For years, Edward Zwick was primarily known as a television guy. He had come up through the TV ranks and had created, along with his writing and producing partner, Marshall Herskovitz, the hit series Thirtysomething. Later, he would also executive-produce the well-received Once and Again and My So-Called Life. Along the way, however, he also became a director of cinematic spectacles. Glory (1989) and Legends of the Fall (1994) were big award-winning period epics. Courage Under Fire (1996) and The Siege (1998) were topical, large-scale dramas.

In his lively new memoir, Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions: My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood, Zwick tells lots of stories about his up-and-down journey through the film and television industries. Among the most fascinating is his account of the making of 2003ÔÇÖs The Last Samurai, a rousing war epic about a 19th-century rebellion by a group of samurai opposed to the rapid westernization of Japan. In it, Tom Cruise plays an alcoholic American officer, haunted by his role in the Indian Wars, who joins in with Ken WatanabeÔÇÖs Lord Moritsugu Katsumoto, the leader of the uprising and the ÔÇ£last samuraiÔÇØ of the filmÔÇÖs title. (At one point, Zwick writes, Russell Crowe called him about trying to play the Katsumoto character.)

The film was a huge hit, and today it feels emblematic of a bygone era of entertaining, star-driven period adventures. ItÔÇÖs also revered in the stunt community for its elaborate action sequences, full of impressive riding and sword-fighting, and its sprawling battle scenes. ÔÇ£It wasnÔÇÖt Lawrence of Arabia, but we tried,ÔÇØ Zwick writes. The story of its making offers an insightful glimpse into what it takes to mount such a massive production with the biggest star in the world.

Excerpt from ÔÇÿHITS, FLOPS, AND OTHER ILLUSIONSÔÇÖ

Until this moment in my career, getting a movie made had been a war of attrition. The subjects that interested me never seemed to fall neatly into a category that was easy for executives to understand, by which I mean, to sell. IÔÇÖd come┬áto expect a kind of siege mentality ÔÇö haranguing, shaming, whining, bullying, and┬ágenerally making myself so annoying that I occasionally managed to wear them┬ádown until they gave me a start date. Such difficult births are quite common in the┬ábusiness. Every year during the orgy of self-congratulations we immodestly call┬áÔÇ£awards season,ÔÇØ you can count on someone in a tuxedo giving a tearful acceptance speech citing the decades of rejection that preceded such a halcyon moment. So much of Hollywood studio culture is fear-based: executives afraid that┬áthe wrong decision could cost them their jobs. I was accustomed to a gradual and┬ásometimes grudging process of acceptance, often taking several weeks of dailies,┬áor a first cut, sometimes even a successful preview for them to get excited about┬áwhat they had on their hands. The reasons a studio decides to make a film are often quite obscure unless weÔÇÖre talking about a superhero movie or big IP (intellectual property). On such corporate crusades, long before a single frame is filmed, a legion of marketers, accountants, and distributors have already run the┬ánumbers on its profit-and-loss profile, a release date has been set, and an advertising campaign is underway. But the path of a ÔÇ£one-offÔÇØ (thatÔÇÖs what they now┬ácall regular movies) as it struggles to swim against the mainstream is littered with┬árevised drafts and broken hearts. Deliberately or not, a studio will do anything it┬ácan to make a script more ÔÇ£accessible.ÔÇØ One thing you learn, when they call it a┬áÔÇ£passion project,ÔÇØ you know youÔÇÖre in trouble.

The Last Samurai was an entirely different experience: the only time it felt like┬áa studio was genuinely enthusiastic about what I had in mind. The movie had a┬ágreen light from the moment Tom said yes. It was like the no-bid, cost-plus contracts IÔÇÖd heard about between military contractors and the Defense Department.┬áA million dollars of R&D to scout locations, hire department heads, and figure┬áout logistics? No problem. A trip to Japan to do research and meet actors? Let us┬ámake the reservations for you! You want to shoot on three continents? Great idea!┬áWithin weeks we were in headlong prep. My first trip to Japan was overwhelming; I visited museums, met historians, and traveled all over the country. There was so┬ámuch I didnÔÇÖt know, and even more that weÔÇÖd gotten wrong in the script. Since at┬áleast a third of the movie would be in Japanese, I needed help with the dialogue. The great screenwriter Y├┤ Takeyama agreed to join me.

