The 2009 NBC series Kings was meant to be a bold swing — a just-weird-enough-to-work biblical epic that could appeal to both religious audiences and agnostic, liberal viewers. Set in the 21st century, it told the story of the rise of King David in an alternate-universe version of New York City, where battles are fought with tanks and computer screens and palaces are filled with designer suits and cell phones. The main characters — King Silas; his eventual usurper, David; and the various court members and family hangers-on who swarm around them — were engaged in a power struggle for control of the fictional kingdom of Gilboa, their respective levels of divine influence charted in the show’s penchant for decadent symbolism: butterfly crowns, crosses made from shadows and light, ghostly visitations from the Angel of Death. For viewers accustomed to more conventional workplace or family dramas, Kings stood out: Its sets were grander (there were actual tanks), its story lines more peculiar (Brian Cox played a deposed king hidden in a basement), and its humor more idiosyncratic (its royal brats believe “velvet ropes unhook like bra straps”).

Kings arrived at a moment when NBC and the other networks saw their cultural status slipping in favor of attention-grabbing cable programming. In 2008, ABC was still hanging on to the difficult to explain yet popular and critically lauded genre hit Lost, but CBS was floating along on a reliable bedrock of crime procedurals and sitcoms. Meanwhile, shows like The Sopranos, The Wire, True Blood, The Shield, Sons of Anarchy, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad had made HBO, FX, and AMC the new loci of exciting TV drama. A show like Kings was an unquestionably risky investment, requiring a huge production budget (reportedly $12 million for the pilot alone) and a careful marketing strategy that could speak to a precise yet expansive target audience. But it represented the kind of risk worth taking, a show that could give NBC a renewed sheen of prestige and critical acclaim. A show that could fill an ER-size hole in the network’s Thursday-night programming — or else fail miserably trying.

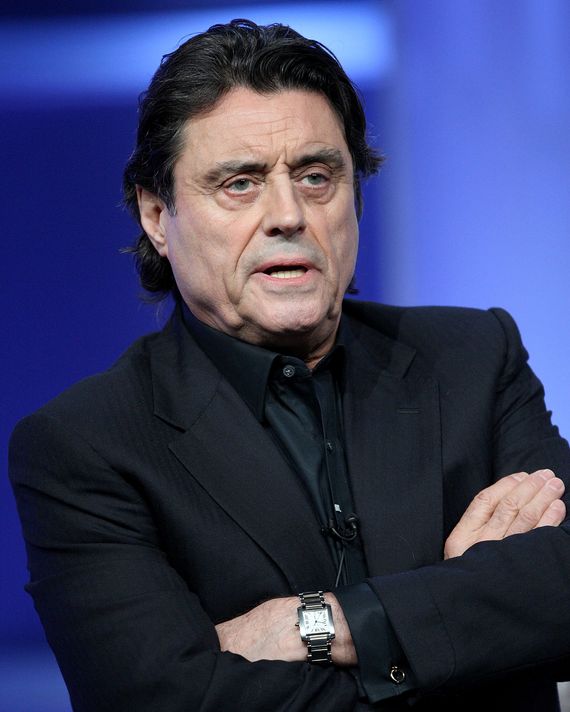

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that between the moment when its pilot was green-lit and the day when that pilot actually premiered, Kings transformed from a future NBC darling to an untouchable hot potato on the programming grid. The first episode aired on a Sunday (it had lost the coveted weekday slot by then) and was seen by a paltry 6 million viewers, sparking rumors that NBC underpromoted the show and intended to cancel it. Still, some critics praised Kings. David “feels like an unexpected breath of fresh air among the more angst-ridden protagonists of the small screen,” Heather Havrilesky wrote for Salon. “As the world looks poised to sink into economic and spiritual quicksand of its own making, this is the hero we’re in the mood for.” The network subsequently aired three tightly written and indulgently rendered episodes, featuring the likes of Ian McShane, Sebastian Stan, Sarita Choudhury, Cox, Eamonn Walker, Dylan and Becky Ann Baker, Leslie Bibb, and more, before demoting the rest of the season (including the arrival of guest star Macaulay Culkin) to Saturday nights. When it was finally canceled, NBC’s president of prime-time entertainment, Angela Bromstad, said, “It doesn’t mean we’re not looking for big ideas, [but] they have to be big ideas the audience can grab on to.”

Indeed, Kings was not the last eccentric drama on network TV — incredibly, NBC would produce Hannibal in 2013. But in retrospect, Kings was a turning point, a moment when the trajectories of network and cable ambitions diverged, when the former became the home of safe, familiar formats, while exciting, groundbreaking dramas were ceded to the latter and, eventually, to streaming. More than a decade later, network dramas have yet to gain the cultural ground Kings was designed to hold, even as the certainty of streaming strategies has begun to fade. The story behind Kings — how it came to be, why NBC decided to bet its fortunes on it, and why that gamble never paid off — yields the kinds of observations you might have watching the show itself: It’s hard to hold on to a throne. But it’s even harder to get that throne back once you’ve lost it.

