When production designer Jack Fisk was in art school, he spent two summers with no electricity or running water in a friend’s small house in Vermont. He kept his groceries cold in the spring water that ran by the house and used a neighbors’ loaned horses to plow a garden. Fisk’s experience sparked his interest in how people of other places, times, and cultures lived, a curiosity that in turn served his decades creating the visual language of films like longtime friend David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, recurring collaborator Terrence Malick’s The New World, Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, and Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, for which Fisk received his third Academy Award nomination.

An adaptation of David Grann’s nonfiction book and a real story, KOTFM begins in 1919 and is set in and around Fairfax, Oklahoma, where members of the Osage Nation are being murdered by their white guardians, friends, and family members for their lucrative oil headrights, including the family of Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone). To understand the look and culture of the area, Fisk read period books like Maude Cox’s As It Was: A History of Osage County, Oklahoma; pored over photographs, maps, and county records; and did a lot of exploring on the ground in Fairfax, Pawhuska, and various nearby towns. Months later, Fisk built his sets grouped together in shared areas, creating “a sense of a real world.” He and the production-design, art-direction, and set-decoration teams ultimately used nearly 50 locations, some of which they built from the ground up (like Mollie’s house on the reservation and a train station) and others that they rejuvenated (including two blocks in Pawhuska that stood in for downtown Fairfax).

As the film traces the marriage of Mollie and Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), three exquisitely detailed sequences reflect the love and betrayal at the relationship’s core: their wedding on the Osage reservation, Ernest’s humiliation in the town’s Masonic Lodge by his Machiavellian uncle William King Hale (Robert De Niro), and a radio-play reveal that allows Scorsese to break the fourth wall. Each scene is packed with decorative details that reflect deeply investigated specificities of time and place and honor the Osage culture that endures despite the actions of Hale and his broad network of “wolves.” “I could see many films being made about Native Americans because there’s so much — the last 100 years, 200 years — that we’ve ignored or we’ve not wanted to talk about,” Fisk says. “You feel a sense of responsibility to portray it as realistically as possible. It becomes something more than just design.”

The wedding: “The Osage had great parties”

After Ernest moves to Fairfax, where his uncle Hale has business and personal connections to the Osage people, he starts driving for Mollie until the two fall in love and decide to marry. The film makes clear early on that the not-very-bright Ernest is under Hale’s thumb and that many of the Osage killed in town are victims of Hale and other white residents’ labyrinthine schemes to steal their oil headrights. Many white people throughout Fairfax have either married or befriended the Osage to be assigned as their legal guardians, and after killing them off, they inherit their fortunes. That tension is briefly put aside for Mollie and Ernest’s wedding sequence, a massive party for guests of both cultures at the home Mollie and her mother Lizzie live in on the Osage reservation.

Fisk and his team built the home entirely, making it slightly larger than scale to accommodate filming inside of it, as well as the Osage round house where ceremonies and important meetings took place and the cemetery seen in the distance. Lines of multicolored Pierce-Arrow cars, dozens of extras, a band, elaborate costumes for Mollie and her sisters, and tents housing Mollie and Ernest’s respective families and friends fill the set.

The wedding scene, Marty really wanted to do traditional. Ernest and Mollie probably didn’t have a wedding like that. Mollie had already been married to Henry Roan, who was Osage; if she was going to have a traditional wedding, it probably would have been with him.

The Osage had great parties, and they could go on for days. We put up tents, we had cooking outside, we brought a lot of people in and music. On the property is the summer house, the structure that Lizzie died in. At about the turn of the century, they started putting canvas on it because the United States military would give them canvas. In the yard, we built a little structure and brush cover for Ernest and Mollie to do their vows under, which is traditional. In the prairie, there weren’t many trees at the time; there were so many fires that they’d be burned down. We ended up taking trees out with visual effects because there were too many.

Costume designer Jackie West — who I’ve worked with on nine films — had done so much research and found out so many wonderful things. The bride and the bridesmaids are wearing coats from American officers from the time of Thomas Jefferson. When the Osage met Jefferson, they admired the officers’ coats, and Jefferson said, “Well, take off your coats and give them the coats.” But the Osage men were six feet tall and outdoorsy, and the coats wouldn’t fit them. They ended up giving them to their daughters, and they started using them for special occasions. This U.S. military jacket suddenly became a wedding dress for the Osage, and when those coats wore out, they would start making new ones with a similar pattern.

