In the course of a long and varied career, Mark Mylod has directed episodes of Entourage, Once Upon a Time, Shameless, The Affair, and Game of Thrones. He brought all that experience to bear on HBO’s current network-defining hit Succession, which he also co-executive produces with series creator Jesse Armstrong. Mylod is responsible for maintaining and evolving the look and sound of the series, the pilot for which was directed by Adam McKay (The Big Short); over the past three seasons, Mylod directed 12 of Succession’s 29 episodes, including the final two episodes of all three seasons.

The eighth and ninth episodes of season three — a two-parter revolving around the third marriage of Lady Caroline Collingwood (Harriet Walter), ex-wife of Logan Roy (Brian Cox), in Tuscany — pushed Mylod, the actors, and the crew in ways they never could have imagined at the end of season two. These episodes were the culmination of the first season of Succession to be produced under COVID-19 pandemic protocols, and they reconfigured the Roy family’s relationships in a way that decisively changed the dynamic between parent and children, setting the stage for the show’s endgame (whatever that turns out to be).

We spoke to Mylod about the process of directing actors as they perform emotionally wrenching scenes, the aesthetics of shooting with handheld cameras, the logistics of working with 35mm film in a digital era, and yes, that notorious New Yorker profile of series co-star Jeremy Strong.

I wanted to start by asking you about the performances — particularly how you shoot them and how you get these actors ready. The finale is an emotionally wrenching episode. These adult children are realizing their dad doesn’t care about them at all.

And the mother doesn’t either. Mom and dad both sold them out.

Can you just throw the actors into the middle of all that? Do you even have a choice given the realities of a TV production schedule? Do you do rehearsals? I’m curious about the process for the performers and for you, the director.

Are we talking specifically about the end of the finale and how we build to that?

I’m speaking specifically of the scene in the alley with Kendall in the dirt. And also the subsequent scene where, emotionally as well as physically, the positions are reversed, and it’s Roman who has basically collapsed, and then Shiv gets the “Kay at the end of The Godfather” treatment where she’s looking through the open doorway at her dad glad-handing her husband and realizes that he sold her out.

It starts from the writing. The road map emerges from the writers’ room. And therefore, obviously, we know where the season starts. We made the choice a long time ago that we would begin the story of season three moments after season two ended. And we knew that we would build to a point where Matthew’s character, Tom, betrayed Shiv. And that Kendall’s efforts to bring the siblings together in episode two would fail. And that through this extraordinary arc, eventually he would — or rather Shiv would — actually bring the siblings together. Despite that terrible betrayal of Shiv by Tom, you could argue that, in a way, she had that coming because she’s treated Tom so badly. Being double-crossed by her parents, the brutality of that … it’s all just a lot.

Oddly, I come out of the season finale not quite full of hope but with hope. Because for the first time, I think, in many years, the siblings are genuinely united. They understand family in a positive sense.

Because we shoot the story in order, and because the script evolves so much beyond our initial road map, by the time we get to episodes seven and eight and nine, everybody’s been on this journey, the actors especially, inhabiting those characters. We’re all a team. You know, about 90 percent of us have been working together since season one. So when it comes to shooting Kendall’s breakdown and everything that follows, we all know where we’ve been in order to get there, and we all know what’s required. As a director, my job at that point is to set the scene where I know the actors can excel and know their specific processes. I also have to know how I can best support and guide them and photograph the scene in a way that will reflect the enormity of the emotional content.

The scene in the alley, especially, is an extraordinarily vital scene, not just for the episode but for the season and to the show as a whole. The potential for mistakes was high.

It’s unusually still for a scene on Succession. This show jumps and dances around a lot visually. Here, comparatively, things are more rooted. It’s as if the camera is paralyzed at how horrible it all is.

A lot of those choices are kind of unconscious and intuitive. It just felt right to say, “Okay, can you walk down here? And you’re going to start talking about here.”

I laid a booby trap for Jeremy. We didn’t tell him we were going to have two or three of the kitchen staff come out with trash bags and put them in the bins because I knew that would create a reaction that would hopefully be helpful to him.