I. And God Said, ‘Let There Be Bird Crap’

The delight and eventual downfall of Kings begin with the impossibility of defining it. It was a grab bag of narratives and storytelling devices: Shakespearean monologues, loosely adapted Bible stories, a running subplot about gay identity and homophobia, a monstrous mythical representation of death, secret lovers and political machinations. Kings is as much a cohesive story as it is a collection of ideas, with one signature image coming at the end of the pilot: The humble soldier David, having defeated an enemy Goliath model tank, is invited to the palace so that King Silas can publicly applaud him. In a quiet interlude out on the palace’s grassy lawn, as Silas watches from afar, David is suddenly surrounded by a flock of monarch butterflies that lands in a crown formation on his head. The moment becomes a symbol for everything Kings wants to explore: Silas sees the crown as a sign that God may be abandoning him in favor of David. But is it a hallucination? A figment of Silas’s paranoia? Or does God actually exist in this world, and is He signaling his chosen successor?

Michael Green, creator: The show was nothing like anything else on network television. I don’t know what it was. I still don’t know what it was.

Kara Lee Corthron, writer: For all intents and purposes, it’s kind of a nighttime soap if you take away the more fantastical elements. But you can’t necessarily say it’s a family drama. It’s more epic than that.

Julie Martin, writer: It’s like science fiction. But also like a Bible story.

Francis Lawrence, director and executive producer: I liked the parallels to the story of David. But I also liked using that as a template and telling a story that would not feel like a religious story.

Katherine Pope, former president of NBC Universal TV Studios: If we were doing it today, we’d say it’s Succession meets the palace intrigue of Game of Thrones.

Brian Cox (Vesper Abaddon): I thought it was a very bold idea.

Green: It was an alternate history of the world in which the story of King David hadn’t happened yet. Cultural inevitability being inevitable, it just meant he happened in the time of suits and limos, not swords and sandals.

I’d always been interested in the King David story. I was educated in a Conservadox Jewish state school where biblical tales were taught not quite as history but given the same place as anything else. I was on a trip in Israel around 2005. I was having one of those moments where you’re in the place where this tale took place and things felt very real. I went to the Western Wall, and I found myself looking up and seeing all these little birds, these finches and swallows, doing this wonderful dive back and forth around the stones that have been there for a zillion years. It’s funny — I thought, You could see one of those birds crapping in King David’s wine goblet.

Like everyone at that time, I believed that big swords-and-sandals storytelling was only for HBO. I was working on the staff of Heroes. I liked the job, and I thought, I’m not going to leave the staff for anything I don’t love more. But I woke up one morning and had this really clear, manic vision of, Wait a minute — what if we just set the King David story now?

Pope: I remember reading the script in the same way I remember reading the first draft of Heroes or New Girl: I tore through it. And at the end of the pilot, there’s this beautiful butterfly reveal. You’ve been watching what you think is a modern-day palace drama, but suddenly the idea of being chosen by powers bigger than you is dramatized. It pulls you up. I didn’t realize the show was also going to get you in the gut with faith and interconnectedness and beauty and nature.

Green: From day one, I said, “This show is going to be bonkers in its own way. What I’d really like to do is make sure our audience has a toehold.” So let’s do the thing that I’ve seen a lot of shows do well, like Battlestar Galactica or The West Wing, where it’s serialized but every episode is about some core ideas we play out within the episode.

Pope: A lot of the feedback I heard on this show was “It’s too good”; “It’s too smart”; “Why do you have to make these shows? They’re so confusing!”

Green: I remember my girlfriend (now my wife) and I were in Paris together between Christmas and New Year’s of 2006, waiting to hear about the Kings pilot. And, of course, it was passed on by Kevin Reilly.

Kevin Reilly, former president of NBC Entertainment: I have almost no recollection of anything related to Kings and never watched a minute of the show. I do recall reading the script and not liking it and having a pretty spirited debate about it with the staff at the time. They were very enamored with the mythology in the King David lore. I found that world sort of brittle and not particularly engaging.

Green: HBO took an interest, but the response was “This is the kind of thing we want to be making, but we just bought this show called Game of Thrones, and we’re waiting for a script.” My agent sent it over to FX, and they took an interest. I remember having a meeting with them — they said, “How would you rewrite this for our tone?” — and getting really excited. We were thinking of selling to them and then we got the call from Katherine Pope, who said, “Can you hold a beat? I think something might be happening over here.”

Pope: It was a very crazy time at NBC and I think for network TV in general. It was slipping, it was getting overshadowed, and for me, one of my biggest points was we don’t need to cede good shows to anyone else — we’re NBC! My first upfront was after the first season of The West Wing, and the entire auditorium was full of advertisers, the most cynical people. They gave The West Wing a standing ovation; that’s what we could hope for! A show everyone would watch, which would move the culture and be resonant and risky — that’s what Kings represented to me.

Green: Here’s what I know about Ben Silverman. He came to his team and said, “Is there anything you love that was crushed in the last NBC administration?,” and Katherine Pope, who was the show’s champion from day one until she was fired, brought him the script.

Ben Silverman, former co-chairman of NBC Entertainment: I’m a huge fan of the classics, and a history major and a Shakespeare lover, and really appreciated all the allegory and metaphor and language of the piece. And I felt, looking out at the landscape of television, there was just not anything like it.

James Poniewozik, former critic at Time: Ben Silverman was nuts in a lot of ways, and people like to knock him as this philistine who ruined TV or NBC. But the other thing with a figure like that is sometimes they’ll just put anything on the air.

Pope: There was this sense that we were going to make this show that everybody was going to talk about. This is going to be awards; this is going to be culture.