Vickie Thomas (the casting director whose impeccable taste IÔÇÖve come to rely on for 20 years) had arranged for me to meet Y├┤ko Narahashi in Tokyo. Y├┤koÔÇÖs ostensible role would be to help cast the movie, but it was soon clear she┬áwould be much more to me than a casting director. Bicultural and brilliant ÔÇö her┬áfather had been the Japanese ambassador to Sweden ÔÇö she was also a theater director and a teacher with her own acting school. In addition to serving as my┬átranslator and interlocutor, her insights into the nuances of culture and behavior,┬áon set and off, saved me from innumerable gaffs, while her intimate knowledge┬áof her countryÔÇÖs unusual casting traditions was a godsend. Like many institutions┬áin Japan, casting was often hierarchical. To play a part like Katsumoto, starring┬áopposite Tom Cruise, it was assumed that Hiroyuki Sanada ÔÇö often referred to as┬áthe ÔÇ£Tom Cruise of JapanÔÇØ ÔÇö would be cast in the role. But upon meeting Ken┬áWatanabe, I was so taken with his unusual blend of strength, humor, and emotional availability that I decided to cast him.

Upon hearing of my choice of Ken, the Japanese representatives from Warner┬áBros. made no secret of their displeasure. They informed the executives back in┬áBurbank that this was a terrible faux pas. It was Hiroyuki Sanada himself who came┬áto the rescue. By agreeing to play Ujio, KatsumotoÔÇÖs majordomo, he was making┬áa strong statement in support of Ken and the movie. I couldnÔÇÖt have known that┬áafter surviving a battle with leukemia years before, Ken had found himself in debt┬áto shady managers; at that time, the Yakuza was heavily involved in the business.┬áTo pay them off, for several years he had been obliged to play whatever roles on┬áJapanese TV came his way, no matter how uninspiring, and it had hurt his career.┬áIn our early rehearsals, Ken seemed somewhat tentative, but SanadaÔÇÖs deference┬ánever failed to endow his presence with the necessary aplomb. Day by day as his┬áself-confidence grew, so did KenÔÇÖs performance. By the time we were ready to┬áshoot, he had grown into the role, owning not just his size as the character but as┬áa leading man going mano a mano with the biggest movie star in the world.

While reading a book about the Meiji dynasty I had seen a picture of an┬áancient monastery and asked if we could visit it. It turned out that the 700-year-old Buddhist compound was located atop a mountain outside┬áHimeji, a midsize city. To reach it required taking a rickety funicular. But┬áonce there, walking the hand-hewn floors through temples shrouded in clouds┬áwas like being cast back in time. When I told the Warner physical production┬ápeople I wanted to use it as KatsumotoÔÇÖs home, I expected to be laughed out┬áof their office. But I had forgotten this was a Tom Cruise movie. They figured┬áout a way to make it work. There were just as many things I would have liked┬áto shoot in Japan that proved too costly; there simply wasnÔÇÖt the kind of open┬áspace and vistas we needed to stand in for the pastoral splendor of 19th-century Japan. I had been to New Zealand once before with my wife and kids┬áfor a backpacking trip on the Routeburn Track, a three-day trek through alpine meadows, emerald-green tarns, prehistoric ferns, and spectacular vistas. It was a┬ánorth-south mountain range, as was JapanÔÇÖs. Lilly Kilvert, John Toll, and I spent┬áweeks flying up and down the North and South Islands in a helicopter ordinarily reserved for the prime minister (a Tom Cruise movie, remember?) until we┬áfound a pristine valley in which to build KatsumotoÔÇÖs village. There, Lilly would┬ábring Japanese carpenters to build the houses in the traditional sashimono style┬áof wood joinery without nails. She also began planting rice paddies that wouldnÔÇÖt be shot until the following spring.