So you knew, based on having worked with him, that Jeremy was going to see the kitchen staff with the trash bags and go, “Oh my God — those guys are like the waiter I killed,” and use it?

Yes.

It’s great when you have that level of understanding with your actors.

They’re an extraordinarily intelligent cast, every single one of them. And I know that Jeremy appreciates and feeds off spontaneity and unexpected stimulus because he’s so in the moment — all three of them are. We knew that would be a helpful trigger to get him to this incredibly hard place. And then it becomes about blind intuition.

It was hard for physical reasons. It was burning hot out there, and it lent what became a wonderful kind of T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” feeling to it. And the gusting wind coming up was blowing up the dust!

I was reminded during that scene that you were in Michelangelo Antonioni’s home country and that these were the kinds of privileged, depressed characters he’d have told stories about — though without all the incest and patricide jokes.

Exactly. And we were able to mine all of that visually.

Kendall’s even got a bit of Red Desert on his ass at the end of it.

That’s why I chose that location. It was that dustiness, and it was 100 yards away from the beautiful green glamour of the wedding, but it felt like a different world. We could put that new, harsh light down on the characters, and they’ve got nowhere to hide.

Once you’ve figured out the basics, it becomes a take-by-take thing. After every take, we had to stop and wash poor Sarah’s eyes out because so much dust was blown in during the shooting. We’re just trying to find a genuine moment. And it happened on one take, where Roman comes up and puts his hand on Kendall, and it just unleashed Jeremy.

How did it feel, the moment when that happened?

I think Jesse and I, just watching as fans on the monitors at that point, felt this collective punch in the gut at the emotion of that moment. And also real, huge relief because now I know we have the scene. We have that ultimately cathartic moment we needed. The stakes really were so high that I feared the scene might fall short of its potential if we didn’t have an authentic moment of connection, however twisted it turned out to be in the dialogue — yet also authentic to the character of Roman, a person who can only give sympathy through sick jokes.

But returning to your question about the staging of the scene, the emotion of it, the stakes — that’s why, when the call comes in from Laird, I asked Sarah to go to a spot in the background because I knew I could keep this very still shot. So your observation is completely correct: I was trying to stop the camera from moving too much and hold as much as I could in that three-shot.

When you’re going through a scene like this and the actors are crying their eyes out, do you do the entire thing from start to finish several times? Or do you break the scene into sections and do them one piece at a time?

I rarely if ever break up a scene. In three years of directing on the show, I can’t think of any examples where I’ve broken a scene up, no matter how long the scene is. Sometimes that means we’re barely getting the scene in before the film roll runs out, but I still don’t break it up. We run it like it’s a piece of theater.

So you stage it like a play and then cover the play as a documentary cameraperson?

That’s exactly it.

Do you have a particular strategy with regard to how you shoot the performances?

We’re working with two cameras and always starting with close-up performance. If there are wide shots, I’ll shoot them later, when everyone’s exhausted.

Is it usually the same two people every time? Or do you change them up?

Typically our two brilliant camera operators are Gregor Tavenner and Alan Pierce. Alan was unable to travel to Italy with us for the last two episodes, so Ethan Borsuck, our first-assistant camera operator, stepped up to operator for 308 and 309 and did a fantastic job.

There are a lot of different ways to shoot handheld. What is the aesthetic here?

Hopefully it’s handheld without looking too handheld, trying not to draw attention to the camera too much. We want all the imperfections of slightly bad eyelines, of not quite getting the moment. It’s the imperfections that are so important to us.

One of the questions we deal with in successive seasons is how to keep that roughness. I’ve worked on productions for multiple seasons before, and if you look through any television show, almost universally it’ll start out one way, and it gradually evolves in many cases to a more generic, crafted place by season three or four. That’s because we’re programmed to make things look good in a million tiny ways. So things get a little slicker, more curved, with smoother edges. One of my roles as a producer-director is to protect that messiness because the messiness lends authenticity to the moments.

So did you all come up with a plot for the finale and then say, “I’ve never been to Tuscany. Why don’t we shoot this in Tuscany?”

[Laughs.] Actually, yeah. There was a bit of truth to that, to be honest.

“Well, we need to go to Tuscany for this story to be believable.”

