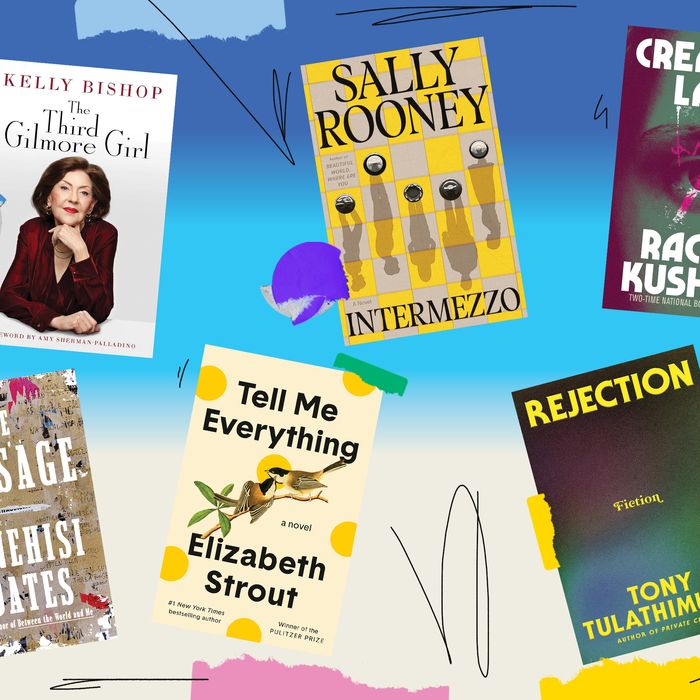

There are many words associated with autumn, but few speak to the season quite like “crisp” — the crunchy leaves, the apple treat, the cool breeze, and the pages of a fresh book. Even for those who are long past their days of compulsory education, the call to end summer with a trip to the bookstore or library to grab a full backpack’s worth of hardbacks might just feel mandatory. Luckily, there’s nothing stale about our recommended-reading list. This fall, we’re staying up late with ghost stories from an Argentine master of horror; we’re following a New Yorker writer on a wild trip through Brooklyn’s underground dance scene; and we’re taking a hard look at America’s many, many problems through fiction and nonfiction alike (how apt for an election year). Pour yourself a warming beverage, find a spot on a comfy chair, and settle in for a read that’s as refreshing as the season.

September

Greenwell’s latest novel begins during lockdown. In the What Belongs to You author’s characteristic style — winding sentences that feel urgent and philosophical — a narrator guides us through his trip to the ICU for a serious heart condition. He’s on his domestic partner’s insurance; the visit would’ve been cheaper were they married. Through asides like these, the author considers death, pain, love, and American health care with an interest in the power dynamics at play in intimate spaces. —Maddie Crum

Sadie Smith, a former U.S. spy, is a ruthless observer of human behavior with total faith in her ability to manipulate it. She makes her way to rural France, where she’s been hired to infiltrate an anarchist commune and stir up trouble. Meanwhile, a radical from an earlier generation is living in a network of caves — a life that Sadie is increasingly drawn to. Kushner, the author of The Flamethrowers and The Mars Room, is as intimidatingly intelligent as this twisty novel’s main character. —Emma Alpern

Since her best-selling debut, 1998’s Caucasia, Senna has explored biracial identity through a series of acerbic novels and stories. Here, a writer named Jane is struggling to finish her book, a sweeping treatise on the mulatto experience. Meanwhile, her old grad-school buddy, a successful TV showrunner, leads a project abroad while Jane and her family house-sit for him in L.A. When Jane connects with another vaunted showrunner, she’s sucked into a strange, demanding relationship. This novel questions the utility of literature in a pop-culture-addled world. —Tomi Obaro

Following her Vernon Subutex trilogy, Despentes’s latest opens with an Instagram post: Oscar, an author from a working-class background, insults Rebecca, an aging actress, over her looks, prompting the angry star to contact him. Their ensuing correspondence turns from begrudging to engaged. When Oscar’s former publicist publicly accuses him of sexual harassment, they’re both forced to confront their feelings about the Me Too movement. This epistolary novel is a bitingly humorous conversation about addiction, lockdown, cancellation, and, ultimately, friendship.

—Jasmine Vojdani

In this cross-book collaboration that will delight Strout fans, Olive Kitteridge, the crotchety widow played by Frances McDormand in the HBO adaptation of Strout’s Pulitzer-winning novel, lives in a retirement home on the outskirts of a fictional Maine town. She invites writer

Lucy Barton to listen to her stories. Lucy has also become close friends with Bob Burgess, a lawyer and main character in The Burgess Boys, who is defending a man accused of killing his own mother. Strout covers the ghosts of marriages and the indignity of old age with her usual thoughtfulness. —T.O.

