Carl Bar├ót beams into my laptop like a punk apparition from the Flying Dutchman, his dim room complemented by abstract paintings of women (ÔÇ£the artist was going to be the next Banksy, but it didnÔÇÖt happenÔÇØ) and vape smoke (ÔÇ£deliciousÔÇØ). IÔÇÖve never felt grateful for Zoom until this very moment.

ItÔÇÖs a busy time for Bar├ót, who has the fortune of starting off 2022 at the intersection of three significant musical endeavors: HeÔÇÖs touring as a solo act up and down England, planning more live dates with the Libertines, and preparing for a Dirty Pretty Things anniversary show. All that, and heÔÇÖs recovering from the effects of COVID-19, a stealth diagnosis that forced the Libertines to reschedule a few tour stops last month. ÔÇ£It has kicked my ass a bit. IÔÇÖm still feeling a bit like an endless hangover,ÔÇØ he tells me.

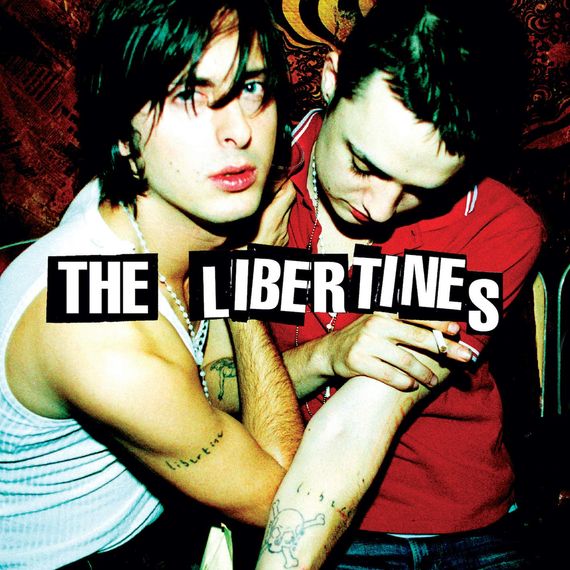

YouÔÇÖre probably reading this, though, because of the Libertines. Or at least for Bar├ót and Pete Doherty, whose affectionately acrimonious brotherhood fueled their self-mythology ever since meeting in the late ÔÇÖ90s. (Two other musicians, bassist John Hassall and drummer Gary Powell, round out the band but will eternally be relegated to Peggy status.) Together, the ladsÔÇÖ poetry ÔÇö a beguiling mixture of nostalgia and fantasy with a dash of patriotism ÔÇö and guitar riffs conjured the early-aughts indie-rock triumphs Up the Bracket and The Libertines and later their 2015 reunion album, Anthems for Doomed Youth. Bar├ót, 43, looks back at this era with equal parts awe and appreciation, almost as if he was able to steer his ÔÇ£good shipÔÇØ back to port without perishing at sea. HeÔÇÖs not exaggerating. ÔÇ£From my view,ÔÇØ he said between puffs, ÔÇ£I thought everyone would be dead.ÔÇØ

Best Libertines song

I guess it would be ÔÇ£What a WasterÔÇØ in terms of encompassing a lot of the Libertines ethos and mantra at the time, and starting out and how we saw the world and what weÔÇÖre about. Although, in an ideal world, thereÔÇÖd be different songs for different periods of our long odyssey of a journey. But yeah, itÔÇÖs ÔÇ£What a Waster.ÔÇØ Paul Weller recently quoted it as having his favorite lyric: ÔÇ£The cityÔÇÖs hard / the city fair.ÔÇØ I think thatÔÇÖs brought that back to the forefront of my mind. ItÔÇÖs about the struggle of fitting in with the world and then being accepted for being a dreamer, and that being okay. And the other connotations for usage of drugs and alcohol. It was just a maelstrom of that time ÔÇö finding out who you are and entering out into the world. The reason itÔÇÖs not on Up the Bracket and came out separately is because I didnÔÇÖt want my grandmother to hear my swearing. ItÔÇÖs ridiculous.

Most anthemic Libertines song

ÔÇ£Time for HeroesÔÇØ is the real sort of crowd-rousing one that makes people feel united in a purpose. In that sense, itÔÇÖs anthemic. But that song hasnÔÇÖt really got a chorus, which is quite unusual. IÔÇÖd say thatÔÇÖs certainly the rabble-rouser of our songs. I think it was quite evocative to write ÔÇ£Did you see the stylish kids in the riot?ÔÇØ I think everybody feels at times that they are the stylish kids in the riot. So theyÔÇÖre sort of bound together, almost politicizing without politics, just in a feeling that people seem to need. I played it the night before last, and the crowd went wild ÔÇö abandon ensues.

