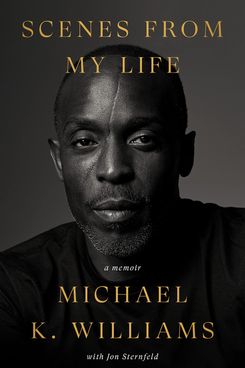

The world will never stop missing Michael K. Williams. The following excerpt from his posthumously published autobiography, Scenes from My Life, is a keen reminder of why. The beloved actor and costar of The Wire, Boardwalk Empire, and Community was in the final stages of finishing the manuscript, which was co-written with author Jon Sternfeld, when he died unexpectedly in September 2021 of a drug overdose. Williams’s cool rasp leaps off every page, his story told in the direct yet impassioned language that defined his greatest characters.

Scenes from My Life begins with Williams’s tough childhood in Brooklyn’s East Flatbush neighborhood and continues through his teens and 20s, when he discovered his love for dance and acting and began honing his skills, trying to land any job he could. As Williams moves through his life — its stages built around scenes, as in a movie — the book takes in the full breadth of his experience, alternating stories of struggles with addiction, tales out of school from the sets of films and TV projects, loving recollections of family and friends, and community activism aiming to reform the criminal-justice system.

The centerpiece is, of course, Williams’s career-making performance as The Wire’s Omar Little, an openly gay stickup artist who relieves Baltimore drug dealers of their stashes and money when he isn’t doting on lovers and bantering with police detectives who know better than to assume they can outsmart him. In the excerpt below, Williams talks about the real-life inspiration for Omar, recounts the day he auditioned for the role, and goes into detail about all the research and training he did with both hired experts and colorful figures from his own life to make the character believable. Williams’ description of how he visualized Omar — what made him so effective as the character — could double as a characterization of Michael K. Williams, actor and man:

“Omar is sensitive and vulnerable and he loves with his heart on his sleeve. You can say what you want to him—it rolls right off—but don’t you dare mess with his people. He loves absolutely, fearlessly, with his entire being.”

Excerpt from 'Scenes from My Life: A Memoir'

If it looks real to you, it feels real to me. On The Wire, Omar’s tenacity and swagger were based on people I knew and grew up with — including Joanie’s brother K — and Robin. But his pain, his raw nerves, I didn’t have to look anywhere for that. I was built out of that stuff.

Omar Little was described as a guy from Baltimore who robs drug dealers, though he doesn’t sell or use. He’s gay, doesn’t hide it, and operates as something of the Robin Hood of his community. My habit for auditions at the time was to go dressed as the character. For the Wire audition, which [casting director] Alexa Fogel put on tape in her office, I wore a pair of my Sean John overalls over a New Jersey Devils hockey jersey, which Robin let me borrow. The scene was the one where me and my lover, Brandon, are followed into the graveyard by Detectives McNulty and Greggs. (I wore that exact same outfit when we shot the scene.) The scene shows Omar’s power because even though the cops are following him, he’s the one who leads them there. He knows they’re tailing him and brings them there to have a parlay — on his own terms. I was channeling Robin there, her bravado, the ease with which she did not give a fuck. In later years, I loved telling people that one of the inspirations for Omar was a beautiful lesbian girl from the hood.

Alexa talked about how the goal for the actor on camera should be to condense all of your energy and have it ooze out through your eyes, like a pressure cooker or a steam kettle. The goal is to keep the intensity there, and let stillness be your best friend. Your face doesn’t need to do too much because the camera will pick that up. On the show, when Omar was on-camera in extreme close-up, chin to forehead in the frame, I’d go as still as possible, so any little thing would jump off the screen.

If I’m honest, at the Omar audition, I was so beat down emotionally that the stillness came from somewhere else: I was just dog tired. I had given up and didn’t care anymore. That’s the most ironic thing. That exhaustion, that fuck-the-world attitude, helped get me the part that would change my life.

