This article was featured in One Great Story, New YorkÔÇÖs reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In the second-floor room of a small local-history museum in Mabou, a very small village on the western coast of CanadaÔÇÖs already quite remote island of Cape Breton, cartoonist Kate Beaton tells me dozens of little stories. Beaton worked in this museum when she was in high school, fielding questions from tourists and helping people sort through genealogies. She spent a lot of hours alone here amid artifacts, much of them her familyÔÇÖs. There is a cane, the oldest thing in the museum, that belonged to a many-greats-grandfather. Upstairs there are generations of school projects, including her own. There are antique farm tools and jugs salvaged from century-old stills, which remind Beaton of the time her grandfather gathered enough moonshine for a party of farmers from 40 miles around only to find it all poured out after his son tasted it and assumed it was poison. I spot BeatonÔÇÖs first book on a shelf downstairs: Hark! A Vagrant, a collection of her strange, charming webcomics. Later this year, it will almost certainly be joined by Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, BeatonÔÇÖs new graphic memoir.

The online comic ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ established Beaton as a defining voice of online humor in the late aughts. Leaping between Nancy Drew, Ida B. Wells, mermaids, Kennedys, St. Francis, Robinson Crusoe, and the American Founding Fathers, its sharp, daffy feminism reframed familiar figures and stories in order to dwell on absurdities, hypocrisies, and endearing, irreducible human quirks. Its look and sense of humor became a defining aesthetic for a newly social, giddily exuberant online moment, as internet speeds increased, load times improved, and LiveJournal, Tumblr, and other blogging platforms turned into identity-defining scrapbooks, proudly curatorial and full of found images.

At its height in the early 2010s, BeatonÔÇÖs homepage for ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ was getting half a million visitors a month. Her work ÔÇö clean, expressive, hand-drawn black-and-white comics ÔÇö was reblogged and reposted endlessly. One of her most popular characters, a round, splay-legged, wordless pony, would eventually spawn a childrenÔÇÖs book, The Princess and the Pony, and the Apple TV+ series Pinecone & Pony. Today, her early preoccupations ÔÇö feminist and postcolonialist retellings, queering and reconsidering the literary canon ÔÇö feel like prophecies, and her style is widely imitated. ÔÇ£You can see her imprint on a lot of work in animation and in comics,ÔÇØ her friend, the cartoonist Lisa Hanawalt, says. When I ask her to clarify, Hanawalt laughs. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt want to name names,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£A lot of people mimic the way she draws faces.ÔÇØ

Ducks is a fuller expression of who Beaton is and has always been. Where ÔÇ£Hark!ÔÇØ was all humor and history and sideways glances at the idea of authoritative truth, Ducks is a monumental synthesis of Beaton herself, incorporating her personal history, her sense of regional and national scope, and her insight into how people get caught inside massive systems. The webcomicÔÇÖs sense of humor is still there, as is BeatonÔÇÖs fascination with reframing the past for a broad audience. Her style is there too: distinctive rounded lines and her knack for choosing one moment ÔÇö one expression or emotion ÔÇö to elegantly condense complicated moods. But Ducks weaves BeatonÔÇÖs own experiences with warm, humane portraits of the many people she met on the oil sands, revealing a more personal, deliberative side of her storytelling. ÔÇ£That book is a masterwork,ÔÇØ cartoonist Lynda Barry tells me. Over a Zoom call, as Barry grows more and more animated in her praise of the book, she eventually throws up her hands, overcome. ÔÇ£ThereÔÇÖs nobody like her.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£I need to tell you this,ÔÇØ says BeatonÔÇÖs 21-year-old self in the opening pages of Ducks. ÔÇ£There is no knowing Cape Breton without knowing how deeply ingrained two diametrically opposed experiences are: a deep love for home, and the knowledge of how frequently we have to leave it to find work somewhere else.ÔÇØ On that same page, thereÔÇÖs a panel with an illustration of Cape Breton schoolchildren singing a song about how painful it is to work in steel plants or coal mines far from home. ÔÇ£I grew up listening to songs about leaving home, going to work, missing home,ÔÇØ Beaton says. ÔÇ£Storytelling is a big part of the culture. Everyone remembers things. Everyone has a long memory.ÔÇØ

