Spoilers ahead for Midnight Mass.

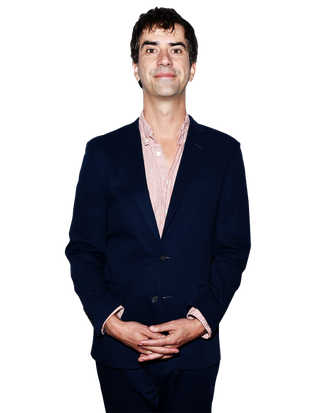

Hamish Linklater has been doing reliably strong work in movies and television for more than two decades. You’ve seen him in supporting roles in The Big Short, The New Adventures of Old Christine, The Newsroom, Fargo, and Legion, among other things. But in Midnight Mass, the latest Netflix work of dramatic horror from creator Mike Flanagan, Linklater commands the pulpit as Father Paul, the new pastor in the small town of Crockett Island who brings, um, new blood into the congregation.

It was a meaty role for the actor, filled with lengthy monologues often shot in a single take. And it clearly had an impact on Linklater; while discussing the show’s gory, emotional Easter Sunday finale sequence during a Zoom call from his car — he had just dropped off his oldest daughter at high school — he got a bit choked up about a plot point involving a parent and child in the series. Here’s an edited and condensed version of that conversation.

I really was blown away by your work in Midnight Mass. Did you audition for this?

Totally auditioned for it. It was a lot of pages and a lot of sermons. It was like 14 pages and a lot of it was monologue, and I had a very short turnaround. I remember I got the material three days before I was going to go in. This is back in the days of actual physical auditions instead of just self-taping.

So this was pre-pandemic?

Yeah, totally. I had nine pages of sides and they gave me five more the day before, which was so delightful. It was just a joy to do it and to learn it. The lines went in like water, which was very lucky. They sent me the first three episodes so I knew some of what was coming, but not the rest. That came later.

I read that you are not necessarily a horror fan. Even more than some of Mike Flanagan’s other shows and movies, this felt like a drama first and a work of horror second. Was that part of the appeal for you?

I really was such a big fan of The Haunting of Hill House because I’m [so] not a fan of horror. I get too frightened by horror, but I found his work in that show unsettled me. Unsettled me. Properly. I was watching for the deep unsettling [nature] of the thing, not just for the jump-out scares. Then this material, when I got those first three episodes [of Midnight Mass], I was like, oh well, I don’t have to worry about being scary or doing any of the horror trope acting, and can just play this guy who really feels like he has a good message to spread. Unfortunately, it wasn’t so good.

As you said, you have a lot of meaty monologues in this series, especially the Good Friday sermon, which may be the longest one. How do you prepare for a scene like that? There’s the memorization part, obviously, but then trying to hit all the notes you want to hit in such a long speech is a challenge, too.

There were some script changes during the shutdown. The island was more populated in the version we read in March than the version [we shot], which was partly a pandemic consideration but turned out to be wonderful for the story: that the population was 127 on the island instead of 1,000. Those speeches stayed the same, so I worked on them for the audition. I worked on them for the table read. Then I drilled them like crazy because the bonus of doing TV is you can cut and go back, but it’s also very embarrassing when you have 100 wonderful background artists and your fellow cast sitting there. You do feel bad if you don’t know your lines, and their job is to just sit and listen for that long. I was certainly nervous about that and I wanted to have them down. Especially that Good Friday one, because the original plan [Father Paul] comes back to the island with has taken a turn and he’s going to different parts of scripture to make sense of where he is in the story, what’s happening in the story and what his mission is.

He’s doing very active reading of the scripture and digestion of scripture in order to make this new outcome occur. He’s got to galvanize that parish. He’s galvanizing himself at the same time. When you do a monologue, if you know what the end is, it’s kind of like, no point in acting it. A sermon is a long argument. It is a long essay, but I think for a congregation to be engaged in a sermon effectively, the argument should be discovered on its feet, or the impression should be that the argument is being discovered on its feet, and that the conclusion is the inevitable conclusion.

I think you succeeded. It felt to me that your character was discovering his words as he’s speaking. Was your goal to try to do that in one take?

Mike hates doing ADR. I think in one of the four main speeches there are sections maybe that are taken from two takes, but certainly three of them are one take all the way through. We would do the whole thing all the way through, but the cadence would be different, the tone would be different, from one to the other. So what you hear is whichever one he liked.

My takeaway, especially from that Good Friday sermon, was that Midnight Mass was commenting on Evangelical Christianity. Some of the lines — “What is otherwise horrible is good because of where it’s headed”; “You don’t fight for a country. You fight for God’s kingdom.” — really made me think about the religious right. Was that something you and Mike talked about or you had in your mind when you were formulating the character?