To play Omar, I tapped into the confidence and fearlessness of people I’d known growing up. I borrowed from the projects, even asking K— to take me up on the roof of my building at Veer to teach me how to shoot a gun. I’d held guns before, but never in preparation to use one, and I didn’t want to be one of those dudes holding their gun all sideways. Concerned about my tiny wrists I asked K— to show me the proper way to hold one. “So, do I use two hands or one?” I asked him.

“Nothing to do with your wrist size,” he said. “You definitely want to use two hands, because that’s how people who know how to handle a gun do it.”

We shot at the roof’s steel door, the echo exploding into the air, the force of the recoil surprising me. We started with a 9-mm., a small but powerful gun, with a kickback strong enough to knock you down. Then we used some bigger ones. K— taught me how to cup the bottom, how to use the sight on the top of the barrel, how to aim below your target because the kickback will raise you up enough to hit it. I practiced at it, over and over. Omar had to look like a guy who knew how to use a gun. Without that detail looking real, nothing else would have flown. You can have the whole neighborhood yelling, “Omar coming!” and running for cover, but if I walked out there holding that shotgun like I didn’t know what I was doing, I’d get laughed off the screen.

As for Omar’s homosexuality, it was groundbreaking 20 years ago, and I admit that at first I was scared to play a gay character. I remember helping my mother carry groceries to her apartment and telling her about this new role that I booked. I knew from the jump he was going to be a big deal. “This character is going to change my career,” I said. “But the thing is …” I hesitated. “He’s openly gay.” My mother is as conservative as they come, and I worried she would not be behind me at all.

“Well, baby,” she said, “that’s the life you chose and I support it.” She hadn’t embraced the arts or my interest in them, but to me, that was her version of encouragement. I took it for what it was worth. I think my initial fear of Omar’s sexuality came from my upbringing, the community that raised me, and the stubborn stereotypes of gay characters. Once I realized that Omar was non-effeminate, that I didn’t have to talk or walk in a flamboyant way, a lot of that fear drained away. I made Omar my own. He wasn’t written as a type, and I wouldn’t play him as one.

After getting over my ignorance of guns and my concern about his sexuality, a new, more potent fear dug its way into my mind: This dude is a straight-up killer. He strikes fear into the heart of anyone in his path. But everyone knew I wasn’t that guy. People were going to be scared of “Faggot Mike”? They were going to run from “Blackie”? I was 35 years old when I started on The Wire but carried that scared childhood self close; he lingered under my skin, just below the surface. So the self-talk got fierce: There is no way you can pull this off. You have nothing to pull on. There’s nothing remotely you have in common with this guy. You don’t know how to make him believable.

The change came when I stopped trying to bring myself to Omar and started doing the opposite: I brought Omar to me. I dug into how he was like me, tapping into what we had in common. Omar is sensitive and vulnerable and he loves with his heart on his sleeve. You can say what you want to him — it rolls right off — but don’t you dare mess with his people. He loves absolutely, fearlessly, with his whole entire being.

After clicking with that, I understood him completely. I came up with the narrative that his vulnerability is what makes him most volatile. When he cries and screams over his lover’s tortured and murdered body, screaming in the halls of the morgue and hitting himself in the head, that looks real because it felt real to me. When Omar goes after Stringer Bell and everyone else responsible, he is driven by love and loyalty. Omar scared the hell out of everyone, but I played him as vulnerable, sensitive, raw to the touch. That’s what I tapped into about him. He feels. But he’s also an openly free human being who doesn’t give a rat’s ass what anyone thinks of him. And that gives him power.

I signed on for seven episodes, and considering Omar’s “occupation,” I figured he’d be done for after that. So I got serious. Shooting in Baltimore for season one, I was as sober as I’d ever been, barely even smoking weed. I treated the job like my life depended on it because in some ways it did; I came this close to not even being there. By that age, I’d been on the addiction/relapse merry-go-round enough to know how things could unravel once drugs entered the picture. I knew where they would lead me because it was always to the exact same place.

When I first got down there, I did my homework to learn the specific Baltimore accent. I remember sitting at a table at Faidley’s, in the back of Lexington Market, over some crab cakes, and just watching and eavesdropping on people for hours. I picked up the interesting phrases, the habits of speech, the way those vowels sometimes took left turns. Baltimore has this character, like a stew, that comes from being part North and part South. Some things come up from Virginia and the Carolinas (where my dad’s family was from), and some down from the Northeast. It all converged in Baltimore, meshed together, and became its own unique thing.

