Gus Van Sant arrived as a director 35 years ago with Drugstore Cowboy, a movie about goodhearted but self-destructive eccentrics who live one day at a time and make it all up as they go along. Over the decades, Van Sant, now 71, made more films about those types of people: the Shakespeare amalgam My Own Private Idaho and Uma Thurman oddity Even Cowgirls Get the Blues; Good Will Hunting, the Oscar-winning drama about a janitor who’s a secret math genius; Last Days, starring Michael Pitt as self-destructive rock star circling the bottom of the drain. It feels inevitable, then, that the stylish humanist would direct multiple episodes of Feud: Capote vs. the Swans, the Ryan Murphy–produced FX miniseries about the fallout from the alcoholic In Cold Blood author’s decision to use embarrassing true details about the private lives of his socialite friends as fodder for a novel he never finished.

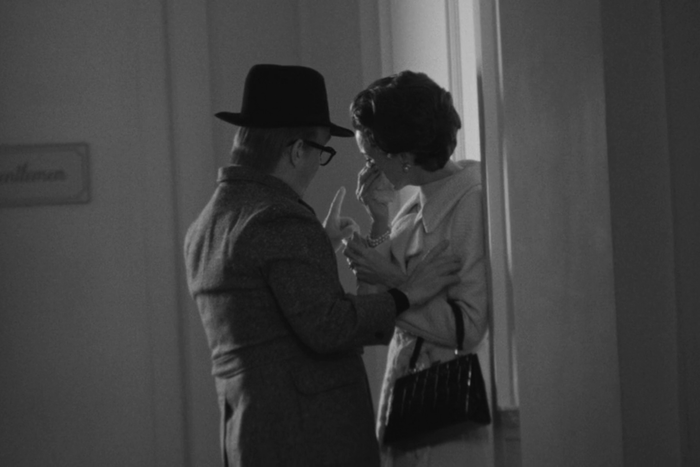

The stylistic peak of the series is third episode “Masquerade 1966,” an account of the planning and execution of what Truman (Tom Hollander) hopes will be the social event of the season: the Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel. He frets over the decor, publicity and guest list with counsel from the socialites he called the Swans (including Naomi Watts’s Babe Paley, Diane Lane’s Slim Keith, and Chloë Sevigny’s C.Z. Guest) while making what would prove to be catastrophic errors in judgment, including leading several swans to believe they’d be his “guest of honor.” (That title eventually went to non-socialite and Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham.) Van Sant and his collaborators crank up the anxiety by shooting in the style of Albert and David Maysles and other mid-1960s documentarians who practiced the Direct Cinema aesthetic: black-and-white, handheld, favoring immediacy and reportage over gloss and precision. It’s a directorial version of character-acting Van Sant traces back to his shot-for-shot 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

What are we looking at in episode three? It’s not a recreation of the Maysleses’ real documentary from 1966. That doesn’t have anything from the Black and White Ball in it.

It’s supposed to be a rough cut and Truman decides what goes in. It’s not a fine cut, it’s an assembly: outtakes or things that might not make it to the end result. And in the end, he’s deciding just not to do it. The Maysles brothers did something else with Truman, never the party. They went out to Long Island with him.

Is it true that Capote had editorial control over the Maysles film, or was that a conceit invented for this series?

It was invented. They never shot the ball and Truman never had editorial control. That idea was established in the series so he had the ability to cancel it. It was a way to say, “He wanted to write about this instead.” We were also supposed to notice that Truman was not being a good guy. The filming was making him look bad. That was also in his head.

Was there any indication that Truman Capote and David Maysles had a little something going on in real life?

We were suggesting that, but I don’t think that had any basis in reality.

How did you think about directing “Masquerade 1966”?

I’ve watched the work of a lot of documentarians, particularly ones who were part of the same movement as Albert and David Maysles. There was also D.A. Pennebaker, and Frederick Wiseman and Richard Leacock. The films they made were always fascinating to me. They were informing the French New Wave, partly, and by the 1980s, their work influenced MTV videos, as well as films like Oliver Stone’s JFK, which utilized MTV-style camerawork that was emulating the work of documentary filmmakers from that period.

Interesting that it ultimately became a “style.” I don’t know if the originators thought of it that way, did they?

Filmmakers like the Maysles and Leacock were just shooting that way to make their world a little bit easier — by getting rid of the tripod, pretty much. Leacock’s mentor was the director of Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty. Flaherty was the godfather of all of it because he was working with non-actors that were being positioned so that they were acting, in a way. The result was ultimately a documentary-style portrait of a place and a people.

