This review was originally published on January 29, 2021. As of April 1, 2024, The Little Things is streaming on Netflix.

To those of us for whom the phrase “Denzel Washington crime drama” is a happy place unto itself, The Little Things can be rather frustrating. The film is about as old-fashioned as it gets: It was reportedly first written in 1993, and over the years has had a number of heavy-hitter auteurs attached to it, including Steven Spielberg and Clint Eastwood (the latter of whom had collaborated at the time with screenwriter, now director, John Lee Hancock on the elegiac manhunt masterpiece A Perfect World). It certainly feels like the kind of serial-killer thriller we might have had back when such movies meant big business: Tortured protagonist, fresh-faced partner, grisly killings, sudden twists, and heaps of atmosphere. It’s even set in 1990, either because nobody bothered to update the setting or — more likely — because the prevalence of things like cell phones would have undermined some of the film’s better set pieces.

So, why the heck doesn’t it work?

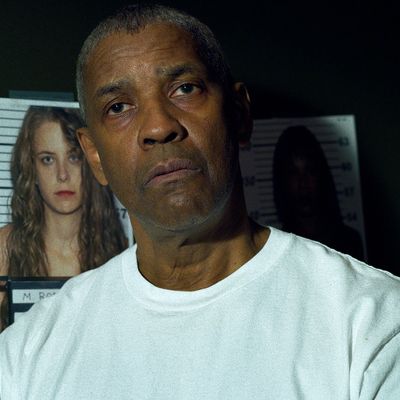

The Little Things starts off promisingly enough, with a tense, unnerving scene of a young woman being pursued by a mysterious driver at night on a highway near Bakersfield. We then cut to Joe Deacon (Washington), a lowly sheriff’s deputy in Kern County, California, as he returns to his old haunt of Los Angeles and unofficially joins the investigation into a rash of serial killings that bear some resemblance to murders that occurred when he was a homicide detective in L.A. Deacon is haunted, it seems, both by the women whose deaths he couldn’t solve — he talks to corpses and, at night, imagines the dead staring back at him — and by the unspecified cloud under which he left the department. His former partners and colleagues in the L.A. Sheriff’s Department view him with a combination of standoffishness and outright disdain.

But not Jim Baxter (Rami Malek), the young hotshot homicide detective in charge of the case, who is fascinated by Deacon and asks for his help in solving these crimes. For all his cocksure bravado, Baxter seems untainted by the cynicism and mordancy of the weary veterans around him. He still believes that as investigators they are working for the dead victims, and avoids his fellow cops’ chummy, banter-y gallows humor. Deacon doesn’t share Baxter’s earnestness, not any more, but he does share his clarity of purpose. (“Things probably changed a lot since you left.” “Still gotta catch ‘em, right?” “Yeah.” “Not that much has changed, then.”) He teaches Baxter to take note of the “little things,” the overlooked details of a crime scene or a perpetrator’s psychology that could give them clues as to who he might be.

On paper, it sounds great. As a genre piece, however, The Little Things is somewhat undermined by its inability — or perhaps unwillingness — to clarify the parameters of the case, to establish who or what our heroes are looking for. That’s not a fatal flaw, and it could have been an asset: The film seems more interested in the psychological toll of police work, of the debilitating drudgery of failure; it wants to be more character study than procedural. But it half-asses that, alas. The script plays coy with the skeletons in Deacon’s closet, waiting until the end to reveal their exact nature, which is a cheat because almost every other character knows what those skeletons are. (Baxter doesn’t, but the film isn’t from Baxter’s point of view — it’s mostly from Deacon’s.)

This screenwriter’s ploy winds up damaging the performances. Because we don’t know the real source of Deacon’s torment, his brooding comes off as vague and generic, and there’s little Washington can do with the part other than, well, look tormented. Malek, meanwhile, never seems comfortable in the role of the idealistic detective; it feels like he’s playing an idea, rather than a person. Furthermore, beyond the initial setup of their relationship, the interactions between Deacon and Baxter don’t really develop in any meaningful way, save for a sudden turn right at the end. Maybe in the hands of a director with a better control of mood, a firmer focus on characters, and a sharper understanding of how to play with pulp iconography — say, Eastwood, and in particular ’90s Eastwood — it might have worked.

But then Jared Leto shows up, and things get interesting again. As a suspect, his character makes an impression at our first, brief glimpse of him — perhaps because he’s being played by an Oscar-winning actor, which suggests this random, unnamed dude will turn out to be a major player. Leto brings just the right mixture of creepy disdain to his part. Without getting too far into spoiler territory, let’s just say that he introduces a welcome element of unpredictability into what has felt up until then like a derivative and not at all distinctive thriller. (I realize I am saying here that Jared Leto is the high point of a film that stars Denzel Washington and Rami Malek, and, no, I haven’t yet made my peace with that.)

The Little Things, however, is distinctive in certain ways. It ultimately goes in a fairly surprising direction, which perhaps justifies some of its more familiar genre moves earlier. But it doesn’t entirely earn its twists, in part because it botches both the whodunit elements and the psychology of its characters. In most cop thrillers — even in such masterful outliers like Se7en and Silence of the Lambs — the protagonist’s demons take a back seat to the typical ins and outs of the central narrative. That’s true in The Little Things as well, but by the end, when the demons are revealed to be far more central to the plot than previously imagined, the film’s moves begin to feel like a cheat. It wants to eat its genre cake and have it too.

More Movie Reviews

- The Accountant 2 Can Not Be Taken Seriously

- Another Simple Favor Is So Fun, Until It Gets So Dumb

- Errol Morris Has Been Sucked Into the Gaping Maw of True Crime