On Friday, May 10, John Mulaney’s new live series, Everybody’s in L.A., wrapped up its sixth and (allegedly) final episode. It’s hard to believe that just a week earlier the show was a complete mystery because now it is … still a bit of a mystery, but in a way that made it appointment television.

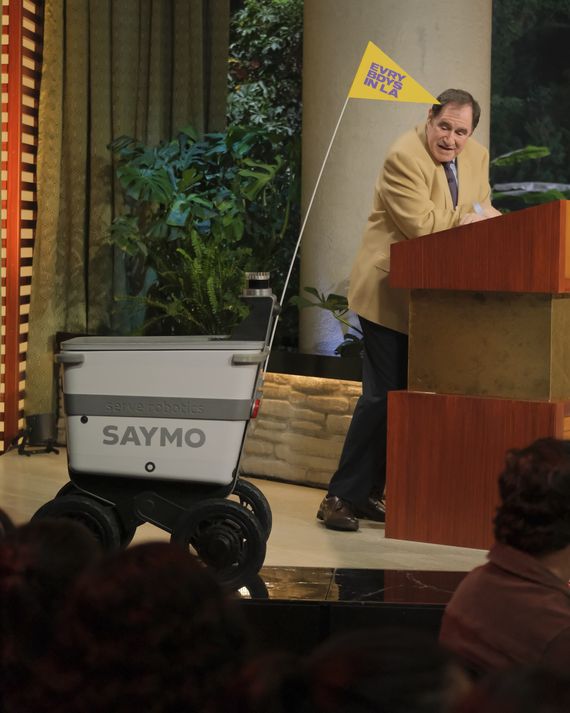

Late-night shows have traditionally been about consistency. For those making them, you’re doing it every night for forever, so you need to preserve energy and ideas. And for those watching, you’re looking for a fun, albeit easy, experience to help in your downshifting toward dreamland. Everybody’s in L.A. was ostensibly a late-night talk show, but one that subverted, if not rejected, the norms of the genre. And it was almost overwhelmed by its own ideas and urgency. The pacing of every episode seemed random with the positioning of the guests, field pieces, comedy bits, and musical acts changing each night. During the show’s premiere, Mulaney explained it would run for only six episodes “so the show never hits its groove.” But in exchange for a groove, Mulaney, his best friend Richard Kind, and his robot, Saymo, made every episode matter.

A lot of the show’s guests tried to capture the vibe of Everybody’s in L.A., but Jon Stewart might’ve come closest during the second episode when he said, “I feel like this entire show is a Banksy.” Is the piece of art the show itself or that the show exists at all? So much of what makes the series distinct is the feeling of these comedians and comedy writers just trying to make each other laugh. Was it funny to have Waingro, a six-scene character from the 1995 Michael Mann movie, Heat, do stand-up? Up for debate, but it sure was to Mulaney and Bill Hader, one of the guests for the fifth episode, who was seemingly there only to laugh.

Given that, “Did Everybody’s in L.A. work?”, “Was it good?”, and “Should there be more of this?” are not such simple questions. They are personal questions. Here are 13 Vulture staffers’ attempts at answering them.

So what did everyone think?

Everybody’s in L.A. ended up being a lot like its namesake city: a sprawling, messy, and frequently chaotic experiment that really should not have worked yet somehow did, often brilliantly. While I have no doubt that Mulaney and his team of writers and producers spent a lot of time thinking about every element of the show (down to those brilliant interstitial title cards), the genius of Everybody’s in L.A. is how underproduced it often felt. Despite Mulaney’s carrying a clipboard around at nearly all times, most of his interactions with guests didn’t feel rehearsed and engineered in advance the way almost all talk-show segments are today. The same went for the audience call-ins and even some of the taped bits, which often had a genuinely spontaneous vibe (like the short about aging punk rockers). Everybody’s in L.A. was least successful when it stuck too closely to the talk-show formula, like with the meh sketch parodying real-estate reality shows. But overall, I never knew what to expect from one minute to the next, and that’s what made me fall hard for this beautiful disaster. —Josef Adalian

The second Richard Kind earnestly disagreed with a coyote expert over a coyote fact, I knew we were cooking with gas. Authentically offbeat moments like that — and the sheer joy they brought to Mulaney — are the crux of what makes this show so wonderful. Granted, its weirdness was best when delivered with a straight face, rather than being undercut by a celebrity guest explaining the joke by announcing how “weird” it was. But those acknowledgements at least highlighted how boring every other talk show on the air is in comparison.

