There are two types of sequel writers: those who’ve earned the opportunity to build on their previous work and those who are hired to take existing characters or worlds and do something new with them. While no two sequel jobs are the same, all are filled with myriad pressures and expectations from fans who want to relive their experience with the first movie and studios who want a financial, if not critical, repeat of their hit. Audiences, in particular, are a tough lot for the screenwriter to please. Take too many big creative swings and you risk tainting, if not outright eliminating, whatever made the previous movie special for fans. Take too few chances and you’re viewed as a boring, uncreative, cash-grabbing hack. To get a better sense of just how difficult it is to pen a sequel, Vulture spoke to 11 screenwriters who’ve worked across multiple sequel genres with varying success.

.

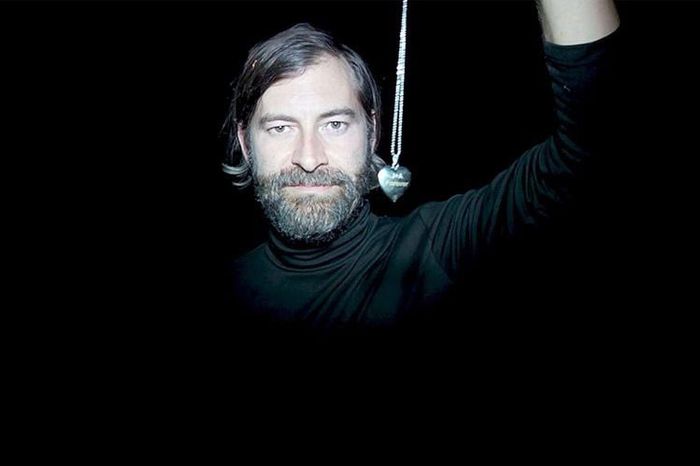

Michael Green, Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

I’ve played in a lot of sandboxes, and Blade Runner 2049 was the one where I heard “Don’t fuck it up” more than any other time. My own father, when I told him I got the job, said, “Wow, that’s a big one. You can’t fuck that up.”

I had an advantage in that I was developing it with and for Ridley Scott. He gave me permission, by virtue of liking the idea, to see it through. I said to myself, Okay, I’ll hit it as hard as I can, and if they don’t like it, they can always hire someone else. I felt the mistake would be to subvert any of my intentions out of fear of it being rejected. Don’t bleed before you’re cut, as the expression goes.

After the original Blade Runner, there were certainly stories told and suggested about the further adventures of Rick Deckard, but I was interested in doing something about someone else, where Rick Deckard wasn’t the character to follow but rather the object sought after. If you’re tackling something that’s considered a sequel, you get to ask yourself, How am I widening the circle? What epochal moment in this world or this set of characters do I get to tell? More crassly, you get to ask yourself, What story can I tell that is the full and complete story and not a mere episode? At the end of the day, it is all fanfiction.

The hardest part is knowing that the most passionate, crazy superfans of whatever you’re expanding will never, no matter what you do, accept your addition as worthy. The thing is, the rabid fans are going to show up to be disappointed. You can’t write for them because they cannot be made happy, sort of like The Simpsons’ Comic Book Guy.

.

Daniel Waters, Batman Returns (1992)

Someone else can look at Batman Returns and have a lot to pick apart. I was the main writer on the film and the only credited screenplay writer, though they did have another writer come in and kind of streamline it. The word they use is normalize. I was definitely more involved with the characters, but there are these plot elements of the first-born children of Gotham City that I had nothing to do with. I was like, What the fuck is this shit? Then I realized, Well, I didn’t have much of a plot for Batman Returns. It really was kind of this strange film of strange people interacting in a city, and I didn’t concern myself with the A to B of it.

I wasn’t even given directives by Tim Burton — just that he didn’t want Batman Returns to have anything to do with the first Batman. To be honest, I’m not a fan of Tim Burton’s first Batman. We didn’t have any loyalty to past histories of the Catwoman or Penguin character either. We did absolutely our own thing. In my first draft, Danny DeVito’s complaint about Penguin was, “This is too much like a Danny DeVito character.”

