“He left behind his passwords. I think it was intentional.” When Mats Steen died at the age of 25 in 2014, his parents, Robert and Trude, assumed that their dear son, having spent the past decade playing video games from a wheelchair in the basement of their Oslo home, had missed out on pretty much all of life. Mats’s body had been ravaged by Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a rare and progressive disease without a cure, and the video games had been an early concession by the parents “since he was missing out on so much.” And as his body grew weaker, Mats played more and more, logging in around 20,000 hours in World of Warcraft. “Our biggest sorrow,” Robert says in Norwegian director Benjamin Ree’s powerful new Sundance documentary Ibelin, was “that he’d never get to experience friendship or love, that he’d never make a difference in other people’s lives.”

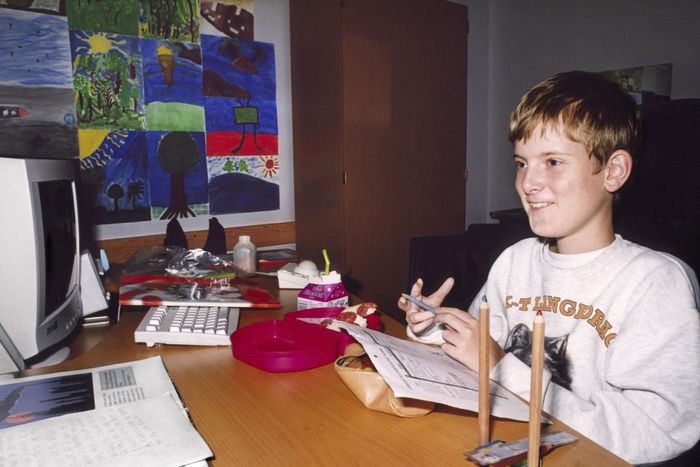

The peculiar genius of Ree’s picture is that it effectively tells Mats’s story three different times from three different emotional perspectives. Each movement of the film opens up a new world, and each is affecting in its own way. It all begins with the story we might expect: The tale of a bright young boy, diagnosed at an early age, wasting away from a heartless illness. Home videos, interviews with family members, uncomfortable parties, a terrified child throwing himself in tears into his mother’s arms — a slow and steady decline glimpsed in poignant footage. “All dreams go up in smoke,” we’re told. “All thoughts turn dark.”

After Robert and Trude update Mats’s personal blog with news of his death, thousands of emails pour in expressing condolences and love. Some send poems, songs, long essays, and remembrances. At first, the parents assume these are just random, anonymous well-wishers. Suddenly, however, Ree rewinds his film and tells Mats’s story again, this time using the young man’s own words from a blog he kept, voiced by an actor with a similar voice. The observations are funny, irreverent, heartfelt. Mats talks about missing out on the 1980s with its silly fashions and interesting music. He talks about being born the year the Berlin Wall fell and feeling like it was making way for him. He remembers hating summer camp and the humiliations of being taken to amusement parks (“Like some twisted, handicapped version of Prison Break”). And he talks about his computer games. “It’s not a screen; it’s a gateway to wherever your heart desires,” he observes. “I pump up the music and I leave this world behind.” Specifically, he goes to World of Warcraft, to a guild community known as Starlight, where his avatar is the strapping, muscle-bound Ibelin Redmoore, a beloved and popular private investigator.

And now, Ree drops the hammer. Using Starlight’s 42,000 pages of archived texts and commands — containing not just what was said but what was done and felt among the players and characters in Warcraft — he retells Mats’s story again, but this time via voice actors and animations that bring the adventures of Ibelin Redmoore to life. It’s a huge aesthetic gamble. Films that try to capture the qualities of virtual life often wind up unwatchable, an unpleasant hodgepodge of avatars and dodgy graphics. The animations in Ibelin are artful and not over-the-top. The figures do move in that stiff, programmed way that video-game characters tend to, but Ree makes their stiffness and their pauses meaningful; they move like they’re slowly learning to live in the world. We feel their trepidation, and we understand that behind these awkward avatars are real people, out there somewhere, longing to connect.

Telling Ibelin’s story also means telling the stories of others in the guild, because it turns out that Mats did indeed make a difference in people’s lives. So we meet Rumour, a.k.a. Lisette Roovers, a young woman from the Netherlands whose avatar had a romantic tryst with Ibelin and eventually became something like a girlfriend, even though Roovers noticed that the young man on the other end of the internet connection refused to meet or do any kind of video chats. We also meet another woman, Reike, a.k.a. Xenia-Anni Nielsen, who confided to Ibelin that she was having difficulty communicating with her autistic son. Ibelin suggested that she try to connect with him through the game, and so mother and child formed a bond online that eventually led to their coming closer in real life. Both Nielsen and her son are interviewed, and we see just how much of an impact Mats did in fact have on these lives.

Ree is a master of documenting the imagined possible, of lives half-lived. His previous film, The Painter and the Thief, told the long, fascinating story of an artist who befriended a man who stole her painting and with whom she forged a bizarre, near-romantic bond. The director understands a key truth about human nature: For almost all of us, the wished-for world always seems to lie just outside the bounds of our reality. We never get what we want out of life, but what we want never feels that far away. Watching Mats become Ibelin and fulfill a life nobody — not even he — thought possible is to watch someone give themselves over to a dream and find something resembling happiness.

Ibelin is an overwhelming film, ugly tears all the way down. It starts off with the most unspeakable of tragedies and then, as it winds its way back through Mats’s life, becomes a bittersweet story of empowerment, acceptance, even joy. Nielsen recalls that Ibelin was always running in the game, that he always entered Starlight with a big long run — understandable given that Mats had long ago lost the ability to even walk. By the time the film is over, we start to imagine that Mats/Ibelin is still there, either in the digital ether or somewhere else, running to his heart’s desire.

More Movie Reviews

- The Thriller Drop Is a Perfect Addition to the Bad-First-Date Canon

- The Accountant 2 Can Not Be Taken Seriously

- Another Simple Favor Is So Fun, Until It Gets So Dumb