I first became aware of Mike Myers through Saturday Night Live. I had been a huge fan of the show since the late ’70s, and suddenly this new kid emerged on “Wayne’s World” as Wayne Campbell, an Everyman from Aurora, Illinois, based on friends from Mike’s past — just a party-on kid who loves music and stages a show in his basement. And on “Sprockets,” in which he played Dieter, a Pop Art–loving, dance-crazed German talk-show host. One of my personal favorites was a hypoglycemic 6-year-old named Phillip. He’s this hilariously energetic kid who’s kept in a harness and says “I love you, you know.” On the surface, all of those characters were broadly comedic, but underneath they involved layers of intelligent design.

I met Mike in the early ’90s when he walked up to my wife, Susanna Hoffs, and me after a premiere to say he owned a signed Susanna Hoffs Rickenbacker guitar. After that, we started hanging out. On one occasion, he mentioned he was working on a project about an English spy frozen in the ’60s and thawed out in the ’90s. I offered to read the script, as a friend, and I quickly fell in love with Austin Powers. He was just as hilarious and specific as many of Mike’s SNL characters but even more so. He came with his own complete world. I wrote a lot of supportive notes along with some suggestions. He liked them — and then he asked me to direct it.

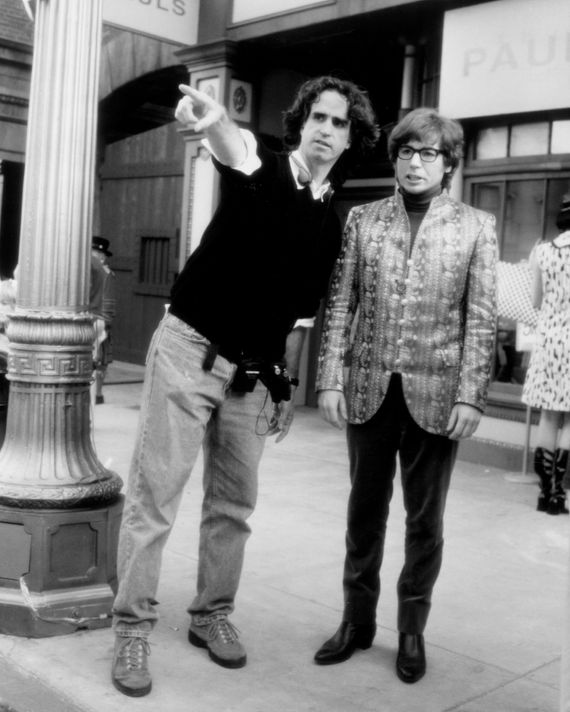

Directing Austin Powers was a life-changing event for me because I had no directing career and no hope of finding one. I’d worked on a few things as a screenwriter and on one feature, but it went horribly and I got fired before it was completed. Mike had this blind faith in me, and it didn’t seem rational; I really was not qualified to get that job. But we did have a shared vision, and Mike — along with the Todd Sisters, Suzanne and Jennifer, who were friends from USC film school and became producers of Austin Powers — had an instinct that I’d be a good collaborator. The head of the studio said, “We’re not going to just hire Mike’s buddy.” Mike said, “Don’t call me anymore until he’s the guy.”

Working with him was like going to comedy school. Mike has an encyclopedic sense of humor. He trained with Neil Mullarkey and other British comedians, and he’s very influenced by the English tradition. The James Bond–parody thing was, of course, a huge part of Austin. We were both crazy Monty Python fans and versed in Peter Sellers. Young Frankenstein was a big influence: It does a meta thing where it’s always commenting on its own pop-culture references, so there’s a kind of ironic distance. For people who were making such broad comedy, we talked a lot about Bertolt Brecht and how you can put the audience in a once-removed place, which is something Mike had been doing forever — for example, commenting on product placement in Wayne’s World. He’d always have a reference on the reference.

Mike’s characters are often disconnected from our reality and think more of themselves than is realistic. It’s a delusion that’s so funny to watch. If you have a character who’s deeply at odds with their own reality, you’re going to have predicaments. When Austin wakes up in the ’90s, he says, “As long as people are still having promiscuous sex with many anonymous partners without protection, while at the same time experimenting with mind-expanding drugs in a consequence-free environment, I’ll be sound as a pound.” Then you see Michael York and Elizabeth Hurley looking at him like, You poor soul, you’re gonna have a hard time here.

What Mike loves most are characters who straddle silliness and intelligence. Austin was fun — the bad teeth and the hair all over his body — but I always thought Mike’s deepest laughter came from the smart, specific humor of Dr. Evil. In the first movie, he’s in a therapy session and he starts to riff: When he was insolent as a child, he was placed in a burlap bag and beaten with reeds; he took luge lessons; his father claimed to have invented the question mark. Some of that run was written, but some was just Mike improvising. Because Dr. Evil looks so different from Mike, I feel like it gave him permission to lose himself more. It’s like he was possessed by that character.

An important part of the background of Austin is that it was widely rejected in Hollywood until Mike De Luca at New Line had the courage to pick it up. When we previewed it, it never scored well. But Mike Myers — similar to the characters he creates — has a certain amount of reality distortion. To some, he might seem delusional in his love for the material. That has been the case in everything he’s done since, too, from his mini-series The Pentaverate to The Gong Show. As with every comedian, some stuff is going to be explosive and some stuff may not be as explosive, but he’s so committed. Mike’s enjoyment of his own characters is letting himself get lost in them and hoping you’ll get lost in them too. Committing like that is the only way you can be really, truly funny.

He was very generous with the other actors as they brought their own energy to the characters. One of my favorite days of shooting Austin was when Carrie Fisher played the therapist. She was so nervous about it, and she didn’t know if she could be funny. She had recently become sober after a public struggle with addiction, an experience she mined in her novel and film, Postcards from the Edge. The hope was that her being super functional as the therapist would play against what people knew about her at the time. That’s Mike’s genius: to recombine her background with the world of the film and find a twist on it.

Mike’s love of his characters is always contagious. — but when we were making the first movie, it still took a lot of convincing to get people onboard with his vision. Mike would call the other actors and explain, and everybody loved him from SNL, so they trusted him and took the leap. By the time the second one came out, it was previewing through the roof and everyone wanted to be part of it. It speaks to his ability to create this sense of Let’s all jump in. It’ll take you places you never thought you could go. Some might think Austin was designed to be a fish out of water, but from Austin’s point of view (and Dr. Evil’s), he brought his own psychedelic water with him from the ’60s to the ’90s and got everybody else to swim in it. That’s what Mike Myers does, too.