With Batman, I gave him all these speeches about how Gotham City doesn’t deserve protection; he’s really kind of bitter and cynical. Michael Keaton looks at the script and goes, “When Bruce Wayne is Batman, he shouldn’t be having long speeches.” So I cut them. Then when I finally saw Christopher Nolan’s Batman, he did not play by that rule. When Christian Bale is wearing the Batman suit, he’s giving these long speeches. “I am the darkness in the light.” You’re just expecting Christian Bale to pull out a Fiji and take a sip because he’s having to keep up the voice for so long.

I think now — especially since the 2022 Batman came out, which I quite enjoyed — people are coming around to Batman Returns. Not that it wasn’t respected when it came out, but it’s never been popular with true Batman fans. A friend, fellow screenwriter Josh Olson, who wrote A History of Violence, has a line: “Batman Returns is a movie for people who hate Batman.” I accept that criticism.

.

Mark Bomback, Live Free or Die Hard (2007)

I’ve never been the person who wrote the original film. I’m always stepping into a franchise once a film has established a fanbase. When I think about the sequel I’ve worked on that provoked the most anxiety, it probably was Live Free or Die Hard, mostly because I was very inexperienced at the time. It was a huge opportunity for me, and I had this knot in my stomach the entire time, feeling that at any point I was going to get fired.

The biggest challenge was getting the voice for John McClane right. I’m not one of these writers who reads their work out loud in their office, but this was one time where I had to do my best Bruce Willis impersonation while writing. Probably the biggest point of pride was when I turned the script into the studio and they said, “Oh, this reads like a Die Hard movie,” even though that first draft probably at best only halfway resembles the finished film.

What was doubly challenging on that film was that Bruce was also a producer and had so much invested in the character. It was very hard to speak with authority to him about what I thought was best for the story. He had this great line that he used to use a lot: Whenever there was any kind of argument, whether it was with the script or the director or the studio, it was, “Who’s your second choice to play John McClane?” And that’s a very good trump card to play when you’re trying to figure stuff out.

I had given Bruce some dialogue, and he just left a voicemail saying, “I don’t want to see any more exclamation points in my dialogue. I’ll decide whether to put exclamation points in my work.” But, you know, he trusted me in a way that, when I look back, I actually can’t believe. I had one produced credit, and that film was not particularly good. I had done some rewriting for him on another film, which is why I think he felt a certain amount of comfort and treated me like a collaborator in a way that was really thrilling.

.

Brannon Braga, Star Trek: Generations (1994)

Star Trek: Generations was the seventh Star Trek movie and a sequel to a TV show. Ron Moore and I wrote it, and it was incredibly challenging because we’d never written a movie before.

We were servicing a lot of things: two captains, the fans, ourselves, the studio. We were getting notes from Patrick Stewart, from William Shatner. Shatner wanted to make sure that he had enough action and that the emotional journey made sense. And then Stewart, he wanted something he could really sink his teeth into — worthy of the big screen.

Kirk’s death was originally somewhat unceremonious. We tested the movie, and the audience didn’t respond to the ending at all. They hated it. It felt anticlimactic once we saw it cut together, but it really wasn’t until we showed it to an audience that we got confirmation that we needed to rewrite and reshoot an ending that was much more spectacular. I can’t remember how many days it took to reshoot or how much it cost, but it was quite substantial. I’ll say this: Shatner’s character was getting a sendoff, and if he wasn’t happy with it, we would have known about it.

You’re always, in the back of your mind, thinking about the fans. With Star Trek, you realize there’s just no satisfying everybody. The movie did really well. It was No. 1 at the box office when it opened. It got some positive reviews, it got some negative reviews, it received some valid criticisms. We took the lessons we learned from that to make a better sequel, First Contact, with a better villain, higher stakes, and just a higher concept. And we had the benefit of only dealing with one captain.

.

Derek Kolstad, John Wick: Chapter 2 (2017)

Of course, when the first John Wick did well, it was like, Okay, let’s do a sequel now. But when you’re green-lit to do it, suddenly you have a lot more people in the kitchen, and you have a lot of conflicting ideas. And once you’re into production, it’s, Oh, shit. We’ve got to not only do this again, but we’ve got to do it as well, if not better.