Back in L.A., it was a cold, rainy winter. One wet evening, Marshall Herskovitz and I┬áwere scheduled to meet with Tom about the script. In addition to helping me┬áproduce the movie, Marshall had joined me in the rewrite ÔÇö not only because the┬áburdens of preproduction were beginning to overwhelm me but because, much┬áas I hated to admit it, I knew his unique gift would bring the script to the next┬álevel. Also, because he insisted. He has a great love of the epic form, and his ideas┬áand criticisms, however painful to hear, were brilliant. Tom quickly recognized┬áMarshallÔÇÖs ear for dialogue as well as his gift for sly humor and began to rely on┬áhim. This became something I depended on more and more as the demands of┬áshooting drew closer.

After Marshall and I finished another draft, I got a call from Robert TowneÔÇÖs┬áassistant asking if I was available to meet. I knew that Towne ÔÇö one of the few living writers in my personal pantheon ÔÇö had an informal arrangement with Tom┬áwhereby he sometimes quietly rewrote his movies. I drove over to his house in the┬áPacific Palisades, harboring more than a little dread. Had Tom asked him to rewrite us? It turned out Towne didnÔÇÖt want to talk about the script, except to point┬áout several things heÔÇÖd enjoyed. Apparently, he just wanted to take my measure.┬áStill, as we spent a pleasant couple of hours talking about John Fante novels, it did┬áfeel like he was giving me his blessing.

That night, Marshall and I arrived at TomÔÇÖs house for a meeting and were told┬áhe was down at the tennis court. We followed a winding path through the fog toward the sound of strange percussive whacks, each accompanied by loud, guttural┬ácries. Below us, we could barely make out five spectral figures hacking at each┬áother with wooden swords. Though principal photography was still six months┬áaway, Tom was already working out every day, determined to do the scene where Algren takes on four assailants in a single take without a cut, chanbara style, as in the old samurai movies. No stuntman was going to play his part.

There was one stunt we knew would be too dangerous. The moment the samurai are first revealed, emerging on horseback out of the misty forest, needed to be violent and terrifying. As we had written it, Algren, a former cavalry officer,┬ádraws his saber and fights while on horseback. As the conclusion of the sequence, Marshall and I had imagined him getting T-boned ÔÇö his horse deliberately struck┬áby another horseman, with Algren knocked to the ground and his horse falling┬áon top of him. There was no way to do the stunt with Tom on a real horse, where┬áthe slightest wrong movement could put his head in the path of a swinging metal┬ásword, nor could we really have one horse hit another, let alone have TomÔÇÖs horse┬áfall on top of him. So how to do it?

These days it would all be done with CG, but that was still years away. To┬áshoot it in cuts using a stuntman would inevitably look staged and give the gag┬áaway. It was Paul Lombardi, our special-effects guru, who suggested building an┬áanimatronic horse. It took months of experimentation, repeated failure, and reimagination, but six months and a million dollars later, Tom Cruise is fighting┬áon horseback in the middle of a m├¬l├®e, or so it appears, and the real Tom Cruise┬áhas a live horse falling on him. IÔÇÖve never counted how many seconds of the fake┬áhorse ÔÇö Wilbur, as he affectionately came to be known ÔÇö are in the final cut, and┬áI defy anyone to identify him without going frame by frame. All I know is theyÔÇÖre┬áthe most expensive frames of any film IÔÇÖve ever shot.

