As soon as Dahmer ÔÇö Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story debuted last month, it became the most-watched show on Netflix: The streamer says Dahmer had one of the biggest launches in its history. But the limited series invited an array of criticism that came in swift and strong, much of it focusing on one central question: Why tell this grisly story again?

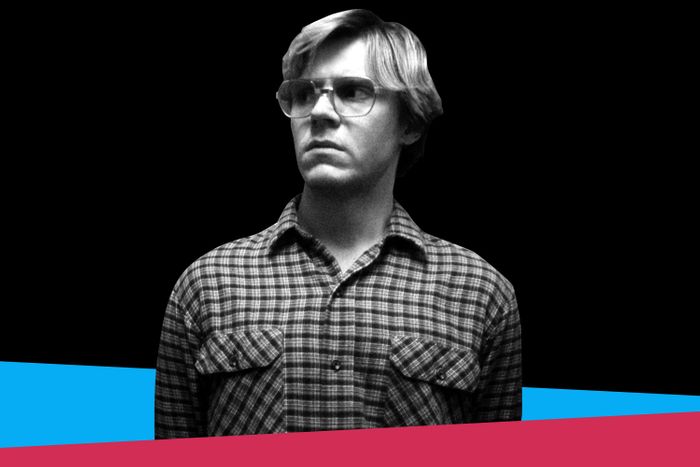

Evan Peters, who plays the serial killer, told NetflixÔÇÖs Queue that co-creator Ryan Murphy had a guiding rule: The show ÔÇ£would never be told from DahmerÔÇÖs point of view.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs a nice idea, considering the particulars. Dahmer killed 17 people between 1978 and 1991, and the majority were queer men of color. The thinking is that Dahmer got away with his crimes for so long because law enforcement in America rarely cares about those types of victims the way it cares about, say, white women.

But in practice, the stories of DahmerÔÇÖs victims arenÔÇÖt centered enough. Critics are saying that. Families of the victims are saying that. Having watched some of the series, Into It podcast host Sam Sanders is saying that too. This week, he spoke with our TV critic Jen Chaney (who wrote our Dahmer review) about the responsibilities a true-crime series has to its viewers, to the real people affected by these crimes, to marginalized communities, and to the true-crime genre itself. You can read an excerpt of their conversation below and check out the full episode wherever you get your podcasts.

Into It

Subscribe on:

How much of this new Dahmer show have you watched?

All of it.

Oh, thoughts and prayers.

Thank you. I took one for the team on this.

You really did. ThatÔÇÖs heavy. I want to talk about the central question facing this series: Who is it centering? Is it Jeffrey Dahmer, who is played by Evan Peters? Or is it, as Ryan Murphy indicated, primarily centering the victims of color who died at Jeffrey DahmerÔÇÖs hands?

Ultimately, Jeffrey Dahmer is being centered more often. But thereÔÇÖs an episode that is focused on Tony Hughes, one of DahmerÔÇÖs victims, who was deaf. And they really do try to shoot that episode more from his point of view, even to the point of having the audio drop out so youÔÇÖre seeing the world ÔÇö and not hearing the world ÔÇö in the same way that he would have. That was the best episode of the whole series because they actually did what they said they were going to do here: The whole first 15 minutes of that episode is just about Tony and his life before he even met Dahmer.

We should point out that the episode was written by Janet Mock, a black trans woman who has been working with Murphy for some time now.

ThatÔÇÖs right. ThereÔÇÖs also an episode thatÔÇÖs a little more centered on Niecy NashÔÇÖs character, a neighbor who is constantly telling the police to do something about this guy. And they do focus on his father a little bit. But itÔÇÖs very much JeffreyÔÇÖs show. I mean, it says ÔÇ£DahmerÔÇØ twice in the title.

IÔÇÖve watched Ryan MurphyÔÇÖs stuff forever and I like some of it, but his whole shtick from Nip/Tuck to now has kind of been glorifying pretty white men and the nasty things they do. Could Ryan Murphy ever have made the best version of this show and this story?

One of the reasons weÔÇÖre here having this conversation about these kinds of shows is because of another show that he made several years ago, American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson. That was a show where I was like, I donÔÇÖt need to see this. I know this story. But it surprised me how good it was, how it allowed us to go back and look at how different people were treated during that whole saga and see it in a new light. It was so good in that regard ÔÇö and also successful with Emmys and viewership ÔÇö that heÔÇÖs continued to do this, to revisit true stories and try to dramatize them. But he makes so many shows that itÔÇÖs hard to do any of them consistently well.

Are there other true-crime shows, scripted or otherwise, that do better on these kinds of issues of visibility and who is centered? What shows do this right?

Well, one that immediately comes to mind is a show called Unbelievable. It came out on Netflix in 2019; it casts Toni Collette and Merritt Wever playing detectives looking at a series of rape cases based on actual cases. They just take a completely different approach to talking to somebody after theyÔÇÖve been traumatized, and that show is just terrific at illustrating how often women are disbelieved in these kinds of situations.