A late-night talk show, as Everybody’s in L.A. proved, can truly be a blank canvas, but they all look exactly the same. While the show’s scripted moments were key parts of subverting the norm, its most impressive feat, particularly for such a limited run, was how it created an infrastructure that fostered organic, unscriptable moments, like Mulaney asking Mayor Karen Bass what car she drove or Luenell asking a seismologist what sparked her passion for earthquakes. Those were genuine questions, which feels like a rarity for this medium. —Tom Smyth

It would have still been a TV miracle if Everybody’s in L.A. were entirely made up of spontaneous, strange moments: Jon Stewart losing his mind over Saymo, reaction shots of Richard Kind with his jaw on the floor at experts sharing facts about palm trees and helicopters, watching the look in Mulaney’s eyes as he made game-time calculations on how to strike the perfect balance between charming and mean as he fielded live callers. It’s corny to say, but there really is an energy to watching something broadcast live, a feeling of going along for the ride.

But then, on top of the live element, the premeditated bits were all strong in their own right: “Oh, Hello” and the Jeremy and Rajat segments were some of the best sketches I’ve seen this year, the courtside nepo-babies bit was pure silly genius, and the filmed interstitials, theme song, and slice-of-life segments looked and sounded great. And having it come out every night for a week made it something of a mini-tradition, quickly becoming comfort viewing that was never boring. I think it’s the most vital piece of Netflix original programming in years. The secret ingredient that tips this all over from goodness to greatness is that Mulaney has never, ever looked hotter. —Rebecca Alter

I consider this show white excellence. It gave us uninterrupted conversations about insanely white fixations (trees; ghosts; O.J.’s whereabouts on June 17, 1994; Ray J); it gave us Weezer as an opener and closer for one episode; it gave us John Carpenter predicting (??) Mexico will take back California; it gave us a proud Mike Birbiglia watching Beck play “Loser”; it gave us Bill Hader giggling through an eye infection; it gave us a Fred Armisen fever dream (a reunion of “Old Punks”); it gave us the city of Los Angeles, according to some of its gentrifiers and Karen Bass; it gave us … Sarah Silverman. Truthfully, it’s oddly nice watching a multi-episode love letter to something you don’t love, like the worst city on the opposite coast. At times, this show had Black excellence too. See George Wallace force-feeding Mulaney very vanilla cake with a giant silver spoon and crossing everyone’s boundaries, minus Richard Kind’s (true love). —Dee Lockett

Multiple times per episode in Everybody’s in L.A., a guest would be in the middle of making a point when, unbeknownst to them, a joke about them would appear via chyron, and they’d look up in visible confusion at the source of the audience’s laughter. That even the comedian guests frequently didn’t understand why the show was funny was the best and worst part of Everybody’s in L.A. Nikki Glaser verbalized this confusion in episode six when she said to Mulaney, “It’s like an inside joke that only you are in on.” Sometimes, as with Jon Stewart or George Wallace, the guests would come in too hot and their desperation to hammer the show into a more recognizable shape with riff after riff made for uncomfortable viewing. But in the moments when everyone on the panel settled in and let the show wash over them, it became transcendent. All of the show’s facets — Richard Kind, the expert guests, the viewer calls, the courtside celebrities, the pre-tapes, Saymo — got more room to breathe, and the show took the crucial leap from Isn’t it funny that this is what the show is? to This is what the show is and it’s funny. Anyway, I drive a Toyota Corolla. —Hershal Pandya

In the first episode, Mulaney stated the mission of the project outright: “To explore L.A., a city that confuses and fascinates me.” It was clear that the intention was to make something that would be confusing in a fascinating way and vice versa, and that’s what the show did.