When I came out of the downtown market and — in broad daylight — saw addicts nodding out right at the corner of Eutaw Street, I actually thought it was a setup for a shot for The Wire. I didn’t know much about Baltimore, but that sight woke me up. It drove home what we were doing. I’d met some people, heard some stories, and learned that the life expectancy in the Black neighborhoods of Baltimore is worse than in North Korea and Syria. Part of my process involved walking around the hood to get a sense of what it was like, especially at night. I knew East Flatbush, but you can’t just transfer one hood to the other. I feel like too many shows and films just do “New York” when they’re trying to capture a certain kind of urban Black community. But David Simon and Ed Burns were definitely going for something specific. There are similarities — we’re all human — but the character and textures are different, and I aimed to absorb what I could.

One late night I was driving around that area with a friend — windows down, sunroof open — and I heard some dude yelling what sounded like “Airyo!” After the second or third time, I pulled up at the curb and called one of them over to the window.

“What is that?” I asked. “What are you saying? ‘Air-Yo’?”

“Where you from?” he asked.

“Brooklyn.”

“What do you say in Brooklyn when you call each other?”

“Oh!” I said as it clicked. “You’re saying ‘Aye yo’?”

So I worked that into Omar’s vocabulary. It’s like “Hey, yo” — but “Aye yo,” with a peculiar Baltimore r sound jammed in there that took some practice, as did Omar’s specific drawl. I got compliments from Baltimore people on that, and when viewers were surprised I was from Brooklyn, that meant a lot to me.

Accessing Omar required my getting into a certain head-space. Music had always been a portal to take me into a character, and I would put on headphones and listen to these playlists I made (Omar’s had Tupac, Nas, Biggie, and Lauryn Hill) that tapped into memories, emotions, places I wanted to access inside myself.

I found where Omar and I intersected, but he was also a fantasy of who I wanted to be. Not a thief or a badass, but an openly free human being who didn’t give a damn, who took what he wanted, who wanted without fear, who loved without shame, and who feared not a living soul. Omar became an outlet for Mike. I was picked on so much growing up, and felt like such an outcast as an adult, that playing someone who was liberated from that, liberated me. It’s why it was so hard to let go of him.

Once I put on that long black trench coat, lit one of those skinny clove cigarettes, and heard “Action!”, no one could lay a finger on me. Omar traversed his territory like it all belonged to him. Sometimes he snuck in through back doors of stash houses, while other times he just walked right down the middle of the street, whistling his signature tune. (The sound wasn’t me but a woman they dubbed in.) I always thought of it as “A-Hunting We Will Go,” though David Simon said it was “The Farmer in the Dell.”

I also loved how Omar is the opposite of the stereotypical hood types. He isn’t about the cars, clothes, and women. He doesn’t fit into any of the boxes people might try to stuff him in, whether that’s morally or sexually or something else. In so many ways, he stands alone. But he also feels pain, especially when his loved ones — Brandon and then, later, Butchie — are killed in these horrific ways. Both times the pain cuts even deeper since they are killed because of him, to send a message to him, because his enemies can’t get to him. That’s a particular kind of hurt.

A director calling “Cut” doesn’t erase what you’re feeling. Your mind feels the fictional the same way it feels the real. There are spaces in your brain — and your body — where there is no distinction between the two. If you activate trauma and pain, you don’t have control once it comes out. And it comes home with you.

That’s the flip side of getting into a character; you wake up that sleeping beast, those actual memories, those real emotions. I meditate on painful things all day long for a scene and when it’s over, it’s little wonder I’m tempted to go off and smoke crack. Drugs had long been a smokescreen, a cocoon, a means for me to hide from the real. In character, sometimes things get too real for me. More real than real, if that makes sense. I don’t “disappear” into a character; I go through him and come back out. But when I come back out, I’m not the same.

