On March 10, 2020, I drove from my apartment in Brooklyn to a weekend of club shows in Buffalo, New York, to work out new material for a theater tour.

Buffalo is one of those places I’ve always enjoyed visiting. My mother’s parents lived there for their entire lives, so as a kid I would always have at least one annual trip to Buffalo, a city I thought of as exotic. As an adult, I like Buffalo because I like the people at my shows and the hotel near the club and the people at the hotel and the coffee shops near the hotel and the people at the coffee shops near the hotel.

In general, those are the folks I encounter when I’m on the road. And I love being on the road. I like meeting people from all over the country and performing shows. I sometimes make this joke that people call me a “coastal elite” just because I live in New York and I’m better than other people. I understand where the trope comes from, but in truth, I’m not a coastal elite. Often, actual coastal elites will say to me, “It must be hard doing shows in the Midwest.” And I say, “No, it’s easier.”

That’s been my experience since I started driving my mom’s station wagon around the country to nightclubs from the age of 22. The further you go into more remote locations, the more people seem to crave live comedy.

When I was 24, I was asked to perform in Seward, Alaska, which has a population of 2,700 people. I was booked there by, I believe, the town of Seward. If memory serves, I was pretty terrible and the crowd was pretty great. Same with Fargo, North Dakota. I remember driving there with my brother Joe through many feet of snow and thinking, This show is gonna be as bad as these roads, and then it was one of the most appreciative crowds I’ve ever played for. I once played at a bar called Bunky’s in Ohio. Terrible, right? No, it was fun.

These types of shows are typically called “hell gigs” by comics — shows that don’t take place in clubs, but instead loud bars, town gymnasiums, bowling alleys, sometimes even laundromats. I’ve performed in the center of all-night college walkathons and in the deli lines of cafeterias in the afternoon. I’ve shown up to at least 30 shows that didn’t have a microphone and 100 that didn’t have a stage. Hell gigs are part of the job.

But the location actually doesn’t really matter. People just want to watch comedy.

Everyone’s reason for watching comedy is different, but for me, it’s the shared catharsis of a person onstage talking about the same anxieties you might be experiencing. Your botched first kiss is their botched first kiss. Your sleepwalking is their sleep apnea or whatever it is that keeps them up at night. At its best, stand-up comedy is one person taking the mic and providing the audience with an hour of escapism from the predictability of life. The comedian provides an assortment of twists and turns and misdirects and stories that feel like our own stories turned on their heads and packed with jokes. As an audience, we feel that simultaneous audience epiphany of That’s like me! combined with the shocked That’s nothing like me! The experience can be thrilling. In one moment, it shocks us, and in the next, it hangs a lantern on the universality of the absurd.

Stand-up comedy on TV can shrink the format. It can feel like reheated pizza. When you show up in Fargo or Seward, you’re delivering the fresh, hot pizza of comedy right to their door. Showing up in people’s towns cements the communal upside of comedy, which is that it isn’t just the comedian who is seen and heard, but it’s also the audience.

On March 11, 2020, I was driving to Buffalo via Ithaca, listening to epidemiologists on NPR weigh in on the spreading virus. I stopped at a local pizzeria called Thompson and Bleecker and sat down at the communal table. I was sitting with a couple of strangers who just drove in from Maryland, and they were concerned about the virus too. The guy said, “We were listening to Joe Rogan, and he had this scientist on, and we’re starting to think this is really serious.” That was the moment I knew I had to drive home. When the Venn diagram of Joe Rogan intersects with NPR, I know there’s something of a national consensus. Things are bad and are about to get worse.

I drove the four hours back to Brooklyn. We postponed the Buffalo shows for what we thought was a shocking amount of time: four months. My agent asked me to consider doing some virtual shows, to which I was completely resistant. I remember my brother Joe and I laughing at the sheer idea of it. “What’s next, Zoom comedy?”