Everybody’s in L.A. instantly joins the pantheon of great comedic works that come from an outsider’s perspective on Los Angeles and capture the particular strangeness of the city. In that way, almost every creative decision, even the parts I didn’t care for, fed the overall mission. Why would Mulaney have so many famous comedians onstage at once, fighting for attention and/or being visibly unmoored by the fact that they aren’t the ones getting attention? Because that’s what it feels like for Mulaney to live and work in L.A. after nearly two decades in New York. Even the segments that felt less like sketches and more like sponsored content for the Netflix Is a Joke Festival — like when a random collection of comedians went to an open house — felt like comments on the type of concessions this town forces you to make.

It’s very rare for a comedian to be given the budget and freedom to express exactly how they see the world, or at least a very specific part of it, and also for that comedian to have the varied skill set and taste to pull it off. —Jesse David Fox

Mulaney’s face during John Carpenter’s out-of-left-field, flirting-with-racism spiel on Everybody’s in L.A. about “the help” rising up against the wealthy to allow Mexico to take back California is burned into my mind because it reflected both the reveal-yourself potential of live TV and how uncommon that honesty has become in the late-night format, where so many interactions between hosts and guests feel prearranged. But something about Mulaney — maybe his glib-yet-earnest affect or how open he’s been about his addiction — brought out the hidden depths of people, for better and for worse, on Everybody’s in L.A., resulting in an absurdist experience that felt like you fell asleep in front of a TV screen of static and woke up in a fever dream.

Jeremy Levick and Rajat Suresh with a mean, hilarious, brilliant bit mocking Tina Fey and Amy Poehler fans. Character actor Kevin Gage coming out in a hotel robe and reprising his role as Heat villain Waingro for an inside-joke stand-up set. Red Hot Chili Peppers’ (excuse me, Red Hots’) bassist Flea going on a beautifully freewheeling ode to Denny’s as a great communal unifier. None of these things should go together, and not everything over the series’ six nights worked. But Everybody’s in L.A.’s fuck-it-let’s-try-it energy was a breeding ground for TV that, even when it failed, never lacked for surrealist, deranged ambition. —Roxana Hadadi

Liveness on Netflix still feels a little uncanny valley to me. Comedy specials have no real business being live unless they’re truly pushing for a direction and sound design that tries to embrace that looseness. The Tom Brady roast was successful, but an edited version would unquestionably be funnier. Everybody’s in L.A., though, is the first live Netflix programming to actually take advantage of the inherent silliness of doing it live. The essence of this weirdo thing was the live calls, the uneasy or delightful interactions between panel guests, Mulaney’s “I’m in drag as a professional interviewer” interview style, and Bill Hader showing up with an eye infection and giggling so hard he nearly slid off the sofa. Liveness works best when it reveals things that an edit would try to conceal. Everybody’s in L.A. revealed more about the oddness of being a celebrity (and also Los Angeles, John Mulaney, and earthquakes) than I could’ve possibly dreamed. Also, I drive a blue 2015 Honda CR-V. —Kathryn VanArendonk

I really enjoyed Everybody’s In L.A. when it went full Chris Gethard Show. The panel of guests, the phone calls from the audience, the strange little bits — it all smacks of TCGS. (Especially the “Find Flea” game in the finale, which was almost certainly inspired by Gethard’s dumpster episode.) Mostly for better and sometimes for worse, it felt like anything could happen. The “Earthquake” episode did the best job at capturing that sensibility, probably because everyone was trying to show off for late-night legend David Letterman.

But I think Everybody’s in L.A. frequently followed the letter of chaos, but not the spirit. The phone calls were the most frustrating for me. Rather than engaging with the weirdos who called in, Mulaney didn’t quite know what to do with them. It seemed, honestly, pretty mean. To be fair, he’s always been pretty mean — it was just harder to tell when he was wearing a more traditional suit and talking about Law & Order: SVU or whatever. —Emily Palmer Heller

My initial reaction to this show was a violent physical repulsion. I actually had to turn off the first two episodes because the set made me panic, the echoing of the theater made me feel unsafe, and I found the looseness of it uncomfortable and a little disappointing. Given we all knew there would only be six episodes, I simply expected more from some of the pre-taped bits.