In regards to Omar and his lover Brandon (played by Michael Kevin Darnall), it seemed like everyone was dancing around their intimacy issue. There was lots of touching hair and rubbing lips and things like that. I felt like if we were going to do this, we should go all in. I think the directors were scared, and I said to one of them, “You know gay people fuck, right?”

At some point, the issue boiled over for me so I went to talk to Michael before we shot a scene. “Yo, Michael,” I said. “It’s time to step it up with Omar and Brandon.”

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“I’m thinking in this scene we should kiss.”

“Okay. But — that’s not in the script, though.”

“But it feels right,” I said. “Don’t it?”

“Maybe let’s run it by the director and see what he has to say?” he suggested.

“Naw,” I said. “I don’t think we should ask anyone. I think we should just do it.”

He was game. “Okay, but don’t tell me when you’re going to do it. Make it spontaneous so it looks natural. Just go for it.” They called us for rehearsal and the crew was still putting the set together, getting the lights and camera up while we ran through it. When I went in and kissed Michael on the lips, everyone stopped what they were doing and went slack-jawed. Twenty years ago, men — especially men of color — were not kissing on television. I don’t mean it was rare; I mean it did not happen.

The director, Clark Johnson, was on a ladder and he said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, hold up.” He wasn’t really watching the first time but just heard the lips smack and maybe sensed the crew’s reaction. “Do that again.”

We ran through the scene and kissed again. “You’re some brave motherfuckers,” he said. “All right, let’s get it.” The crew all stopped what they were doing and rolled action. I think he was anxious to get it before one of us changed our minds.

When I got my first scripts for season two and I saw the story line had switched to white workers on the Baltimore docks, I was livid. Probably with a little chip on my shoulder, I sought out David Simon, who had more than enough on his plate. “David,” I asked him, “I wanna talk to you. Can I come by the office?”

“Sure, Michael, come on by.”

To his credit, he heard me out. We had a conversation, and I told him my thoughts — about this being a Black show about the Black experience that foregrounded Black actors and now it looked like he was changing all that.

“You know, Michael,” he said. “I understand, but you need to trust me. If I lead off season two going back into the low-rises, it’s going to make your world seem very small.”

Of course he knew what he was doing, and eventually I’d see the big picture: how the circumstances of Omar’s world, his allies and enemies and victims, were connected — in some ways parallel — to the rest of the city’s institutions. But I’d be lying to say I got that right away. That didn’t come until I started watching season three.

At the time, I didn’t get it at all. What I got was high.

The blame rests on no one but me — my addiction is what it is — but the dark world where Omar resided was part of what led to my relapse. I also know that circumstance — more money and more time — played a role.

It’s like this: In season one, I was a recurring character, which meant logistically that for my shooting days, production would bring me in on an Amtrak train, put me up in a hotel, and then send me home when my work was done. Season one felt like: Make the most of it, make your mark. Don’t fuck this up. But when season two rolled around, Omar had become this breakout character and I was made a series regular (with a salary bump), so things changed. Logistically, I was required to move and live in the location of the production.

By then, I had fallen in love with Baltimore. That city just touched me. I’ve never loved a place more than Brooklyn until I moved there. My blood was there, and I had some connection that I can’t explain. But I was financially illiterate, so I thought I was rich. Never mind agent fees, manager fees, taxes, and so on. I rented a beautiful apartment on the first floor of a brownstone in a nice area of Baltimore: two bedrooms, two baths, a basement, backyard, fireplace, exposed brick. I filled it with all the furniture from my Brooklyn apartment. It was the best quality of life I’d ever lived, and I had given it to myself. That meant something.

I could’ve thought ahead, saved that money, and just gotten a small furnished room in Baltimore, but I wanted to go all in. That place felt representative of the commitment I’d made in my heart. I had hopes of moving there, making it my second home. At least I had the foresight to keep my apartment in Vanderveer and pay the rent for the year in advance. Later, when the season was over and I had to do my auditions in New York, I could have a little place to crash.

As a series regular in season two, I was getting more per episode and getting paid for every episode produced, whether I was in it or not. So I had more money and more time on my hands: It was the devil’s workshop. My demons had room to play. On days I wasn’t shooting I started getting high on crack and cocaine again and I rolled like that pretty much all year, until I was completely broke.