In performance, no, because I think at the start of the story the means to achieve his ends seem a lot easier and lovelier. As the story goes on, he discovers that the means to achieve his ends are a lot scarier and gnarlier than he had anticipated. But he is really committed to the end, which is no more death. He thinks it is written in the Bible that that is actually what God’s ends are and this is where we are finally at [in] this stage in human evolution. So I just have to think about that as a positive thing, otherwise I’m sort of twisting my mustache. Or I’m judging the character, and then he becomes two-dimensional and then I, Hamish, won’t play him as well. But certainly I, Hamish, when I don’t have the job of trying to play my character well, totally get the parallels to our current moment that Mike has so beautifully drawn and created with that island.

As a critic I’m always seeing things in a way that is maybe not as helpful for actors, because broader subtext probably doesn’t help you at all in your performance, right?

If you’re hearing the mood music, if you’re playing the mood music in your acting, then what are you watching? There’s no point to it. You’ve got to be playing your part of the orchestra and then you’re going to have the music. Definitely I’ve got to come up with the subtext, which is not my Hamish political subtext for what I’m playing. I’ve got to come up with the subtext that is going to be useful for keeping my flute in tempo.

On Easter Sunday at the end of the series, things get, as you said, pretty gnarly. There’s a point at which Father Paul realizes, Oh, this is bad. This is not what I wanted. What wakes him up?

The love of his life shoots him in the head. She’s his wake-up call and he sees it happening. I think the plan was to lock the doors and keep everybody in while this sort of transformative period takes place within the parish, but not to let people, when they’re in this hungry state, out of the church.

Then once it has spread, he’s like, “Everyone can come into the church. Everyone stay safe here from the sun.” But when I was reading the … I can’t even talk about it, it’s so silly. [Linklater tears up.] I do cry a lot in my life but I don’t actually cry easily as an actor. But when I, Hamish, was reading these scripts and I got to that part with the Sheriff and his son, I was like, oh my God, of course, inevitably, it has to come to this point of what this series has to do. It’s telling this story. That’s real horror — the son rejecting his father’s faith.

Was that a difficult scene to play?

There were so many working parts in that. There were so many stunts. There were all these people prepared to shoot this massive orgy of violence, and they had spent so much time planning it out, storyboarding everything. It was just like, we’ve got to keep it moving. That was certainly more of a technical period.

Just the idea of blocking that scene gave me a headache.

Tthey spent months and months blocking what took four days, I think, to shoot.

After doing this, would you consider doing something in the horror genre again?

Oh, I want to do everything. Woe betide an actor who thinks he can plan his or her career. I mean, certainly a great rule of thumb is always to chase good writing. I’ll always be doing that. And to work with good directors. I’ll always want to do that. I think the genre will follow. I just got to do my first Western. It was so complicated to plan, but it was this great director, Walter Hill. I think he’s 79 or just turning 80. Just this massive, wonderful guy, wonderful actors in it, but it was a Western. You make decisions on what you’re going to chase and run after based on a million different factors. This one was, I got to wear a mustache and a cowboy hat. I never thought I’d see the day.

Again, this might be outside your wheelhouse as the actor, but the connections between the pandemic and what’s going on in Midnight Mass were interesting to me. There’s the whole business with Annabeth Gish’s character saying, “Maybe this is a medical issue and maybe there’s something that’s spreading.” I was also recently listening to a podcast about the vampire panics in New England back in the 1600s, and so much of that is tied directly to the consumption and so many people dying. Their explanation was vampires. I don’t know if Mike was tapping into that idea in a way, but it was really interesting to see the connection between those two things.

There’s also the craving and the addiction. There’s something unsettling in the sensuality of the vampire myth, and I think that’s why it won’t go away. It’s a way that those natural human cravings get tabooed up into wonderful myths. I think that’s why it makes so much sense to Father Paul that this [vampire] would be an angel, because the experience of the encounter, the ravishment of the angel, is so all-consuming and feels like a religious experience. That’s why people call it the work of the devil, you know — that level of ravishment.

The way the angel, or whatever you want to call it, would sort of cradle the heads of the people as he’s feeding — there’s something almost tender about it, even though obviously it was very violent and horrible.

Yeah, I think that’s why horror is one of America’s religions. It has a language for talking about those deep, primal human needs that religion also addresses with its commandments and strictures. Yeah, jazz and horror: That’s what we got for you.

I assume the angel was an actual actor? None of that was CGI?

It’s an actual wonderful actor named Quinton Boisclair. This is my second time working with him, actually, in Vancouver. On Legion, in the first season, there’s this enormous, horrifying creature that’s like the main bad element in Legion. Same actor. He’s like this 900-pound blob on Legion and a 90-pound terror in Midnight Mass. He’s really sweet and super impressive. Very slender, very tall dude, who had to stand out in the freezing cold weather with just a thin layer of prosthesis over his naked body while we were shooting late nights there. He’s a total hero. Mike would prefer to go practical instead of CGI whenever he can. I didn’t have to act my terror. That guy really attacked me.

Obviously you’re acting, but just the sight of that guy in costume must have been pretty creepy.

Yeah, yeah. And then as soon as they say “Cut,” he’s like, “How are you doing? How was that for you? Okay, that’s good.” Then everyone’s back on their Instagram, so it feels safe.