But like a big-city career gal stuck in a small town on Christmas, I was suddenly swept off my feet by the raw charm of something I previously disliked. Jeremy and Rajat surprising Tina Fey and Amy Poehler fans got me good, and the rest of the third episode made me fall madly in love with this show and what I call its mournfully nostalgic ’90s adult-drama aesthetic. It feels very much like Conan O’Brien hosting The McLaughlin Group on downers, a vibe I dig immensely.

While plenty of it remained hit-or-miss for me, the lows felt less important as the highs got higher. The “Reverse Borat” sketch might be the best-written piece of comedy I’ve seen all year. —Anne Victoria Clark

One object captured why Everybody’s in L.A., the most refreshingly organic late-night talk show in recent memory, worked. Not Saymo, the result of a crossbreeding incident involving WALL-E and a Yeti cooler, but Mulaney’s clipboard, a prop/receptacle for show info that the comedian gripped during each episode. The clipboard implied that Mulaney had everything under control — “This is me, organized,” he declared on night three, even though the clipboard was already conveying that — despite the delightful chaos that regularly ensued around him.

Mulaney was so in charge that he showed no discomfort transparently pivoting in real time. When an attempt to chat with international viewers quickly devolved into a bad Zoom meeting, Mulaney said “I don’t want to do this anymore” and cut the segment short. When callers rambled a bit too much, he hung up on them with no remorse. Unbridled mayhem can only work this effectively when there’s a calm, responsible presence steering the vehicle. That was Mulaney, a dad and the dad of Everybody’s in L.A., who was smoother in this role than some hosts who have been doing this for a full decade (cough). —Jen Chaney

Ultimately, everything that didn’t work about the show is the reason that it was so good. Any guest who appeared could with a bit of effort reshape the entirety of Everybody’s in L.A. in their own image. Now, did that make for some segments that did not “work for me” in the classic manner? Of course. It was sad to watch Nikki Glaser not get a word in edgewise because she happened to be paired with George Wallace, for example.

But the looney, ever-shifting nature of the show was what kept me watching. Even if it would make for a higher hit rate, I didn’t want any of the episodes to become more predictable, nor did I want Mulaney to necessarily have a stronger hand as host. Rather than be a strong presence, he was more like a ringmaster who set the tone for the circus, then ultimately just let things happen. I loved, for example, when the L.A. mayor dialed in and suddenly we had to watch Mulaney attempt to deal with her unwillingness to say anything at all. I loved when the show became Pete Davidson and Bill Hader just watching Luenell vibe. I didn’t love the filmed segments because they were too wieldy (as opposed to the otherwise unwieldy program). —Jason P. Frank

Watching this show is like being given a precious, hyperspecific gift from someone who knows you a little too well. One of the beauties of living in L.A. is that nearly every day, you inadvertently interact with some of the most interesting people you’ve ever met. Mulaney knows this, and this is what makes Everybody’s in L.A. so successful. The beauty of this city doesn’t come from its movie stars or overpriced smoothies but from its weird rabbit holes (Terryology), localized interests (O.J. Simpson), and hypnotherapists with terrible wigs.

Something about Mulaney also fits so comfortably as a talk-show host, and coupling him with an impeccable guest curation leads to moments like Ray J talking very candidly about his divorce in episode one and performances from L.A. stalwarts like Joyce Manor and Los Lobos. The only thing it could do to improve is ditch the unnecessary comedians and give us more niche celebrity interviews — starting with Angelyne. —Reanna Cruz

What do we want — and not want — next?

I wish I could metaphorically leave my big-city life behind and marry this small-town guy of a show because I want to come home to it every night of the week. A nightly cadence would also take a lot of the pressure off of everything to work — audience members like me have more patience when we’re not thinking, Time is of the essence. —A.V.C.

This would thrive as a weekly live show. It feels like a natural progression for Mulaney’s career, a great home base for his sensibility to run wild, and a dream opportunity for Netflix to successfully nail regular live broadcasts. My only hesitation would be it hindering Richard Kind’s acting availability. –T.S.

At bare minimum, Mulaney should take his clipboard to other cities on a periodic basis. Austin during South by Southwest? Palm Springs during Coachella? Why not? I’ll go to any city (via streaming) to watch him manage this kind of madness again. —J.C.

