On January 23, 2024, Napoleon was nominated for three Oscars. Be sure to read our review.

Napoleon Bonaparte became the ruler of France at age 30, conquered most of Europe before he was 40, and died in exile at 51. It’s the sort of life that seems like it would make a pretty good movie — yet every modern attempt has either stunk (1954’s Désirée, 1970’s Waterloo) or fallen apart before cameras rolled (Stanley Kubrick’s unmade biopic). That makes Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, a $200 million, 157-minute epic starring Joaquin Phoenix, by default the definitive film about the French emperor.

The director of Gladiator and Black Hawk Down has restaged so many historical battles in his five-decade career that he’s practically a general himself. “We shot this entire film in 62 days,” Scott says on a call from his winery in Provence with his dog, Josephine, on his lap. “If you know anything about filming, you’d know it should’ve been 120.” He did it using Napoleonic powers of delegation. “I have 40 department heads who all have their own pyramids of personnel, so the unit is almost 900 people,” he says. “Every Monday morning, I’d say, ‘Right — anybody got a problem? What’s your problem? Have you talked to so-and-so? No? Well, bloody talk to them!’”

The movie’s most complex sequence is a re-creation of the Battle of Austerlitz, which is usually considered Napoleon’s masterpiece. On December 2, 1805, the French army lured Russian forces onto a frozen lake and fired cannons at the ice as they retreated. Legend has it that many of those soldiers drowned — we see a few take the plunge in Napoleon — though historians often point out that when the lake was drained, only a couple of bodies were recovered. “Everybody has an opinion about what really happened, and I always ask, ‘Were you there?’” says Scott. “There are 10,000 books about Napoleon, and they’re full of both truth and conjecture. But I left reading the books to the poor bastard who had to write the screenplay.” This is how Scott and his army refought Austerlitz.

1.

Readying for Battle

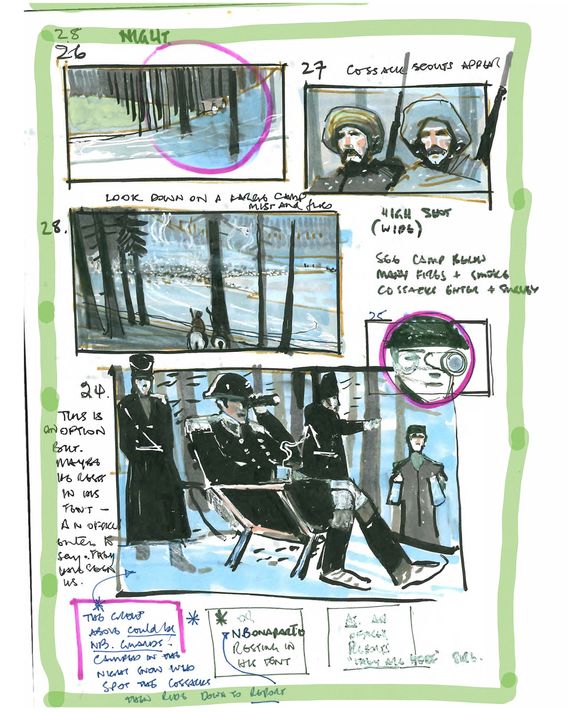

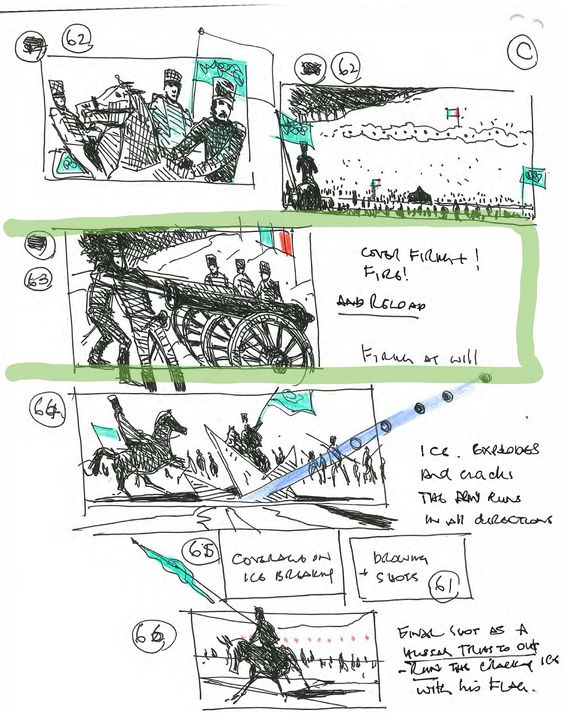

Scott’s process begins with storyboards, which he draws by hand. For Napoleon, screenwriter David Scarpa would email him pages of the script and Scott would send back illustrations of each shot, usually within a day. “I’m still a painter,” says Scott, who once studied at London’s Royal College of Art. “I edged into directing through design and only gradually learned to talk to actors, which took a while.” Scott’s finished films tend to look uncannily like his original drawings. “They’re pretty identical,” he says. “Sometimes if I don’t have a location for a scene, I’ll draw it and my scouts will look and say, ‘Oh, okay’ — and then they’ll go find the location. It’s weird.”