Once we set the action, which was just blocking, it was all about acting and reacting to the actors, moving around the space they’re in in the fashion you want them to move in, emulating some sort of reality. If you construct that reality properly, it really doesn’t matter where you put the camera. If it’s a reality that makes sense, you could shoot it from the corner of the room with your phone. That’s what those documentarians were doing: They went to a location and put themselves someplace, and it was usually the wrong place in relation to where the action was going to be, so they’d have to zoom in to get to the shot they needed. Or they’d try to run over there, though sometimes they weren’t able to do that. A lot of times they got a bad shot. But it was the action you were looking at anyway. You can kind of force yourself into their situation: Once we got the action going, we might tell the camerapersons, “Just go for it. Get whatever you can get.” And it would look great and we’d go, “Okay, we got it.” Or we’d change it.

How did you make the documentary camerawork seem plausible for that period?

The shots the Maysles were getting in their documentaries weren’t what we think of as the “handheld” style today, which is kind of [makes a square with his index fingers and thumbs, then wobbles his hands] moving it around a lot, to make you think, Oh, this is handheld! That was an affectation that came about because of MTV. I had to tell the camera people, “Those people were holding the camera with their hands to make it easier to get the shots they wanted.” If the Maysles could put a camera on a tripod, they’d put it on a tripod. If they were shooting an event like Altamont for Gimme Shelter, they’d put the camera on their shoulder, but they’d try to make the shot as steady as they could.

How do you keep all the performances in period?

It was up to the actors to keep things accurate. Sometimes our references were our parents: How they moved and acted and how they spoke, even. If you could find a home movie of your parents from the ’60s, you’d be very surprised to see dad holding a gin and tonic on a Sunday morning. We were all chipping in as far as what those things would be.

Did my eye deceive me, or are there shots from the actual event in there?

There were a few shots from newscasters of the arrival of some of the guests. And there was a bit of a Charles Kuralt piece from CBS, in the hallway showing the guests arriving.

You had no shortage of film and video of Truman Capote, but was there difficulty in recreating the other major characters in terms of documentary accuracy?

Strangely, Babe was really hard. There just weren’t very many moving-image records of her from that time. I say ‘strangely’ because her husband was Bill Paley, the head of CBS! In researching her, we saw a still of her on a news set and we thought, Oh, did she actually deliver the news at one time? But no. I think somebody just took a publicity shot of her that way. She was a model for a while, so there were still images of her, but no moving images. I also never saw moving images of Slim Keith or C.Z. Guest.

For what it’s worth, everything felt real to me in your episodes, in terms of how people move through space.

Oh, good! You know, sometimes I’m not doing anything because what we’ve got is already working! That’s another thing I learned — if it doesn’t look rehearsed, just freeze that, because once you start perfecting it, it becomes less believable.

So if the actors are moving in a way that’s natural and the scene is working, you leave it alone and just shoot it?

We did that a couple of times, yeah. Harris Savides and I did four films together, and one time we were working on Milk, on a scene with like nine people in it, in a small room. They were preparing the camera in the same space where we were blocking the scene, and I noticed Harris had the camera in a certain position. I said, ”Oh, is that where you want the camera? Why did you pick that spot?” And he said, “Oh, no, no — the camera just fell off the truck here!” Sometimes that would happen, and wherever the camera happened to be, that was where we’d put it. Which is always an attractive notion, that it’s random. That means it’s unexpected. So we’d select the lens and say, “Let’s just leave the camera here first.”

And see what happens?

Yeah! Like, let’s try to do the scene first from wherever they happened to be when they were setting up the camera.

Are you thinking there might be some cosmic, unspoken logic to the camera ending up in that spot?

I’m thinking of it being unplanned. If you don’t want it to feel too planned, already having the camera in an unplanned position amounts to a free pass. Just go ahead and use the solution that’s right in front of you.

Did you follow the same line of thought when you were directing the third episode? I’m reminded of 24, which used handheld cameras; somebody who worked on the show told me they would sometimes keep the camera operators off set until they were done blocking a scene in order to make them scramble to capture the action.

We would do that exact thing. We would just not let the person shooting the camera know what was gonna happen, so it would feel as if a documentary situation was coming up.

In comparison to “Masquerade, 1966,” your approach to the first two episodes of Feud feels simple.

Simple in the sense of the shots?

Yes.

That was mainly a function of the shooting schedule and the budget, which was weighed down by the burdens of locations, set building, and costumes. There was a limited amount of money at that time from Disney. They gave me eight-and-a-half shooting days per episode, which I didn’t question; I just did it and made it work. But I had to give myself a method with which it could also be something original.