Class has always been the engine of Alam’s fiction (Leave the World Behind features some excellent food porn). Here, Brooke, a Black 30-something former public-school teacher, joins a mysterious philanthropic organization run by a white billionaire. As he invites her into his inner circle, she becomes entranced by the trappings of extreme wealth. —T.O.

Pedro Almodóvar describes his new story collection, The Last Dream, as a “fragmentary autobiography, incomplete and a little cryptic.” The book is a genre-agnostic spin through the Spanish filmmaker’s favorite preoccupations: doleful divas, Catholic education, rebellion, and the countercultural ferment of Madrid after Franco’s rule. “The Life and Death of Miguel,” a bildungsroman, is a highlight, written when Almodóvar was around 18, “on an Olivetti typewriter under a grapevine with a skinned rabbit hanging from a string.” Another notable entry, “Too Many Gender Swaps,” is about the breakdown of a relationship filtered through some of Almodóvar’s biggest artistic influences: Tennessee Williams and John Cassavetes. —Brandon Sanchez

You know what’s really gratifying about this book? It doesn’t dwell too long in childhood. Bishop’s memoir dives right into her love-hate relationship with Michael Bennett, the Broadway legend who created a Tony-winning role for her in A Chorus Line. Then she gets into her Vegas-showgirl stint, Dirty Dancing, and Gilmore Girls. Bishop’s discussions of her abortion, her great love (husband Lee Leonard), and her other great love (Gilmore Girls creator Amy Sherman-Palladino) propel the book forward.

—Bethy Squires

In a new collection of short stories, this Argentine horror master’s tales of the drudgery and sorrow of modern life are interrupted by the cruel and strange whims of the supernatural. The characters are haunted—by goblins, curses, and ghosts of various temperaments (angry, scared, horny)—but also by a sense of loss. There’s beauty in the macabre fates that await these tormented souls. —Tolly Wright

Tulathimutte’s unnerving depiction of angry losers in these interconnected stories is hard to look away from. “The Feminist” inspects the life of a man who goes out of his way to signal allyship to his collection of female friends and fails to convert those relationships into something more. In “Pics,” a woman’s bitter obsession with a man she slept with once alienates even the enablers in her group chat. The book eventually turns on itself in a chapter written like a rejection letter from an unmoved publisher. —E.A.

In her 2016 nonfiction book, Future Sex, the journalist sought out her own authentic sexuality. In this follow-up, Witt’s new realm of self-experimentation is drugs of all kinds and the Bushwick rave scene from 2016 to 2020. She recounts working on the road as a New Yorker reporter, witnessing the trauma of school shootings and far-right rallies, rushing to file, then going home to cleanse herself in the healing hedonism of the all-night party. As the love affair that introduced Witt to the scene unravels and COVID reaches the city, the freedoms found on the dance floor feel lost forever. —Emily Gould

Powers’s last book, Bewilderment, was a smaller-scale look at the relationship between a widowed astrobiologist and his sensitive son. Playground returns to the sprawl of The Overstory, telling the interlocking tales of four people brought together by chance to build autonomous cities in the ocean. Set in the near future, it deals with Powers’s usual concerns about the environment, and it’s already on the Booker longlist. —T.O.

After Beautiful World, Where Are You, a novel of emails between two best girlfriends, Rooney focuses on brothers Peter and Ivan, who have just lost their father. While Ivan, a pro chess player, strikes up a romance with an older woman, Peter, a lawyer, shuffles between a younger sex worker and an ex-girlfriend whose life was forever changed by a car accident. Rooney mints a stream of consciousness that plunges us deeper than ever into the minds of her characters — and the complex dynamics that alternatively rend them apart and bring them together. —J.V.

.