In Napoleon, what passes for Austerlitz is actually a digital composite of two locations. The wooded hill that serves as Napoleon’s command post is a site in Bourne Woods near Surrey, England, where Scott previously filmed 2000’s Gladiator. The frozen lake where most of the fighting takes place isn’t a lake at all. “That was actually Abingdon Airfield, just off the M4 motorway out of London,” says Scott. “The last thing you’d want to do is go on an actual lake and do the shit that we did. That’s how you get in real trouble.”

2.

Taking Aim

According to Scott, the Battle of Austerlitz shoot was scheduled to last six days, “but we did it in three and a half.” One secret to the director’s efficiency is that he shoots with multiple cameras simultaneously — for Napoleon, usually four but sometimes as many as 11 — requiring fewer takes and less time between them to reset. “In the morning, I’ll tell my brilliant cinematographer, Dariusz Wolski, ‘I want a camera there and there and there and there. How long to set them up?’ He’ll say, ‘40 minutes,’ and I’m shooting by 9 a.m.,” Scott says. “Other directors use one camera and they go on forever, but this literally allows me to shoot 4-to-11 times faster.”

During production, Scott’s command post is a custom trailer where he watches his camera feeds on an array of large monitors. “It’s a converted horse box. It’s my zone. I don’t like anybody else in there with me,” he says. “I’ll sit there in the dark with a walkie-talkie and say, ‘Hey, Joe on camera one, you’re a bit wide. Can you tighten? Pete on camera two, change your lens.’”

The Battle of Austerlitz involved upwards of 68,000 French troops and 90,000 Austro-Russians. But in Hollywood, there are logistical limits to how many live extras can share a scene. “You can’t really do more than 600 foot soldiers in a day,” says Scott. “They have to come in at 4 a.m. to be ready by nine, and that’s with 200 people working as dressers.” For Napoleon’s battles, 400 human soldiers and 100 horses were positioned on the front lines, and CGI was used to expand their ranks behind them. “The extras were great,” says Scott. “God bless them, because I wouldn’t want to sit there with a cup of tea waiting all day to walk past something.”

3.

Firing Away

Napoleon’s favorite pieces of artillery were his cannons — he called them his belles filles, or “beautiful daughters” — and you can tell Scott liked them too. In an early scene that sets the tone for the rest of the film, a horse is blown to pieces by a cannonball, which Phoenix’s Napoleon recovers as a souvenir. But no live cannonballs were discharged while filming; Scott’s cannons were props that fired blanks. They were made of carbon fiber instead of steel, and their insides were solid so that when charges were placed on their muzzles, the blasts would point outward. In the film, Phoenix makes a show of covering his ears whenever cannons are fired. “They were loud on the set, but we made them sound huge during the sound mix,” says Scott.

At the climax of the Austerlitz sequence, Napoleon gives a dramatic hand signal ordering French gunners to fire cannons at the frozen lake, which sends his retreating enemies into the water below. We see one soldier on horseback attempt to outrun the cracking ice, and several others sink to the lake’s bottom. For shots of troops and horses falling through the ice, the production dug a 30-by-40-meter hole in the ground on location at the airfield. The underwater shots were filmed in a tank on a soundstage at nearby Pinewood Studios. “For their safety, you can only put two horses in the tank at a time,” says Scott. “But we put the men falling in there as well, so they were trying to avoid the horses and getting clobbered by their hooves. They were all stunt guys. It was absolutely baffling to me, but they loved it.”

Although roughly 150 horses are thought to have died at the actual Battle of Austerlitz, none were harmed on set. “I love animals, so I protect them like crazy,” says Scott. “Any horse you see flying through the air in this film is a dummy.”

4.

La Victoire

At Austerlitz, Phoenix’s Napoleon is at his most confident and focused, executing his plans with careful precision. “He put 4,000 of his men at the edge of the lake with tents and fires and music and deliberately made them sitting ducks to bait the Russians and Austrians,” says Scott. “That’s when command tells him, ‘Your Majesty, we have been discovered,’ and he says, ‘Good.’”

Off the battlefield, Phoenix sometimes plays the character as sort of a goofball. In one scene, Napoleon’s men tell him it’s too cold to invade Russia during the winter; Phoenix responds with an unscripted tantrum, fumbling his hat. “That was all Joaquin’s idea,” says Scott. “I said, ‘What the fuck was that? Anyway, that was good. Cut.’” The Coup of 18 Brumaire — in which Napoleon seized power from the French Directory in 1799 — becomes an extended feat of physical comedy as Phoenix is chased, wheezing and eyes bulging, from the royal palace. “That was one take, shot with eight cameras,” says Scott. “He gets beaten up like in a rugby scrum, and he runs away and falls down the stairs. I thought he’d broken his fucking leg. I called cut and said, ‘You want to go again?’ And he said, ‘No, no. I hurt my hip.’”

Scott originally had someone else in mind to play Napoleon. “There are only two actors today that I think would’ve been good for the role — and I’m not going to say who the other one is because he’d get pissed off,” says Scott. “But Joaquin Phoenix really looks like Bonaparte. He has the nose and the eyes. Before I cast him, I took a photograph of him and stuck a hat on it, and I said, ‘There it is.’”

More on ‘Napoleon’

- The 50 Greatest War Movies Ever Made

- Every Ridley Scott Movie, Ranked

- Presenting the First Annual ‘Bunch of Boys’ Awards