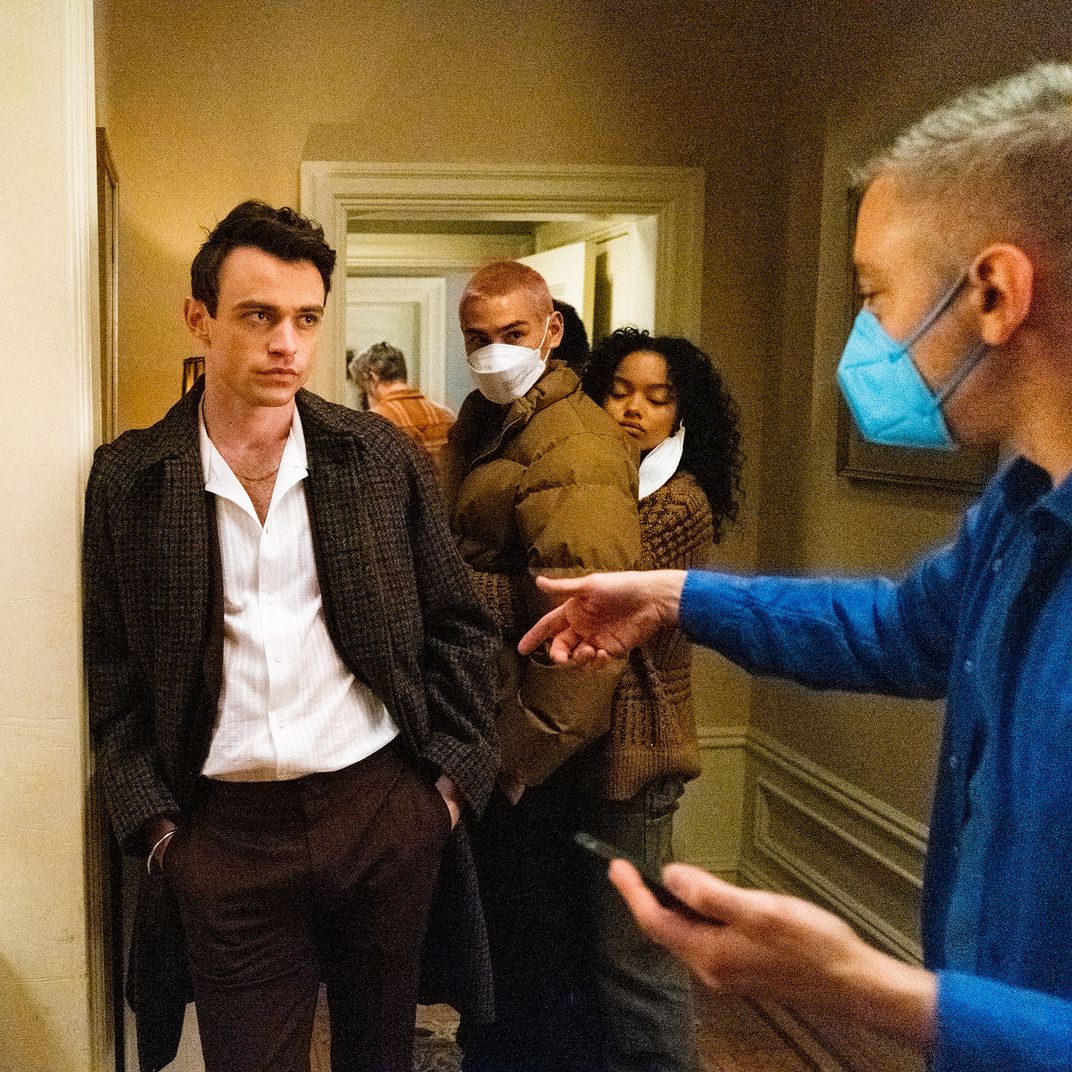

Fourteen actors float in the door and out of frame in one continuous shot. A camera operator starts spinning a wheel and the lens whips around to catch the spoiled-kid spectacle:

“What are you doing here?” “I asked you first!” “Did you know Max was — ”

a semi-estranged high-school couple huff in unison when their friend, who’s also the third member of a recent threesome, saunters through the door. “If we hurry, Dad, we can still make the 5 p.m. seating at Le Bernardin!” Julien, dressed in a slinky-shimmery dress, sighs.

