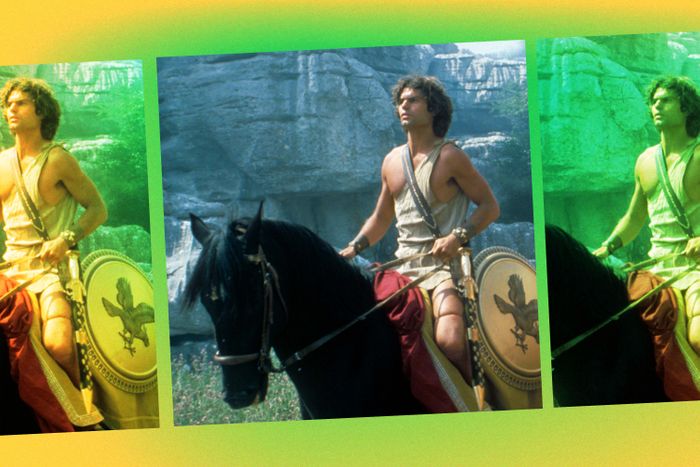

Given the state of Hollywood today, it seems all but inevitable that, at some point, every respected actor is going to take a role in the Marvel Cinematic Universe or another, similarly gargantuan blockbuster franchise. But back in the 1980s, it was much more notable when a major, more “serious” actor appeared in a genre popcorn flick. Clash of the Titans, a retelling of the ancient Greek myth of Perseus and Medusa, was just such a movie. While legendary stop-motion special-effects artist Ray Harryhausen’s mythical monsters proved a box-office draw, the gods themselves were portrayed by a pantheon of great actors, like Maggie Smith, Claire Bloom, and Laurence Olivier. It was Olivier, playing Zeus, who got a young, classically trained actor named Harry Hamlin interested in a fantastical “toga movie.”

In the spring of 1979, Hamlin, who at that point had only appeared in the throwback double-feature Movie Movie the previous year, was in talks to star in a film version of Tristan and Isolde with Kate Mulgrew and Richard Burton. Then he got the call from MGM about an opportunity to co-star with Olivier.

“I went, ‘Wait a minute. Richard Burton … Laurence Olivier. Who wins this battle?’” Hamlin remembers. He took the meeting with MGM, and they thought he looked the part of a half-divine hero of myth. They cast him on the spot. “I walked into the room and they were taking Polaroids of me, and I walked out of the room and they were sending me down to wardrobe for fittings. I don’t even know if I read for it.”

Hamlin didn’t end up sharing the screen with Olivier (the gods kept to Mt. Olympus, a separate set, though Oliver insisted on being onstage for a scene where Zeus communicated with Perseus through a magical shield, rather than just doing it via a postproduction bit of recording.) Still, the two actors formed a friendship, one that led to Olivier — the legendary actor best known for playing Hamlet, King Henry the Fifth, and a role in Spartacus — eventually apologizing for being in the magical monster movie, which at that point wasn’t the cult classic it is now.

“In a letter, he said, ‘Sorry to have met you under these circumstances, but I have so many mouths to feed,’” Hamlin remembers. “He was basically apologizing for being in the movie that I was the star of, which I thought was kind of funny.”

Hamlin would go on to have a successful career, though not the one he envisioned when he first started. He later starred in L.A. Law (which helped him get voted People’s Sexiest Man Alive in 1987) and landed memorable roles in Veronica Mars and Mad Men, and he’ll soon be seen playing Tom Brokaw in the second season of National Geographic’s The Hot Zone, a dramatization of the post-9/11 anthrax attacks. Before all that, though, he defeated Medusa and the mighty Kraken as Perseus — although it turns out there were many, many other battles to be fought on the set of Clash of the Titans, which turns 40 this week.

So Clash of the Titans opened in second place to Raiders of the Lost Ark, which is respectable.

It might have opened in first were it not for my insistence that I not participate in a worldwide press tour. The producers never spoke to me again after that. Ray Harryhausen wouldn’t talk to me for 25 years after that. They came to me and said they wanted to do this global press tour. I was really excited. They had all the countries we were going to, but the big kickoff party was going to be in Johannesburg. I said, “The one place I can’t go of all those places is Johannesburg because I’m on an anti-apartheid committee.” And they said, “What’s apartheid?” I said, “Well, you’ll have to look it up, but I can’t go.” And they said, “Well, that’s a problem because Johannesburg is underwriting the entire tour.” They were not happy with me. They thought we could have been much more competitive with Raiders of the Lost Ark if we had done that tour.

You say Laurence Olivier was one of the reasons you took the role, but you don’t really share the screen with him much. Did you feel like you missed out?

No, I just wanted to meet him. I sort of wanted to style my career after his. Having been classically trained for years, that was my journey — only classical theater. I had no interest in doing movies, whatsoever, and then I got cast in Movie Movie. My mother made me do that. I had a Fulbright scholarship to study Shakespeare in London, and I had to blow that off in order to do the movie. But I’m fine with that. It gave me a great career.

But Clash … the script was terrible. I did it because Laurence Olivier and Maggie Smith were in it and I thought maybe there would be some way to dust up the script a little bit and make it better. And we did work on it. Every day with the director we worked on the dialogue, of which there was very little. But I did the best I could to elevate a pretty dreadful script. I think it worked. How many actors have done toga movies, and then how many actors have done toga movies that had legs that went on for 20, 30 years — or, in this case, 40 years? Most actors, you can’t remember their toga movies, but something was right with this movie. The story worked, the love story worked, the casting worked, having all those big players who were classically trained megastars. I think all those things came together and made it work.

