My favorite sequence in the 2007 Bollywood movie Om Shanti Om, a minor postmodern masterpiece from director Farah Khan, comes early in its nearly three-hour run time. It’s a song-and-dance number, and I’m hardly alone in my fondness for it. “Dhoom Taana” — which penetrated a wider consciousness in 2014, when the Indian American woman who would go on to win that year’s Miss America contest performed her version during the talent section — is a proper banger; its popularity is one reason the film set box-office records: melodically and lyrically catchy and mischievous; visually striking, with its stitched-together collage of old films; and, as a dance number, exuberant and elegantly athletic. But what makes this cheeky, pastiched homage to Bollywood most alluring is the particular way the sequence subverts gender roles, inside the film’s larger parodic enterprise. Perhaps it makes sense that the figure on whose efforts this delicate exercise largely rests is the megawatt actor Shah Rukh Khan, maybe the only Indian superstar suited for the task.

What is it about SRK? He is at once the biggest and most versatile of Bollywood heroes, a star said to command a larger fan following than any other working actor in the world today, a man who does psychological thriller, screwball comedy, earnest romance, ditzy rom-com, serious biopic, and, lately, testosterone-fueled action. He’s said to be five-feet-seven, shorter than some of his female co-stars, seemingly still in full possession of his springy hair, and is physically muscular yet lithe, with a dancer’s grace, as if Gene Kelly had dabbled in steroids. Other heartthrobs of his generation and stature — Salman Khan with his rigid musculature; Aamir Khan, chilly and slightly cerebral; Akshay Kumar with his square frat-boy face — can seem as inflexible as plastic superheroes in Mattel boxes. But SRK is chameleonic, sensual, even as he stays unerringly poised and polite in interviews and on social media, as if he signed a contract for statesmanlike celebrityhood in blood. At 57, he still conveys a whiff of the unconflicted naïveté of 1990s Bollywood superstardom, when gold was an absolute good and fame an incontrovertible blessing. One nickname, “Brand SRK,” feels all too fitting, if unwittingly so, for a populist golden goose willing to lend his image, name, and endorsement even to products as unsexy as ballpoint pens and air conditioners. “Tide,” he is pronouncing at this very moment in some household on the subcontinent, “is the real SRK,” meaning the “stain removal king.” Yet a funny aliveness inevitably roughs up all his performances, a suggestion that he is highly sensitive to the bizarre pageantry of his life and of the industry.

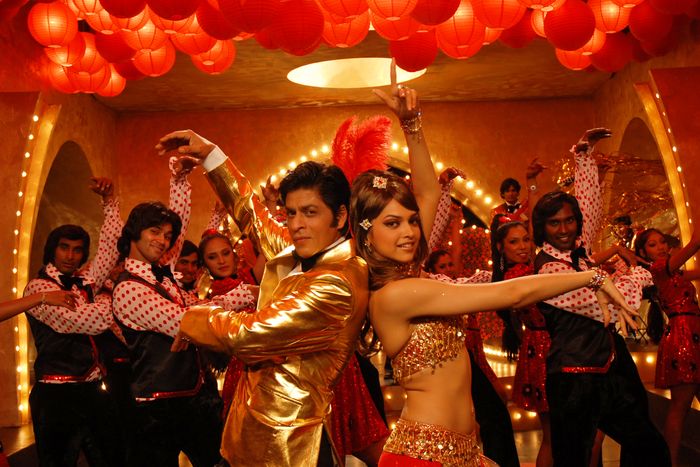

Nowhere is this self-awareness more evident than in Om Shanti Om. The film, often called a love letter to Bollywood, skewers the industry’s foibles (among them nepotism and melodrama) with precision. It’s an homage in every sense, including in how it requires of its performers that they operate in all of Bollywood’s high keys — comedy, drama, action — convincingly, within a single movie. In the palimpsest of “Dhoom Taana,” which inserts the movie’s stars — Khan and, notably, Deepika Padukone, a superstar in her own right today, here in her debut role — into vintage Bollywood footage, the film’s playful skewering reaches a zenith.