II. All Hail the New York City Tax Credit

Kings was attempting to bring a sword-and-sandals epic into, as Green described it, the world of suits and limos. As a result, it needed to figure out not only how to navigate worlds colliding on the page but how to stage and shoot those pages to feel both mythic and contemporary. Green imagined the aesthetics of the series as something close to a modern-dress production of Shakespeare à la the 2000 Ethan Hawke film version of Hamlet. The show would be shot in New York City, fashioned as the fictional kingdom of Gilboa — akin to a present-day metropolis but ruled by a theocracy — that was at constant war with a neighboring kingdom known as Gath, which deploys Goliath tanks in battles along front lines resembling contemporaneous conflicts in the Middle East. None of this would be cheap to commit to screen. But thanks to some help from the New York State tax credit, the creators set about putting together an ambitious-looking feat of television, helmed by Constantine and I Am Legend director Francis Lawrence.

Lawrence: I was finishing making I Am Legend at the time. I read the Kings pilot, and I thought it was really interesting — I mean, partly because my producing partner, Erwin Stoff, and I had been developing a more period David-and-Goliath story.

Green: What we heard within the day was “We have been trying to do a King David movie for years. We just haven’t been able to crack it, and I think you just did.”

Erwin Stoff, executive producer: What I loved about it, frankly, was its ambition. It was a huge pilot.

Green: When we were starting to budget the show, it became clear this was going to be one of the network’s more expensive pieces, and it made them nervous.

Lawrence: The idea of creating this alt universe that feels somewhat like America but is not America was quite interesting. In battle scenes, it might read a little bit like World War I in terms of trench warfare. I was really trying to wrap my head around Michael’s intentions. Like, was it specifically supposed to feel like World War I, or something different, or a hybrid of something?

Kalina Ivanov, production designer: To me, it was a very European story, in the sense that it was about a war. Because the Americans haven’t had a war on their land since the Civil War, right? But Europe is covered in wars. Every ten years, there’s a war. I came with this idea that there should be contemporary elements to it, but they should be rooted in New York’s old architecture. We should marry the old and the new.

Lawrence: Michael and I both needed to convince everybody to do it in New York. That feels like a real capital. It gives us tons of possibilities. But it was not cheap.

Stoff: The budget for the pilot was around $12 million, if I’m not mistaken, which was enormous.

Margot Lulick, line producer: In the scheme of budgets, it wasn’t horrifyingly low or anything like that. But it was still quite a challenge. Essentially, we were creating another world.

Green: You can’t shoot a show, certainly not an ambitious one, without a tax credit. New York’s filming tax credit had gone away for a while, but then came back right before we were looking to shoot, and suddenly it was like ten or 20 shows were shooting in New York. There was a tax break for the state as well, so we were able to take advantage of both of those credits. We were able to do things like shoot in the city and augment it to create this place called Gilboa and shoot our battle scenes out on Long Island before it was all built up.

A lot of places and people opened their doors to us. BAM let us take over the main entrance. It was Eamonn Walker and Ian McShane having it out on the steps with the cherry blossoms in bloom right behind. The Apthorp building was like a second home. Union Theological Seminary. Hempstead House on Long Island.

Lawrence: We had amazing luck on this job. We found this empty mansion in Sands Point, around the area The Great Gatsby is set, where Charles Lindbergh hung out, right on the Sound. It was empty, but it was also owned by the state, so it had some incredibly, incredibly low rental fee. I want to say, like, $1,000 or something. If it was a personally, privately owned mansion of the same kind, you’d be talking, I don’t know, $30,000 or $50,000 a day or something insane.

We shot the battle scenes out at Far Rockaway. It was some new residential housing project they were going to be putting up. So we had huge, almost endless, out-to-the-horizon swaths of dirt that we could dig our trenches in and bring our tanks out to. It had been raining a bunch, so it made it really muddy, which was a giant pain in the ass to shoot in, but it looked amazing.

Ian McShane (King Silas): I remember filming over in Brooklyn, watching tanks come over the Main Street of Brooklyn! You’re going, Wow, that’s very exciting!

Lulick: Tanks are tricky. First, we had to find them, and we had to make sure they worked. Francis wanted them to work, which is valid. Then they have to be moved at night. They have to travel in the later hours, when there’s no rush hour. They have to go over certain bridges.

Green: We really wanted to use Jazz at Lincoln Center.

Stoff: It was a hugely, hugely expensive location in which to shoot, and it was a very ambitious scene, and the network and studio said categorically no. But Francis and I really felt it was an absolute necessity in terms of conveying the scale of the show. We had it planned to shoot in one day, and they said, “You can never do this in one day.” Francis and I wound up putting the money up ourselves out of our fees. He did 80 setups in the course of that day, and we shot the entire thing in one day. The studio was true to its word, and when we came in at or under budget, they gave us our money back.

Green: We shot it and then we ended up building it to 65 percent scale onstage to be able to use that space and its likeness going forward for the series.

Lawrence: I wanted to make sure the show had some scope. In my experience, a lot of network TV shows, especially at the time, would have done something about an eighth of the scale, and it would have felt kind of network-y, and I was hoping for it to feel more cinematic.

Lulick: All shows are challenging, but this was especially challenging. There was always a touch of spiritual beauty to it.