When season two wrapped, I felt the thud of coming back down to Earth. I could no longer afford the rent on that beautiful Baltimore apartment. Putting all my things in storage, I moved back to New York, to my empty Vanderveer apartment, which had nothing but a mattress on the floor and a milk crate to eat on.

Omar became a superhero costume I wore to hide from myself. I put it on, made it my own, and then let it overtake my life. The lines got blurry and it all went to my head. Everyone thought that I was him, and pretty soon, I was making the same mistake. Inside that long black trench coat, I felt invincible, protected from any threats from the outside and whatever was haunting me on the inside. Not only did I not have to be Mike, but I could be someone revered, feared, and beloved. Everywhere I went people wanted to buy me drinks, smoke me up, or just shake my hand. People confused me with Omar, which I became all too happy to accept, and then I confused myself. After I went home for the day, or even wrapped on a season, I didn’t change out of my costume. I wasn’t ready to get a look at what was underneath.

When I first left the cocoon of Vanderveer as a teenager, Robin had christened me Kenneth, a dude who was stronger and freer than Mike ever was. Now I had been renamed again, on a much larger scale, and I embraced the hell out of it. Omar seemed like the antidote, the answer to everything I had been hiding from. And what made all of it so much easier to feel like that was the drugs.

Cocaine was there when I was feeling good about the person I was pretending to be. Crack was there in my darker moments, when the seams started to rip, when I felt vulnerable and this voice would creep up on me, asking: When is the other shoe going to drop? When are they going to find out you’re a phony? When are all your secrets going to be revealed? When are they going to turn on you? Will they love you when they know who you actually are?

Being an addict means forward and back constantly. It means saying no again and again. That’s why someone who is clean for 30 years can still call himself an addict. They’re always one choice away.

One late night at a club in Baltimore, I was drunk at a table when I heard last call. Not wanting to wait for the waitress, I stumbled to the bar to get one more shot of Hennessy. Standing there, I looked over and saw someone who stopped me in my tracks. I thought, This is either a young pretty boy or a masculine-looking woman. I couldn’t take my eyes away. She was androgynous and stunning and her energy was the loudest thing in there.

“I’m a female,” she said, sensing what my question was. I thought she was beautiful and there was this magnetic pull coming from her, like we were meant to know each other.

“Okay, I got you,” I said.

“What’s up, yo?” she said, recognizing me. “I heard you were repping my city.”

Her name was Felicia. We got to talking and I encouraged her to come down to the set of The Wire for an audition. The Wire was always interested in authentic, and Felicia “Snoop” Pearson was as authentic as they come. She had lived that life, had scored in it, had suffered in it, and soon enough she was portraying the fictional version of it that was based on her own reality. I think I introduced her to the Wire co-creator Ed Burns, but the rest of her story is all on her — she’s a rare talent and powerful presence, as real as they come.

As she and I became friends, I learned more of her story. Born premature to a crack-addicted mother, she was raised in East Baltimore by her foster mother and father. As a teenager she worked for local drug dealers, was arrested at 15, and served six and a half years in a maximum-security prison. She was charged as an adult for second-degree murder for shooting a woman who attacked her with a bat during a street brawl. When she got out, she tried to go straight, but she kept missing out on or losing jobs because of the violent crime on her record. So she went back to making money in the streets, which is what she knew. Then we found each other. I know our lives were meant to intersect. Her presence on The Wire, the way it gave her a voice and a platform, was yet another thing about that show that was so much bigger than television.

As the years went on, I got out of my own head and came around to see that The Wire was bigger than Omar, bigger than Mike Williams, bigger than Baltimore or even just the Black community. David Simon knew what he was doing. The show, which added to its world each season, was creating a portrait of America.

I remember the day toward the end of season three when we shot the scene where Omar kills Stringer Bell. It ate at me, and I avoided Idris Elba, who played Stringer, all day. I was troubled by it, the message. Why is this the way two Black men settle their differences? It bothered me, especially since Stringer was making his way through college, setting up in real estate, trying to get out of the game. And I had to kill him.

