At a sold-out Bowery Ballroom on Friday night, fans were stressed. They had been reading the news. Drowning in it. They’d made a separate group chat to keep the headlines away from the joy. They were watching Maddow and reading the AP for 20 minutes daily before law school. They were still reading the Times, however sheepishly; a leather-jacketed Hobokenite had the day’s full paper edition under his arm. Or they had traded their subscription to the Grey Lady and the rest of the American “legacy media horseshit” for the BBC and the Guardian. They were trying to take a step back from the updates. They were evangelizing about Heather Cox Richardson and Jamelle Bouie. They were streaming Hasan Piker on their boss’s dime every damn day.

They were still on X, but they were verifying their sources. They were considering running for county committee and getting back into organizing. They were studying all 1,249 pages of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. They were cybersecurity journalists, lawyers defending climate scientists from political censorship (work lately? “a nightmare”), and federal workers wondering about their jobs.

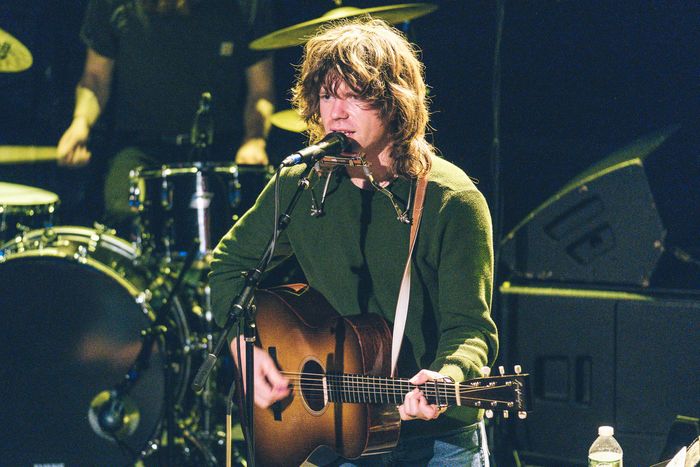

Onstage, just a 30-year-old guy and his acoustic guitar, was Jesse Welles, his shoulder-length Jim Morrison locks about scraggly as his voice. Wearing jeans, a green crewneck, and an enormous grin, he launched into song after song of, well, more news. Hours earlier, about a dozen blocks away, Luigi Mangione had appeared in court, charged with assassinating the CEO of UnitedHealthcare. Fingerpickin’ under the lights, Welles sang about the company’s business model — one of his most popular songs: “You paid their salary to deny you what you’re owed / There ain’t no ‘You’ in UnitedHealth.” He warbled about the war in Gaza as an attempt to clear the Strip and turn it into resorts, and the crowd joined in, turning it into a pub anthem. Football-match chants of “Jesse! Jesse! Jesse!” echoed between songs. He ran through tunes about processed foods, whistleblowing at Boeing, fentanyl, Elon Musk. There were titterings of weary laughter and the occasional solidarity fist in the air.

A mix of old-fashioned folkie signifiers and trending-topic populism, delivered in hooky snippets on social media several times weekly, has taken Welles from obscurity to 2 million followers across TikTok and Instagram in under a year. In most of his clips, he croons and strums in front of an Arkansas field or a rural stretch of power lines. (During one number, an attendee shouted, “Why didn’t you film this one in the woods?”) He has churned out dozens of viral songs pegged to current events that deliver clear-eyed opinions in “a concise and consumable way,” as Jessica, a 25-year-old Long Islander, put it. Which is to say that he’s followed the influencer playbook of dropping a steady stream of commentary on what’s already being talked about — but with four chords and Wikipedia-mouthed wit.

It’s probably helped that Bob Dylan has been in the air, in no small part due to last year’s biopic starring Timothée Chalamet. Welles gets Dylan comparisons all the time owing to his rough-hewn vocal grain, the harmonica propped up around his face like orthodontic headgear, and a young Bob being the average person’s main reference point for wordy folk music with a bent toward social commentary. More than a dozen concertgoers told me they grew up on Dylan. For a duo of 24-year-old north Brooklyn Matts attending the show together, Dylan had led them to Welles. Ginger-bearded Matt, in a thrifted jacket featuring a map of local TV news stations, was going through “a big Bob Dylan phase,” so Tall Matt recommended Welles. Tall Matt had been on a Bob Dylan kick of his own, “and then I just really got into Jesse. He introduced me to John Prine and got me into a lot of older folk music.” One of Welles’s songs borrows the violin part from Dylan’s protest song “Hurricane,” and the Bowery show featured a speedy cover of his “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” The set also included renditions of the Velvet Underground’s “Sweet Jane” and “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” by CCR, but his own songwriting consistently drew the most enthusiastic response.

A 26-year-old named Sierra told me they listen to a lot of folk music, “but I think a lot of folk that talks about more political stuff is older, like from the ’60s,” they said. “This feels like the start of something new again in this genre, and hopefully further out past the genre.” Their friend Shomari, a 31-year-old in a beanie and glasses, noted how much more common it has been for rappers to deal in specifics about the things happening in the present: “Kendrick, a lot of those guys — they’re all talking about the same stuff. This is just kind of a different font.”