III. Casting the Court

To fill out that theocratic, not-quite New York, Kings cast actors who were both rising stars and those considered, at the time, to be above network television. The key roles were Silas, the king of Gilboa who has seemingly lost the mandate of God; David, the princely young hero whose defeat of Goliath (that powerful enemy tank) makes Silas uneasy; and Jack, Silas’s son, the heir to the throne who is hiding his sexuality and resents his father. The leads went to McShane, Christopher Egan, and Stan, respectively — the first as firmly established of an actor as a TV series could get, the other two on the precipice of breaking out. But like any good tale of palace intrigue, even the small roles pulled from a bank of New York talent, casting a who’s who of Hollywood past and present, from Culkin as an exiled nephew to Choudhury as the king’s mistress. It was such an appealing project that Kings managed to recruit not one but two Bakers of character-actor fame.

Kim Miscia (casting director): Kings was the most exciting network pilot of the season. Actors were fighting for the roles. David and Jack were two juicy roles that the whole industry was going after, so we really had our pick of the cream of the crop. We saw actors in N.Y., L.A., and across the globe.

Green: Sebastian Stan was the first major role we cast. It was my first time casting a show, so I wanted to be deliberate about it, wanted to see everyone before making a decision. And yet Sebastian Stan came in, read for Jack, and it was like, “We’re done. We don’t need to bring in another one.”

Sebastian Stan (Jack Benjamin): It was the only time I auditioned for a show without a director or producers present before anyone was cast. It was only one audition. Meant to be.

Green: Historically for actors, I never have someone in mind. It’s always an invisible face. For Silas, that was not true; I always imagined him as Ian McShane. There was an expression that was very popular before TV became as prestigious as it is today: “NITV — Not Interested in Television.” It was for people who considered themselves film actors and thought TV was beneath them. Ian McShane was definitely NITV, so we started going down the list of other people, some of whom would have been great. But then one of our executives had just spoken to Ian McShane’s manager, and he said, “Have you guys thought about Ian McShane for this?” And I said, “This was written for him!”

Beth Bowling (casting director): Producers wanted to take a few big swings and felt like King Silas needed to be played by a real heavyweight to anchor the show. I remember we were all a little skeptical that Ian would really consider. He still had a lot of cachet around his performance in Deadwood, and it seemed like an unlikely jump from HBO to network television.

Pope: I remember falling on my sword for the Ian McShane deal. He did not want to do a six-year deal; he wanted to do one year. NBC was so traumatized by the fact that they hadn’t made a series-regular deal for Martin Sheen in The West Wing pilot that they said we can’t not have an actor for the run of the series — “We just don’t do that.” I said, “Michael has a plan! The character is going to die!” And they said, “Yeah, well, Aaron Sorkin had a plan that the whole show was going to be from the point of view of the staff!” It’s hilarious now, because everybody makes one- or two-year deals. I think we ultimately made him a three-year deal.

McShane: I was doing the Pinter play The Homecoming in New York at the time, and I had a meeting with Michael and Francis Lawrence, who’s a terrific director. I was just about to go back to England and do a movie. We managed to fit in the pilot for this.

Green: For the David character, we needed to see someone with a natural inclination to goodness that wasn’t cloying and you could believe and get behind. But we needed someone who could evolve over time into something more sinister. The reason King David is an immortal character is because he starts so auspiciously and becomes everything he had to replace and worse.

Miscia: There were several actors we liked, but something about each didn’t feel quite right for the character. At the last minute, we discovered Chris while combing through taped auditions from Australia. He had this earnestness mixed in with his charisma, and it was like, Eureka! He’s our golden boy.

Christopher Egan (David): It was one of my first big jobs. When Kings came about, I was going up for a film: that Bruce Willis film set in the future — there’s robots. But when Kings came about, I was like, Okay this is interesting. I grew up in a pretty religious household, so I was very familiar with the story. It got down to those two roles, and I did not know what to do and just trusted in God and the universe. Then I got flown to New York, and I read for Michael and Francis Lawrence. I got on the plane back to L.A., and by the time I landed in L.A., it was like, “You need to get back on a plane. You’re going back to New York, and you’re going to start shooting.”

Susanna Thompson (Queen Rose Benjamin): I remember it came in pretty fast. My agent and manager said, “This looks really good. They would like you to run over and be put on tape in Los Angeles.” I think everyone else was in New York already in terms of the producers and Michael. It was the first time, actually, I had auditioned via a form of Skype, I guess.

Green: Being friends with Bryan Fuller, we worked together on Heroes, and I watched what he did with Pushing Daisies. I learned to never compromise ahead of the game, push for the strongest vision, always cast every role with the best actor that you can find, no matter what. Pushing for smaller roles to be cast with Dylan Baker and Becky Ann Baker — we knew if we had the right person they’d become bigger.

Dylan Baker (William Cross): What I remember is how terribly exciting it was and a feeling of majesty.

Becky Ann Baker (David’s mother, Jessie Shepherd): Dylan and I both still have down vests that say “Kings Season 1.” They’re super-comfy. The Kings vests still get used by everyone. On any given set, you’ll run into your Kings-vest people.

Bowling: Erwin Stoff really thought we should think out of the box for the role of General Linus Abner. The creative team did not want to cast the role as your stereotypical general that audiences were used to seeing on network television. Our associate Nadia Lubbe brought up Wes Studi, and everyone felt that we had not seen much representation of an Indigenous actor on network television in a role with power and command.

Green: Marlyne Barrett was essentially a guest star, but she was so strong as Silas’s aide Thomasina that we decided to make her full cast mid-run.