“I was like, How many people? How much drama can I make?” says Josh Safran, the reboot’s showrunner and this episode’s director. There would be no Gossip Girl 2.0 without Safran, a New York City private-school alum who was a writer and executive producer on the first run of the show and dresses in monochrome. (“What’s today’s color?” I ask. “Pale pink?” “It’s more of a dusty rose,” he says.) He’s clever and meticulous about every detail. There should be more cracks in that character’s phone, he notes between takes. And shouldn’t that actor have more wine in her glass? He tells me that he has to feel overstimulated just to be stimulated. “I have, like, cocaine for blood,” he says matter-of-factly, which also pretty much sums up the tone of the show. “I don’t do cocaine because I’m afraid it’s going to neutralize me.” He thinks about the show for the 20 hours a day he isn’t sleeping, and he hasn’t stopped thinking about it since he abruptly departed the original, which aired from 2007 to 2012, right before its final season.

The original series — this one is technically a “continuation” — was wired on plot and subplot, schemes and betrayals (there was an SAT cheating scandal, and Serena, iconically and chicly, thought she had killed someone — just in season one), and was gonzo glamorous, often somewhat problematic (Chuck attempted a rape), and unapologetic in its worship of money and status.

The fantasy of the show is that these characters are 17-year-olds who, with the right mix of absentee parents and no credit limits, are allowed to act as adult as they want. These teens talk and sleep around and drink like grown-ups; the idea of adolescence, of not being taken seriously, is a nuisance. They wear heels and suits and plot corporate takeovers and teacher firings; they drink martinis at the Plaza to prove how adult they are. But the drama of it lies in the youthful foibles — a girl not liking you back, a brother you didn’t know you had, a mother who doesn’t appreciate your achievements — that any tenderhearted young person identifies with.

Safran knows all this: One of the things that hits you right away this time around is how the students are conscious of their privilege (which doesn’t necessarily make them nice about it). The show’s writing is aware that young people, the target demographic, are far more politically engaged — even, the bet is, with their escapism. When Gossip Girl herself, still voiced with Kristen Bell’s coo, is suddenly resurrected in the first episode, instead of being a blogger with Edith Wharton pretensions, she’s on Instagram, waggling her finger at the opulent hypocrisy (and maybe tinged with some of the current digital culture’s vigilantism).

Yet Gossip Girl remains a show about clout-chasers and backstabbers growing up and growing apart, good sex, bad parents, and carrying the right handbag. The point was never who Gossip Girl was. The show is about people who try desperately to be good but are unable to resist their worst inclinations. The point is drama heaped on top of drama, topped off with a few scoops of chaos. It’s not real life; it’s Gossip Girl life. The requirement at the door is that you take to bedlam like a pig in perfumed slop.

It may seem like a strange idea to bring back a status-obsessed show like this right now. Various Gossip Girl spinoffs and brand extensions never amounted to much since the original went off the air. The source material, a YA book series by Cecily von Ziegesar, was spun off into The It Girl. A backdoor pilot of a parent’s origin story was positively received but not picked up. Gossip Girl: Acapulco lasted a single season. Still, for the show’s creators, Josh Schwartz and Stephanie Savage, the idea of a reboot was too tempting not to attempt. “Would it be the same cast?” says Schwartz, who is an executive producer on the new show. “We explored a couple of different options with writers that we hadn’t worked with prior.” Ultimately, that idea was abandoned; the story of that quintet was done. Then, Schwartz says, “we had this conversation of, like, I wonder what Josh Safran is up to?”

Much of the first run of the show had Safran’s fingerprints all over it. He graduated from Horace Mann. Nate Archibald’s relationship with his tormented father is based on Safran’s own family. “Growing up, I didn’t know how much our apartment was on the Upper East Side,” he says. “I had no idea. I just knew it was on a low floor in a bad building, so therefore it was less than my friends’.” The show is at the intersection of everything Safran has been consistently good at throughout his career: New York City, teens, soapy high jinks, a balance of sarcasm and farce, keen observations of the upper class from someone who grew up near big money but not necessarily with it. He has worked on other popular shows but none so buzzy and Zeitgeist-y as this one about a lonely-boy blogger snitching on his friends.