The Masonic Lodge: “I wanted to make it weird”

After Ernest and Mollie are married and he starts to enjoy her money, he begins scheming for more — without Hale’s permission — in increasingly foolish and attention-generating ways. To get Ernest back in line, Hale brings him to Fairfax’s Masonic Lodge, where Ernest’s brother Byron (Scott Shepherd) is waiting to help Hale dole out punishment. In a wonderfully bizarre sequence, Hale identifies himself as a 32nd-degree Freemason and then violently spanks Ernest with a paddle in a room decorated sparsely with Freemason portraits hanging high on the walls, a checkered floor, a potbelly stove, a podium at which Ernest kneels, and straight-backed wooden chairs. The scene’s chiaroscuro atmosphere is noticeably different from the rest of the film’s naturalistic feel, and reflects the lengths to which Hale will go to keep Ernest (and Mollie’s oil headrights) close.

I knew the First National Bank and Masonic Lodge building, and during an early visit to Fairfax, I went there to see it. In that bank there had been a museum that collected local memorabilia. An Osage woman, Danette Daniels, had bought the bank, and she let me come in. That first day, I found a 1925 phone book of Fairfax, and it had Ernest’s phone number and Hale’s phone number.

When I went into the Masonic Lodge, there were pictures of all the past and present members around the perimeter of the high wall. One of the first people I saw was Pitts Beaty, Mollie’s guardian. I found out another part of that building was offices, and those turned out to be the original offices of the doctors for Mollie, the Shoun brothers. I even found pictures of the exterior of that building from the period where the “Shoun Brothers” name was on the windows as advertising. Suddenly I knew we were making this film in the right place. We were able to fix up a little area around the building so we could shoot the exterior for some other shots, and we shot the doctor’s office in that building.

I always had an idea that Masonic halls were mysterious. Some were decorated to harken back to Egyptian tombs. The hall was white. It was about 100 feet long, 30 feet wide, and it had a carpet in it that was pretty decent. It had dark blue in it, and so I got this idea that if we painted the walls dark blue, then we wouldn’t have to buy a new carpet. I said to Marty, “I’d like to paint that Masonic Hall dark blue.” He said, “That sounds great.” And then I called Rodrigo Prieto, the cinematographer, and said, “I want to paint it dark blue.” And he goes, “That sounds great.” [Laughs.] A lot of times cinematographers go, “How am I going to light it?” because there’s not an excuse for much lighting. But there were some old skylights that had been boarded up, and Rodrigo was able to put lights up in those skylights, and I put yellow glass in, so a little bit of fill light came in from that. He put new bulbs in the practicals that were hanging in the hall, and the set decorators painted the walls dark, painted the white woodwork a wood color, and did a canvas of black-and-white checks, which is traditional for Masonic lodges. It instantly became a more mysterious place. We were fortunate that the members were all really pleasant people and they said, “Sure, you can paint it.”

It’s a weird scene in there. A grown man is paddling another grown man; it’s reminiscent of fraternities or some kind of club initiation. I wanted to make it weird, and we found paddles in there. We took the oldest portraits and we used them because you can’t really identify the people but you understand what they are. There’s a throne, almost, at each end of the room. There’s not much else in there; I don’t think there’s ever much in them. Generally my policy is not to put any more things in a place than necessary — the fewer things in there, the more you see the things that are in there, and if they’re chosen carefully, they can tell you about the character or the place or the story.

The radio play: “The only way you could end that story”