Were you afraid it wouldn’t work?

At one point they wanted me to do something that would have definitely killed the movie had I done what they wanted me to do. I actually quit the movie when they told me they wanted me to do this thing. That also really pissed them off because they had an impetuous actor on their hands. They didn’t want me to cut Medusa’s head off with a sword. They said, “You can’t cut her head off with a sword because we got a telex from London that said they’d determined that if you cut her head off with a sword, it would get an X-rating for violence for England, and we would lose this gigantic audience of preteens.” And I said, “Well, how does her head come off? Because I’ve got to be able to take it and hold it up to the Kraken?” And they said, “We’ve devised this method whereby you’re going to toss your shield like a Frisbee and it’s going to bounce off a wall and inadvertently cut her head off.” At which point I locked myself in my trailer.

They unplugged all the electricity to the trailer. This was obviously before cell phones, and we were shooting somewhere in the middle of a forest in Malta. They had to drive to Valletta to find a payphone to call London. I was locked in the trailer for a good seven hours, knowing that they were going to have to let me out at some point, and that’s when I would fly back to L.A. They kept sending in people to try to change my mind all day. And, every time they left, they were on my side.

At the end of the day, they had to relent. They let me cut her head off with a sword.

What was it like to film those scenes where you’re swinging a sword at a giant scorpion who wasn’t actually there when you were shooting? Do you have any sympathy for blockbuster actors these days who have to do so much green-screen acting where they’re fighting … nothing?

I don’t have any sympathy for anybody who gets to do a big blockbuster today. It’s not like digging ditches. But in terms of working with nothing, it’s somewhat challenging. You have to imagine that there’s a scorpion in front of you. I went to Ray and I said, “How about I put my arm up and catch the tail just before it’s going to come down and get me, and then I slice it off with the sword?” And he says, “No. No, that will never work. Don’t even try it.” So, I do it anyway because, hey, camera’s rolling and they can cut it out if they want. He was so mad at me when I came off. I said, “I couldn’t help myself. I just imagined this thing stinging me and then I cut the tail off.” That shot is in the movie, even though he told me that he didn’t want me to do it.

Ray and I had some friction around a couple of things. There was another shot that I wanted to be in the movie. We were shooting at this Greek temple and I wanted to hold the head up like a Benvenuto Cellini statue. I wanted to approximate the exact same position as the Cellini statue. He said no, absolutely not, we’re not going to have that in the movie. And we’re walking out of the temple and it’s starting to rain. The cinematographer had the camera on sticks over his shoulder. I said, “Hey, put the camera down just for one second.” I got into that position. That moment is also in the movie. They were not happy with me on the set, let’s put it that way.

How do you feel about Bubo the robot owl 40 years later?

This is another reason why they did not like me. I called up Charles Schneer, the producer, and I said, “You can’t call this owl Bubo. I just read this book by [Albert] Camus called The Plague, and there’s only one thing that a ‘bubo’ is in the English language, and that is a bleeding pustule that appears under your arms in the later stages of bubonic plague. If you call this owl Bubo, it’s going to conjure up a blistering bleeding boil.” He said, “Only doctors will know that, and we’re not depending on doctors to make the box office.”

I rewatched Clash last night, and boy, those are some short togas y’all are wearing.

Before every take, there was a woman who had a bucket of baby oil and she would come up and slather baby oil over all of my exposed skin — which was most of it, because those togas were very small. Basically, the togas were shammies. I could’ve taken one back and washed my car. There wasn’t much to it.

They were so mad at me. I wanted to have something from the movie as an artifact, and they were so mad at me for — well, starting with my resistance to not cutting Medusa’s head off with a sword, and then not going on the press tour — they were going to give me the sword, but they never gave it to me.

Genre movies weren’t exactly cool and mainstream in ’80s the way they were today. Did you feel any sort of stigma as an actor in the wake of Clash?

I think there was some of that, but I think what was on the other side of it, the popularity that it had [outweighed that]. They wanted me to do a poster, I remember that — that’s another reason they were pissed off at me — they had a picture of me in the scene with the scorpions where I’m kind of splayed out with a sword in my hand. It looks a little bit like that famous Raquel Welch poster from that movie that she did. They had this whole poster campaign set up, and for the very reason you’re talking about, I declined to do it. I thought if there was that out there, then it would really stigmatize me and put me into a category of actor that would never be taken seriously again. But, it wasn’t Clash, it was Making Love that caused that to happen. That was the last studio picture I ever did. Clash wasn’t the problem, but playing a gay man in Making Love was a huge problem. It ended my career.

Well, you did all right.

Yeah, I just never made another [studio] movie. I went on TV, but I never made another movie.

Would you work in genre again? A big mythic epic — or the modern-day equivalent of one, a superhero movie?

If there was a role that was appropriate for my age in one of those big Marvel movies or whatever, I’d be happy to take it. I’m just all for work at this point in my life, and I’ve been very fortunate in the past nine weeks to have done three projects when most of my cohorts are not working at all, so I’m very fortunate for that. And I’ve been very fortunate in my entire career. Having done Clash was one of the highlights of that career from my point of view. It wasn’t necessarily from the producers’ point of view, but I loved it. I loved the traveling, and the horseback riding, and the fantasy, and the whole love story.

This interview has been edited and condensed.