The story of Mohamedou Ould Salahi was among the most disturbing to come out of the Guantánamo Bay prison camp over the past couple of decades. Detained on dubious grounds, held without charge, brutalized and tortured and forced into a false confession, Salahi spent 14 years at Gitmo — some of those years coming after he won his case against the U.S.

government and secured release. You can use any number of eponymous adjectives for it — Kafkaesque, Orwellian, sadistic, Stalinist — and still not do justice to the monstrousness of what was done to him. Directed by Kevin Macdonald and based on Salahi’s own 2015 memoir, Guantánamo Diary, The Mauritanian is a noble but staid effort at trying to tell this man’s tale. Its beats are familiar, its outrage muted, its story diffuse. But then, in its final moments, it springs one brilliant, devastating sucker punch that’s so hard to shake it nearly saves the mostly humdrum movie that preceded it.

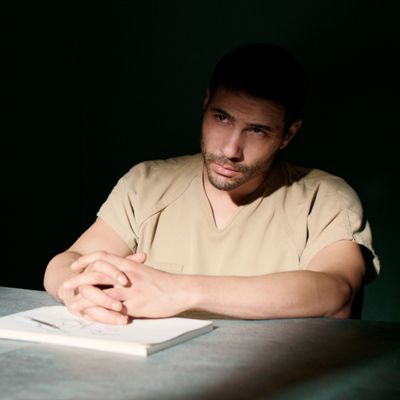

The Mauritanian starts with the capture of Salahi (Tahar Rahim) at a wedding back in his home country (he has just returned, we’re told, from Germany), then quickly fast-forwards to the development of his court case. We see Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster), a veteran defense attorney, agreeing to take up the case, with what appears to be some reluctance, and traveling to Gitmo alongside her associate Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley). On the other side is military prosecutor Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch), a former pilot whose closest friend had been on the plane that struck the World Trade Center’s South Tower, making this a personal matter for him. It’s easy to see how a film like this might have been made 20 or so years ago: It would have focused on the lawyers and the legal machinations around Salahi’s case, with little time spent on the man at the heart of it all. And to be fair, that might have been a more exciting, more conventionally satisfying political-legal thriller. By grounding itself in Salahi’s experience — in his years spent at Guantánamo, his memories, his solitude, his growing despair, and his changing relationship with the world around him — The Mauritanian forsakes suspense for humanism, which is not a bad trade-off.

The problem is that it still tries to muscle a legal drama in there. Whenever we pull away from Salahi, the narrative becomes disjointed and confusing, even as the performances keep things going. Foster, who’s been away from our screens for some years, is a welcome sight, layering her crusading character with moments of doubt and hesitant acquiescence. Hollander’s patience for the byzantine nature of this particular case (which is wrapped up in all sorts of military law and procedure) is clearly at odds with her idealism, but to the film’s credit, this dilemma is treated in subdued fashion, almost as a grace note. Cumberbatch’s character — a deeply religious, earnest hard-ass who begins to have his own doubts — might actually be more interesting, with a more pronounced character arc, but he seems to get less screen time and feels the least developed among the major characters. (This might also be because Cumberbatch, for all his talent, isn’t quite as subtle an actor as Foster is.)

On a narrative level, the legal minutiae The Mauritanian presents is handled in such a cursory fashion that you might find yourself lost at times. (I know I did, and I sat through the film three times.) It’s on firmer ground when it cuts to Salahi — and Rahim is certainly excellent — but even there, Macdonald attempts too much; a couple of dream sequences, which are presumably meant to illustrate both Salahi’s trauma and the mental disorientation caused by constant torture, humiliation, and accusation, actually come off as vaguely ridiculous, pulling us out of the picture. Salahi’s backstory is also disjointed: There’s an interesting tale there in his joining Al Qaeda back when the group was something of a U.S. ally, in his life spent in both Western and Islamic societies, in the odd circumstances under which he was mistaken for a notorious terrorist recruiter. But in consigning that tale to half-remembered glimpses, the film loses much of the emotional and narrative thread.

But again, the movie rallies mightily by the end. I won’t reveal how it ends (though those familiar with Salahi’s case might be able to guess), but Macdonald and his writers, after presenting us with a film that, for all its narrative ambitions, represents a fairly middle-of-the-road effort stylistically, unleash one quick, formal gambit that’s not only striking but actually speaks to the broader tragedy of America’s forever wars and their associated absurdities. The film denies us closure, because, let’s face it, none of this is really over yet.

More Movie Reviews

- The Accountant 2 Can Not Be Taken Seriously

- Another Simple Favor Is So Fun, Until It Gets So Dumb

- Errol Morris Has Been Sucked Into the Gaping Maw of True Crime