In the opening scene of Lee Pace’s first major screen credit, 2003’s Soldier’s Girl, his character Calpernia Addams introduces herself in voice-over: “You may think that I’m the center of this story—the main character, as they say—but I’m not.” The film is based on real events: Calpernia is a trans woman who falls in love with an infantry private stationed at Fort Campbell, and her first lines are at least a touch disingenuous. You wouldn’t need to say them unless there was some tension over who the center was. “I admit I’ve always craved the spotlight,” Calpernia says. “I’m the rhinestones of this story.”

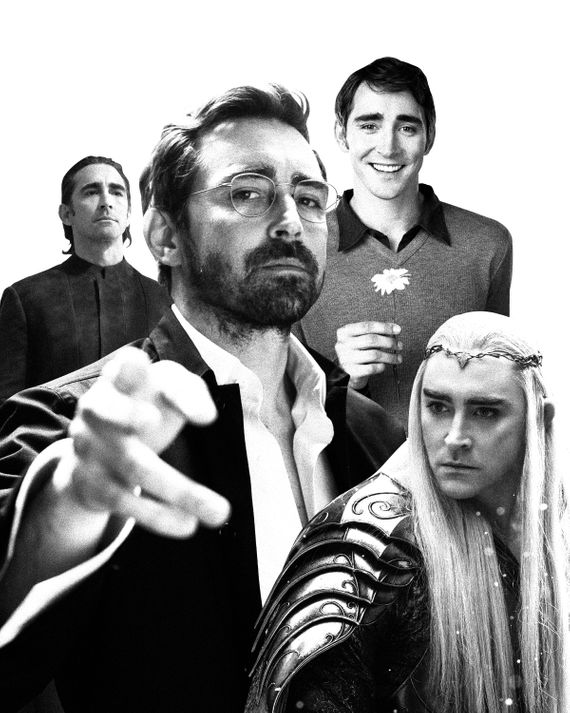

This year, Pace received the third annual Vulture Festival Honorary Degree, a very unaccredited honor given to those whose work we like so much we just have to give them a prize. Since Soldier’s Girl, the actor’s career has taken off in TV, in film, and onstage—as Roy in the indie fantasy film The Fall, Ned in the fairy-tale-esque ABC series Pushing Daisies, Joe Pitt in Angels in America, and as part of an ensemble of ’80s tech entrepreneurs in the show Halt and Catch Fire. Last summer he played Greg, Rachel Sennott’s mysterious older boyfriend, in Bodies Bodies Bodies. Pace has become known not just for his acting work but for his ability to elicit an overwhelming thirstiness from his fans. In a profile for the Cut last year, Pace was asked about the intensity of fan response to his Instagram. “I am aware,” he says; in accompanying photos, he stares at the camera, half-inviting, half-opaque. In August, GQ published a story headlined “Welcome to Lee Pace Summer”; last year’s Esquire declared “The World May Be Ending But At Least We Have Lee Pace.”

Even so—even with the charisma and talent of a leading man—many of his most notable roles have come from stepping into a small part inside a huge franchise and delivering a performance just on the right side of distractingly magnetic. See his role as Thranduil, the elf king in The Hobbit. That movie trilogy can feel overlong and leaden, yet Pace brings an otherworldly cattiness, a glowing well of petulance that cuts through the soppiness. “Unaccountably hot guy begrudgingly agrees to participate in someone else’s story”—this version of Pace has juice. It has friction. Thranduil nearly unbalances the movies with the pain of his buried grief and his deep longing for vengeance. His eyes glitter as he looms over the grubby dwarves who need his help. Yet it’s impossible to imagine a stand-alone Thranduil story—a protagonist with that much dazzle and spite would be exhausting. These kinds of roles reveal something paradoxical about Pace, the performer: He becomes more visible when seen from the side.

His most exciting lead performances are built out of the same dissonance. He’s best as a protagonist at odds with his own centrality, one who cannot stop obsessing over someone else. Calpernia claims not to be the main character of Soldier’s Girl; she keeps insisting we look elsewhere. But her love transforms her into the person we most care about. Pace played that role (and won a Breakthrough Gotham Award for it) a decade before shows like Transparent cracked open the conversation about cis actors playing trans characters. In retrospect, the fact that he chose to take it on feels like a notable first step toward his performances in works from the queer canon—including on Broadway, in The Normal Heart and Angels in America. When he came out to the press himself, it was only after years of instinctive, self-protective hedging in interviews about his sexuality.

In Pushing Daisies, arguably the role that turned him into a heartthrob, Pace plays Ned the Piemaker, the show’s straight man. (A wry twist for a show chockablock with metaphors for gay longing.) Ned is a simple, unassuming person who happens to be in love with a dead woman he’s brought back to life and now can never touch again, or he’ll kill her. He is so in love with this girl, who is named Chuck, that he can barely function. Pace transmutes that pain into something lovely, as though the planes of his face were reshaped solely so that Ned can smile wistfully at the one he adores. Beyond that, he clings to every scrap of a normal life he can find, fighting through an avalanche of oddballs: private investigators, one-eyed agoraphobic aunts, taxidermists and nuns and beekeeping murderers. Pace is never allowed to go as big and goofy as his co-stars. What makes him so irresistible is the way he absorbs and reflects them all anyway.

His role as Joe MacMillan in Halt and Catch Fire is built from a darker inversion of that same formula. Joe MacMillan is a striver, a salesman and visionary who wants to be the most special person in his world and hopes no one will realize he’s making it up as he goes. He walks into the series assured, a Don Draper in a world of people who just don’t get it. Over the show’s four seasons, Joe is brought low, again and again, by the realization that he himself is not the thing—he’s the thing that gets other people to the thing. He can see genius, but he cannot achieve it. He swings from acceptance to righteousness and back, surrounded by people who have the qualities he wants and does not have. Pace knows how to play debilitating longing. The role may be his best.

Pace is also a consummate performer of his own life. He gives interviews, occasionally. He posts photos of himself, sometimes. The best-known facts about his personal life are concrete details: He lives on a farm in Dutchess County, New York. He built a house there himself. He has a dog named Gus. He is both Rugged Outdoorsman and High Fashion Aesthete. All of that is suggestive of the kind of person Pace might be inside—so suggestive that it’s easy to forget that it’s only a suggestion. You cannot thirst for something you have plenty of.

This matches what may be his strongest quality as an actor: his withholding. Pace’s stare can feel like a tractor beam. You can’t see all of him, but it feels as if he sees you. Pace’s greatest trick is that he makes everyone in the audience feel like the main character. Watching him, we see ourselves as the objects of his regard—and we feel worthier and more appealing because of it.