Marlyne Barrett (Thomasina): It was the funniest thing — he said something to the effect of “I’m calling you to offer you a home on our show.” And I remember thinking, This is the sexiest offer out there. Do you remember that movie The American President when Annette Bening gets a phone call from the president? That’s how I felt.

Green: Seeing the actors in something else — like seeing Sebastian Stan in Destroyer and going, Fuck yeah! Told ya he was great! — I feel that pride on the casting level, absolutely. Every one of them.

IV. How Much Faith Do You Need?

Although it was based on a familiar Bible story and explored ideas of faith, Kings maintained a deliberately ambiguous relationship with the divine. Silas speaks to God and believes he hears God answer him; David likewise seems guided by what God is pushing him to pursue. But Kings never makes it clear whether God or some other supernatural power is actually acting in the world or if, in fact, the characters are attributing their ambitions and anxieties to a higher power that exists only in their minds. The series’ idea of morality and judgment is bound up in that ambiguity. Stan’s Jack Benjamin is closeted, eventually developing potential feelings for David, and Kings plays with whether God punishes Silas for demanding that Jack hide his sexuality. It also speaks to the show’s unusual cultural position as both a Bible adaptation and a sympathetic portrayal of a closeted gay man. Kings appeared on network television at a time when American popular culture was hesitant about depicting queer characters and interested in appealing to Christian American audiences (and also wary of angering them).

Lawrence: My first two movies had elements of God in them, and I found it quite polarizing. As soon as you start really mentioning God, it’s very easy for a huge part of the audience to suddenly feel, Oh, wow, they’re preaching this to me. I wanted to make sure it didn’t feel like that. I wanted it to be as universal as possible. These characters believed in some kind of deity, but we weren’t specific in what that deity was, and therefore we weren’t preaching Christianity to the masses, even though these are stories from the Bible.

Green: I had two writers for whom God was a regular part of their vocabulary and figured constantly in their personal or family views. One of them was a practicing Christian, one of them a practicing Muslim, and for myself, who grew up and was educated in the yeshiva circuit, the constant narrative of God’s mentions is commonplace. That played in contrast to the rest of the writers, for whom the mention of God on a daily basis was sort of a fly on the angel food cake. And that was great. We wanted it to work on both levels.

Corthron: I think God works in the show in the same way it works for people in reality: People who are able to see miracles believe they can go outside and have a butterfly crown. That was part of what was so cool — it was this person’s interpretation of God. This is how a king, who is a narcissist, sees his relationship to God. You get to decide for yourself how supernatural it is. Or not.

Martin: Michael and I sat down and were figuring out the iconic biblical tales we wanted to tell. There was the splitting of the baby. No one ever actually split the baby in the Bible, so it was digging deep into what that tactic means to a ruler. We came up with this courtroom sequence for the episode “Judgment Day,” where it wasn’t a child but a pig. He ran wild on set.

Allison Miller (Michelle Benjamin): I vaguely remember a giant pig running through the New York Public Library?

Green: It was part of the original pitch that Jack would be gay and self-closeted and that would be a source of conflict. It met with zero resistance internally. The idea in the pilot that Silas says he might have been accepting if Jack wasn’t in line to take the throne was important to me because I wanted it to be about the family business, not about personal shame or looking down on it. I wanted Jack to struggle. He didn’t think he was a great person and then he’s forced to look in this mirror of David. I was really interested to play out when David became aware of Jack’s feelings for him. I don’t know that it would have been erotic love, but I don’t know that it wouldn’t have been. We just didn’t get to explore it fully.

Stan: I think, in season two, we were gonna explore more of him embracing himself and growing into it. In that first season, it was important for him to go through all that. He needed to get past his father’s approval and accept himself wholeheartedly.

Green: My hope was, by the time we got to those stories, the buy-in on the show and the tenor of the country would allow it to be as sophisticated as if I was producing and writing it now. If I have a regret on the show, it was in killing the character of Jack’s lover. He was this wonderful actor who was in a Broadway touring company, and we couldn’t have him, so we thought we’d rather lose him than just pretend he wasn’t there. But the presumption of suicide in a gay character is something that has rightfully been dinged as a trope. No one ever yelled at me about it, but I feel like I should have spoken to more people and had known what that error might have meant to some people.

Stan: It was always about a good script, great complex characters, and good people to work with. The rest didn’t matter. I still feel that way.

V. The New York Public Library and Whitefish Salad

For a few months while shooting the season, Kings existed in a magical state of possibility and optimism. The pervasive sense was that the show was both special and supported by NBC and that the network was allowing the production to have creative freedom over a project distinctly unlike other network shows. This mentality led to decadent feasts onscreen (literally) and expansive thinking about the future of the show and seasons ahead.

McShane: Silas’s wife was played by the great Susanna Thompson, who was terrific — a Lady Macbeth figure, if you like. They were this power couple, and her brother was, like, a Dick Cheney–type around the deep state, involved in money and power. Dylan Baker was playing the complicated brother-in-law. Silas had a spiritual adviser, played by Eamonn Walker. We had a sequence where Death appears to Silas in the form of a woman haunting him. We improvised this whole sequence in the house where he’s haunted by Death and God knows what — I mean, great stuff.

