Kit Connor made what was possibly the biggest decision of his life while lying in bed scrolling through Twitter. It was October 31, and the British actor, then 18, was in the middle of shooting the second season of Heartstopper, the young-adult Netflix romance series in which he plays Nick Nelson, a bisexual-but-hasn’t-realized-it-yet jock who becomes the primary love interest of the central character, the gay misfit Charlie (played by Joe Locke). The show is a rose-tinted, and often more than a little didactic, depiction of British high-school life, based on the webcomic that became a series of graphic novels by Alice Oseman, which had sold 1 million copies before the release of the TV adaptation. The story takes place in a universe a few ticks closer to utopia than ours, where people still experience the hardships of teenagedom but have the emotional intelligence and the language to overcome them. Characters talk directly, for instance, about the danger of trying to put a label on someone like Nick’s sexuality without really knowing them or to pry them out of the closet. It’s all filmed with a layering of soft filters and edited with fanciful doodling over the screen.

You can find plenty of supercuts, GIFs, and other fan-made creations online celebrating Nick and Charlie’s romance, often bleeding into fandom for Locke and Connor as actual people. But that kind of enthusiasm can quickly curdle as it starts crossing boundaries. When the series debuted in April 2022, Connor tells me, he accumulated millions of followers on Twitter and Instagram within a month and would find himself scrolling through comments online — generally positive, though some came with a streak of protectiveness from lovers of the original work. “There’s something so exciting about hearing what people think,” Connor says, “and then you see one negative comment and think, Oh my God, the world’s ending.”

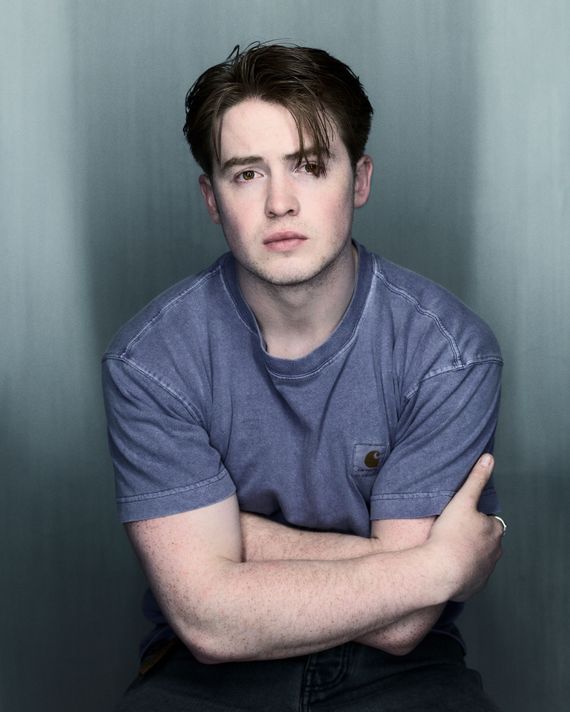

Connor, currently 19 with a swoop of reddish-brown hair that makes him look like a Burberry creative director’s idea of a college freshman, gets visibly tense as he describes trying to process the attention of so many people at once. It’s early June of this year, and we’ve been walking along the High Line in Chelsea, but we’ve stopped at a bench facing the Hudson, where he furrows his brow and squints out toward New Jersey. “I think human beings weren’t meant to meet more than a certain amount of people in their life, know a certain amount of people, or be known by a certain amount of people,” he says. “I always thought I would find it easier — when you’re a kid, you’re thinking, Wow, I’m going to be famous.”

Connor doesn’t linger on the level of scrutiny he started to receive, but it was intense: A portion of fans fixated on the question of whether he, like his character, was queer, their tone ranging from demanding to know if he was indeed bi to accusing him of being “str8 and benefiting off a queer project” or being clearly “straight af” but dodging questions with the “perfect amount of woke brand of political correctness.” Initially, Connor brushed off the speculation, tweeting a few weeks after Heartstopper was released that Twitter “is so funny man. apparently some people on here know my sexuality better than I do,” then saying on a podcast that he preferred not to label himself. In September, he was photographed on location for Heartstopper holding hands with a future film co-star, the actress Maia Reficco, which made certain fans all the more intent on forcing him to disclose his sexuality. He deleted his Twitter account soon after, writing, “this is a silly silly app,” but the messages got to the point of harassment and stalking — “People would start reaching out to my friends and people I was close to about it,” as Connor puts it — which set him off. He certainly would have had cause to be furious, but he couches his feelings to me a little differently. “I think I felt disappointed,” he tells me, “because I was really trying, you know. I really was trying to set that boundary. It was my private life, and I can understand why people would want to know, but I was also, you know, an 18-year-old kid.”

