It’s no shock that Sesame Street was born from a mixture of idealism and academic seriousness. Created by TV producer Joan Ganz Cooney and psychologist Lloyd Morrisett, then the vice-president of the Carnegie Foundation, the show aimed to bridge socioeconomic rifts and reach kids who were falling behind in their education before they had even started kindergarten. What does come as a bit of a surprise when watching the documentary Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street is the reminder that the legendary series was thought of as an attempt to harness the addictive powers of an inescapable mass medium for the forces of good.

In these days of screens and streaming, battles over the perceived disreputability of the boob tube feel as done with as the term boob tube itself, but in 1966, when Cooney and Morrisett first spoke about the subject at a dinner party, plenty of their peers considered television to be the domain of rotting brains and hawked products. In Street Gang, Cooney, who’s now 91 years old, says, “Every child in America was singing beer commercials,” as the jaunty strains of “When You Say Budweiser, You’ve Said It All” play over images of children looking at screens. Jim Henson, who died in 1990 and whose Muppets got their start in quirky ad spots as much as in late-night shows, drew a direct line between his advertising background and Sesame Street in a vintage clip. As he puts it, “I loved the idea of it; the whole idea of taking commercial techniques and applying them to a show for kids.”

Television hasn’t stopped selling us things, though the streaming era has added new complications to what’s being sold and how. Street Gang, a charming watch from director Marilyn Agrelo that’s based on the book by Michael Davis, is being released in part by HBO, which by 2016 effectively moved Sesame Street behind a paywall: It had made a deal with PBS, the show’s longtime home, which guaranteed the cable network (and, later, its streaming arm, HBO Max) a nine-month head start on first-run episodes. There’s no mention of this less inclusive development in the doc; Street Gang focuses on the heady early days of the show, which premiered on public–television stations on November 10, 1969, with the help of a hefty grant from the federal government. But running through the film is an awareness that while the creatives behind Sesame Street saw themselves as repurposing ad techniques for the public good, they were able to create the singular show only because they were liberated from commercial pressures. Sesame Street wouldn’t enjoy this freedom for the majority of its ongoing, decades-long existence, which gives the otherwise sweet Street Gang a touch of bitterness.

Agrelo steers clear of the straight-up hagiography that plagues so many docs framed as tributes to their subjects. While the film includes interviews with surviving members of the original Sesame Street crew—among them Cooney and Morrisett; cast members Emilio Delgado (Luis), Sonia Manzano (Maria), and Roscoe Orman (Gordon); and puppeteers Fran Brill and Caroll Spinney, who died in 2019—some of the other central creative voices are gone. The doc incorporates archival interviews from the likes of Henson, director and producer Jon Stone, and composer Joe Raposo as well as calling on their family members. The film has obvious reverence for Sesame Street’s freewheeling production and the dreamers and beatniks who came up with its characters and segments that shaped generations. This is tempered somewhat by reminiscences of these grown children who talk about the grueling workload required to put out the show, as well as the depression, the on-set tensions, and the way Sesame Street could feel like a rival sibling in their households.

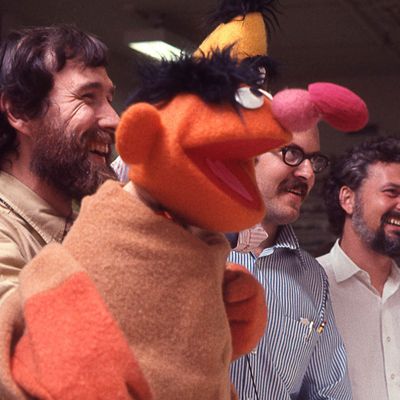

Most notably, Holly Robinson Peete, Matt Robinson Jr., and Dolores Robinson talk about Matt Robinson, who played the original Gordon and who created a Muppet named Roosevelt Franklin, who was intended to stand out and to be read as Black. As Dolores, his ex-wife, puts it, Robinson “wanted children of color to be recognized as children of color because in real life, those children knew they were different.” But Roosevelt Franklin drew complaints from Black viewers who saw him as perpetuating stereotypes, and he was dropped from the show—an incident that feels as if it could fuel a documentary in itself about how the unspoken utopian multiculturalism of the rest of the show has endured and aged. Street Gang isn’t that film. Instead, it offers a broader view of the formative years of this television landmark and its immediate resonance with viewers, including a wealth of behind-the-scenes footage that gives a peek into the secret lives of old, familiar friends. Seeing Henson and Frank Oz performing Bert and Ernie, or Spinney doing Oscar the Grouch while wearing the bottom half of his Big Bird costume, doesn’t ruin the magic. It enhances it.

Toward its end, Street Gang shows some of the one-on-one segments featuring a Muppet and a child about counting or learning directions or running through the alphabet. These were unrehearsed sequences that could work only because the human half of the pairing treated the puppet half as if it were real. And that was the thing about Kermit and Grover and Cookie Monster and so many of the show’s creations: They did feel real, right from the start, like complex, indelible personalities that happened to be made of felt. Street Gang is a document attesting to their lasting influence—and to why, even though it may seem to have plenty of competition now, a show like Sesame Street will never be made again.