ThereÔÇÖs a moment in Last Call, the four-part HBO docuseries based on the book of the same name by Elon Green, where a police officer being interviewed in a talking-head format starts to question the framing of the documentary. ItÔÇÖs a now-familiar device designed as a display of authenticity, sneaking behind a participantÔÇÖs on-camera persona to unearth another kernel of truth. Last Call calls on many of the standard elements and tropes documentaries employee to unleash stories about crime and investigation: drone shots establishing relationships between various locations, a visual timeline sliding forward, re-creations of scenes around where the crime took place playing out through subtle shifts of light and color.

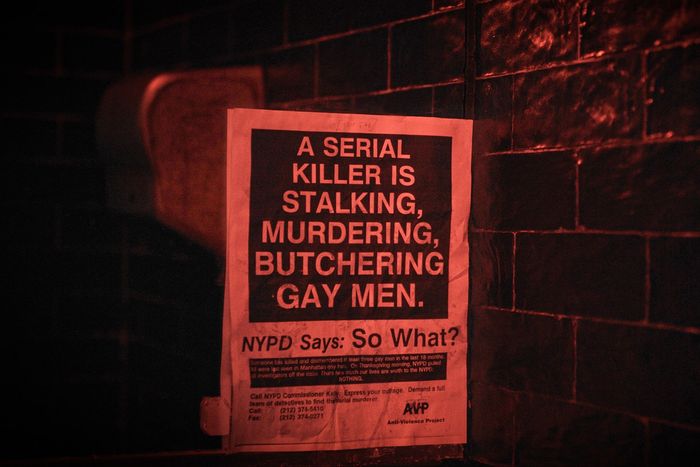

And yet, as Green and director Anthony Caronna explain, Last Call uses those devices for entirely different ends. True crime is the ÔÇ£Trojan horse,ÔÇØ Caronna says, the frame that lets him tell a story about anti-gay violence in early ÔÇÖ90s New York and about the much broader connections between anti-queer political rhetoric and the surge of attacks that follow.

While pursuing that bigger cultural history, though, Last Call still has to tell a gripping story. CaronnaÔÇÖs interest in doing both sides of that work, Green says, is what gave him confidence in the adaptation. ÔÇ£All I really wanted was that it maintain not just a victim-centric approach, but be fully immersed in the period, the politics, the activism,ÔÇØ Green says. For Caronna, it was a process of negotiating between his own early vision and the reality of discovering a story while trying to construct it. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs shifting and changing under your feet the whole time.ÔÇØ

What were you looking for when the process of adapting Last Call began? I imagine it must be nerve-racking to watch someone else start telling the story of your work.

Green: ItÔÇÖs true in the abstract. Ultimately, you get to decide whether or not you want to do this, and that was nerve-racking. But once I found out who would be involved ÔÇö I knew what Liz Garbus had done ÔÇö and Howard Gertler, who became the executive producer, and Anthony, I was pretty much at ease. I understood what HBO had agreed to, their slant on the project, and why they wanted it. I have to say, I was pretty far from nervous. I didnÔÇÖt have any reason to think it was in the wrong hands or it wouldnÔÇÖt carry on the spirit of the book.

What were your initial thoughts on the project, Anthony, as you were deciding how to tackle it?

Caronna: I read the book before it was published, and I was in love with it. I had gone to Townhouse many times before. But I passed on the project ÔÇö I didnÔÇÖt want to do true crime, and I was worried about revictimizing the queer community. Almost a year later, Howard asked me to go to dinner and said he was thinking about working on this project. There was an opportunity to focus on the queer-violence activism at that time. I was drawn to the idea of using true crime as a Trojan horse to have a deeper conversation about the queer movement and what itÔÇÖs like to be queer and face violence constantly. It took us three months to get the pitch deck to the point where we were happy and Elon was happy. Howard and I would go back and forth on it and send it to Elon, and Elon would give thoughts. We brought it to HBO, and they immediately green-lit it.

What was the process of finessing that pitch deck? It sounds like a lot of the conceptual work happened in that development period.

Caronna: Elon was very generous to give us all of his audio recordings, all of his research for the book, so a lot of the investigation work was already there.

Green: The pitch deck was the first time IÔÇÖd seen a visual representation of the book. It was in embryonic form, but that was the first time I saw what it could look like. There were these stills of what a scene in the Town House could look like. It was almost like reading a beat-for-beat graphic novel of the book, and that was exhilarating. I probably had very little feedback on anything having to do with the pitch deck because I was in awe of it.

What were the specific images that convinced you?

Green: There were these images of the guys in the Town House, and I remember there being a lot of bar scenes scattered throughout. That was always on my mind while I was working on the book ÔÇö one of my top-line goals was not just to tell the stories of the men and the stories of the period, but to really give the reader a sense of what it was like to move through those spaces in almost mind-numbing detail. I felt that itÔÇÖd really never been done before, at least in book form. To actually see it was a kind of emotional thing. IÔÇÖd spent a lot of time in the Town House, but obviously, IÔÇÖd never gotten to be in Five Oaks or some of the places in Philadelphia. That was a lost world, and the possibility that the documentary could recover that was really exciting.