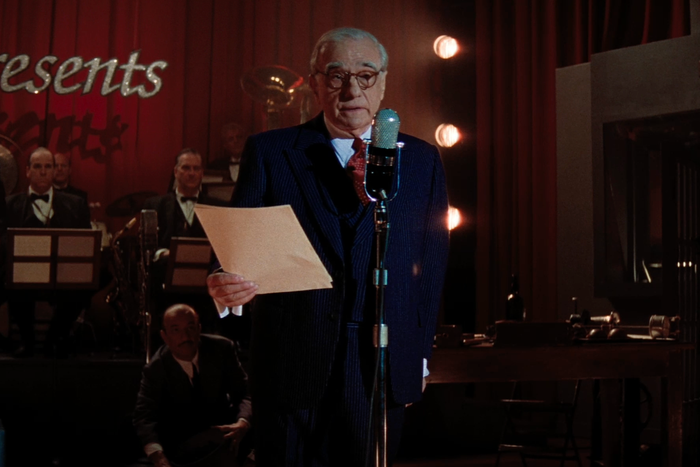

KOTFM is an adaptation of Grann’s same-named nonfiction book, which recounts the Osage murders primarily through the lens of how they helped lead to the formation of the FBI. The film’s penultimate sequence explains how popular knowledge of this gruesome and greedy period of American history is tied only to the FBI agents who “solved” the case via a flash-forward of a radio play recounting the murders. With onstage actors including Jack White and sound effects created with numerous contemporaneous gadgets, the scene starts by focusing solely on what happened to Ernest and Hale before Scorsese himself makes a cameo — in his high-school auditorium, where the radio play was staged — to tell us what happened to Mollie. With her story done, KOTFM ends with an overhead shot of present-day Osage drummers, singers, and dancers performing the now-Oscar-nominated “Wahzhazhe (A Song for My People)” in the round.

I don’t think the radio play was in the first screenplay, but it was in the script I read. Marty realized that he needed to have somebody come in as a moderator to explain stuff, but he said he didn’t understand exactly how to direct that person. How could he impart so much of the four years or five years of research he’d done into an actor? He decided to try it once himself, and he said in the middle of delivering those lines, he felt really comfortable and thought it was right. I think the radio show is probably the only way you could end that story, because it’s so sad — and then we have his oration of the story on top of that, and him being the director of the story makes it so powerful. By making this commercial FBI representation of the crime, it kind of makes us all accomplices — that we’re sharing in the monetary gains of the Osage’s suffering.

The plan before we wrapped was that we were going to shoot the radio station in a theater in Pawhuska. But as happens with a film, suddenly the days catch up with you and you have to go. Marty lives in New York, so that’s where we’re gonna shoot it. Meghan McClure, the supervising art director, supervised that. When we learned Cardinal Hayes High School was one of the potential radio-show locations, we said, “Oh, Marty used to go to school here. That’s where we’re gonna shoot.” And when Marty heard it was an option, he got so excited. He went to see three locations and he saw that one and went, “This is it.” It didn’t matter what it looked like. He grew up there, he’d gone to school there, and it just seemed like it should be.

Marty is a historian of everything that’s movie and radio, and we found a collector that had great sound-effect equipment. We found pictures of some of the radio stations in New York; they’d move around in legitimate theaters and put in a sound booth and an audience. We recreated that physically for him. We brought in the red velvet curtains, and we worked with Rodrigo on that because as he was shooting stuff, he wanted to make it brighter. We did the Lucky Strike sign, we brought in the chairs, we built the sound booth and put in the tables. We covered some speakers on the wall in the theater itself. The end of the film is so powerful, when it seemed like Mollie stopped fooling herself. I think in her mind, she wanted to have a way of understanding that Ernest wasn’t all bad. But it got to a point where it was over, and rather than us just sitting there with the sorrow of her life gone astray, Marty cut instantly to this thing that snaps you out of it and tells you more about how it’s remembered, in that sort of schlocky FBI way.

The last shot was the circle, with the camera rising up. We did come back to Pawhuska to shoot that. Marty already was excited about the film he put together, and he had that idea after he went to one of the circle dances they do in the round house. He wanted a way of including the present-day Osage into the film. During shooting, he read A Pipe for February by Charles H. Red Corn. That book described the opening scene in the film, where the Osage are burying their history, represented by this pipe, because they didn’t want it misused in the future. The thing that turned out to be so important was telling the story as well and as truthfully as possible for the Osage people. I don’t think it was a film made for the Osage people, but for the world, with all the Osage sensibilities as much as possible. We couldn’t have done it without the Osage help. The Osage wanted us to shoot in Oklahoma, where it took place. They wanted to be a part of it. And I think Native American cultures in our history have been so misrepresented so many times and been made promises so many times that they get tired of that. They didn’t want it to happen again with this story. And it ended up the right person got the film, and that was Marty, because he responded to that.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

related

- Every Oscar Best Picture Winner, Ranked

- 10 Things Sona Movsesian Could Do at the Oscars

- The Evolutions of Emma Stone