Our first day of shooting was in the Buddhist monastery. Riding up the funicular at dawn, we were enveloped by clouds. Moments later we broke through┬áto be confronted with what looked for all the world like a clich├® ÔÇö the perfectly┬áround, bright-red sun of the Nippon flag rising over distant mountains and setting┬áthe ancient temples aglow. Soon after, the entire crew gathered under the gaze of┬áa 14-foot-high Buddha. Surrounded by hundreds of lit candles and dizzying┬áincense, we accepted the monksÔÇÖ blessings of good luck for the film. At lunch they┬áeven made us seasonal bento boxes of sashimi adorned with colorful fall leaves. It┬áwas as magical a time as IÔÇÖve ever had on set.

After lunch we were to shoot the first scenes to be performed entirely in Japanese. IÔÇÖll admit to being a bit nervous, yet as soon as the actors began to speak, I┬árealized that although I couldnÔÇÖt understand the words, their intentions were perfectly clear. At first, IÔÇÖd confer with Y├┤ko after every take. Did their performances┬áseem natural? Were their line readings correct? If I had an adjustment, she would┬ácommunicate it to the actors. But after a while, I began to allow my instincts to┬águide me. These were scenes weÔÇÖd written ourselves, after all, so it made sense I┬ámight be able to follow along with its beats and rhythms. It was, I suppose, what┬ádirecting silent films must have been like. Most surprising was how many times IÔÇÖd┬ásee Y├┤ko nod her head after I said I preferred a particular take. Remarkably, it was┬áoften her favorite as well. I was especially pleased as KenÔÇÖs sense of humor began to┬áinform his performance. Over the course of a taxing shoot, that quality would prove┬áto be a saving grace. He is one of the most delightful, soulful men IÔÇÖve ever met.

We shot in Japan for two weeks, mostly in Kyoto. After we wrapped on the┬á last night, Sanada took Ken, Marshall, Y├┤ko, and me to his favorite karaoke bar.┬á I walked in expecting something glitzy and high end. It was just the opposite. No┬á bigger than a shipÔÇÖs stateroom, there were only five seats at the bar, and Sanada┬á had reserved the place just for us. ItÔÇÖs possible he knew just how boisterous we┬á would get. When Sanada entered, I thought the bartender was going to faint. It┬á turned out, in addition to Y├┤koÔÇÖs many talents, she was also a songwriter whose┬á tunes were there on the jukebox. Ken turned out to have a spectacular voice and┬á loved to sing American pop standards. (He would go on to be nominated for a┬á Tony for his performance in The King and I.) One of my favorite memories of┬á all time is seeing Marshall, a nondrinker, shit-faced for the first time in our long┬á friendship, clutching the mic and crooning ÔÇ£Danny BoyÔÇØ at the top of his voice in┬á a rich basso profundo.

We flew back to L.A. for the second leg of our worldwide production. ItÔÇÖs┬áhard to describe my wonder and delight as I walked onto the Burbank lot and┬áfound the famous New York Street completely transformed into Tokyo, 1876. LillyÔÇÖs production design was a marvel: every detail from the live eels to the wood┬ájoinery. Same with costume designer Ngila DicksonÔÇÖs hand-painted kimonos and┬ágleaming armor.