BeatonÔÇÖs own memory is a collection of stories that donÔÇÖt make much sense as single anecdotes. ItÔÇÖs harder to remember individual things that happened during, say, the years she lived in New York, she tells me, because she had so little connection to the city or the people there. But in Cape Breton, every recollection is tied to something else. She tells me about the historian Helen Creighton, who collected Nova Scotian folk tales and songs in the 1940s; that story leads to BeatonÔÇÖs fascination with CreightonÔÇÖs choice to leave out songs she found too bawdy, which then leads to a story about a recent translation of a song one of her great-great-great-grandfathers wrote in Gaelic, which itself is linked to an earlier story Beaton told me about how the Gaelic language in Cape Breton was nearly lost in her parentsÔÇÖ generation. ÔÇ£I think that the fact that everyone is connected, it helps us remember,ÔÇØ Beaton says. ÔÇ£The threads are easy to knit together.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs the way much of ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ works: sets of multiple strips, each their own little joke or story or angle on whatever character Beaton is playing with, so that a whole post collects several ideas or perspectives. On a bigger scale, itÔÇÖs also the design of Ducks: not one clean, carefully developing arc but many small memories set next to one another like a mosaic.

In overalls and an Edmonton Oilers shirt, Beaton strides around the farm that she and her husband, novelist Morgan Murray, bought a few years ago. ItÔÇÖs quite a ways up an unpaved road more frequently trafficked by her neighborÔÇÖs cows than by cars or tourists. Her 3-year-old daughter, Mary, pulls on boots to go let out the chickens. (The black chicken is named Heidi, Beaton says, with the subtlest pause for a punch line ÔÇö because she hides.) One-year-old Charlie canÔÇÖt quite walk yet and cruises around their small kid-cluttered farmhouse beaming broadly. At dinner, Beaton takes me to a distillery where we try to talk amid interruptions from a remarkable number of cousins who want to say hello. Many of them no longer live on Cape Breton, but it feels like dozens are home for the summer, Beatons and MacDonalds and Rankins and Campbells. Her given name is Kathryn, professionally she is Kate Beaton, and┬áat home she is Katie. (This becomes confusing when one of the cousins we run into is also named Katie Beaton.)

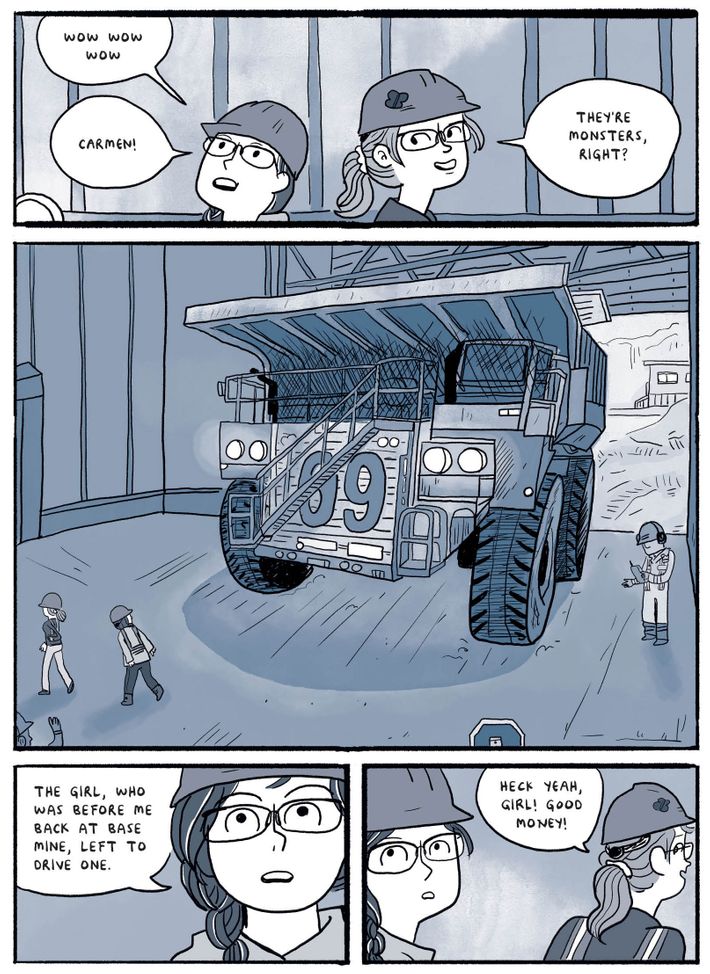

Beaton loves Cape Breton, loves the parade of cousins and the omnipresent web of stories, but when she graduated from college in 2005 with student debt, she couldnÔÇÖt ask her parents for financial help. As in her motherÔÇÖs generation, when everyone left to work in the auto industry in Windsor, or in her grandmotherÔÇÖs, when everyone went to Boston to work as maids, Beaton assumed she would have to leave. Back then, the primary hope for economic opportunity was the Alberta oil sands. Covering 55,000 square miles, the oil-rich area around Fort McMurray became the center of an enormous mining operation in the early aughts, with oil companies erecting remote camps to house the thousands of bodies needed for labor. Although this booming growth is not a well-known story in the United States, it has become a controversial locus of the Canadian economy, culture, and politics, a byword for both prosperity and environmental destruction. BeatonÔÇÖs two years there, first working in a tool crib and later in a supply office at the camps, eventually became the subject of Ducks, but she wasnÔÇÖt ready to make that book when she left in 2008.