The broad answer is there was a bit of a joke going around in season one about where to shoot Shiv and Tom’s wedding. Jesse and I, at that stage of our working relationship, were slightly dancing around each other more than we do now, outpoliteing each other. And I made a big pitch for Morocco to be the venue, and Jesse was like, “Yeah. Hm.” Which I now know to translate as “That’s a fucking terrible idea. Never mention it again.” But at the time, I took it more literally, so I spent a glorious week researching various palaces in Morocco for this grand wedding and then did this picture presentation to Jesse, and he was like, “Good. Yeah. Nice.”

And then at some point, he came to me and said, “I think it should be in Wales.” To me, “Let’s shoot it in Wales” is like “Let’s shoot it in New Jersey.” The idea of shooting this billionaire’s wedding in rainy Wales in February and March was depressing to me, but he specifically wanted to write somewhere he knew. He grew up very near there, in Shropshire, and he felt he could write the local characters with more authenticity. So yeah, I lost that one.

For episode eight of that year, Tom’s bachelor party, we’d always talked about that being on a yacht, but we couldn’t afford it then. So put that aside: “Well, maybe if we get a season two, we’ll pull that one out again.” And of course, we eventually did and found this “who’s going to be thrown overboard” metaphor that justified us using a yacht at the end of season two.

The other fantasy place we proposed to shoot was Tuscany, and beyond it being part of our personal wish list, Chiantishire to the English is a cliché place for somebody like Caroline and, certainly, Peter, her fiancé and eventual husband. It was just the right place for people of that class. We had a birthday party for Brian while we were out there, and Sting came out there with Trudy, his wife. A lot of people are spending more and more time out there now. It’s incredibly intoxicating. The COVID of it all made the Italy bit insecure for a long time, so the other idea was to shoot Caroline’s wedding in North America, which was depressing the crap out of all of us because we couldn’t land on a place. Maybe Martha’s Vineyard? We just knew it had to be a place where, legitimately, we could imagine somebody like Caroline going for her wedding. We also discussed going to the Bahamas or somewhere in the Caribbean, but we couldn’t afford that.

Would you ever consider doing what a lot of film and television people do, which is pick a place where you can pretend you’re somewhere you’re actually not, like when films shoot in Toronto and pretend they’re in New York?

We did have that discussion, specifically about shooting the Tuscany sequences in Napa Valley in Northern California, but the problem is the architecture doesn’t match. And we’re not good at faking it, even if there’s more than a century of film location cheating. There’s not necessarily a legitimately rational reason for us rejecting Napa Valley other than our obsession with authenticity and how a place feels to us.

What other authenticity discussions do you have on the show?

There was a big argument, or debate rather, prior to season one about whether to shoot digitally rather than film stock. We fought hard to stay on film stock. There’s an argument that on the television screen, you could barely tell the difference. In fact, we did a few tests and put grain into digital images. But it just felt more authentic to be on film stock considering what kind of show we’re making here.

I always thought there was a philosophical justification for shooting on 35mm film stock with handheld cameras because it seems so … not wasteful, but extravagant? And this is a show about extravagant people.

The production process for 35mm is more involved, it’s true. And HBO is incredibly generous in the way they support their programs, budgetarily and creatively, obviously. But shooting on film wasn’t intended as an extravagance. There’s something about the way we work with improv takes — what I call “freebies” — where the looseness of the staging means that shooting on film acts as a counterpoint. The discipline of having a 1,000- or 400-foot roll of film that limits how long you can go focuses everything. I know that feels like a thin argument, but it gives us a structure we really need.

Can we talk a little bit about the reaction to the profile of Jeremy Strong in The New Yorker? A friend of mine said of the finale that you could argue about Strong’s process, but not about the results. But there was also a sense from the piece that his process is quite a lot for the production to deal with.

Every actor of any quality that I’ve ever worked with has a unique approach. I think Jesse put it well, saying something like, “Whatever gets you through the night,” the John Lennon quote. And I’m with him on that. I don’t really have anything to add beyond that. I have nothing but respect and adoration for all the cast. I want them all to feel supported. As to how that’s manifested in the press, that’s just not something I ever want to get into, to be honest, Matt.