Padukone plays Shanti Priya, an “It”-girl actress in 1970s Bollywood — loosely inspired by the legendary beauty Hema Malini — for whom Khan’s character, a struggling actor from the tenements named Om Kapoor, nurses a one-sided infatuation. In an early scene, he’s in the cheap seats at the premiere of her movie. When the curtains open, a film inside our film starts: The item number “Dhoom Taana” reveals Padukone as Shanti Priya, superimposed into the fuzzy romance of the palace in the 1966 period film Amrapali. The editing trick isn’t part of the fiction of Om Shanti Om, of course, but we outside viewers are in on the diegesis. Against the muted colors of the remastered film, Padukone as Shanti Priya shines with a hyperalive splendor. (Padukone, daughter of the badminton champion Prakash Padukone, conveys that rare mix of sport and glamour, health and excess, that makes, say, Charlize Theron, powerfully alive onscreen.) Dressed in a tangerine-colored dance sari, her midriff and arms bare, she brushes against a remastered Sunil Dutt, playing a stoic BCE emperor, shirtless and mustachioed, serene and slightly ghostly, his epicene 1970s torso a surprise.

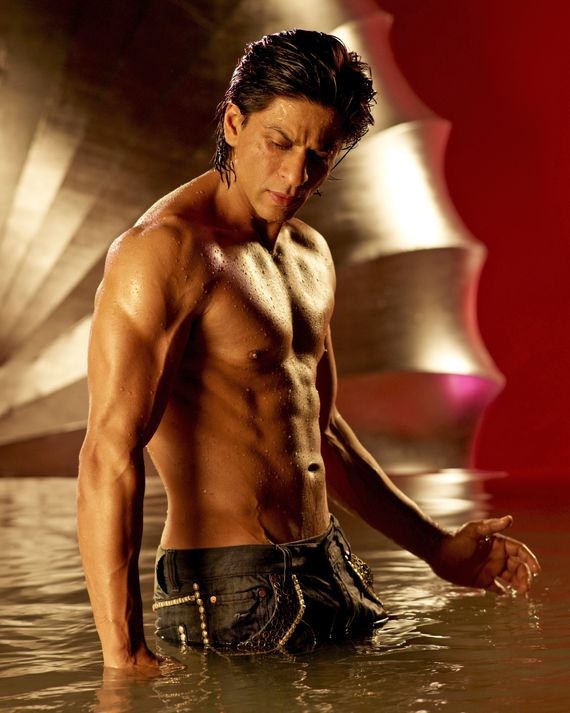

The serenade is interrupted by Om Kapoor’s daydreaming. Suddenly, we are in his fantasy — it’s he who is the hero. Shah Rukh Khan’s body, not Dutt’s, captures our attention, as vibrant as Padukone’s in the flickering palace, 2000s muscled rather than 1970s undefined, and desperate for the woman rather than the other way around. We’ve watched SRK play the dashing fool before — after making an entrance with villainous, creepy roles, he shot to global fame in the late 1990s, baring his heart, and occasionally his chest, to audiences in India and across the diaspora in a series of rom-coms (and the most picturesque of rom-drams, Dil Se). With Om Shanti Om, he pulls off an uncanny complexity.

“What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine,” Susan Sontag wrote in her classic text Notes on Camp, in which she calls androgyny a hallmark of camp sensibility. And Khan, as the naïvely ambitious, lovesick Kapoor, telegraphs as somehow half-man and half-woman, half-empowered and half-doomed, a perfect ambassador for the campiest of film industries. (Let’s presume Sontag hadn’t seen a Bollywood movie, already flamboyant in her time, or else how to explain the genre’s exclusion from her piercing eye?) He waggles his eyebrows, bounces goofily on beat, his heart set on a woman who will never be his, in a world he will never conquer. His movements are slightly too much, desperate.