Song that will always remind you of Pete

The obvious answer is ÔÇ£CanÔÇÖt Stand Me Now.ÔÇØ Because if I played that on my own and sang both parts, it would be a bit strange. Like IÔÇÖm saying I canÔÇÖt stand myself. Which, on occasion, could be true. [Laughs.] Every Libertines song is so entrenched in our relationship. ÔÇ£CanÔÇÖt Stand Me NowÔÇØ is the obvious one. We both work so hard and connect in such a deep place when we write songs together that heÔÇÖs always present in my mind. And when we werenÔÇÖt together, when I was in Dirty Pretty Things and he was in Babyshambles, we used to cipher messages in our songs in the way that Persian lovers making rugs would encipher messages to each other. So we were never far from each otherÔÇÖs minds, even then. I donÔÇÖt want to give too much away, but there might be some messages to Pete in ÔÇ£Bang Bang YouÔÇÖre Dead.ÔÇØ I mean, in one of his songs he goes, ÔÇ£And if youÔÇÖre listening on the radio, I hope you know you broke my heart.ÔÇØ There are things like that. There are a few out there. I donÔÇÖt want to break up the romance. I got to keep them as ciphers.

Most ÔÇÿlandfill indieÔÇÖ career misstep

Did I ever make any indie landfill? I donÔÇÖt think I did. No oneÔÇÖs ever really going to see their work as landfill, which is why itÔÇÖs such a pejorative term. I guess there were some songs on the Dirty Pretty ThingsÔÇÖ second record that I listen back now and go, Shit, I didnÔÇÖt actually finish writing that lyric. IÔÇÖm just singing fucking nonsense. ThatÔÇÖs as close as IÔÇÖd say to indie landfill. But, I mean, thatÔÇÖs assuming indie landfill is about not caring what youÔÇÖre putting out. I think itÔÇÖs more about putting out the same chords or not putting any originality or effort into something. I may be guilty of many things, but I donÔÇÖt think not putting everything into crafting and dynamics, apart from the example I just mentioned, is something IÔÇÖm guilty of. In my personality, IÔÇÖm guilty of many things, but thatÔÇÖs for the therapist.

Libertines song you wish you sung

ÔÇ£Time for Heroes.ÔÇØ I always find that my mouth starts moving along when IÔÇÖm playing guitar. I go, Damn it. But itÔÇÖs quite confusing, because, obviously, when I play on my own solo gigs, I play those Libertines songs as well. And then when I go back to the Libertines, I occasionally I grab the mic when ÔÇ£Time for HeroesÔÇØ starts, and Pete will be like, ÔÇ£What the fuck are you doing? Get off, this is my bit.ÔÇØ [Laughs.] But then Pete was very kind in letting me have ÔÇ£What Katie Did.ÔÇØ So, you know, fairÔÇÖs fair. ThatÔÇÖs the thing about being in a band with two singers. You canÔÇÖt sing them all, can you? ThereÔÇÖs no democracy involved with who sings what song. ItÔÇÖs usually just whoever wins the argument, really. ThatÔÇÖs the reason weÔÇÖve got two front men in the first place ÔÇö┬ábecause neither of us was going to let the other one be the front man.

Dirty Pretty Things song that shouldÔÇÖve been a bigger hit

Theres one song called Blood on My Shoes on the second record, which I really loved, and no one seemed to like it, even now. People just hate that song. But for me, I really put blood into that song. I really gave it everything, and I loved it. Maybe it sounded derivative. But sometimes the derivative way is the best way of  like when Abbey Road came out and someone asked John Lennon why the lyrics arent deep in I Want You (Shes So Heavy)? And he responded to the effect of, Well, when youre drowning, you dont say, Excuse me, would you be so kind as to throw the life preserver and help me? You just scream. It was a bit like that for me.

Most autobiographical song

Its a tough one. Something like Anthem for Doomed Youth comes to mind, but the images the Libertines use are quite esoteric and escape-y as opposed to being directly about the day-to-day life were living. So Ill say Hippys Son from the second Dirty Pretty Things record. At the time, I was very conflicted and pushing back against my  I was sort of rebelling against the idea of being brought up as a hippie. That was a sort of primal scream of rebellion of the self. Thats one of Petes favorite songs, bizarrely.

Most agonizing album to record

It was The Libertines. We were thrown together hating each other. We each had six-foot-four security guards to protect us from each other, and we still had a fight on the first morning. The guards realized quickly that we werenÔÇÖt joking ÔÇö to stop us fucking tearing chunks out of each other and to stop all the dealers coming in and all that shit. It was a pretty, pretty hairy time. It was no joke. It was a very hard record to make. You could chuck all sorts of rock-and-roll clich├®s into the abandon that went on and all the lashings that happened. There was genuine danger there. But then love and hope and a lot of hurt. A lot of hurt. It came out of a very toxic time in our lives.