Since Mulaney probably isn’t about to completely upend his life and career to become a talk-show host, I’m not holding out for a weekly version of what we saw last week (even if I’d never miss an episode). So instead, he should try doing a batch of five episodes twice each year, starting this December with Everybody’s in New York (for the Holidays). One-hour holiday specials are passé; all I want for Christmas is a week of Mulaney, Richard Kind, and Saymo singing carols and swapping presents with their closest celebrity pals. —J.A.

My ideal scenario is that this becomes a seasonal event on whatever seasonal rhythm feels best for Mulaney (or whatever rhythm he can shake out Netflix’s coffers to support). A week of live shows a couple times a year, either returning to Los Angeles or rewritten as different concepts so it could travel to Miami or Brooklyn or wherever. Is that a profitable model for this kind of thing? Probably not. Maybe Netflix can invent some new festivals to support it. —K.V.A.

While I realize this is antithetical to the show’s entire concept and would make zero sense if Mulaney hosted it … Everybody’s in N.Y. when? Desus and Mero, figure out your shit! —D.L.

I disagree with the people who think Mulaney should take this format to different cities. This show is fundamentally L.A., the way that How To With John Wilson is fundamentally New York. It would be nice to see this pop up for weeklong residencies maybe quarterly, if Mulaney is willing, rather than weekly. I’d also like to see them have some Muppets on. Statler and Waldorf would be incredible guests. —R.A.

First, John should learn how to correctly gender nonbinary people. Second, Luenell needs to become a regular guest. Third, this show should get rid of all filmed segments in favor of chaos and return for a week approximately twice a year. I ultimately came down on the side of liking that Everybody’s in L.A. was an event. If it were too regular, it would settle into a rhythm because the guests would understand what was happening. In order to maintain spontaneity, Everybody’s in L.A. must not become a part of anybody’s schedule. It must be a pop-up comedy program that’s exciting while we have it but not able to be counted on. —J.P.F.

I do think this show would nerf Mulaney’s career if it was on every night, especially live on Netflix, but a once-in-a-while deep dive into a specific L.A. neighborhood could be very silly. I want an episode on Boyle Heights! An episode on Huntington Park! Century City! Topanga Canyon! Rick Caruso’s mall empire! The potentials are endless, really. —R.C.

I don’t think Mulaney could or should continue Everybody’s in L.A. I imagine he’d get bored, and I also imagine a bored Mulaney would be extremely unpleasant. But I’d love Netflix to keep doing a late-night show. What I propose: a new host every week who gets to do whatever they want with it. Richard Kind as permanent sidekick is nonnegotiable. —E.P.H.

Since his network sitcom, Mulaney, didn’t work out, Mulaney’s three big projects outside of stand-up have been Oh, Hello on Broadway; The Sack Lunch Bunch; and Everybody’s in L.A. There are plenty of late-night shows and comedians able to host interesting ones, but there are very few comedians who are able to experiment like he has. I’d prefer Mulaney move on to his next experiment rather than revisit this one. —J.D.F.

Will I watch more of this show if it returns? Absolutely. It’s easy to imagine it becoming a fixture of the Netflix Is a Joke festival or to imagine special one-off editions being commissioned to mark big occasions like the Olympics opening ceremonies or New Year’s Eve. But part of me likes the idea of it remaining mummified in time as is — something we can all look back on fondly in five years with and think, Hey, remember that time we all watched live as a snack-delivery robot tracked down Flea at Denny’s? That was fun. —H.P.

Everybody’s in L.A. could continue on and become, like How To With John Wilson, a seasons-long chronicle Los Angeles and its odd subcultures and citizens, or it could hop, skip, and jump around the U.S., finding versions of Saymo wherever it goes. But a thing should be able to end, especially when that thing is so special and odd that it’s most likely a one-off success in eccentricity rather than a formula able to be imitated ad nauseam even after people get the hang of its deal. (These are my thoughts on Shōgun too by the way.) Let these Everybody’s in L.A. episodes be a crystalline memory, the wackiest dinner parties we’ve ever been invited to and will never be invited to again. Let us miss it. There’s value in that. —R.H.