The first scene I shot was Slim Keith giving C.Z. Guest the necklace from Babe Paley, because Babe is counting on dying and giving away all of her jewels. C.Z. is walking the horse as they’re talking. The first shot was in the morning. We were out on Long Island. We were testing how fast we could do things. It was originally going to be an interior scene, and I said, ‘Why don’t we have this happen instead?” Chloë didn’t particularly know horses, so she wasn’t going to ride, but it was still risky to involve a horse. We planned it because we had the right equipment to do a shot like that. It all worked like we’d planned it. We always tried to always have an interesting shot that could work as a “one shot” piece, meaning no cuts, and then add to that until there was no more time left to shoot the scene.

Why did you do it that way?

Because if you’re cut off in terms of time, you at least have that master and, generally, at least two more shots that can complement the master. We’d always make sure to have that master run the entire length of the scene. So if it’s a five-minute scene, we have a five-minute master angle, and it won’t just be a section of the scene, it’ll be the whole thing.

Did you ever get to meet Truman Capote?

No. I wish I had. He and Tennessee Williams would have been interesting — just to see them speak. I did see Tru, starring Robert Morse, which was probably very close to seeing Truman speak. Morse learned the voice by studying recordings of Truman.

Was your first exposure to Capote through his written work, the adaptations, or Capote the celebrity?

The first exposure would have been the movie To Kill a Mockingbird, which came out when I was 10. There was this whole idea that the character of Dill — the next-door neighbor boy, who was painted in an odd fashion in the book and movie — was Truman Capote, who of course knew Harper Lee growing up. For the movie, they had cast this little character-actor boy who had been in a lot of TV, like Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Star Trek. He was a somewhat foreboding character. I was aware that Dill was a real kid who existed and that may have been what alerted me to Truman’s existence. This was a new idea for me, that you could have versions of real people existing as characters in fiction.

When “La Côte Basque, 1965” was printed in Esquire, I had a subscription, so I read that. When Robbie Baitz mentioned he was working on the miniseries, which happened during one of my first times hanging out with him, I was curious about how they were gonna do it, and whether they needed somebody to direct it. I knew the architecture of the story enough to think it was gonna be really good, at least for me, otherwise I wouldn’t have offered to direct it. There was no script yet. There was just this concept.

Were you involved in the structuring of the story?

No. I wanted to be, but I think Ryan’s style was that he constructed the outline first and Robbie used that to write from. I wasn’t really involved except for reacting to Robbie’s drafts. One of the first things I did was get ahold of the four stories from Answered Prayers and read them. I realized, Oh, this could be a P.B. Jones extravaganza, which is an idea that doesn’t really surface until later episodes. I thought the finished project might have ended up resembling Midnight Cowboy or something, which of course would have been a really different series.

The melding of reality and drama is something you’ve been grappling with throughout your career, whether you’re giving William S. Burroughs a supporting role as, basically, William S. Burroughs in Drugstore Cowboy, or interpreting the life of Harvey Milk, or shooting Elephant and Last Days, which are reactions to Columbine and the death of Kurt Cobain but not docudramas. How would you describe the evolution of your aesthetic, visually, in terms of striking a balance between real-seeming but also aesthetically interesting?

I always try to make a story conform to the reality as I know it. When I first started out with Drugstore Cowboy, I was putting so much emphasis on blocking. I came to that film off Mala Noche, which was storyboarded, so it was coming from a Hitchcockian idea of film storytelling: This is constructed, and this leads to that which leads to that. On Drugstore Cowboy, the crew was slower, so what I’d storyboarded just wasn’t gonna happen. I ended up doing it in the way I understood Stanley Kubrick did his filmmaking: He would work on a scene first and would figure out the shots afterwards. After that, I started working in that manner.

As I got more familiar with my cinema, the blocking started to become more and more complicated, because I realized that anything that happens in reality defies the logic of how you would block it in visual fiction. Even with something that happens in a simple, given space, like a convenience store, the way people move and what they do is very surprising. If you were to shoot a basic interaction between two people in a convenience store with your phone and then watch it a couple of times, you’d realize the blocking of reality is quite unexpected. People might enter and exit before they even do anything! Odd things happen all the time. If you can capture those moments and use them in your fiction, you can represent reality in an almost spooky way. I remember Frank Capra talking about directing his extras on the street for Meet John Doe or something. He’d give each of them a story, like, “You’re looking for an address,” or “You’re talking about what you’re having for dinner as you’re walking down the street.” He tried to give them specific directions to make the scene come alive.

To what extent has your career been driven by the desire to experiment with form?