But as was the nature of  as was our wont, we had to show. We had to record an album. We had to make the music. Whatever was happening, that was so important to us. But it was a toxic time. I guess a lot of that came out on the record. I mean, God, it wouldve been a very different record if wed all rehearsed it for six weeks and then came in and played it all happily. Who knows what record that wouldve been. But right now, right then, with our struggles with each other, we just wanted to give the truth through song and music and work out what that truth was through doing it.

The truth was that these two young men, who came from backgrounds of turmoil, deeply wanted goodness and love and hope and were pretty fucked up and were fighting through that. It was a struggle. Ultimately, in coming together and not, well, killing each other, Pete and I managed to create something long-lasting and important to both of us. And hopefully other people too. To see that it still has some of that impact suggests that the record has done well.

Defining guerilla gig

The best ones, and the reason that they made such an impact, were the ones that we did in our front room in our flat. It was the time and at the sort of age where you didnÔÇÖt really care that much about everyone just ruining your flat. We used to let everyone take a book home with them. The internet had just become a thing. We couldnÔÇÖt believe that if we typed something into our computer, people would see it and turn up and we would have an actual, tangible response. It was a pretty groundbreaking time, really. One day we were just like, ÔÇ£Well, why canÔÇÖt we invite everyone around here for a gig? Save us going out and doing all that, the usual shit.ÔÇØ So we did that. Then we started doing it quite regularly, and it became a thing. One of the last ones, the police came in to bust the place. WeÔÇÖre playing in our kitchen and they go, ÔÇ£Whose house is this?ÔÇØ Me and Pete both pointed at each other exactly the same time. That was the halcyon age of the so-called guerilla gig. ThatÔÇÖs the one that sits in my mind the most. But back then we played anywhere. WeÔÇÖd play in peoplesÔÇÖ bathroom cabinets if they let us.

The idea was something that wasnÔÇÖt very common at the time. Looking back, now that IÔÇÖm a bit older, I can see thereÔÇÖs a lineage of that sort of thing. The Clash sort of had that ethos. But everyoneÔÇÖs equal, everyoneÔÇÖs the Libertines, everyoneÔÇÖs in the band. That was very much the feeling. EveryoneÔÇÖs welcome on the stage and everyone who wants to express themselves could get up and do it. That was perfectly plausible then. ThatÔÇÖs what we did. The fact that half of our gear got nicked every time we played wasnÔÇÖt really an issue. I think it was a real pleasure to experience and be a part of the freedom that came around then. I mean, right now, IÔÇÖd get some real shit if I brought everyone around to my house. EveryoneÔÇÖs going to know where you live. IÔÇÖve got kids. You canÔÇÖt really invite all the fans around to your house with your kids, can you?

Most enduring aspect of Libertines mythology

I think it was the belief in love and the togetherness that we all had. The fact we clearly loved each other very deeply. The fact that we shared everything. I mean, you could say we aired our dirty laundry in public. People really bought into that, and we did it on record as well. We really opened ourselves up. There was no privacy; we had gigs in our flats. Our breakup was very public, and we sang about it together. It was just so inclusive for everybody. I think thatÔÇÖs what people hold on to. So in terms of mythology, we had that covered with our Arcadian manifesto, with Albion being our vessel and Arcadia being our destination. I think thereÔÇÖs quite a lot to buy into with that. I still feel like that now.

How your definition of ÔÇÿAlbionÔÇÖ has evolved over the years

I think the good ship Albion has become a greater vessel, and there are a lot of people onboard. Inevitably family. Its still strong and, remarkably, we are still together after 20 years, when it really looked like  Well, from my view, I thought everyone would be dead. There wasnt a hope for us getting this far, and were about to celebrate our 20th anniversary. Weve built this amazing place. We built the brick-and-mortar embodiment of our dream. Its had to become more practical to sustain a family and to still have those dreams and to deal with all the normal shit that you have to have if you want to live beyond 27  which I realized on my 28th birthday I was going to be in for. So its now about a little bit more than just being on a boat. Maybe its about docking and establishing this so-called land, be it or not in Arcadia. Its funny how it always goes back to maritime imagery. Being a bit older and wiser, its making something that other people can live in, too, and encouraging people to create and be alive.