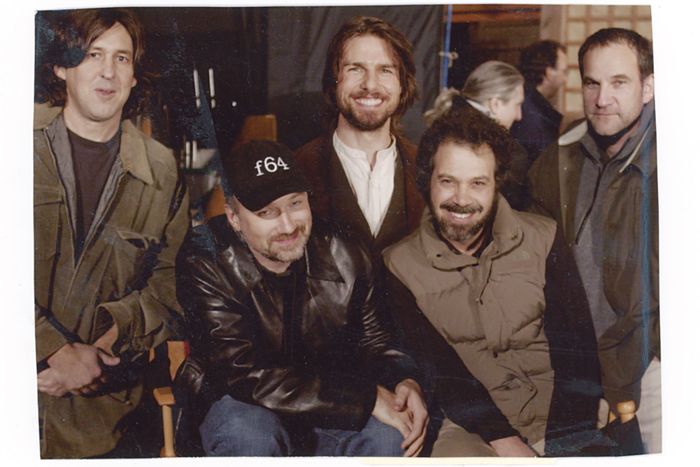

On our first day of shooting in Burbank, I happened to glance behind me and┬ásee Steven Spielberg. Moments later, David Fincher appeared, and then Cameron┬áCrowe. How coincidental that theyÔÇÖd all ÔÇ£just happenedÔÇØ to be on the lot that day.┬áI would later discover each was courting Tom to be in their movies and this was a┬áchance to get a bit of face time. I will confess to being the tiniest bit self-conscious┬ágiving direction with that intimidating trio on my six (as they say in Top Gun). But┬átheir visit prompted an oddly charming and very revealing reaction from Tom.┬áWhile Fincher, Crowe, Marshall, and I were chatting behind my chair, the still photographer asked if he could take a picture. Tom must have been with Spielberg at the time, but when he heard about it, he asked for a copy and had himself┬áphotoshopped into the shot. Apparently, even movie stars have FOMO.

Shooting went well the first week, and then we hit our first speed bump. It┬áseems the neighboring houses had grown tired of the noise caused by productions shooting deep into the night and had gotten wind that we were planning more late┬ánights by the little pond at the border of the studio known as ÔÇ£GilliganÔÇÖs Lagoon.ÔÇØ┬áThatÔÇÖs where we had built a set for KatsumotoÔÇÖs Tokyo home. As a compromise┬áwe agreed to shoot split days ÔÇö from noon until midnight ÔÇö rather than work all┬ánight long.

We had already agreed not to use black powder in the antique rifles ÔÇö again,┬ábecause of the noise. The solution by the armorer was to turn the weapons into┬áwhat essentially were battery-operated toys. When the trigger was pulled, a flash┬áwould appear, followed by a puff of smoke. The sound would then be added in┬ápost. It sounded swell in theory, but from the outset of shooting KatsumotoÔÇÖs┬áescape we discovered the gag rarely worked, and even when it did, it took far too┬álong to reload for the next take. After only an hour of shooting, we were several┬áhours behind.

Going into the second night of filming the sequence, we had lost at least┬áhalf a day and I was getting worried. How would the studio respond to us falling behind so soon? To executives always ready to panic about the budget, it┬áwould augur worse to come. At lunch ÔÇö in this case, that meant 6 p.m. ÔÇö I was┬áscheduled to have a meeting with the marketing department. Sweaty and stinking┬áfrom the pond, I walked into a huge conference room and found it brimming┬áwith no less than 40 smiling faces. For an hour they regaled me with their┬áplans for the movieÔÇÖs release: billboards, talk shows, magazine covers, trailers,┬áinternational premieres. I did my best to pay attention while unable to banish the┬ásingle thought hammering my brain ÔÇö WeÔÇÖre behind. WeÔÇÖre behind. How bad will┬áit be┬átonight?┬á

It got worse. A couple of hours later, while still moving at a crawl, I was waiting for a lighting setup that was taking much too long (night lighting setups always take too long) and anxiety-mainlining peanut M&MÔÇÖs at the craft-services table┬áwhen Tom ambled up. He greeted me with his usual, peppy ÔÇ£HowÔÇÖs it going?!ÔÇØ I┬áwasnÔÇÖt in the mood to respond in kind.

ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know,ÔÇØ I moaned, ÔÇ£the sequence isnÔÇÖt really working. Those stupid┬á guns are killing us. WeÔÇÖre already behind and IÔÇÖm worried weÔÇÖre going to have to come back and reshoot at least half of it.ÔÇØ He listened as I went on. Then he┬á looked off into the night.

ÔÇ£Hmmm┬áÔǪÔÇØ

That was all he said before touching my shoulder and walking away. I stood┬á there, confused. CouldnÔÇÖt he tell I was upset? Had he been in this situation so┬á many times that he just took it in stride? It was then that I began to realize the gulf┬á between my experience and TomÔÇÖs. No matter how many movies IÔÇÖd made until┬á then, no matter how many battles IÔÇÖd had with studios, or times IÔÇÖd gone over┬á schedule, there was still some part of me that needed to be a good boy.