So in bed, after that long day shooting last fall, Connor decided to log back on to Twitter and fire off a message: “back for a minute. i’m bi. congrats for forcing an 18-year-old to out himself. i think some of you missed the point of the show. bye.” It was an entirely impulsive decision. He tweeted it, deleted Twitter off his phone, and went to sleep. “Then, the next morning, I just realized, Oh God, what did I do?” he says. “In my head, I was just like, I want it to stop. I didn’t think about the reaction.”

The response to his coming out was overwhelmingly positive. His cast members supported him (“You owe nothing to anyone,” tweeted Locke), as did Oseman, who wrote, “I truly don’t understand how people can watch Heartstopper and then gleefully spend their time speculating about sexualities and judging based on stereotypes. I hope all those people are embarrassed as FUCK.” Famous members of the entertainment industry publicly and privately showed love. Luke Evans, who is out himself, tweeted, “Seems like things don’t change.” (“I wouldn’t want to name-drop,” Connor tells me, Britishly, when I ask who messaged him directly.) He was the subject of op-eds on when digging into stars’ personal lives goes awry. “I didn’t think it would have the reaction it did,” Connor says, downplaying the moment and his part in it, for not the first time, during our walk. “Gave me a lot of hope for mankind, I suppose.”

But it was also, of course, all quite jarring. At the time, Connor was out to close friends and members of his inner circle but not everyone, so some people he personally knew found out from the tweet, “which made coming out more interesting,” he says without elaboration. He’s not anxious about being limited by the label of being a “queer actor.” “It shouldn’t matter, and in my experience so far, it hasn’t,” he says. “But I want to play roles that are interesting and challenging, whether they’re queer roles or straight roles.”

Connor grew up in Croydon in South London — “Londoners will tell you it’s the dumps,” he tells me, though he defends it — the shy youngest of three siblings. His parents, who worked in advertising, sent him to a Saturday drama program to help him break out of his shell. From there, he heard about the opportunity to do a commercial, auditioned for it, and booked the part. More commercials followed, including one for the ubiquitous British supermarket chain Sainsbury’s, then a few appearances in kids’ roles on British TV. When he was 8, he had his biggest break, playing Rafe Spall’s son in a Christmas movie called Get Santa, which featured Jim Broadbent as Santa. That brought him an agent and, for the first time, the notion that acting was something more than a hobby. “I thought, This is something I could do for a living,” he recalls. “I was also thinking that I was missing so much school. I never thought I could come back and go to university.”

Connor’s love of acting was initially bound up with dreams of Hollywood grandeur, which he still harbors. He grew up watching old films and has a soft spot for movies about movies, like Damien Chazelle’s Babylon — he’ll wax poetic about the scene in which Jean Smart tells Brad Pitt he’ll live forever on celluloid. After Get Santa, he had small roles in the films Ready Player One and The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, among others, leading to a job in the 2019 Elton John biopic, Rocketman, in which he played a younger version of the rock star (Taron Egerton played the adult role). It meant he had to sing and dance, though he currently insists he’s not much of a singer or a dancer. Around the same time, he filmed the more adult drama Little Joe, playing the son of Emily Beecham, who won an acting award at Cannes. Making those movies, Connor felt like he was going from child acting — which is to say mostly reacting to the people around you as they perform — to making acting choices himself.

Connor planned to take a year off after those gigs to refocus on schooling, studying for the British high-school exams known as GCSEs and then hopefully returning full time to the career he’d set his mind to. That plan reversed itself twice: first when COVID scuttled a stab at a more normal high-school experience and second in 2021, when he booked Heartstopper. Connor originally went in to play Charlie, thinking that he probably wasn’t going to land the role of the internally conflicted, recently outed main character but wanting to find a way into the project somehow. “I read him as mentally sort of traumatized,” Connor tells me of an audition. “I probably pushed it too far.”

Nick is a more obvious fit for Connor’s built-in-an-approachable-way looks and sweet demeanor but an acting challenge of its own. In the first season, Nick is seen for the majority of his screen time from Charlie’s perspective as a near-beatific idol, just out of reach. “I saw this light in him; I felt he’s too pure for the world he’s living in. The only world he’s perfect in is the Heartstopper world, I suppose,” Connor tells me. Connor had to live up to that fantasy while communicating that there is a real and more complicated person under the rugby kit. His performance often rests on small fidgets of discomfort beneath a placid exterior. You can sense that Nick is aware both of being watched and, like Connor himself, of the pressure of living up to the idealized expectations of the other characters.