Well, yes, actually. The next person I talked to was comedian Sam Morril, who had done some of these Zoom comedy shows. Sam said to me, “I actually get a lot out of it. I also didn’t expect that not only are you performing for people who can’t leave their houses from the shutdown, but you’re also performing for people who maybe couldn’t even leave their houses before COVID.” That’s when I decided I would try this at least once.

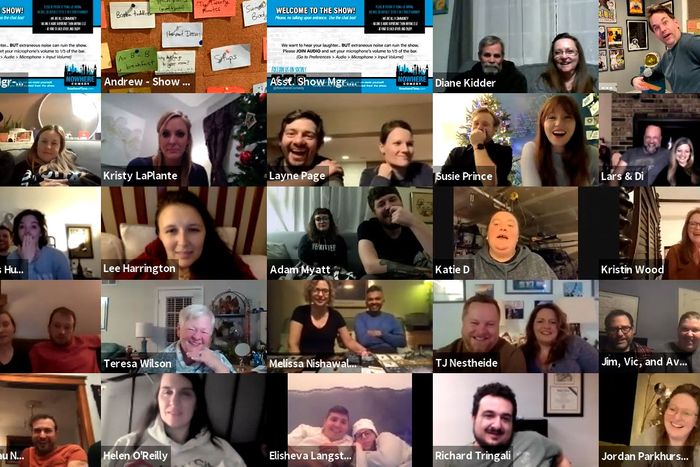

In summer 2020, I did one night of Mike Birbiglia: Working It Out Virtually for 500 people who were located around the world. It was weird. And fun. Then I decided to do more.

I started adding virtual crew members: a cinematographer, a sound technician, a director. We added three more iPhones to give us new camera angles. We lit my brother Joe’s Rhode Island office like a TV studio. It became this strange hybrid stand-up comedy interactive talk show.

What I discovered was that the same thing people enjoyed about the live shows were things they were able to enjoy on the Zoom show. One of our producers noticed that during one of the shows someone wrote in the live Zoom chat: “I can’t unmute! I want to laugh!” Those folks were unmuted by the hosts. They were seen. They were heard.

So much of comedy is about turning reality on its head, but at this moment in history, reality itself has already been turned on its head. We’re living in the science-fiction future we had imagined. Instead of gathering in rooms for jokes, we’re in 1,000 different rooms that become one room for one hour.

The clubs and bars and theaters and even laundromats and bowling alleys were closed. Instead, people Zoomed in from the most remote locations: living rooms with their cats and dogs and rabbits, gathered around bonfires with whiskey, families huddled in their children’s playroom because it has the best Wi-Fi, a woman knitting a shawl in her TV room, a couple carving a pumpkin with their family in the kitchen. Five continents and over 20 different countries were represented. Part of the enjoyment was not just my jokes, but peeking into people’s lives, witnessing this surreality together, and laughing.

I’ve done about 18 of these virtual shows, and I’ve learned things from them that I thought I had long understood after 20 years of being a professional comedian. People need comedy. At very least, they need to laugh — particularly when life is most burdensome and unwieldy. People need to laugh to be reminded what laughter feels like and why anyone would have laughed in the first place. It’s the defibrillator that sends a shock to the heart to restore a normal rhythm.

I’ve received more thank-you notes in the span of these last 11 months than I’ve received in years. It’s probably not my best work; I’m writing it on the fly. But I enjoy it because I feel connected to people all over the country and all over the world.

I’m not saying it’s ideal. Arguably these are the worst conditions imaginable for comedy, but I think the people participating appreciate that I’m showing up at all. I mean, let’s be honest. It’s a hell gig.

Mike Birbiglia is a comedian, filmmaker, and the author of Sleepwalk With Me and The New One. He is the host of the podcast Working It Out and is performing five Working It Out Virtually shows on Valentine’s weekend — 100 percent of the proceeds from the 9:30 p.m. Valentine’s show, featuring special guest Maria Bamford, will be donated to regional food banks.