ItÔÇÖs timeless. ItÔÇÖs human nature to be drawn to the sea chantey. ThereÔÇÖs a metaphor for everything you can encounter. From great white whales to sirens to rum to a lot of rum to keel-hauling and lashings on the deck. And nice things, too. I think touring is very much like being at sea. With the bus, itÔÇÖs more like a submarine. YouÔÇÖre just there with your crewmates, popping up at random locations or ports. Sorry, I heard myself now. IÔÇÖm sounding like a bit of a knob. [Laughs.] Anyway, thereÔÇÖs hopelessness and hopefulness. When youÔÇÖre at sea, it can all end. ThereÔÇÖs yearning and longing. But then when youÔÇÖre there at sea, you romanticize everything in life, on land, in the past and future. IÔÇÖll be overthinking that for the next few days.

Worst advice you received from a rock predecessor

Well, heÔÇÖs not so much a rock predecessor, but this has stuck with me through the years. Once I was playing in the Bowery Ballroom with the Libertines. Damon Albarn came backstage and he said, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a great gig, great gig.ÔÇØ Then he basically told everyone to fuck off out of the room and cornered us and said, on our own, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a great gig, but youÔÇÖre not rude enough to your fans. You need to be a lot ruder. You need to really fucking tell them off.ÔÇØ Which is a strange piece of advice. Maybe it was some kind of sabotage he was planning there. Maybe he felt threatened by our rise. I donÔÇÖt know. ThatÔÇÖs the most bizarre thing that springs to mind when it comes to bad advice. I didnÔÇÖt follow it, of course. It might have skewed our manifesto a little bit.

But as the opposite, Mick JonesÔÇÖs advice was always fucking good. I donÔÇÖt know if IÔÇÖve actually managed to heed it properly yet. He told me, ÔÇ£When youÔÇÖre in an era of success, just enjoy it. Live in the present and enjoy it.ÔÇØ Mick was saying that 20 years ago. Long before all the wellness memes were coming out. [Laughs.] He was so right. Occasionally, IÔÇÖll stop and go, Fuck. LetÔÇÖs look at the good parts of it. ItÔÇÖs a whole yin-yang thing. Whatever bad part youÔÇÖre living in, thereÔÇÖs always a mirror good part. You just got to tap into it, whatever is happening.

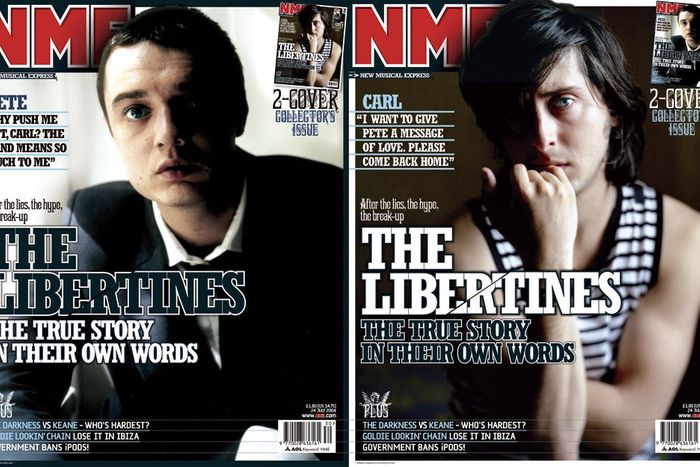

Favorite NME cover

They were like agent provocateurs, knowing all of the fractiousness of our relationship. In the height of our turmoil, NME did a special edition. They did two covers. One of me and one of Pete. They told me mine sold more, but they probably told Pete the same. ItÔÇÖs me looking all broken and alone in a Breton stripe jumper. I think thatÔÇÖs my favorite one. We must have been good for NME for that amount of time because otherwise they wouldnÔÇÖt have kept running us, would they? ThatÔÇÖs all right. One day, IÔÇÖll compile them all and make a wallpaper out of them for the toilet or something.

Legacy of the ÔÇÿlibertineÔÇÖ tattoo

I guess thereÔÇÖs a bit of cognitive dissonance in that itÔÇÖs about freedom and individuality, but everyone gets one. I think itÔÇÖs a reminder, for me, about freedom and liberty. ItÔÇÖs not about being dissolute. Freedom always exists within me, and I can connect with other people it exists with. Maybe thatÔÇÖs why a lot of people, especially in England, have it and can recognize a bit of a union in that. We did our own festival in Margate, and we had a tattoo tent giving free ÔÇ£libertineÔÇØ tattoos, so we might have flooded the market there. There were queues all day. But I still manage to, whatever mood IÔÇÖm in, summon up the appropriate level of gratitude and respect for people who get them ÔÇö because there are a lot of them. I mean, some of them are really badly done. Like, theyÔÇÖre barely legible splodges. I feel somehow guilty when I see those ones. I see them in some interesting places as well. Bizarre places people get them. But itÔÇÖs still a lovely thing.

More From The Superlative Series

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music

- Cyndi Lauper on the Freest and Most Provocative Music of Her Career