Another one is IÔÇÖll Be Gone in the Dark. This is actually an HBO documentary about the Golden State Killer based on Michelle McNamaraÔÇÖs book. She passed away while she was working on it, so the show tracks what happened to her and her Golden State Killer investigation. Ultimately, the work she did in that book helped to finally apprehend that guy after decades. But she was under so much pressure writing the book that she was taking medications, mixed the medications, and died.

Oh my goodness.

So itÔÇÖs like these two things on parallel tracks, but then itÔÇÖs also interrogating what happens to your brain when you get immersed in true crime.

Family members of some of DahmerÔÇÖs victims have spoken out against the show, complaining about not being contacted as this show was being created. Most of the reviews acknowledge the central problem that you and I are talking about. If you had to give some mandates out to creators making true-crime content, which three golden rules would you give them?

One golden rule is: At every turn, do we need to show this? Do we need to do this? ThereÔÇÖs a whole sequence in Dahmer where they show people giving their impact statements about how what he did affected them. And thereÔÇÖs the sister of a victim who just starts yelling at him. YouÔÇÖve probably seen it posted side by side with the actual video from when it happened. And to me, thatÔÇÖs like, Now weÔÇÖre cosplaying reality. The womanÔÇÖs name is Rita Isbell. ThatÔÇÖs the real woman who was portrayed in the show.

And she has complained about this show herself since it came out.

She has. SheÔÇÖs one of the people who said, ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt know this was going on. Nobody cleared this with me. And next thing IÔÇÖm kind of a meme.ÔÇØ DonÔÇÖt re-create things shot-for-shot.

Rule No. 2: Acknowledge the impact that true crime has. ThereÔÇÖs some hand-waving in that direction with Dahmer. ThereÔÇÖs a point where Tony HughesÔÇÖs mother is suing the Dahmers because DahmerÔÇÖs dad wrote a book, and this lawyer is like, ÔÇ£All the victimsÔÇÖ families should be getting any profits from movie rights and book rights and so on.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs this idea presented that itÔÇÖs sort of ghoulish to do this, but it doesnÔÇÖt acknowledge that the show is doing it too.

I would say stop making the killers hot. ItÔÇÖs weird.

Ted Bundy was a decent-looking guy, but you donÔÇÖt have to make him Zac Efron, either.

These shows, and Ryan Murphy especially, do this thing where they introduce someone who is supposed to be a villain, who is supposed to be the bad guy, but then they confuse you by not just letting them be beautiful but focusing on them visually in the show in ways that kind of highlight their beauty.

He doesnÔÇÖt have to have a shirt off quite as often as he does in the show. But as weÔÇÖre talking, thereÔÇÖs another Jeffrey Dahmer documentary thatÔÇÖs going to drop on Netflix.

Please, no.

ItÔÇÖs very similar to a few years ago when Netflix dropped a Ted Bundy documentary and then streamed that Zac Efron movie about Ted Bundy in close proximity.

So rule No. 3: Netflix and others platforms need to not do that.

All of this raises a larger point: It feels like true crime is everywhere these days. Are we in a moment of peak true crime, Jen? Or has this stuff always been there, going back to Unsolved Mysteries days?

This stuff has always been there to some extent. As I was thinking about Dahmer and coming on here to talk to you, I was remembering this miniseries from way back in the ÔÇÖ80s called Fatal Vision, which was based on the book about this military veteran who allegedly killed his whole family but claimed he was innocent. And that was decades ago ÔÇö thereÔÇÖs always been some element of this. Eight years ago, this trend was really kicked off with the success of the podcast Serial, the success of HBOÔÇÖs The Jinx, and the success of NetflixÔÇÖs Making a Murderer. All of those shows and podcasts happened in really close succession, and I think that really kicked off this wave of true crime that has never ebbed at all.

I had forgotten about Making a Murderer. That was a moment.

Yeah. I honestly thought before Dahmer dropped and started really getting watched, This is going to be the tipping point. People are going to be like, ÔÇ£This is too much.ÔÇØ And I was dead wrong.

Why is that the case? It has to go back to money: Is it cheaper to make than other stuff?

Some true crime, certainly the documentaries, are not as expensive to produce as a scripted series might be. But when we think about studios and platforms relying on their IP, we think of Star Wars, we think of Marvel, we think of franchises that they just keep building more stuff around. And the reason is they donÔÇÖt have to explain to you who Spider-Man is. You already know. So that part of the marketing is already done for you. Serial killers are IP. ItÔÇÖs a horrible thing, but itÔÇÖs true. People know who Jeffrey Dahmer is. They did no promotion. They did not give critics screeners in advance. There was a trailer and then, a few days later, it was on Netflix. And if you turn on Netflix and you see Dahmer on your home screen, youÔÇÖre like, Oh, I remember that case.

How do I leave this chat feeling in any way optimistic about the state of the stuff that weÔÇÖve talked about?

IÔÇÖm going to say you donÔÇÖt. You leave feeling pretty shitty about it. There are good ways to do this ÔÇö I feel like there are creators who can do it with some sensitivity ÔÇö but I donÔÇÖt think we need the marketplace to be flooded. And unfortunately, if people keep watching this stuff, Hollywood is going to keep flooding the marketplace with it.

This interview excerpt has been edited and condensed.