Connor is relieved to say that the way Nick is portrayed in the second season brings the character a little closer to earth. Now in a relationship with Charlie, Nick tries to figure out how to come out on his own terms while acknowledging Charlie’s desire to be out in the open with his boyfriend. We see more of Nick’s relationship with his family outside Charlie’s perspective. He’s got a supportive mother (the great Olivia Colman, also seen in the first season; “Doing a scene with her is going to teach you more than a year of drama school,” Connor gushes) and a tense dynamic with a homophobic brother. On a bubble-gum-colored trip to Paris in the early episodes, Nick is preoccupied by thoughts of his as-yet-unseen French father, revealing that Nick speaks excellent French. Connor says he learned the language for the part while also assuring me his skills aren’t quite up to par. Still, his dedication doesn’t surprise his co-stars. “He has the discipline of an actor who has worked for 40 years and the skill set of one too,” Locke tells me. “He has the ability to be laughing at a crude joke one second and break your heart with his acting a second later as ‘action’ is called.”

Between seasons, Connor spent quite a lot of time at the gym bulking up. In his Twitter days, he’d seen a lot of comments saying he wasn’t as tall and buff as the drawings of Nick. “I wouldn’t say I was forced into it by fans, but it was me as a young adult coming to terms with the body that I had and feeling I wasn’t completely equipped to play the role,” he says. “That wasn’t a good way of thinking, but I was a teenager. I still am.” He now feels he has a much healthier relationship to his body and finds working out to be good for his mental health. Along the way, he has posted a photo or two of himself on Instagram showcasing his progress, which, like his coming-out tweet, have generated internet buzz, though of a much thirstier variety. On his press tour for this second season, he’s adopted an impish approach to dressing for events, wearing a Chippendales shirt at a Washington, D.C., Pride parade and posing in front of a drawing of a penis at a fashion show. Of one shirtless shot, he says, “I saw that picture and I posted it and then I immediately was like, Oh my God, this is embarrassing.” One of his Heartstopper co-stars poked fun at him: “Oh, are we posting thirst traps now?” Connor insists he doesn’t want to be “that guy” but also that he’s a teenager figuring it all out. “Anyone else does it, I’m like, Yeah, absolutely, body positivity!” he says. “But when it comes to me, I’m just like, Absolutely not.”

That resistance to being so image-forward might be attributable to Connor’s desire to outgrow his heartthrob-of-the-moment position. He loves working on Heartstopper — which has already been renewed through a third season — but is opposed to the possibility of ending up like some actors on American teen soaps who have pretended to be in high school for nearly a decade and looks to stars who went from beloved franchises to edgier work, like Robert Pattinson, as career models: “I hate the idea of being a teenager, having your show blow up, and never developing from there, potentially acting like a 17-year-old when you’re 25.”

Stepping outside Heartstopper land, Connor recently filmed the rom-com A Cuban Girl’s Guide to Tea and Tomorrow (another YA adaptation), which led to all those straight accusations, then got cast with four days’ notice as the lead of a “psychological sort of thriller-mystery” movie called One of Us. He has been watching a number of mid-century Hollywood classic films with the likes of James Dean, Montgomery Clift, and Marlon Brando — a group, he points out, that’s full of men who were, by most accounts, queer. Connor talks about building a career with a seriousness of intention that’s both practical and, in its way, surprisingly optimistic, especially for someone who has already endured so much relentless scrutiny. He’s been reading Ethan Hawke’s novel A Bright Ray of Darkness, in which a hotshot young actor much like a young version of Hawke tries to right his spiraling career by doing Shakespeare onstage, a premise that appeals to Connor. While in New York, he has plans to catch a bunch of theater with Locke, eagerly soliciting my suggestions and noting that they have plans to see Jodie Comer, who got started in British teen TV, starring in her Tony-winning role in Prima Facie.

It’s another point in our conversation in which he finds himself at the juncture between childhood and adulthood, shifting between reacting and acting, being perceived and determining his own course. “I haven’t done a play, like, as an adult,” he says. “I’m keen to, hopefully soon. And once I’ve done that, I’d be ready to take it to Broadway” — here the self-deprecation kicks in again — “or maybe Off Broadway … somewhere!”

This shoot and interview was completed pre union strikes.

More on ‘Heartstopper’

- The Weepiest TV Moments of 2024

- Heartstopper Is Coming Out Again Soon

- On Heartstopper, Everything Goes Down in the DMs