Safran left the original Gossip Girl to run the short-lived (but much obsessed over) NBC musical series Smash. Even as the creators considered what Gossip Girl’s next life could look like, Safran didn’t see a future. Some of its stars went on to do movies, a few auditioned for Marvel, Blair married The O.C.’s Seth Cohen. Penn Badgley bravely complained every single chance he got about being typecast by the show. And Safran was harboring some regret over leaving before the final season.

Safran, who has been divorced, compares it to a divorce — not because there was any messy, door-slamming animosity but because he was so emotional about leaving: “I didn’t think they’d have me. I mean, I left. I felt like I left my wife or my husband.”

Savage and Schwartz seem bemused by this comparison. “He really loved musicals,” Savage says. “And we were like, ‘Great! Go do that!’ ” In the meantime, the world of TV had been upended by streamers. WarnerMedia, which owns the CW Network, home of the original Gossip Girl, launched HBO Max and was looking for marquee series in an effort to catch up with Netflix and Disney+. “I actually think Warner Bros. started the whole YA genre,” with shows including the first Gossip Girl, says Casey Bloys, the chief content officer for HBO and HBO Max.

And so Safran and Savage and Schwartz met over breakfast. Safran was working on another music-heavy passion project, the Netflix series Soundtrack; he hadn’t ever watched Gossip Girl’s last season, only the finale (he eventually saw it all when he took the job on the reboot). The Gossip Girl world was still delicious and relevant — its surveillance state is extended beyond rich kids in the back of Meatpacking District clubs to, well, everyone in every tax bracket — but how to update it? “And then I had this idea that occurred to me, and I couldn’t let go of it,” Safran says. “I thought about it all weekend. I came back to them, and I said, ‘Okay, let me run with this idea and see if I can make this work.’ ”

I’m not allowed to tell you what that idea was, but it works. Safran found his way back into this glitzy, glimmering, gossipy world, and he did it on his own terms with the full backing of HBO Max.

“When Casey took over [the streaming service], the show got an added lift to it,” he says. “Just a little more attention. As opposed to it being one jewel in a crown of many jewels, it became the crown.” (When I tell Bloys this, he laughs and insists Gossip Girl is a jewel among other jewels.)

“The first time, there were no expectations,” says Savage. “Nobody knew what the show was. We had to beg every location to let us shoot there.” On the original run, for example, they might have noted in a script that Dan and Serena would have dinner at Balthazar. “That would be the hope in the script!” Safran says. “But it would end up being some bistro we wouldn’t even name.”

The new show spends the kind of money the old show could only dream of its characters having. “He was like, ‘I need to elevate this,’ ” says Cassandra Kulukundis, the show’s casting director and Safran’s longtime friend. “He had so many lofty ideas, and he has such high-end taste. He’s like, ‘I don’t want people thinking it’s going to be this teen soap opera. I really want to make it the HBO way.’ ”

“My thing was always like, ‘Succession is where the world is right now,’ ” says Safran of the lavishly produced HBO show he wanted to match for oligarchic verité — and now he has the budget to do so. “So what’s the Succession version of Gossip Girl?”

Expectations are high: During production, the show’s ten-episode order was extended to 12, with six dropping weekly starting on July 8 and six dropping in the fall. A second season seems inevitable.

Gossip Girl had always been a show about money and the way people with money skated around Bloomberg’s New York City. The first show whimpered about rich-people problems, which worked for that time. The new generation has just as much money and privilege and access, and its members still take a lot of it for granted — they’re teenagers! — but part of their coming of age can include deciding how much the money matters to them. “These kids, they don’t know where a door is. They don’t even know where a bathroom is,” Safran told Karena Evans when she was directing the pilot. “Somebody opens the door to their car, somebody opens the door to the restaurant, somebody takes them to their seat.” Last time around, the richest kid was the most guilty and the most redeemed. This time around, the richest kid feels the most guilt over his parents’ substantial earnings.