Barrett: You should have seen the atmosphere. We would shoot in the New York Public Library, and there are times when Ian McShane and Michael Green would go into these discussions about comic books, about the strategies of the First World War, or Napoleon, and they would go on and on. I would come in and go, “What the heck are you guys talking about?” Laughter would break out in the hallways of the New York library.

Joel Marsh Garland (Klotz): As Michael presented it, my and Jason Antoon’s characters as a unit were the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of the piece. They were using them as a frame, so it was a little more like the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead version, these slightly comedic characters who are on the fringes but occasionally give us reference points for the story.

Jason Antoon (Boyden): We were important characters, but we were the comic relief.

Garland: I remember shooting on Halloween night at the library, being up all night while everyone’s walking around in costumes. There were so many fun nights.

Antoon: Every time we ran into Ian McShane on set, he’s the most jolly. He’s like, “I gotta send you this YouTube.” This was when YouTube links were the viral videos. We were sending them to each other. Ridiculous. He was talking about them all the time on set. Leprechaun video — that is the one he sent me.

Green: My assistant came in one day a little ashen and said, “McShane wants to talk to you in his dressing room.” I hadn’t even seen his dressing room. I was like, What? Oh, shit! He’s going to rip me apart! He was in his robe, changing. He says, “We have to talk about the scene,” and I thought, Oh boy, here it comes. It was a scene where he brought a bunch of food into the prison cell of a former adversary, played by Brian Cox, so they could feast together. I’d written that it was all this fancy French food, and he said, “If I’m really going to eat something and enjoy myself, shouldn’t it be delicious Jewish deli with schmaltz herring and corned beef?”

We shot the scene. He cracked open the food, and they went through a quart of schmaltz herring together during the rehearsal. We realized, Oh, he was thinking about lunch! He just wanted some great food with it!

McShane: Coxy was an old friend of mine — Brian. We had that wonderful scene together. Zabar’s whitefish, I seem to remember, played a large part.

Cox: There was a whitefish salad — that’s right. It was so bizarre. But that whole show was really bizarre.

Thompson: With somebody like Ian, you have to come ready to work. Early on, we were rehearsing a scene around the breakfast table, and there was something funny that had happened and he started to laugh. He looked at me, and he said, “Suzie” — only my family has ever called me Suzie — “it’s going to be a long haul, and if we don’t laugh, we’ll never get through this.”

Green: I always knew the second season clearer than the first. It was going to be a little bit like A Tale of Two Cities: Silas’s degradation and David’s ascension. I was desperate to tell the story of Silas slowly going insane. There were so many great plans for that struggle for him: What does it mean to be someone who has lost God’s favor, God’s ear, God’s voice — or, conversely, to believe that you had?

And there was a long, long game plan for it. There was a version of the show where, in later seasons, we would jump quite a bit of time … certainly David as king ascendant and playing out his marital choices, but even further down — I mean, the Book of Samuel and Kings has some really rich stuff. And we’d eventually get to him as an old man deciding who should succeed him and his troubles with his sons.

VI. The Locusts Descend

In July 2008, just as production was wrapping on the pilot, NBC presented Kings at the Television Critics Association summer press tour. The panel included Green, Stoff, Lawrence, and much of the main cast, but the pilot was not yet available for screening, so critics were only able to watch a few clips. Although some seemed intrigued, most struggled to understand the premise of the series, foreshadowing a later challenge. “I know you’ve just started explaining what’s going on,” one TV critic commented at the panel, “but could you maybe do it in a little more comprehensive way so we can figure out what this is about?”

Unnamed TV critic (excerpted from the 2008 TCA transcript of this panel): You say you’re creating an alternate world, so obviously you can’t have it filled with celebrities and pop culture from this world. Are you going to deal with that at all? Are they going to sit down and watch TV? Are they going to have books to read?

Stoff: If I might, a very simple way to think of it is that this show takes place today in a country you haven’t heard of. Any of the things available to us are available in the world the show takes place in.

McShane: I mean, there’s no apocalyptic voice coming on, saying, “It’s the year 2025. The world is in disarray.” We don’t wear overalls or some kind of strange one-pieces.

Unnamed TV critic: So there’s a United States, there’s a China, there’s a Russia. It’s this world — it’s just not a country we know?

Green: Not necessarily, no.

Lawrence: It’s a familiar world.

Unnamed TV critic: Okay, now you’re not making any sense at all.

McShane: Did you just say you’re not making any sense, or we’re not making any sense?

Green: No, he said we’re not.

McShane: We’re not making any sense? Is that what drama’s about? Isn’t drama — excuse me for your ignorant remark. Isn’t drama — we’re not making any sense? What the hell kind of a question. You ask a question — you want an answer or not? The world — drama is built on biblical, the greatest novel written by 50 people ever. If you can’t get a good story from that, you can’t. What do you expect — it all spelled out for you now? That you should know what kind of pop culture we’re going to refer to? Britney Spears’s new child?

Unnamed TV critic: No, no, no. But the answer to the question was that it’s a country I’ve never heard of, but it’s going to be filled with the things that are available to me in this world. So I naturally followed up by making sure I understood, in saying that it is this world? And then no — it’s not necessarily this world.

McShane: It is this world, yes. It’s what he said. He never said —

Lawrence: The difference is — the difference is that you don’t have Starbucks. You have a coffee, but it’s not Starbucks. You don’t have a BlackBerry, but there’s phones and cell phones. There’s no Britney Spears, but people sing songs.