When I ran into Marshall, I recounted my non-conversation with Tom. Mar shall smiled and said, ÔÇ£He knows thereÔÇÖs not going to be a card in the credits that┬ásays, ÔÇÿThis movie was made on schedule.ÔÇÖ ÔÇØ Then he touched my shoulder exactly┬áthe way Tom had done and headed back to the set. Later that night, as I was setting up a shot, Cruise was passing by and stopped. ÔÇ£How ya doing, boss?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Better,ÔÇØ I said.

ÔÇ£Good, GOOD! You know what we get to do tonight?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£What?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£MAKE A MOVIE!ÔÇØ

As he walked away, I realized IÔÇÖd missed the subtext of our earlier interaction.┬á It had been TomÔÇÖs nonconfrontational way of reminding me I was the director, and┬á that directing was a samurai job. He didnÔÇÖt want to see me shaken. We were going┬á to be shooting for another hundred days. If I was willing to compromise now, I┬á might compromise tomorrow, and thatÔÇÖs not the way he rolled.

I called the studio in the morning and told them we needed to reshoot. They didnÔÇÖt say a word in protest.

After New YearÔÇÖs, our huge traveling circus moved to its third continent. New Zealand was a dream. My family and I stole a delirious week in a house by the Tasman Sea before production started up again. The bracing weather changed┬áhourly as storms moved in and out while we explored snowcapped mountains,┬áshadowed glens of dense ferns, and fog-shrouded fjords. My daughter learned to┬ásurf, and my son went backpacking. I even had time to remember I was married.┬áSooner than I would have liked, Kevin de la Noy called to say I needed to come┬áinto the production office. Kevin had taken over as line producer once the scope┬áof our ambitions revealed the need for someone of his unique genius. I had first┬ámet Kevin 15 years before when he was the location scout on the first incarnation of Shakespeare in Love. In the years since, this English logistics genius had┬árisen to rockstar status: planning the logistics for the climactic battle in Braveheart,┬áorganizing the beach assault in Saving Private Ryan. I could hear in his usually jolly voice that he was beginning to suspect his greatest challenge loomed in the weeks ahead.

There are few Japanese in New Zealand. How then to populate the cities,┬áseaports, and villages we had built? The answer was obvious: bring them over.┬áThis would prove harder than it seemed. In addition to auditioning thousands of┬áÔÇ£fighting extrasÔÇØ so as to find 700 with the ability to learn 19th-century fighting tactics, rounding up another couple hundred women and children, getting them all the necessary visas, and then leasing the 747s to fly them in,┬áKevin had to create an entire colony of translators, doctors, and chefs to accommodate them all.

Our base of operations was New Plymouth, a small oil-and-gas town on the┬á North Island. Within a week it looked like an occupying army had taken over.┬á Every laborer with a pickup truck was put to work, every piece of heavy machinery was commandeered. The restaurants and hotels were booming. As the┬á extras came to recognize me as their meishu (a classier honorific than ÔÇ£directorÔÇØ),┬á I couldnÔÇÖt walk down the street to buy toothpaste without accepting and returning┬á any number of gracious bows. Not that I minded.

In addition to the Japanese cast I had hired Tony Goldwyn as Colonel Bagley,┬áAlgrenÔÇÖs former superior officer in the Seventh Cavalry, and Billy Connolly as Sergeant Zebulon Gant, in what I liked to think of as the Victor McLaglen role ÔÇö the┬ágruff, stalwart noncom straight out of a John Ford movie. Tony, a talented director┬áhimself, was a joy to be with, on set and off, while Billy was irrepressibly funny in the way I imagined working with Robin Williams must have been. At times I┬áliterally had to beg him to stop making us laugh so we could get back to work.┬áKen WatanabeÔÇÖs commanding performance continued to thrill me while I came┬áto count on SanadaÔÇÖs vast experience in martial arts (known as Seiten wo Tsuke,┬áliterally ÔÇ£reach beyond the blue skyÔÇØ) to help me stage the many fighting scenes.┬áKoyuki, the actress playing the role of Taka, AlgrenÔÇÖs reluctant host, was the greatest revelation. Her understanding of period behavior was expressed with exquisite┬ásimplicity and elevated every scene.