I’ve read quotes to the effect that this is going to be a four-season show, maybe five. Does that seem accurate to you at this point?

Yeah. There are discussions about that. And the answer is solely with Jesse. He will keep telling this story till he feels he doesn’t have more story to tell. I’m sure they’ll convene again in the writers’ room next month and start putting together the building blocks for the next season, and that process will continue until at some point Jesse will say, “I think we’re done.” And I genuinely have no idea when that will be.

Were you surprised by the reaction after the final shot of the penultimate episode, when viewers were basically saying online, “Oh my God, they killed Kendall”?

We made it to a South Park comparison! I don’t want to sound coy, but I don’t tend to read a lot about the show. Obviously, we intended it as one element in our version of a cliffhanger.

But then you pick that thread up at the very beginning of the next episode and it’s like, “Yeah, he’s fine. He’ll be coming over here in 15 minutes.”

[Laughs.] That’s what I mean when I say, “That’s our version of a cliffhanger.” I’m almost glad that final shot caused a stir. I’m very proud of that shot.

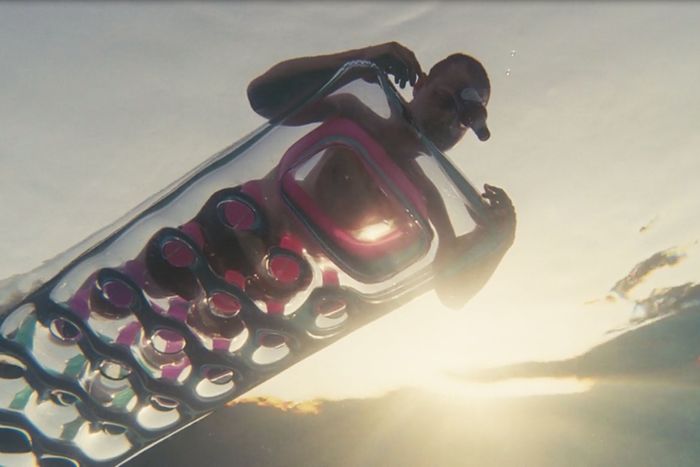

With the cameraperson on the bottom of the pool, obviously.

Yeah. Pat Capone did a brilliant job, as ever, and Jeremy timed it beautifully with the bottle coming down and the bubbles. It was a really nicely crafted moment.

You don’t hold shots that long, normally.

No, never. But that shot kept giving and giving, so we held it longer than we normally would.

How many takes did you do of that shot?

Very few.

Did the bottle always fall that nicely?

Yeah, it really did, it never once sank. The one you ended up seeing was the best of them. That was the one that lasted the longest. We specifically chose this transparent floatie for Jeremy because I hoped that if we got the angle of the sunlight right, it would do this incandescent spreading of the light.

Do you have any particular film moments in mind when you do a shot like that?

Not really. Somebody mentioned Gatsby, but it wasn’t something I had in mind. It’s not really my way to think, Oh, I’ll do a little D.W. Griffith here. If it happens, it’s because I’ve unconsciously ripped somebody off without realizing it.

I remember getting a load of comments from my work on Game of Thrones when I had some oranges tumble down some steps. The Godfather is one of my favorite films, but suddenly there were all these people going, “Oh, oranges, it’s a symbol of death from The Godfather,” but truly, it just seemed like the right choice intuitively at the time. Was it a Coppola homage? Maybe, but not consciously.

Tell me about shooting during COVID.

Shooting with COVID was fucking miserable, man. It really was. It’s horrible. To the best of my knowledge — with the exception of poor Mark Blum, who played Bill, who died in the early onslaught of COVID — our cast and crew and their families were relatively okay. I don’t know of any other deaths in our extended work family.

Our problem with COVID was that it made things so damn transactional. When we started shooting episodes one and two, which I also directed to kick off the season, we eventually got going around Thanksgiving of a year ago, 2020. We were originally due to shoot in March of that year, but of course, COVID closed us down.

Everybody on set was masked and wore face shields and at a minimum six-foot distance. And it just had to be that. So after two glorious seasons of whispering and close, tactile proximity to this amazing cast, suddenly I’m projecting to get heard over the plastic face mask. All the nuance and enjoyment in the process was really taken away for me. I think everybody found it incredibly hard.