Thompson: But just to answer his question: There’s not necessarily China.

Green: They were asking about a subtle point that we just hadn’t talked about with the actors, which is that this is an alternate history of the world in which the story of King David hadn’t happened yet. In the quickness to answer a normal question from a normal reporter, you get a headline about a stutter and it makes for brief news. I remember people taking that a little harder than they needed to because it felt like it became the story. I think we were all like, No one’s going to remember this for more than an hour and a half.

Pope: It was the craziest thing. The headline that ran later was “Ian McShane of Kings Spars With ‘Ignorant’ TV critic.”

VII. Jeff Zucker Brings the Darkness

Kings was unofficially slated to premiere in the spring of 2009 in NBC’s 10 p.m. Thursday-night slot, a prestigious position previously held by the network’s blockbuster series ER. That time slot was a gesture of confidence in the series, and as production continued on Kings, executives began to plan for how best to promote it. It was an especially important and challenging task given the show’s complexity and its position as a tentpole series for NBC. Critical reaction was mixed, with some critics praising the series’ ambition and others expressing uncertainty about its coherence. The critical response ultimately would not matter much, though, because in late 2008, NBC’s CEO, Jeff Zucker, began to dismantle the network’s executive programming team, first by firing Katherine Pope in December and eventually by removing Ben Silverman in July 2009.

Green: I have to emphasize that we all really liked the creative vision of the show and were supported in all the things we collectively agreed we wanted it to be. All our conflicts or problems came when we were all but done and it was about to launch under new management.

Pope: I was like, We need to tease. The advertising campaign had to build and build so that when the audience came to the show, they knew what to expect. I felt like we had to weave them into this world.

So there’d been this very long-planned, tiered thing. And I remembered they executed step one and then I got fired. No more steps were executed.

Thompson: On the trains going up to Connecticut one weekend before we were through filming, around December 2008, suddenly there were these mysterious posters with butterflies announcing the show — announcing but not announcing. It was just sort of this mysterious campaign popping up all over New York.

Miller: The advertising was confusing because I just kept seeing our show be advertised as the orange monarch flag. I thought, What is this? I don’t know what this is — anyone walking by this has no idea what this is.

Green: It was a butterfly logo and a couple images, six to eight months before the show premiered. It was in movie theaters, and there were posters that went up around the city that said, “By order of the king, clean up your trash.” But they were considered “viral” because you didn’t know what it was an ad for. You knew it was an ad, but you were like, Oh, can’t wait to be told what that is.

Corthron: One of the writers I was working with, his friend came up to him and said, “That show is about Nazis, isn’t it?”

Green: The proper campaign was scuttled at the last minute to save pennies on the dollar, for reasons having to do with Jeff Zucker. We were supposed to have a 30-second Super Bowl spot or share a 30-second spot with another show. We did that thing where we’re all sitting around, waiting to watch the ad, and it just didn’t happen. They just didn’t air it. We were baffled and embarrassed and we called and said, “What happened?” And we were told that Jeff Zucker sold away the spot either the day before or the day of, because why not?

Pope: One of the heartbreaks of me getting fired was that I was so devastated for the show. I felt like I was in a position to protect them, and to clearly deliver what I thought the opportunities were, to communicate to people. I had the relationships to get the difficult shows through. It’s so sad — I felt so bad.

Barrett: I remember thinking to myself — when Katherine Pope left and we were done shooting the last episode — that there was a sense in the air that something was wrong. The market had crashed. The champion was not there.

Antoon: As soon as the new boss comes in, they’re like, “No, it’s not my show. We don’t want that anymore unless it’s a huge hit.”

Ivanov: So the people who cared and wanted to experiment and were bold, you know, went away in the middle of the show! We became an orphan — an orphan that the new regime didn’t know what to do with — and we were too odd. We were just too artsy and too odd.

Silverman: Truly, in my heart, I didn’t think it would work for a wide audience, unlike some of the other bets we made as we went along. It got a little away from itself. You need the logline to be inside the piece, and it just didn’t have that. Kings was a thing on a thing, and it was just one thing too much.

Lawrence: I remember Michael and I went to go meet with Angela Bromstad, who was the new president of Universal at the time. You could see she didn’t really even want to meet with us. She gave us about three and a half minutes. She totally did not get the show. We had to be adopted by this group that did not get it at all.

Angela Bromstad, former president of NBC Entertainment and NBCUniversal Studios: I was living in London overseeing the international television-production arm, and I was summoned back to a job in L.A. that required me to take over the network and the studio. Maybe I saw three episodes of Kings. And then I saw three episodes of Southland, which was developed by Ann Biderman and John Wells. The decision had nothing to do with the people involved. I had a gun to my head, and I had to decide if there were any last-minute schedule changes that I wanted to make, and the obvious one seemed to me to put Southland on Thursday. I had to make what I thought was a commercial decision.

Poniewozik: This was definitely at the point when a collective decision got made: We’re pulling back network TV’s ambitions. We’re going to put on what we can afford and slow the descent on this thing for as long as possible.

Green: They did put out a poster that was the back of David looking at the city, with the flag. It’s a nice image, but the idea was that the real posters would turn him around and you would see his face, and it would say, “One will rise, one will fall.” There was a matching one of Ian McShane. It was a clean concept but more to the point. It was going to tell people that a show existed and that it would be on television. They kept telling us they were going to go up and then they never went up.