I was going to ask you about the re-creations because theyÔÇÖre a standard of this genre but are often done so terribly. What was your concept for the Last Call re-creations?┬á

Caronna: I was terrified. It was the thing we shot almost last ÔÇö I knew I wanted them to live in memory, to be atmospheric and play with focal points, and to have all these wide pushbacks and pullbacks to use that Vertigo, Jaws vibe and make all the spaces feel like theyÔÇÖre breathing. A really good friend of mine, Ashley Connor, sheÔÇÖs an incredible DP, but sheÔÇÖs so busy that she couldnÔÇÖt do the project in the early stages. A week before we were going to shoot the re-creations she had the time, so we locked her in and figured out how to make it not look like everything youÔÇÖre talking about.

Howard and I came to it from the lived experience of being a queer person. IÔÇÖd been to Town House so many times, and I wanted to show the intimacy thatÔÇÖs there, the closeness of those spaces. It was so important to me to see not just queer joy, but also the intimacy that happens in these tiny queer bars when no one is watching.

Green: I donÔÇÖt know who I said this to at the outset of the project, but I said, Please donÔÇÖt do any re-creations and donÔÇÖt do any drone shots. I had seen so many documentaries where it was gratuitous, and it was always a sign that they didnÔÇÖt actually have the material to make the film. It was sort of humiliating to watch the finished project and realize, Oooh, this really works. The drone shots serve a purpose to show spatially where everything took place. I was like, Okay, I was wrong!┬á

True crime docuseries also tend to struggle with developing and following a clear timeline. What was your approach to that here?

Caronna: The book was the blueprint. Howard and I led with the Trojan horse idea that we wanted them to get as much queer history as possible, but it also had to be really compelling. Not just a history lesson of anti-queer violence, but keep them sitting through four hours of true crime. That was No. 1. And then, as we did interviews and fleshed out more of the story, Tony Marrero became more a part of the series. We had an incredible co-producer, Meghan Doherty, who found the family and got them comfortable, and then that became a whole episode. It wasnÔÇÖt in the pitch deck.

Green: As with the book, you make assumptions about what you want and then it never works out. What separates a good book from a bad book, or a good documentary from a bad documentary, is that the people working on it are nimble and can react to those changes in what is possible.

Were there other big moments of surprise during the production, things that caused you to reconsider your original plans?

Caronna: There were things at the beginning I knew I wanted. The conversation about how political rhetoric can turn into violence ÔÇö the whole time, I was like, that is the thing I want to drive home. But we knew less about Marrero when we started. I had known Cayenne, who speaks about knowing Tony in the docuseries, for years and years. I knew sheÔÇÖd been a sex worker working out of Port Authority around the same time he had been. I called her and asked if she remembered anyone named Anthony. She said the name was familiar but wasnÔÇÖt sure. I got off the phone and sent her a picture, and she immediately called me back like, Oh my God. So it was a lot of the stuff around Tony, and also Tracey OÔÇÖShea, the daughter of one of the victims.

Green: After the interview was done with Tracy, it was so good that it affected the editing of the rest of the series. I had interviewed her once on the record for the book, just 45 minutes in a downtown Panera. But she sat for hours and was so expansive ÔÇö it upended things in a good way.

I wanted to ask about one particular moment in the series, when one of the police officers who investigated one of the murders asks you, the director, why the interest in this case is always focused on gay life.

Green: Anthony can vouch that was my favorite moment, even from the rough cut.

Caronna: I remember as soon as that happened, we had a moment outside in the hallway afterward being like, that has to be episode one. I knew pretty quickly it was a moment. I never went into interviews with investigators with any kind of agenda. Everybody knew the angle we were talking about, and weÔÇÖd had many conversations. There was a surprise to be asked that question after so much conversation about why the gay element was so important.

Green: And heÔÇÖd read the book!

Caronna: With all the investigators, there are cultural awareness gaps when you donÔÇÖt know a community, and youÔÇÖre just worried about being a crime solver. They still donÔÇÖt understand the community, and itÔÇÖs at the heart of why this investigation went awry.

Green: I interviewed a lot of the investigators for the book, and my feeling was that I was using them to tell a broad outline of the investigation, but also because they remembered sources who were helpful in fleshing out the victims themselves. But I would say that my portrayal of the investigators in the book is basically neutral ÔÇö I let them be themselves, for better and worse. I appreciate that the documentary is not neutral. ThatÔÇÖs the great thing about it not being my project. It has a sensibility that is not mine, even though I share it.

There was so much care put into the process of this docuseries and so much thought about the genre more broadly. What do you hope viewers ask themselves about other true crime projects after watching this?

Caronna: Creators of true crime have a responsibility to the victim and a responsibility to not lean into the most salacious version of a story. We can choose to not create more damage with the content weÔÇÖre making. IÔÇÖm hoping true crime can come from a place of sensitivity rather than, WhatÔÇÖs the most gripping story?

Green: With the caveat that this project was a perfect storm of quality ÔÇö┬á not every project can be this good ÔÇö I hope this shows other artists, filmmakers, people working in this space, that itÔÇÖs possible to attempt something beyond the cookie-cutter approach of the genre. Not only that it can be attempted, but that it will be embraced, and the stuff people embrace is the societal aspect, focusing on the victims and families, the very stuff the genre has historically ignored.

This interview has been edited and condensed.