Instead, she pursued ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ full time, moving to New York and working out of a shared studio with five other women cartoonists. Although the press called it an ÔÇ£all-female cartoonists collective,ÔÇØ Pizza Island, as it was known from 2010 to 2012, was primarily a group of friends rather than a political act. BeatonÔÇÖs first ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ collection was published as a book in 2011, and her work appeared in MarvelÔÇÖs Strange Tales. She signed a deal for two childrenÔÇÖs books, which eventually became The Princess and the Pony (2015) and King Baby (2016). By 2015, Vulture had published a Beaton interview with a headline dubbing her a ÔÇ£Superstar Cartoonist.ÔÇØ

Then a few things happened in quick succession. In 2014, Beaton posted a long comic to the ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ Tumblr account, a sketchier, five-part serial version of Ducks that began with the incident that gave the memoir its name: a news story about 500 ducks dying in a tailings pond that went viral when Beaton was working there. It sparked intense national interest in the environmental impact of the oil sands. In the first panels of that early version of Ducks, BeatonÔÇÖs cartoon self stares at all the news coverage about the dead birds and listens to a meeting about the changes her employer is instituting to protect wildlife. At the same meeting, thereÔÇÖs an announcement that a man died on the work site a few days before. It doesnÔÇÖt make the news. Few people pay much attention.

Beaton had moved to Toronto by the time that first version of Ducks appeared, still working on ÔÇ£Hark! A VagrantÔÇØ and a childrenÔÇÖs-book contract for Scholastic. In 2015, her eldest sister, Becky, was diagnosed with cervical cancer. The short, dizzy lightness of the webcomic no longer felt like a world Beaton could comfortably inhabit. In 2016, the year after The Princess and the Pony was published, she pitched a book version of Ducks. That same summer, she met her husband, and within a year they had purchased a house in Cape Breton; even before it became clear how ill her sister was, Beaton had been planning to come home. Becky died in May 2018. By July, Beaton began to draw the book version of Ducks. ÔÇ£The first pages were rough looking and needed to be done over again,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I hadnÔÇÖt drawn anything for a long time, and I just needed to start this thing, and I needed something to do with myself other than be consumed with grief.ÔÇØ In May 2019, BeatonÔÇÖs daughter, Mary, was born, one day before the anniversary of BeckyÔÇÖs death.

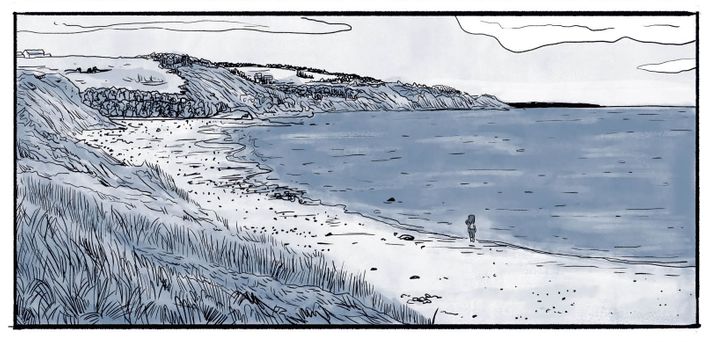

ÔÇ£Therapists donÔÇÖt know how to deal with the camps when youÔÇÖre like, ÔÇÿI was in the oil sands, and I lived in this all-male environment, and it was really fucked up,ÔÇÖÔÇØ she says. We are sitting at a picnic table overlooking Mabou Beach, a landscape I recognize immediately from Ducks. ÔÇ£You explain the culture of the oil sands,ÔÇØ Beaton says, ÔÇ£and theyÔÇÖre just like, ÔÇÿWhat the fuck is that?ÔÇÖ ItÔÇÖs like saying that I went to the moon and it was terrible. ÔÇÿI had a terrible time on the moon.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

Many of the panels in Ducks are cramped interiors ÔÇö tight, repeating boxes that echo the small hunched spaces of bunks, tool cribs, and offices. Occasionally, that claustrophobic compass explodes into sudden scope: Turning the page often reveals a wide-angle landscape shaded and detailed in a way BeatonÔÇÖs figures are often not, drawn with the care of someone who wants to create a record. Not that many people have seen the work sites on the oil sands; even fewer know what itÔÇÖs like to live and work there. Drawn and colored in black and cool grays, though, the oil sands from BeatonÔÇÖs perspective look exactly as she describes them, like a lunar landscape.

