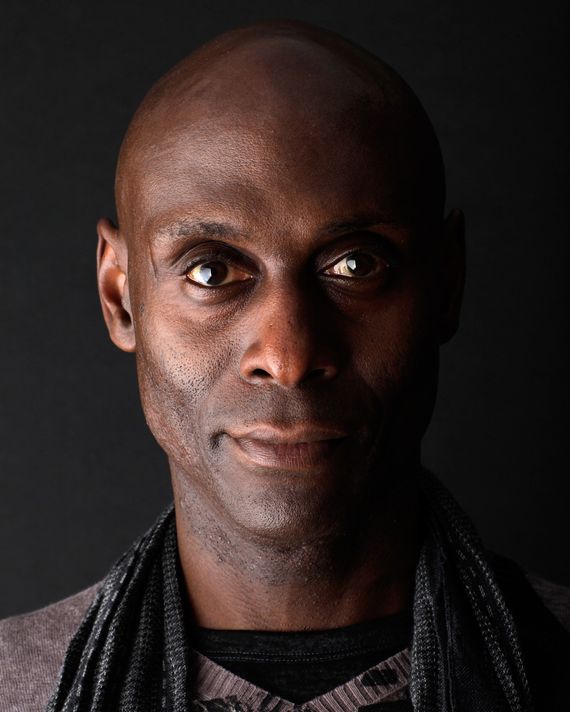

Lance Reddick was an actor of such precision, both physical and emotional, that every little adjustment made in character was a purposeful piece of a coherent whole. Over decades of work in TV, film, and voice acting, Reddick cultivated a certain persona: the perfectly postured, sonorously voiced authority figure; a man of dignity, morality, and some rigidity; the guy to whom others turned when difficult decisions needed to be made. As Thomas Wayne, one of the superhero genre’s most beloved dads, in Batman Unburied; as Los Angeles city councilman Irvin Irving, aggressive and uncompromising, on Bosch; as double versions of the rule-following, then rule-bending, Homeland Security agent Phillip Broyles on Fringe. But Reddick was as magnetic when upholding that image of frosty vehemence and hard-staring loyalty as when carving fissures within it, or when flat-out disrupting audience expectations by distorting his gravitas into something goofier, more light-footed than straight-backed.

An actor who moved fluidly between comedy and drama, Reddick felt like a gift wherever he appeared, from video games like the Destiny franchise (which he also played, posting clips of himself on social media) to celebrity-rattling sketch-comedy experiments like The Eric Andre Show. (Reddick was gamely unflappable in the face of Andre’s weirdness.) He could play it straight for unanticipated humor, using a somber deadpan to deliver a line as silly as “They figured out that the source of the goo is you,” in a Tim & Eric’s Bedtime Stories sketch about a septic tank full of semen. He could go big, declaring with a smile, “Now, we all know there’s no God,” to a room of cowed employees in the Comedy Central series Corporate. He could humanize any character with little notes of mortal concerns: pushing up his glasses before entering a shoot-out as the buttoned-up Continental concierge Charon in the John Wick films; squinting in confusion at a waitress limiting the number of “unlimited” breadsticks his clone can order in the Resident Evil reboot. He radiated masculine grace and self-assured integrity, a sense that his agility and allegiance were always an asset to whomever was lucky enough to count him on their side.

Yet among all of this work — and there were decades of work, more than 100 credits on his filmography, plus an array of still-unreleased projects — the role that gave Reddick the most freedom to wield his many performative gifts was Cedric Daniels, Baltimore police lieutenant turned police commissioner turned defense attorney, in HBO’s The Wire. Reddick had other, longer-running television projects, like the aforementioned Bosch and Fringe, but Daniels was his most defining role. The character is a narrative nexus, connecting The Wire’s police, politicians, lawyers, and bureaucrats not through his mistakes, but through his reliability, expertly conveyed by Reddick’s steady presence and clear gaze amid all that pressure. Reddick grew up in Baltimore, and he returned to the city for David Simon’s series, appearing in premiere “The Target,” in finale “-30-,” and in every single episode in between. That’s 60 total installments in which he evolved Daniels from a chain-of-command-following hard-ass to one of the series’ most consistently principled figures.

The Wire argued many things (that the world is never black-and-white, but all gray; that systems decay from the inside out; that the economic hardships disintegrating the American working class are irreversible), and its characters were all compromised in some way. Daniels wasn’t unblemished; as early as the first season, The Wire alludes to an incident in his past in the Eastern District that made him the target of an FBI investigation. But what Reddick communicated through those minute modifications in gaze, timber, cadence, and body language was the interiority of a man who long ago decided to be better than he once was, and who would try, as much as he could, to model that behavior both for himself and the officers in his charge. And when another character tried to tell Daniels that all that effort was for naught? That meant we got to see him lose his temper, and Reddick was great at that.