“Jesse’s music has an absurdism of the American people who, since the end of ‘the End of History’ in 2020, have realized, Oh my God, the state of things is so obviously not anything that anyone would want,” Johana, a 26-year-old from Bellerose, told me. “It captures the futility of the moment.” In the 2024 general election, she wrote Joe Biden in as a fuck-you vote. “That’s what they deserve.”

Deborah, a 70-year-old who had flown in from a suburb of Rochester, spoke about Welles as if spellbound: “He’s the light in the darkness.” She had been surprised with tickets by her son-in-law, Ben. As they rested on a couch in the bar below the venue after the show, she was still in a daze. “I feel like I’m in The Twilight Zone because I love him. I had a bad year in some ways with my health” — she had broken her hip — “and my mom died last year. But every morning and every night I would listen to his songs. He’s on my feed and I just suck it up.”

@jessewelles united health is streaming everywhere #sInGerSoNGwrIter #OrigInaL #COunTrY #folk #peace

♬ original sound - Welles

Many of Welles’s fans told me they are into other artists they see as political, citing Rage Against the Machine, System of a Down, riot grrrl, punk, and other folk. But a few said they typically stay away from music they view this way. “It works for me in this context because I find his lyrics to be really clever” — it’s hard not to smile at lines like “Monsanto Claus delivered all the cancer in your ass” — “and you can still enjoy the music without hearing the political side of it,” Megan, a 24-year-old journalist, told me. “Although I do tend to agree with a lot of his politics.” (She places herself “on the left.”) Marin, a 37-year-old with socialist views, attending with her boyfriend, said that unlike most political music, Welles’s gets a pass because “it seems a lot more authentic. It’s just one guy singing from the heart.”

When seemingly organic virality turned the unknown Oliver Anthony’s “Rich Men North of Richmond” into an overnight Billboard No. 1 in 2023, it was a premonition of Jesse Welles: a tree-backed video of a red-hued man from the rural South strumming an acoustic guitar and singing about elites’ depredations on the poor and working class. But where Oliver’s ire extended to regular people — “the obese milkin’ welfare,” for example — Welles tends to keep his sights trained on corporations and the rich and powerful. And while he hasn’t shied away from political lyrics (including anti-Trump ones), his songs usually live in the realm of complaint or implication, allowing people with disparate party allegiances to embrace his music. On Welles’s Instagram, you can find Glenn Beck simping in the comments and avowed fans claiming to be Trump voters.

Nonetheless, this was a mostly white room full of Kamala voters with a few Gaza-motivated abstainers mixed in. The most surprising thing about the crowd was the number of middle-aged people there to see their favorite TikToker alongside all the 20- and 30-somethings. They were lovers of NPR and The Daily or the Marxist Rev Left Radio. Nobody mentioned America’s most popular podcast, despite Welles’s songs including many Joe Rogan Experience–core topics: Lyme disease as a government-concocted bioweapon, New Jersey drone sightings, Ozempic skepticism, whistleblower deaths at Boeing. (Rogan himself is a Welles fan.) “He writes a lot of songs,” said Allegra, who was there celebrating her 33rd birthday. “I haven’t listened to every single one.”

In fact, he had released an album of another dozen songs that day, Middle. It is more produced and less newsy than the music that had brought most of the people to the Bowery to see him — subjects tend toward spiritual seeking, insecurity, nature, and the passage of time — and often features a full band. About an hour into the set, Welles brought out a drummer and an electric bassist to run through the new material. Nobody called out “Judas!” “The only filter placed on it was I wasn’t doing topical songs for this project,” he told the Times. “These are ones that are self-indulgent, or at least I feel like they are at times. I like to do both. They’re two different mediums.” With Middle, the medium he’s shooting for might be Spotify rather than the ephemerality of TikTok, the kind of traditional music career he aimed for in his former life as a major-label-signed hard rocker. Will his topical songs still find listeners in a year or three? Or will they feel like novelties, old memes that don’t hit like they did when Luigi was still at large? “The singles he posts are more relevant to stuff that works on social media,” a Long Island preschool teacher named Becky told me. “But with this album, I sat down and actually looked through the lyrics as it was playing, because I wanted to make sure that I heard it.”

Dylan famously chafed at the expectation that he would continue writing “finger-pointing songs,” and Kendrick has objected to the perception of him as an activist. At the Bowery, at least, Welles himself seemed at times a little overwhelmed by the crowd’s relentless earnestness. Mid-show, an audience member was overcome with radical inspiration. “The revolution will not be televised!” she screamed between songs. Welles tried to defuse it with a wry joke: “That’s because there ain’t a whole lot of TV.” She repeated her political prophecy louder a second time. All Welles could do was smile. “Faaar out,” he said, starting once again to play.

Read More Scene Reports

- The Thrill of a Queer Movie That Doesn’t Appeal to Anyone

- What I Saw Camped Out for Paul McCartney’s Secret Shows

- Hollywood Rendered Speechless During Awards Season