Ducks is long, but in BeatonÔÇÖs mind itÔÇÖs longer ÔÇö 900 pages and as true to life as she could possibly get it. ÔÇ£ThereÔÇÖs so much I had to leave out,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I kept bringing back more stories, more stories.ÔÇØ She had to cut people and incidents she wanted to include, not for legal reasons but because there was simply too much. ÔÇ£I wanted to be honest. I wanted to be fair,ÔÇØ she says.

Even in its shorter form, Ducks is a strikingly close translation of the way Beaton tells its stories in person. The book runs chronologically, beginning with her departure from Cape Breton and ending when she leaves the camps. Patterns emerge quietly, coming into focus through a long succession of small scenes rather than an overarching narratorÔÇÖs voice. There are endless safety training sessions in the camps, completely useless and often darkly funny. There are many scenes of shivering in the cold, some of BeatonÔÇÖs most intense memories. There are many, many men ÔÇö most of whom may well be decent, caring people at home, but in the camps, theyÔÇÖre completely detached from the social structures that remind them of who they are. There is perpetual, inescapable harassment. The book depicts two instances when Beaton was attacked, scenes she dreaded including and dreads having to talk about as the book comes out. ÔÇ£I had to put it in the book because if I didnÔÇÖt, it would be a lie. And if I omitted it for my own benefit, which I couldÔÇÖve done for my own privacy, it wouldÔÇÖve been a lie. It wouldÔÇÖve taken out the thing that has affected me the most, for the longest time. So it had to go in there.ÔÇØ They appear in the book in exactly the context she has chosen to frame them: nightmarish, awful incidents but just one part of BeatonÔÇÖs time there. Pulling one anecdote out of the entire work inevitably distorts it.

ÔÇ£She gives such a fair shake to everybody in this book,ÔÇØ Barry says, ÔÇ£including the most awful people. How?! How did she do that?ÔÇØ There are many extraordinary things about Ducks, but this is what lies at the core of it: It is a personal story, and Beaton is painstaking about making sure each character and event is portrayed through her eyes. She doesnÔÇÖt want to make claims about what other people experienced. But she has such immense empathy for those sheÔÇÖs depicting, even the ones it seems she should loathe. It is BeatonÔÇÖs book, but it feels as if sheÔÇÖs constantly handing it over to all these other characters, trying to imagine what it must be like to be them, always balancing her perspective against theirs.

Beaton worries that her empathy will be taken the wrong way, perceived as some kind of structural answer to a story without any real ending: a twist. ÔÇ£Like something I pulled out of a hat. Ta-da! Like what I did on reflection after my time there was discover that I cared,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I lived with these people. TheyÔÇÖre on my Facebook. I see pictures of their family. ItÔÇÖs not a gigantic leap of any kind to care about them, even though you donÔÇÖt like what you read about the circumstances.ÔÇØ

In an email sent after I get back home, Beaton includes a long paragraph on a cod moratorium and the demise of the Cape Breton coal and steel industries, about the way those events fed into the pattern of people from Cape Breton leaving home to find work and the way much of the Canadian economy is shaped by regional inequalities. ÔÇ£Prosperity elsewhere at the cost of families and communities torn apart here, and it has been this way for years. Not that people havenÔÇÖt made good lives for themselves in these places,ÔÇØ she writes. ÔÇ£Opinions on this are not a monolith.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs not an effort to mitigate what she believes or to soften it or draw definitive conclusions. ItÔÇÖs her constant desire to hold on to as many of the stories as she can without letting one overwrite the others.

When people ask her about empathy, I suggest, maybe theyÔÇÖre trying to find a lesson in the book or see it as having a message to take away. ÔÇ£People want answers for why people are shitty,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt have that.ÔÇØ Nor does she have an easy explanation for what Ducks is. ÔÇ£There is no black-and-white for me. But also itÔÇÖs the way I felt my way through the story, my memories of the place, the things I carried around in my mind. Just these imprints of the things that left the biggest marks on me ÔÇö myself and the people I met.ÔÇØ