Consider one of his most memed lines: “This is bullshit,” first uttered in season-one episode “The Wire.” Daniels has been assigned to lead a special-detail investigation into Baltimore city drug dealer Avon Barksdale. Midway through the season, Daniels is pulled into a meeting with his higher-ups, who want him to quickly wrap up the ever-sprawling investigation and get a conviction on a few isolated crimes so they can “go home like good old-fashioned cops and pound some Budweiser.” Reddick’s reaction here is a master class in incrementalism, a glimpse into his acute understanding of how far Daniels could be pushed in the name of hierarchy before losing his cool. First he looks away from his superior, and quirks his mouth in bemused irritation. Then, that sculpted jaw turns back to his subject, his eyes side-long and scornful. The pause he takes after “this” is emphatic; the rush between “is” and “bullshit” an acceleration of disgust. There are many vulgar moments that became iconic in The Wire, but “This is bullshit” was a glimpse into what Daniels stood for, an ideological constitution that Reddick conveyed with sharp-edged righteousness.

The camera stays on Reddick for that line, because The Wire knew that if Daniels had a punchy line or monologue, the camera should always stay on Reddick to capture the choices he would make in service of a moment. The series turned early and often to Daniels as a contrast to its more impetuous, foolhardy characters, and these scenes, which usually were just Reddick and another actor in conversation, allowed his grasp of Daniels to shine. In second episode “The Detail,” Reddick controls Daniels’s range of reactions — indignant fury to cool abhorrence — as he questions his officers about their attack on the residents of a housing project. The twitch in his jaw as he coaches one of them into a lie of self-preservation gives away his revulsion at using the system to protect a man who blinded a teen. As with “This is bullshit,” Reddick was adroit at knowing when to take a beat or when to sprint, when to make eye contact or when to look away, to exude his seething frustration with the status quo.

When Reddick stood up and buttoned his jacket, a smooth movement that amplified his graceful height, you knew Daniels was fed up with being taken for a fool. When he pulled out the slow blink and head shake, you knew Daniels was going to say something the other person didn’t want to hear but needed to. Reddick was particularly skilled at delivering insults with barbed venom, and more than once his exasperations felt like a mouthpiece for the series’ writers on the societal ills they were addressing: “You’d rather live in shit than let the world see you work a shovel” to the city’s police commissioner; “If a fucking serial killer can’t bring back more than a couple of detectives, what the hell does it matter that you have a fresh phone number?” to a homicide detective requesting more resources. Those lines hit as hard as they do not only because Reddick was never melodramatic or overwrought, but also because he allowed a sense of sly humor, and a winking charm, to peek out from behind Daniels’s surface austerity.

Sometimes, Daniels’s sardonicism came from the same moral code that guided his policing, and Reddick’s physical touches provided enjoyable friction between his character and the criminals he was chasing. In “One Arrest,” he lets a small-time crook and trafficker explain how he would rob a house before introducing himself, with a broad grin and extended hand, as “Cedric Daniels, but I mostly go by ‘Lieutenant.’” In a meeting with Davis, his wide eyes and guileless “Good” in response to the state senator’s insistence that he’s not involved with drugs are wonderfully, mockingly facetious. Even without dialogue, Reddick’s reaction shots were visual gold: his serpentine expression when a racist colleague tells Daniels to put aside “the black-white thing”; his assessing look of amusement at watching the men in his unit struggle to get a desk through a doorway; and his grimly droll response to the traitorous Jimmy McNulty getting into the elevator with him in the series finale. The tightness of Reddick’s face, and his clipped delivery of “To be continued” to the shamed McNulty, assure us he’ll keep his promise of retribution.

In the years since The Wire aired, police-related scandals in Baltimore (including the one that inspired Simon’s and George Pelecanos’s latest collaboration, We Own This City) have raised questions about the impact of “good police” like the one Reddick inhabited for five seasons. But what that argument overlooks is that Daniels was a figure driven not by a romanticized belief that cops are always right, but a hard-earned knowledge that they aren’t, and Reddick walked that line with poise and empathy. The Wire gave Reddick the time to figure out everything that made Daniels tick and the space to share his humanity, the weariness in his voice when he worried that if you “bend too far, you’re already broken,” the gentle guidance to an advice-seeking subordinate that if “you show them it’s about the work, it’ll be about the work.” A character actor whose screen presence was inimitable and who gave The Wire the core of decency it needed, Reddick showed us who he was through his work, too.