But that vulnerability is laced with a cool self-assurance. He seduces as he pleads. Is it Om Kapoor we see? Or Shah Rukh Khan in his greatest performance yet? The superstar, pretending to be the opposite? Padukone, a newcomer playing a star, next to a real one playing a nobody, participates in this inversion: Is she the hero, or is he? Is she in control, or is he? When, midway through the movie, Om Kapoor dashes into a fire that’s broken out on set to rescue Shanti Priya — another reference to a deep cut of Bollywood lore (the story of how the actress Nargis fell in love with none other than Sunil Dutt after a similar rescue) — his movements again throw inversions into relief. She is the VIP on set; he is the peon … or? He carries her out of the flames, stumbling slightly, but a new strength in his gait competes with the obsequiousness. His face flickers with a mix of disbelief and certitude; her eyes are on him. For a moment, as in the best romances, whatever is between them seems larger than the structures that hold them, pure, unvarnished.

Like so many figures who capture mass attention, Shah Rukh Khan can seem to have been born to throw matters of identity into question. The son of a Pathan father from Afghanistan and a Hyderabadi mother, he grew up in Delhi, a middle-class boy who attended a prestigious local private school. That history helps explain his appeal, or so argued a pair of born-and-bred Mumbaikers to me recently: He’s the rare outsider to become Bollywood’s consummate insider, a carefully educated convent-school boy in a sea of unworldly nepo babies who know nothing else. This pedigree is also why, they suggested, he’s kept a relatively sterling reputation, free of the rumors of ultrasleazy or violent behavior that attend some peers. In college, Khan began to study acting and left a master’s degree in communications early to pursue an acting career. In his mid-20s, before he was a household name, he married Gauri Chhibber, a hometown sweetheart, a Delhi girl known to him since he was 18 and she was 14, according to an interview he gave in the 2005 BBC documentary The Inner Life of Shah Rukh Khan. They settled in Bombay, the city where his second life began; his parents had both died in their mid-50s. Khan is Muslim, his wife Hindu.

Om Shanti Om, in line with its mandate to parody, revolves around a reincarnation plot, one of those Bollywoodian devices that draws mockery and analysis. “Hindi film,” the novelist Amit Chaudhuri argued wryly in The Guardian in 2006, using an early term for the country’s mainstream cinema (hinged on the defining aspect of language), “is not an innocent genre,” unlike the films of Hollywood. Where the Western trope of the hero’s journey would have you believe that a person’s fate rests in their hands, Chaudhuri argues, Bollywood machinery pulls from a more ancient belief system, one aware that we have no control over our fates: “This doesn’t mean Hindi cinema is fatalistic — its exuberance is indispensable to its conviction that life is an unrecognizable rather than categorizable thing.” Offscreen, it’s time that forces us to realize the fact of this cruel grandeur, our puniness in the face of life’s whims, but “Bollywood reveals it to its audience [through] a series of devices: For example, coincidences, doubles, brothers separated at birth. These devices make the Hindi film embarrassing but also, at its best, very moving.” Om Shanti Om features several of these: Coincidences abound, but most strikingly, our two main characters disappear partway through the film and are reborn, now in reversed roles. Doubles, check. Rebirth, that supremely Hindu narrative device, check. Khan plays both a wannabe and, eventually, a superstar. He ends the movie, one could say, as himself. Padukone is now the upstart. All is right, in a sense, or at least, all is possible. Khan’s 360-degree abilities help make it so.

But if Hinduism is intrinsic to the Bollywood machinery, so, of course, is Khan — and the country’s many Muslim superstars and invisible artisans, past and present: a signifier of the essential pluralism beneath the country’s majoritarianism. Khan is unique in how he transmits this complexity. Before Om Shanti Om, there was Main Hoon Na, also with director Farah Khan, her first feature and their first partnership. That movie explicitly dealt with religious strife, with its buoyant envisioning of Indo-Pak relations. But in the cocoon of Om Shanti Om’s Bollywood, subversions are subtler. In one early scene, as the lovelorn Om Kapoor, Khan wears a flashy golden necklace, its bulky pendant etched against the triangle of skin exposed by a casually unbuttoned shirt. At first glance, the gaudy bauble looks cheap, set against Khan’s floppy-haired boyishness, a prop for an infantilized member of a boy band. In fact, it’s a marker of his canniness and intensity as an Indian public figure. The pendant is made of three symbols, suggestive of the country’s most populous religious groups: an Om symbol, a crescent with star, and a cross, commingling as they sometimes do on the backs of auto rickshaws and on the walls of shops. The pendant leaps from the screen, a betrayal, perhaps, of Khan’s, more than his character’s, preoccupations; like any smart service worker, he lets us know everyone is welcome to buy what he’s selling.

