Thirty-five minutes. That’s how long it took the most recent episode of HBO’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark to get back to what, on most true-crime series, would be the primary focus: the investigation of the series of burglaries, rapes, and murders committed in the 1970s and ’80s by the elusive Golden State Killer.

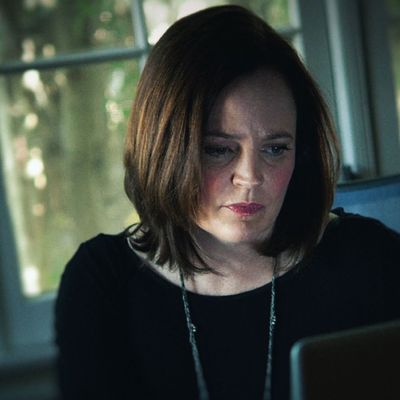

But I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, based on the best-selling book by the late Michelle McNamara, isn’t like most true-crime series. It’s true that it focuses on the decades-long search for a man who terrorized many and managed to avoid capture, something many similar series have done. But it’s also the story of McNamara’s obsessive interest in solving the case and the degree to which it consumed her mental and emotional energy, indirectly leading to her sudden death in 2016.

The first half of the penultimate episode, “Monsters Recede But Never Vanish,” which aired Sunday night, focuses fully on the aftermath of McNamara’s death, the factors that contributed to it, and how it impacted those who loved her, including her husband, Patton Oswalt. By attempting to piece together the issues McNamara was dealing with, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark tucks another detective narrative of sorts into the larger one it’s already unspooling. It also upends the traditional structures found in most reality-based and fictional procedurals, where the protagonists tend to be either suspected or wrongly accused criminals or the cops/agents attempting to apprehend them. (See The Jinx, Making a Murderer, The Staircase, Mindhunter, or pretty much every episode of every incarnation of Law & Order.) In I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, the protagonist is McNamara, and she serves a multilayered, simultaneous role as detective, victim, and, as a self-declared true-crime aficionado, a proxy for everyone watching this show and others like it. That last factor enables I’ll Be Gone in the Dark to interrogate the reasons why this genre is so enticing, especially to women, something that other TV true crime has rarely, if ever, done.

Women have a well-documented obsession with this type of storytelling. A study at the University of Illinois back in 2010 demonstrated that women are more drawn to true crime than men. Numerous articles and trends since then have supported the existence of this gender-based preference, including the fact that attendance at CrimeCon, the annual convention for the true-crime-crazed, skews heavily female. Footage from the 2018 CrimeCon is featured in the finale of I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, which airs next Sunday. When the camera pans the captive crowd during a panel, the sea of faces belong overwhelmingly to white women. (According to the New York Post, women accounted for 80 percent of attendees at CrimeCon that year.)

As I’ll Be Gone in the Dark makes clear, Michelle McNamara, who wrote the True Crime Diary blog in addition to her posthumously published book, counts herself among those women who are attracted to stories about rape and homicide, even though, more often than not, women are the victims in these narratives. “I had a murder habit and it was bad,” McNamara declares, via writing spoken by actress Amy Ryan, in the docuseries’s first episode. “I would feed it for the rest of my life.”

Her specific fixation on the Golden State Killer, a name she invented for the criminal once dubbed the East Area Rapist and the Original Night Stalker, took over her brain cells, bolstering her determination to play detective but also invading her subconscious. As “Monsters Recede But Never Vanish” explains it, the burden of sharing her headspace with a nebulous bad guy and his victims, coupled with the stress of trying to meet her book deadline, led her to take medications — Adderall, Xanax, and fentanyl — that caused her demise. (She also had an undiagnosed heart condition that may have contributed as well.) People within her inner circle, including her husband, were aware that she was under great stress but didn’t realize the extent to which the meds could be damaging her body. It seems safe to assume that McNamara herself didn’t even realize it.

The result is a loss that is sudden and devastating for Oswalt; their daughter, Alice; and everyone who knew and loved McNamara. Even though the feelings about her death stem from a completely different situation, the grief, the need for answers, and the questions about what could have been done to prevent this tragedy mirror the feelings expressed in the docuseries by the victims of the Golden State Killer. Even those who survived his attacks, several of whom speak in great detail about their experiences, can be described as still grieving. They may have been lucky enough not to lose their lives, but they still had the versions of the lives they once lived ripped away from them. That, too, is a type of death.

The attempt to suss out the things in McNamara’s psyche that may have contributed to her death inevitably dovetail with the things that may explain her attraction to true crime. This week’s episode refers to parts of her personal history that have been referenced in previous episodes, connecting them the same way McNamara so expertly connected bits of evidence. There’s the fact that McNamara was sexually assaulted by her boss years earlier, when she lived in Ireland; a tendency toward depression and addiction that runs in her family; and a fractured relationship with her mother that was starting to be repaired when McNamara’s mom suddenly died. The series never explicitly highlights this, but McNamara’s desire to be a good mother — expressed via her wish to spend more time with Alice and to possibly have a second child — surely added another layer of pressure on her that was exacerbated by the guilt that she had not been a good enough daughter.

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark posits that all these regrets and traumas were swimming beneath McNamara’s surface, much like the monster swims underwater, a few feet below a freestyle-stroking woman in the clip from Creature From the Black Lagoon that director Liz Garbus weaves more than once into the series. McNamara says she always sensed a darkness in herself that was capable of creeping in at any moment, and Garbus and her fellow directors, Elizabeth Wolff and the team of Myles Kane and Josh Koury, make us feel that with the recurring use of ocean waves that nearly overwhelm the camera lens and dark shadows that stealthily advance across suburban yards.

Most women watching this show will relate to some, if not all, of the issues with which McNamara grappled, including the need to self-medicate. Melanie Barbeau, a citizen detective who also closely tracked the Golden State Killer case, who acted as a source for McNamara and was a victim of sexual abuse, admits that immersing herself in those crimes may be its own form of self-medication.

“I think sometimes maybe living vicariously through other situations or dealing with this case, that it’s helped me forget my own traumas,” she says. In the finale, Karen Kilgariff, co-host of the My Favorite Murder podcast and a friend of McNamara’s, echoes this idea of true crime as an escape or form of therapy for women. I am by no means the first one to posit this theory, but I also think true crime provides women with a sense that justice will prevail, even though we know it often doesn’t.

The fundamental appeal of most true-crime shows, books, and podcasts lies in the expectation that we will get answers, at least on a basic level, that explain why something horrible happened, usually to a woman. Getting an answer — or at least believing that you got one — implies that there is still some reason in a world where women can be so haphazardly abused and victimized. Sifting through the gory details and photos from a crime scene in episodes one or two is a way to face that reality, with the knowledge that it will eventually be cushioned by learning the identity and motives of someone who could do something so terrible in episodes six or seven.

By the end of this week’s episode, when, in the middle of the tour for McNamara’s posthumously published book, Golden State Killer Joseph DeAngelo is finally taken into custody, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark provides that certainty. But it’s intertwined with the undeniable, unchangeable fact that McNamara is not here to see it, in part because she had a murder habit, it was bad, and she did feed it for the rest of her life.

“I wish you were pointing that camera at Michelle and not me,” Oswalt says in the last seconds of “Monsters Recede But Never Vanish.” “I hope they got him. I hope she got him.”

It’s the sort of moment that a true-crime fan relishes: The monster has finally been revealed and contained. But it’s also a moment that makes you think about how much was lost in the pursuit and whether you, too, have a murder habit that maybe you should feed a little less often.