It was a gun that we put to all of our heads. As a fan of the medium of sequels, you know that the second installment is the most important to be the foundation of the franchise. It was hard to know where to focus. We love the character, and ultimately, when it comes down to it, we love Keanu. I mean, his passion for that character, the training he did, and the amount of time and effort he put into that role — you want to do right by him. To be honest, I don’t want to repeat that kind of production again because it burned us all out.

The biggest thing for me was making sure that a sequel is an extension of the first story and not a remake of it. We planted seeds with the various characters, especially at the Continental, who could come back to grow to harvest. That’s kind of the way we figured it, and we liked the idea of it becoming that quilt work. You want to deviate a little bit from your lead in the sequels to get a 3 percent perspective shift on the world so it feels bigger. Then when you return to your lead, it’s like, Oh, fuck yeah, John Wick!

A lot of the work was done in the rewrite and in the edit, just trying to figure out what was the cleanest way from here to there. For as “simple” a story this was, it was labyrinthian in regards to the various pathways we took it, the various layers of that world we peeled off and then stapled back into place for other iterations. The one thing that was a blessing, as we all realized, was that you get vengeance once and you get justice as many times as you want.

.

Reid Carolin, Magic Mike XXL (2015)

The first challenge was separating Magic Mike XXL in tone from the first movie. Where the first movie was kind of this serious exposé of the darker aspects of the world of stripping that Channing actually lived in Tampa, with the second movie, we wanted to make it more of a fantasy — about the lighter side of dancing and the aspects of that world we and Channing loved. And we wanted to make it like a road comedy.

I was in the middle of writing the script, and we had this kind of lame “car breaks down” sequence. We couldn’t get excited about it. I flew up to Vancouver, where Channing was at the time. I was just like, “It all feels too generic. What were these things like? What happened to you when you went to these stripper conventions?” He was like, “Dude, it was dumb. We’d all just get in the back of these U-Hauls, and we’d just do ecstasy and sit there and roll our faces off and talk, and then we’d go dance.” And I was like, Oh my God. That’s the scene. They all do ecstasy and they’re all rolling their faces off, and then they stop at some mini-mart, and they challenge each other to make a woman happy with a dance. That was the moment where it became real and kind of strange and outside of the bounds of normal screenwriting. That was when I fell in love with the movie.

But I think the real juicy obstacle that we faced along the way was we had actually cast and prepped the movie with Jamie Foxx in mind for this central role of the club owner named Rome. And Jamie ended up not being able to do it pretty close to shooting. Then one day it was like, What if it’s a woman? And that epiphany set off a whole string of ideas. Well, what if it’s Jada Pinkett Smith? Would she do it? We sort of cast Jada sight unseen. She just looked at a script written for a guy and was like, “I trust you. I’ll do it.” We rewrote it for her by the time she showed up on set, and she just went with it. It transformed the energy of the movie.

.

Patrick Brice, Creep 2 (2017)

We didn’t want this movie to just be a sequel for the sake of sequels. We wanted it to be something where we could further indulge a lot of the themes and goofier elements of the first movie.

There’s a meta element. Desiree Akhavan is playing this video artist who’s at a point of creative block in her life. She doesn’t know what to do next, and that was definitely reflective of where I was at the time. That came from Mark Duplass and I banging our heads against the wall. With the Creep movies, and with horror films in general, you’re always having to answer that question of, Why is this person still there? Why is this person putting themselves in harm’s way? We really needed to give the person who was going to be the protagonist in Creep 2 a reason to be with Mark’s character, and making the character a video artist gave her a need to be there that was personal and selfish but still believable. Landing on this idea was a big aha moment for us.

Another thing that was truly inspiring for Mark and me was the realization that, because of how we ended the first movie, we created this mysterious character who could pop up anywhere. I always referred to him as Zelig if he was a serial killer. He’s a pathological liar. You don’t know what his real name is at any given time. But you know now he’s a serial killer. That’s the other thing we had to solve with this second movie: The tension of the first film relied on the fact that the audience didn’t know whether this guy was actually capable of killing people or not. With the second film, we had to create another level of tension. We leaned on this character playing this game of trust.