Working with Tom was joyous, challenging, and exhausting. His energy was┬á intimidating. It may sound surprising, but the one formative experience we had in┬á common was that we both wrestled in high school. Like all wrestlers, we shared a┬á tolerance for hard work and punishment. Tom was in every scene for 120 shooting┬á days, yet he never showed the slightest sign of fatigue, not even after getting the┬á shit kicked out of him by Sanada take after take in the mud and pouring rain.┬á Tom likes to think of himself as being chased by a shark, which he means metaphorically. I hope. His mantra when giving notes is, ÔÇ£How can we ratchet up the┬á pressure on my character?ÔÇØ By which he means, he wants a bigger shark.

He is also legendarily, at times maddeningly, self-confident, no matter if itÔÇÖs┬áabout doing a dangerous stunt or a six-page dialogue in a single take. But there┬áwere times that very self-assurance could look opaque on film. And it was the┬áopposite of what I wanted to see in him when, on the eve of the final battle, he has┬áto say good-bye to Higen, the son of the man he killed. We were to shoot the scene┬áat magic hour, an ineffably beautiful time in the village weÔÇÖd constructed in New┬áZealand. Given that Algren knows he probably wonÔÇÖt ever see it again, I thought┬áthe fading light was appropriate. But it also meant Tom would have time for no┬ámore than a single take. This, I thought, gave it a degree of difficulty much higher than the most difficult stunt. If I hoped to get him to the right emotional place, I┬áfelt I needed to touch some vulnerable part in him that IÔÇÖd yet to see him reveal┬áin the movie.

I donÔÇÖt mean to suggest he wasnÔÇÖt completely open to my direction. If I had┬áasked him to do a scene while standing on his head, IÔÇÖm convinced he would have┬ábeen willing to try. If I had said, ÔÇ£Listen, Tom, could you be just a tad more emotionally revealing in this scene?ÔÇØ he would have given his all. But the result would┬áhave invariably ended up feeling forced ÔÇö precisely because he was trying to give┬áme what I wanted. I didnÔÇÖt want him to try to make something happen. I wanted it to happen.

While filming their earlier scenes together I had noticed how sweet and attentive Tom had been with the young actor playing Higen. Over the months of┬ágetting to know Tom, IÔÇÖd also observed how close he was to his 8-year-old son,┬áConnor. As the crew scurried to make ready, we were already losing the light. I┬átook Tom aside.

ÔÇ£Tell me about your son,ÔÇØ I said.

He looked at me, surprised. I knew Connor had just returned to L.A. and┬á Tom wouldnÔÇÖt be seeing him for a while. For a moment Tom was quiet. And then┬á he began to talk. It doesnÔÇÖt matter what he said in those few short moments in the┬á fading light. I watched as he looked inward, and a window seemed to open and┬á his eyes softened.

ÔÇ£Go,ÔÇØ I said, gently nudging him into position on the porch. He nailed the┬á scene with the depth of feeling I had loved in his best performances. I should also┬á mention his Japanese pronunciation was spot-on.

The light was gone. The AD called, ÔÇ£Wrap.ÔÇØ As Tom walked past me on his┬á way down the mountain, he caught my eye and mouthed, ÔÇ£Thank you.ÔÇØ

Excerpted from HITS, FLIPS, AND OTHER ILLUSIONS: My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood by Ed┬áZwick. Copyright ┬® 2024 by Ed┬áZwick. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Things you buy through our links may earn us a commission.