Fox Rich is in her 20s when we first see her in Time, baby-faced and radiant despite the circumstances — despite her spouse, Rob, being in jail and having just come from jail herself. She’s 22 weeks pregnant with twins, and she can’t help but smile as she lifts her shirt to show her belly to a camcorder’s lens, just before Laurence, the youngest of the couple’s three sons at the time, pops up in front of her, his grinning face filling the frame. Cut to their second-oldest kid, Remington, on his way to his first day of school. Cut to Rich feeding the infant twins and then to a trip to an amusement park and then to one of the boys jumping into a pool, months and years slipping past in each edit. Cut to Rich talking to the camera as if it’s her husband, making it clear that these videos aren’t just a record of her life with their children but a way of contending with his absence. In 1999, Rob was sentenced to 60 years in prison for armed robbery — tantamount to life. These initial snippets are samples from an ongoing act of preservation on behalf of someone who couldn’t be there for all these moments both passing and pivotal. They’re also a document of a family that has had a hole cut out of its center.

Time is an extraordinary documentary from director and artist Garrett Bradley, who didn’t make a film about Rich and her family so much as make one with them. This collaboration can be felt most obviously in the years of home-movie footage that make up the opening and closing montages and are folded in throughout the 81-minute feature. But it also informs the very form of the work. In the time since her husband received his sentence and she served three and a half years for her part in the crime, Rich (full name Sibil Richardson) became an activist speaking on behalf of prison abolition while fighting for Rob’s release. The film periodically dips into a talk she gave at Tulane and then cuts to glimpses of similar ones in different locations over the years; it’s clear how her personal story has become a way in to making a structural argument about the harm done by incarceration. It doesn’t harm just the incarcerated individual but everyone in that person’s life: the loved ones who are separated from them, the children who grow up without them, and the community forced to move on. Rich’s family is her weapon and her rebuke, six sons we watch grow up into young men over the course of the movie, one of them going from kindergarten to dental school in the space of a heartbreaking edit — all that time they could have had together, gone.

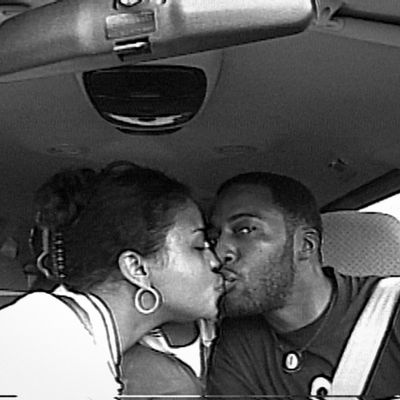

Bradley lets Rich’s perspective guide the shape of the film, making a case not from the specifics of botched legal proceedings or broader statistics but with intensely personal details — with the ever-accruing weight of love and loss. In the present, Rich owns a New Orleans car dealership and awaits a ruling from a judge that may finally send her husband home; she is both determined and honest about how every year has felt like the year and how remaining hopeful requires a degree of denial. Bradley’s footage is in black-and-white to meld with the lower-resolution home movies, and the camera nestles into the family’s life as if it were always there, capturing an interaction of such intimacy toward the end it’s a wonder that it doesn’t feel intrusive. It’s a testament to how deeply the director and her crew were embedded — or maybe it just speaks to how little the rest of the world matters to the two people onscreen in that stretch. Rich is intensely aware of the roles that perception and image play for her as a Black woman and the mother of Black boys, but the film captures both her outward presentation and her unguarded self. After days of patient, careful phone calls to the judge’s office, she allows a rare bit of anger to slip through after hanging up. “These people have no respect for other human beings’ lives,” she cries. “It will make you lose your absolute mind.”

Time is a counterbalance to the brutal bureaucracy of that system — insisting in its every frame on the unbowed humanity of its subjects in the face of systemic indifference. Bradley set her film to the music of Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, an Ethiopian nun known for her piano compositions. It’s a soundtrack that’s twinkling and wistful, and it feels as chronologically unmoored as the movie itself as it captures the terrible contradiction of how 20 years can feel both endless and as though it’s going by too fast, all at once. It sets up Bradley’s most poignant choice, to wind the clock back in the film’s final sequence, if only through the magic of cinema. Time marches inexorably forward, but the images we capture of the moment remain unchanged.

More Movie Reviews

- The Accountant 2 Can Not Be Taken Seriously

- Another Simple Favor Is So Fun, Until It Gets So Dumb

- Errol Morris Has Been Sucked Into the Gaping Maw of True Crime