My heart sinks at the 70-minute mark of the movie, when Mark’s character has Desiree’s character out in the woods. It’s a much darker, more sinister moment than the death in the first movie, and part of it is because you’ve sort of been charmed by this person. That was a decision made out of instinct. I didn’t know it was going to feel that way, but the moment we watched the first rough cut, it was like, Oh, yeah, this is now doing something that is building on the strengths of the first movie and entering a new realm.

.

Kent Osborne, Uncle Kent 2 (2015)

When Uncle Kent came out, my friends were like, “Oh, it’s you. I’m watching a movie about you.” So for the next three years or so, if I was hanging out telling a funny story, everyone would be like, “Uncle Kent 2!” Then I started thinking about doing this epic postapocalyptic movie. It would have picked up where the first movie ended. It’d be the apocalypse, and I’m going to leave my house because I have to get cat food because my cat won’t eat the food in the apocalypse rations. I was in Austin having dinner with Andrew Bujalski, and I was telling him about the idea that was still at this point just a joke. He wrote me an email a couple days later, and he said, “Look, I don’t want to direct it, but you have to make this movie.” So I kept trying to flesh it out.

Then my cat died in real life, so I was like, Well, now this movie doesn’t work. I kind of forgot about it until I ran into some producer friends. They were interested in me making a sequel, and so I started thinking about it again. But I couldn’t use that original idea because it would have been too expensive. I was taking a ferry up the Inside Passage to Alaska, and I was camping on the deck of the boat with all these other people. One night, we smoked it. I was staring at the water and thinking about if I fell, that would be the last anyone heard from me. I crawled back to my tent, and I was so high I couldn’t sleep. This song was in my head, and it was driving me crazy, and I was like, I’m just gonna write. I’ll write until I stop being high. I was having a hard time thinking of what this low-budget sequel would be, and then when I had this earworm in my head and I was kind of high, I thought, Oh, that’s what the movie is about.

The tagline was, “You didn’t have to see the first one,” because you really don’t. I did want to have little things in there for people who saw the first one to be entertained, but that was the goal: Someone who’s never seen the first movie and doesn’t know who I am or Joe Swanberg is could watch it and be like, Oh, I get it. This guy’s friend made a movie about him, and now he’s trying to make a second movie.

.

Larry Gross, Another 48 Hrs. (1990)

The obvious issue with the movie was that we were going into production eight years after the first film, which, in today’s production culture, is an insanely long time. In that intervening period, Eddie Murphy had earned a couple of billion dollars at the box office, and he had gone from being a first-time actor teenager, who was unknown and unheralded as a movie lead, to being one of, if not the, biggest box-office names in the world. I mean, it’s worth pointing out that he earned more salary on the second film than the whole first film costs.

It was a reason to make the film as well as the difficulty with the film. We had to service the institution that Eddie had become. But I felt that we came up with a fun way to redo the country-western bar scene from the original. I had a pretty big hand in conceiving that in the first film. There was a very, very spirited, volatile, and passionately held argument between different factions of studio executives and producers and us about Eddie’s behavior being too extreme in the scene. This was the team that had made The Warriors and had seen violence in response to their movies, which, you know, killed the commercial prospects of the film. There was a real strenuous set of voices saying, “Let’s trim Eddie down in that scene and make him less extreme,” and I happened to make the argument that if we cut it down, by making it veer on realism, we’d be more likely to provoke that kind of violence.

The very first audience that saw it wasn’t quite sure how to react, but they ultimately found the movie funny. Then gradually the word of mouth that the movie was funny spread and everyone knew what to expect from the scene when they saw it and responded accordingly.

.

Joe Berlinger, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000)

I should have known something was amiss by how I actually came to be the director of this movie. A young executive at Artisan, the short-lived studio, who was a huge fan of Paradise Lost, reached out to me to see if I had any interest in features. I said, “I have this really cool project I’m developing called The Little Fellow in the Attic,” which is a film I still want to make. It’s a true story about a guy who lived in the attic of his lover, unbeknownst to her husband, for 20 years. She loved the idea, and I kept meeting higher and higher levels of executives. Finally, I’m sitting with the three guys who were running Artisan. I start my pitch, and before I could even finish the first sentence, Amir Malin, the president, held up his hand and said, “You’re not here for that movie. We actually want to talk to you about the sequel to The Blair Witch Project.”