Or maybe that’s too crass an interpretation. In The Inner Life of Shah Rukh Khan, we see him on his off-hours, the politesse slightly loosened. He presents as an uninhibited, bone-deep Indian pluralist, if slightly limited in his embrace, to the largest of the country’s faiths. He organizes a Lakshmi puja with studio employees, eager for the fortune promised by the Hindu goddess of wealth. A later scene shows him at home with his wife and kids at an altar set up for Diwali. “Children should know about the value of God, whether it’s a Hindu God or a Muslim God,” he says, adding that a copy of the Quran sits beside icons of Ganesha and Lakshmi, and that he folds his hands in a namaskar position when his son says the Hindu prayer, the Gayatri Mantra, while elsewhere in the house, he might chant the Muslim invocation, Bismillah. “I’m not a great follower of religion,” he continues. “I believe in Allah very strongly, but I’ve never been forced by my parents to read the namaz five times a day.” In the Khan household, we learn, Eid, Diwali, and Christmas are all celebrated.

In the years since, he has continued his dizzying productivity, even as he’s ridden constant waves of disappearances and comebacks. He’s played antiheroes and darlings, dozens of Hindu characters but also, with time, Muslim ones, perhaps most famously, Rizwan Khan, in the 2010 film My Name Is Khan. That film, about a Muslim man with autism married to a Hindu woman, immigrants in America who respond to the hostile Islamophobia of the post-9/11 landscape by trying to meet the president, threw Khan into the path of India’s Hindu far right, namely the Shiv Sena Party, which demanded protests and boycotts of the movie after he spoke out against the passing over of members of Pakistan’s cricket team by the Indian Premier League. If he was stealthily Muslim before, he was no longer — his complexity as an Indian superstar extended on- and offscreen.

Last year’s release of Pathaan, a second blockbuster action movie, after Jawan, reunited Khan and Padukone (and stars John Abraham, who is Christian by birth) and again stoked ire. Members of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party called for a boycott and burned posters in the streets, their censure directed at the song-and-dance number “Besharam Rang,” or “Shameless Color.” Once more, Padukone and Khan only have eyes for each other. Only now we are in a fantasy so calculated there’s nothing fantastical about it: a seaside boardwalk in Spain, Padukone smoldering in swimwear. Business as usual for Bollywood. Khan appears in his latest incarnation — grizzled with a goatee, an elder statesman returned to the screen.

The notorious bit arrives at the end. Padukone wears a bikini in a shade likened by critics to the orange robes of Hindu ascetics as she writhes, an insult to Hinduism, argued the affronted. An offshoot theory cast Khan’s body under direct suspicion: His six-pack, naysayers insist (more sharply defined than ever), can’t possibly be real. Of course, it seems likely that it’s Khan’s onscreen embodiment of a national hero — he plays a Muslim character who is a gifted employee of the Indian intelligence agency RAW — that is the fiction under attack by the emboldened Hindu right of today. His own claims to Indian identity, as an “out” Muslim star, as well. Padukone’s tangerine sari of Dhoom Tana against his Om Kapoor never inspired rebuke. But Khan is ever capable, a man of his craft, a man of his country, and a man for many moments. On the press tour, in a mix of Hindi and English, he delivered a riposte that was also a reminder, as fetching as the reminiscences of Om Shanti Om: Deepika is Amar, I’m Akbar, John is Anthony. Not an obtuse reference, but a keen one, to the 1977 Bollywood film Amar Akbar Anthony, about three Indian brothers separated at birth and raised in different religious communities. A sleeker invocation, you could say, than the bulky pendant, and similarly, one only Khan, the chameleon, could pull off quite so winningly.