The punch line is that the posters were used about a year or two later for another show. They used the basic shape and design and art of the poster for a show called The Cape. I remember driving down La Brea and seeing it. I had to stop the car and laugh. Network television didn’t die; it committed suicide by doing silly things like saying, Oh, we’ve already got a poster! Let’s just use it two years later!

We always said, “There are a thousand ways to market this right. There’s one way to market it badly and say, ‘This is an alternate America. What if America had a king?’ So we all agree we’re never going to do that, right?” And at the last minute, that’s the ad they asked me to approve, and I said, “DO NOT DO THAT.” Showrunning makes you turn into a volcano from time to time, and I went volcano — and they aired it anyway a few weeks before the premiere.

VIII. Wrong Place, Wrong Time

While Sunday night is now the best-established home for tentpole, conversation-driving TV, moving Kings from Thursday to Sunday was a distinct demotion in 2009. The premiere episode on March 15 received viewership numbers that would be impressive today but at the time were considered extremely underwhelming. Absent any network support in marketing or a strong lead-in series, the ratings only dropped from there. Four weeks after the show premiered, it was moved to Saturdays at 8 p.m., probably the only time slot less auspicious than Sundays. Then the show disappeared until the summer, when NBC burned off the last seven episodes in what is usually the network-TV doldrums of June and July. Its cancellation was all but guaranteed.

Stan: When we got moved to Sunday, there was a bit of a Hmmm, okay.

Annamaria Sofillas, former intern: I was there when they got the call. We saw Michael get on the phone and leave. He came back in and said, “They’re changing the slot.” He didn’t look sad; he was still trying to hold it together. But you could tell. I think he said, “They’re moving us to Sunday.” We all knew what that meant. I was a hard-core TV nerd, and when you’re a fan of certain shows, those culty shows, when they move to Saturday or Sunday, you know they’re killing your show.

Bromstad: Kings was serialized. It was a much bigger risk in that time slot. I was looking at it very clinically, and I went with my instinct, which was that Southland was a better fit. Kings, although it was magnificent and it was so well cast, it just did not seem accessible to me. NBC supposedly had a sophisticated audience, but it seemed too esoteric at the time. Southland seemed like a procedural but also like ER. What I didn’t realize was that Ann Biderman also had the intention to serialize Southland.

Barrett: It felt like a specific sabotage. You couldn’t see where it was advertised, and you couldn’t find it. And there was so much money put into it.

Pope: It was so sad. It was like watching a grand Hollywood movie star, like Norma Desmond at the gate: Nobody recognizes her.

Martin: Kings was complicated in a good way, but when I watched it at home, it was such a particular universe, a particular world you really had to immerse yourself in. When you cut to a commercial for McDonald’s, you were completely taken out. It was not a network show. It was like if you were watching Game of Thrones and you cut to a commercial for Pepto-Bismol. These worlds don’t exist together. That’s my theory: It was a cable show shoehorned into a network show. Great show, wrong place, wrong time.

Lawrence: I’m just happy they let us finish shooting the season, and that they aired every episode, and that was that. But it was a really sort of sad, decaying, kind of crumbling ending to what started off as being something so exciting.

Green: When news came that we were officially canceled, I called everyone and spoke to everyone at length. Ian was probably the shortest of them because he just goes “Ah, those fuckers” and is done with it.

McShane: Absolutely. Because what else are you gonna say? You sort of half-know and you say “Yeah,” because the easiest thing is to cancel the difficult show rather than carry on with it.

Cox: It was a bit of a blow, actually. I was desperate to do the show. I think nowadays, you know, Netflix or one of those would have picked it up. It would have been protected, and it would have got dealt with properly. But that was the bad old days of NBC.

Lawrence: Weirdly, my first movie and Kings are probably the things I hear about the most. If I’m junketing around the world, I’ll do an interview, and someone’s off-camera or somebody in a crowd or whatever will be like, “Oh my God, Kings — it’s so great.” It’s like, “Wow. Okay, cool. Thanks.”

Dylan Baker: Wherever we go in the country, if it’s down in North Carolina or Texas, people at the stores, people that work at the food markets, at the hardware stores, they’re the ones that say, “Kings — I loved that show.” And it’s fascinating. I’m amazed that we’re not still running, actually, because that kept up for a long time.

Green: Look, the network was doing what a network does, and we chose to put it on a network. So you can’t blame a network for turning over and changing its interests. I’ve become less cynical about network television these days, actually. It was in that weird transitioning period where they were doing radically stupid things to incredible losses.

Bromstad: You know what? Here’s the thing: I don’t know how anything worked on network. I really don’t. And by the way, at that time, it wasn’t working. Nothing was working. The ratings for every show were so, so much lower than when I started.

Pope: What’s so crazy about the supercharged content landscape we’re in now is that I don’t think it would seem like a radical show at all. So many of the questions I got that were like, “What is it, though?” “What do they mean by that?” — so many of those wouldn’t even be a second thought now. It was a really, really different content landscape at that point. People are always saying, “Oh, do something different!” But the system was really built up to tell you what things would succeed and what things would not succeed. We tried that once, and it didn’t work. Doing anything different was scrutinized. That attitude was pervasive through all of TV.

McShane: I know what Michael was trying to do: Michael was trying to make a bit of art, you know. In the face of network TV, you’re trying to create a little art every week. Nothing wrong in that.