“Kids know how much money their families have,” Safran says. They know exactly how rich they are, what they can buy, and what their friends can buy.

He makes another Succession comparison: On the old Gossip Girl, not having money was seen as a moral shortcoming; the new Gossip Girl looks at wealth with pointed jokes.

It’s therefore a bit more sophisticated. The old show “was a little soapier, a little twistier. It wasn’t camp, it wasn’t not-camp, but it also wasn’t camp on purpose,” Safran says. “It was a descendant of Dynasty and all of those shows. The girls pushed each other in a fountain, someone pushed someone into the Seine. This version is more like a comedy of manners.” The entrance scene they spent so much time on is closer in tone to a Billy Wilder comedy or the party scene in Breakfast at Tiffany’s but with Pete Wells–esque zingers.

What’s more: Safran knows where he wants everyone to eat, to live, and to hang out. These are characters who would eat at Frenchette and Le Coucou, so they actually needed to shoot at Frenchette and Le Coucou. There’s no more of the Humphrey-loft shenanigans that drove New York’s original Gossip Girl recappers so nuts — where there’s a home that’s supposed to be in Williamsburg, but the exterior shots are all from Dumbo. When Safran went scouting for streets with his locations manager, Matthew Kania (who also, it should be noted, worked on the first season of Succession), he was adamant about the most minute details. “Josh has actually been pretty specific about not just where these characters live but the direction they’re walking from: ‘No, no, no. They should be heading west if they’re coming from [this character’s] place,’ ” Kania recalls. Kania felt as if their first scouting trip was more of a quiz to test how well he knew the city. “Was it?” I ask Safran later. “Well,” he begins. “Yes.”

Safran’s wishes now have Kania happily in a tizzy. Is there an arms race of sorts between the Gossip Girl people, the Billions people, and the Succession people? “It’s not uncommon that we might be butting heads looking at the same restaurants, because there are only so many restaurants where this type of person would eat,” he says. “Same thing with penthouses, townhouses, and everything else — there are only so many places where people who have that wealth go.” He’s quick to clarify that Gossip Girl’s vision of New York City as a playhouse for the wealthy is different from the other shows’. Gossip Girl is about rich, style-obsessed people with taste, not just rich people with money and nice clothes.

The original show had a Jared-and-Ivanka cameo that may be cringey to some in retrospect, but it made sense at the time. That’s the kind of status the characters were obsessed with, the kind of people they rubbed (sharp) elbows with. In the reboot, one character carries a copy of Slave Play, and another wears a slinky Mugler catsuit and does bumps at a club. “If it’s a fashion show, it’s at the Armory. If it’s a black-tie gala, it’s at Manhatta, the highest restaurant in New York,” Safran says. “If it’s a play, it’s a Jeremy O. Harris play that he wrote for us that we actually shoot at the Public Theater.”

The original Gossip Girl cast descended on the city like a pack of distinctly beautiful, distinctly charismatic (and, in one case, distinctly eye-roll-y — but hey, he grew into it!) darlings. But none of them was famous. They had bounced around some other YA properties — Blake Lively had done The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, Chace Crawford literally worked at an Abercrombie & Fitch — but none was a household name. The first time New York sent emissaries to a Gossip Girl set, in 2009, there was a rumor that a publicist for the show had sent tips to “Page Six” to juice the cast members’ chances of breaking out as actual socialites. (“Promoting a show about gossip with gossip is not the worst idea in the world,” a shrewd magazine editor observed at the time; for its part, HBO Max PR denies that this ever happened.)

They were beautiful and perfect and delightfully mouthy (Lively asking if New York is “supposed to be classy” is forever quotable) but, most important, they were ours. Meaning they were Gossip Girl’s. Meaning they were a collection of perfect smirks, perfect sighs, perfect Cleavage Rhombuses, perfect sneers. They went off to Marvel, to uptown bookstores, to movies with iconic, status-affirming directors — and yeah, Leighton Meester should have been the breakout star, but God, like Gossip Girl, makes her mistakes.