I talked to the writers about it, about why that had to happen. Dramatically, for story purposes, I understood. But as a Black man who felt he was representing his community, it bothered me. There was a larger problem than maybe I could articulate at the time. But it stayed with me.

The Wire was real in the sense that those characters whose lives were in the street could be killed off at any time. That’s how it really is. Guys like Stringer Bell get killed. Guys like Omar Little get killed. The realism of that world demanded that Omar too meet his fate. So when the time came for him to go, I’d had enough preparation. But it was not easy.

Omar is killed unexpectedly, buying a pack of cigarettes, by a young kid in the streets. It’s not played for dramatic effect — there’s no slo-mo, no music. It’s even early in the episode; it’s just something that happens, just as it would really happen. The actor who played the shooter, Thuliso, was 10 or 11 at the time. We rehearsed it, but during the run-through we didn’t set off the squib, that small stick of dynamite on my clothes. The first time he saw the effect go off was when we were rolling; that scared look on his face you see onscreen is the real human being, the real little boy going into shock. He drops the gun and is freaked out; that’s not acting. We all stepped right into the real there.

After they yelled cut, he started crying, bugging out. “Is he all right? Is he all right? Michael?!” I had to console him. We had to wait awhile to make sure he was okay to finish the scene. Other setups were needed, and I had to lie there in that pool of blood. I’d died onscreen before — and I would again — but lying there, as Omar, was different. It felt like the end of something.

That day, when word got out that The Wire was shooting in the neighborhood, and that it was an Omar scene, the corners got packed. They had to cloak me behind a hood and robe so the onlookers couldn’t tell I had been shot in the head. That kind of information would get leaked; people would pay good money to know that. I’d actually get calls sometimes with people offering me money to tell them upcoming story lines so they could make bets about who was going to get killed on the show.

During a break that day, I went to the trailer and one of the wardrobe people, Donna, came in to change my shirt. She saw me sitting in front of my vanity mirror, headphones on, spacing out, listening to Tupac’s “Unconditional Love.” I was going into a dark place and she could see it all over my face. “Unh-uh, no,” she said, “we’re not doing this today, Michael. We are not doing this today. Snap out of it.”

I met her eyes and came back, but I couldn’t avoid it forever. It was strange energy on the set that day. People were trying to avoid having any feeling about the show coming to an end. People had come to like me and adore Omar, and there was this resistance, like no one wanted to allow themselves to feel. It was very businesslike: We got a job — no one’s got any time for that shit. Jobs begin and jobs end. That was a practical choice; we needed to get through it. But underneath all that, something heavy was lingering. Especially for me.

Omar’s death was also the death of something that had grown inside of me, something I’d grown inside of, merged into. That was a crippling realization. I remember thinking that if I wasn’t Omar anymore, then who was I? I had defined my worth through this fictional character, and now I was just Mike again. I felt stripped, lost, emptied-out. It was like this darkness crept in on me during the end of that show. In Philadelphia, Mayor Michael Nutter hosted a Wire finale screening party at city hall, with a huge projector, screen, and crowd. Afterward there was a panel for cast members and I sat up there in a pitch-back Boy Scout shirt, pulled my baseball cap low, and didn’t really speak. They’d ask me questions and I’d ignore them. I was too far inside myself to say a word. I didn’t even want to hear my own voice.

I might’ve looked like I was being difficult, but I was just afraid. It was like in Forrest Gump when he decides to stop running across the country and everyone following him just kind of stops too and wanders away. I felt like one of those people. Like, What do I do now? It wasn’t even about the next job. It was Where do I get this feeling again? How am I going to reach in and get that feeling? That drug, that Omar drug, that shit was powerful, and I didn’t have any legs to stand on. I didn’t know who I was because I had stopped doing work on myself. I was getting high and putting everything off. As I wrapped on The Wire, I knew I’d have to deal with the last four years of my life, having done whatever I wanted, damn the consequences.

Excerpted from the book SCENES FROM MY LIFE by Michael K. Williams with Jon Sternfeld. Copyright © 2022 by Freedome Productions, Inc. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.