A lot. I think just the idea of a given form is enticing. Where it came from and where it went in somebody’s career — that’s always interesting to think about. Emulating different forms to show different things has always been something to work on, like having a recipe to make. I like having the technical side of a production be involved in the planning of a given film in the same way costumes would be. We’d be starting fresh again, and the camera could have as much personality as, say, the set design, or the actors and the clothes they’re wearing.

There’s a tremendous difference between your Drugstore Cowboy and My Own Private Idaho era, where you’re doing more traditional narrative filmmaking, and the period where you directed Gerry and Elephant and Last Days, which are defined by long takes with a flowing Steadicam.

Elephant and Gerry were influenced a lot by Eastern European filmmakers: Andrei Tarkovsky but also Béla Tarr. There were things Béla Tarr would do that I was trying to conform to. He wasn’t intercutting at all. He’d do single shots that would move, or move and then stop and then move again. His shot list would be a single shot. When I saw Bela’s films for the first time, it seemed like — at least in that period of time in the mid-’90s when he was making Sátántangó — he had found a way outside of modern cinema, which had learned about closeups and medium shots and long shots and how to gather those shots and put them all together through a process which started to be developed around 1910. I mean, the audience had to be taught these ways of making cinema that originated in the silent era. You know how silent filmmakers would use a vignette for a close-up, like this? [Curves his hands around his face to approximate an iris matte.] That was so the audience would know, Oh, this is a special shot. It’s not like they don’t have legs!

Those vignettes looked like portraits of the time.

Like the portraits they might have had at home on their walls. The processes filmmakers had arrived at in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s were basically refined versions of this mosaic method you would employ in order to facilitate the emotion of the scenes: The editor would use all those different shots to make the scene happen in a way it had never happened on set. When you get rid of all of that and do it in just one shot, it brings the action into a whole different arena that somehow relates to theater, while also creating an alternative cinematic reality from what people are used to.

It’s interesting that the film that got you out of “mosaic” filmmaking and into films that were made of long, unbroken shots was Psycho in 1998. You remade what is probably the most famous film by Alfred Hitchcock, a director you’ve told me you tried to emulate at the start of your career. I have to ask: What on Earth motivated you to not only remake Psycho, but do it, not exactly shot-for-shot, but close to it?

It’s as close as we could get. The shots were even supposed to be the same length, but in the end, when we cut it together, it seemed like the shots needed to be different lengths and have different rhythms. Psycho was another cinematic experiment.

What was the point of it?

To see what would happen.

What kind of itch did it scratch?

Psycho was a reaction to the way Hollywood was getting into remakes in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Even today, storytelling-wise, it’s easier to use characters the audience already know so you don’t have to try to make audiences understand them in the first 30 minutes of the movie. Instead, you have Batman, and the audience is like, We know Batman. We know his history. We can get on with the story. With an original story, you have a length of time where a viewer is supposed to get to know who the people are. Industrial cinema has always tried to figure out how to get rid of that first part because they don’t want to have to get to know people. Remakes became a way to do that. Later, comic-book movies became another way.

I was taking it to the next step: If you’re going to take a thing and rob it, why not just go ahead and take the whole thing? Why even leave out the angles the director and the DP worked out? The more I thought about it, the more it became a question: What would happen if I actually did this? It was only after the success of Good Will Hunting that I had the clout to have them think a movie like that was a good idea.

Had you pitched a shot-for-shot remake of Psycho before that point in your career?

Yes. I would continue to bring it up every now and then and they would tell me it was a bad idea. Then suddenly, one day, they said, “Yes! Let’s do this!” And I asked myself: Do I really want to do this? And I did!

Was part of the mental calculus, I’m never going to have another chance like this again, so I might as well take it?

Yes! [Laughs.] What was in it for me was the chance to see what would happen. The film I chose to remake was one I knew very well. It was a good example of how much different a remake can be from the original, even if you’re copying. With Psycho, I wasn’t working in my medium, I was working in Hitchcock’s medium. All the things I don’t have that he had, like the paranoia he used to talk about all the time in interviews, and his Catholicism — these things inside his film all of a sudden weren’t there anymore.

We were doing the same kind of thing on the third episode of Feud but with the films of the Maysles Brothers and D.A. Pennebaker. We were trying to approximate a documentary of the Black and White Ball so we could see what it would have been like to capture the black-and-white ball, as opposed to explaining it cinematically. It was an experiment. We were emulating films that existed. Their chaos was inspirational.

More From This Series

- Even Tom Hollander Felt Pressure Holding Court for the Swans

- Feud’s Chloë Sevigny Wants Hollywood to Read More Books

- Feud: Capote vs. the Swans Series-Finale Recap: Epilogue