So the question, all these years later, becomes: How do you capture teen-idol lightning in a bottle of Moët twice? Casting, Kulukundis says, is a quilt; you have to stitch together chemistry, talent, beauty, and basic logistics. Can they play this age? Can they work these hours? Do they want the Chanel campaign Gossip Girl can get you? Do they want to do a movie in a year? COVID complicated the process, leaving many roles to be cast without in-person chemistry reads. Kulukundis put out an open call to cast the subjects of Gossip Girl’s musings. She landed on a pack of exceedingly pretty youngsters, including a mix of professional actors (Peak, Alexander, Emily Alyn Lind, Zion Moreno); someone who looks like Chuck Bass’s younger brother (Thomas Doherty); someone who looks like Dan Humphrey’s younger brother (Eli Brown); a newly minted NYU graduate (Savannah Lee Smith); and a skateboarder-influencer with pink hair (Evan Mock). There’s also former Rookie editor Tavi Gevinson, now playing a flustered teacher.

Too many actors came in wanting to play a version of Blair or a version of Serena. (How many people auditioned wearing headbands? “There were a lot,” Kulukundis says. “There were little plaid skirts, little jackets. I didn’t even think young people had pearls.”) The old archetypes remain, but those characters don’t. Obie (Brown), for instance, has Dan’s self-righteousness and skepticism, but he’s a guilty rich boy living in a Dumbo penthouse, not the Williamsburg-dwelling son of a rocker making money off bad art and ’90s nostalgia. Audrey (Lind) is the closest to Blair in style and temperament; her shortest lines can land like spears through the gut. But the character is a caretaker uninterested in power grabs. Her somberness is a little closer to the surface. She is more openly insecure.

“You can see the similarities in some of the characters,” Kulukundis says. “But then we blur it. I think we allow them to be familiar to bring those [viewers] back and then we just blow it up.”

The teen glitterati are more racially diverse this time around, a perfectly obvious fact that everyone on the show will tell you all the time — seriously, constantly. When characters have threesomes, they can be same-sex, and no one freaks out about it. There are cameos from the playwright-model-screenwriter Harris and the designer Christopher John Rogers. Gossip Girl is now a show with two Black girls at its center, both as plotting and ebullient as the original S and B, but making them sisters takes the dynamic of their relationship to a new depth. We see one get into bed with her hair tied up in a bonnet. “That’s the biggest example of the evolution with Gossip Girl,” says Evans, who directed the first two episodes. (Safran told me he was so obsessed with Evans — who made her name as a director shooting music videos for Drake that aren’t cloyingly Drake — that he tried to cast her. She politely deflects the question.)

Kulukundis jokes to me that her dexterity as a casting director equips her to be a good matchmaker, too. Did she make a match in this cast? “No, no, no. I don’t know. We’ll see.”

Back on the Thanksgiving set, Safran hasn’t slowed down. In between the scenes and the approvals and figuring out how many cracks should be in the Android, I catch him tweeting. “Things are happening, things are happening, things are happening,” he says about a dozen times in a row. On Twitter, he has been teasing fans with Q&A sessions in between setups just to pass the time. A show that would normally take eight months to shoot has, because of COVID, taken twice that long. Maybe it makes it feel more real, like one day it will actually come out.

All this authenticity about the difference between one restaurant and another, I ask, about shooting at this or that place and making sure the characters are walking in the right direction in street scenes — is that for New Yorkers, is that for teenagers, or is that just for him?

“In my mind, the best shows are specific. If it’s generic, on some level you can feel it. Unfortunately, I do think you can tell when you’re trying to make something look like something it isn’t. And so I feel like here, with HBO’s blessing, we have the ability to make the show feel right, and even if you just don’t know the difference between Frenchette and another restaurant, you can feel the detail that was put into Frenchette so that it comes across on the screen,” Safran says, wiping his brow. “And if it doesn’t, and if nobody knows, then it’s just for me to be able to sleep at night knowing that Julien went to the restaurant that she’d actually go to.”

Gossip Girl premieres on HBO Max July 8.