We’re more used to it now, living with the knowledge that there have been 800,000 deaths and still counting. And HBO, I’ve got to say — and I don’t mean this to be kind of corny or bum-licky at all, but — the resources and support they put into keeping cast and crew safe with on-set protocols and a stringent testing regime were absolutely extraordinary.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic change how you chose the locations and blocked the scenes?

You will note that episodes one and two, with one or two exceptions, are very small episodes. Episode three was also small, with the exception of the press gathering and the awards at the New York library, which we found very hard to shoot. Episode four, tiny. It’s only when you get to episode five that there’s any scope. And even then when we did those big group shots in the hall of the annual meeting, we were really careful about social distancing and using visual effects to fill in the people there.

Oh, so you filled out the crowd digitally?

Yeah. We didn’t feel confident in having that many background people. The background actors we hired for this season were all tested before they came on set and throughout the process. It was only when we got to episodes six and seven that we scaled up in terms of the number of people we felt comfortable putting into one shot. And luckily by the time we got to Lorene’s episode, Kendall’s birthday party, we were able to go big. But even then, she had to be very careful with their staging. She did a brilliant job because the event feels huge even though it was shot very tactically.

Where do you think empathy comes from when, no matter who you are, the characters on this show would ruin you and then cover it up if it suited their purposes?

My theory is that as season one progressed, and we got toward “Austerlitz,” the seventh episode of season one, we started seeing the emotional underbelly and the vulnerability of the characters. As we as storytellers got to show more of that vulnerability and the audience got to understand the context of the characters’ behavior — not forgiving their behavior, but having the context of that gilded cage that they’re all so miserably trapped in — it became a little easier to sympathize on a basic human level of, That person is in pain. That person is trapped.

And then, of course, you have the flip side, a classic eat-your-cake-and-have-it scenario: When they behave despicably and bad things happen, you can enjoy that vicariously as well. So you kind of have it both ways.

There are times on Succession where important dialogue is spoken and you don’t see the person saying it. Instead, you focus on the person hearing it. What’s that about?

First of all, it comes from a blueprint that goes right back to Adam McKay directing the pilot. He captured moments. There was imperfection to it. And that imperfection is something that I really tried to keep.

In terms of the why, it just seems like the right style to capture something that is happening — not something that’s been staged for us and that we have control over. It’s not quite documentary because the camera would be too much of a presence in the room — too much of an influence and too subjective. We’re trying to give the sense that we’re barely keeping up with things that are happening beyond our control. Also, a lot of the time, the most important or illustrative moment can be found by focusing on the reaction to hearing words as opposed to the person saying them.

What is Brian Cox like to work with and be around? I get this impression from reading interviews with him that he’s blasé about things that would be mind-blowing to most people.

That’s exactly it. Whatever the opposite of pretentious is, that’s Brian. But there’s a lovely thing about Brian, which is that he does that “been there, done that” thing, but whenever there’s a big scene, I’m friggin’ terrified when I’m walking up to that set because I don’t want to fuck up such brilliant writing, and I see exactly the same look in Brian’s eyes. No matter how many decades he’s had in the business, and no matter what an incredible, storied career he’s had and all the success he’s had recently playing Logan, he still comes to work as hungry as fuck. The work ethic and commitment he displays at this stage of his career is astonishing.

Did you find him intimidating at the beginning?

Heck yeah! It took a while to get past that for me. He can still be very intimidating. He’s an extraordinary presence.

Even now, after three seasons?

Yeah. I have to keep my chin up because he’s a force. Brian acts like No. 1 on the call sheet in the best way. He advocates for the rest of the cast. He is that paternal character to us all. And he will give me feedback. He’ll give the production feedback. “Hey, I see you’ve pushed their call this time. What’s this about?” He keeps an eye out for other people, and he’s incredibly tuned in and looks after everybody. He’s a truly good human. He really is.

He’s playing a bad dad on TV, but he’s acting like the good dad on set?

That’s what he truly is. It’s a beautiful irony. Isn’t it?

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.