I had a difficult relationship with Blair Witch. As a documentarian, I had a problem with the idea that shaking the camera equates to reality, and this movie was sold to the American public in the early days of the internet like it was real. The Artisan guys said, “Well, here are three different scripts for a movie. Why don’t you take them home?” All three of them were continuations of the found-footage technique. I called them up and said, “I appreciate you giving me the scripts, but I don’t think you can do this anymore.” So they said, “Well, what would you do?” I said, “Let’s not do a sequel to the underlying story. I, as a documentarian, observed this fascination of how this film became this cultural phenomenon. Even after the movie came out, fans went down to Burkittsville in droves because they were convinced that the witch is real. Let’s make a sequel that talks about that phenomenon.” They bought it, much to my surprise.

The funny thing about it is I basically had no oversight on set. I kept sending dailies to L.A. and they kept emailing me back, saying, “Keep up the good work.” I handed in my final cut, and I get this phone call from a marketing executive: “We’ve tested the movie, and we need more scares.” They ordered a bunch of reshoots and changed the structure of the film. My film didn’t have any of the bloody reenactments. The final reveal was supposed to be this ten-minute scene in which you finally realize that there is no Blair Witch and that the kids were the killers. Artisan took that scene, broke it up, and sprinkled it throughout the movie. They gave Jeffrey Donovan this big backstory with a straightjacket like he came from a mental institution. None of it made any sense to me.

I was director in name, but I had lost control. My agent, who’s no longer my agent, said, “If you step away, you’ll never get another opportunity to make a movie.” I just gulped and went along with the changes. It was a very painful experience. There’s a happy ending to the story, though. When the movie came out, it put me into a profound funk. Literally, for months, I curled up in a ball of depression. I remember my wife came into my office and said, “Come on, snap out of it. Watch Paradise Lost and remind yourself you’re a good filmmaker.” So I popped on Paradise Lost, and the opening title sequence is to a Metallica track called “Welcome Home (Sanitarium).” That was the start of 2004’s Some Kind of Monster. That was one of the greatest adventures I’ve ever had in my life, and that film definitely would not have happened had I not had a massive belly flop with Blair Witch 2.

.

Simon Barrett, Blair Witch (2016)

The challenges of Blair Witch were less creative and more to do with the fact that just no one actually wanted it, and we were constantly trying to find a way to convince them to do so. We were following up a sequel that had gone in a completely opposite direction. Ultimately, I feel like the only mistake director Adam Wingard and I really made is that we didn’t go strange or original enough. We tried to closely adhere to the existing mythology and what we and the studio kind of agreed the hypothetical fan might want. When you’re second-guessing the desires of a viewer, you’re frequently on the wrong track.

We knew that Lionsgate was going to give us a lot of creative freedom. But we were also in a phase where we were coming off The Guest, which wasn’t that well received at Sundance, and You’re Next had just flopped. So we were like, We want to try to make this more mainstream. It would be very easy for me to say, “The studio told us to do it this way, and we would have done it better.” But that’s completely untrue. We had a very copacetic relationship with the studio, and they were happy with the movie, and we were very happy with the movie right up until the point that all the critics hated it.

I’m not interested in relitigating the tepid response to a sequel that has been, justifiably, mostly forgotten. The truth is, we’re talking about like a $6 million movie here, so it was profitable. It just didn’t do what we hoped it would on a critical and fan level. I’m still very proud of it. If you didn’t get motion sick enough that you were able to make it to the ending, pretty much everyone agrees that the last 30 minutes are quite scary. We set out to make a scary film. Most people didn’t see it, and that’s fine.

That’s how you have to keep going with your career as a creative person — just keep trying to not repeat yourself and make things you think are good. And when you get it wrong, try to learn the lessons and move on. In my case, I haven’t written any more horror sequels; let’s put it that way.

More From This Series

- The 102 Best Movie Sequels of All Time

- Who Is the Greatest Character to Come Out of a Sequel?

- Hollywood Can’t Leave Romancing the Stone Alone