Other books coming in September

The Life Impossible, by Matt Haig (September 3)

Horror for Weenies, by Emily Hughes (September 3)

Where They Last Saw Her, by Marcie R. Rendon (September 3)

The Essential Elizabeth Stone, by Jennifer Banash (September 10)

Two-Step Devil, by Jamie Quatro (September 10)

Big Fan, by Alexandra Romanoff (September 10)

Bone of the Bone, by Sarah Smarsh (September 10)

Want: Sexual Fantasies by Anonymous, by Gillian Anderson (September 17)

Something Lost, Something Gained, by Hillary Clinton (September 17)

The Empusium, by Olga Tokarczuk (September 24)

-

Adam Pearson Is No Wallflower

Adam Pearson Is No Wallflower -

Nicole Scherzinger Never Stopped Dreaming

Nicole Scherzinger Never Stopped Dreaming -

Charli XCX Is Too Brat to Fail

Charli XCX Is Too Brat to Fail -

Jamie xx Didn’t Ruin Club Music

Jamie xx Didn’t Ruin Club Music -

Josh Rivera Takes the Lead in American Sports Story

Josh Rivera Takes the Lead in American Sports Story -

10 Anime We Can’t Wait to Watch This Fall

10 Anime We Can’t Wait to Watch This Fall -

30 Classical-Music Performances to Hear This Fall

30 Classical-Music Performances to Hear This Fall -

Here Are All the Fall Openings We’re Watching

Here Are All the Fall Openings We’re Watching -

Kaytranada Owns His Influence

Kaytranada Owns His Influence -

Garth Greenwell’s Grand Romance

Garth Greenwell’s Grand Romance

-

Adam Pearson Is No Wallflower

Adam Pearson Is No Wallflower -

Nicole Scherzinger Never Stopped Dreaming

Nicole Scherzinger Never Stopped Dreaming -

Charli XCX Is Too Brat to Fail

Charli XCX Is Too Brat to Fail -

Jamie xx Didn’t Ruin Club Music

Jamie xx Didn’t Ruin Club Music -

Josh Rivera Takes the Lead in American Sports Story

Josh Rivera Takes the Lead in American Sports Story -

10 Anime We Can’t Wait to Watch This Fall

10 Anime We Can’t Wait to Watch This Fall -

30 Classical-Music Performances to Hear This Fall

30 Classical-Music Performances to Hear This Fall -

Here Are All the Fall Openings We’re Watching

Here Are All the Fall Openings We’re Watching -

Kaytranada Owns His Influence

Kaytranada Owns His Influence -

Garth Greenwell’s Grand Romance

Garth Greenwell’s Grand Romance

October

The essay collection’s first half treads familiar territory: In one, Coates travels to Dakar for the first time and considers his lost African heritage; in another, he follows the story of an English teacher in danger of losing her job for teaching Between the World and Me. But the longest and arguably most contentious part reckons with the Zionist project and his own previous writing, most memorably a 2014 article that treated German compensation to Israel as a form of reparations and didn’t address Israel’s occupation of Palestine. —T.O.

In the Pulitzer-winning Ojibwe and German American author’s latest novel set in North Dakota, Crystal, who works the night shift hauling sugar beets, tolerates the rebelliousness of her teenage daughter, Kismet, but finds it hard to ignore what she believes to be bad omens. Kismet is caught in a love triangle, and the relationship she chooses threatens to break her. The novel is populated with Erdrichian characters — like a priest called Father Flirty whose hair recedes “in a perfect zigzag, like a vampire’s” — keenly aware of the forces that threaten the land they live on. —E.A.

Ina Garten took a winding path to becoming one of the biggest stars in food television. She left a White House job managing nuclear-energy budgets to run a gourmet food store in the Hamptons, wrote a hit cookbook, and, in her 50s, began her Food Network show, Barefoot Contessa. In the process, she endeared herself to home cooks, making the classiest recipes seem effortless. Her debut memoir trades her usual cooking advice for life advice (all while gushing about her husband, Jeffrey). —Justin Curto

Booker Prize winner Hollinghurst is back in familiar territory (thank God!) with his sixth novel, set partly in the present day and partly during the boarding-school beginnings of his sensitive, preternaturally observant protagonist David Win. Half Burmese and lower class, Win faces discrimination at every turn in his posh school, most notably at the hands of a vile bully named Giles, the son of a genteel family who have provided David’s scholarship. David grows up to be a talented actor, while Giles becomes a powerful conservative politician. Hollinghurst doesn’t hesitate to linger over scenes of exquisite sensory detail and complex social ritual — the lift of a brow, the inflection of a voice. This lends the book a richness and subtlety that sets it apart from most contemporary fiction. —E.G.

At just 19 years old, lyricist and poet Robert Hunter spent his days languishing around “the scene” — that psychedelic bridge between the beatnik artists of the late ’50s and the counterculture revolution of the ’60s. For Hunter, “the scene” was hanging around Palo Alto’s coffeeshops nursing one unlimited cup of coffee, it was bookstores and parties, and long walks nowhere with Jerry Garcia. In the unearthed manuscript from Hunter, who was the Grateful Dead’s primary lyricist and the only non-performing band member to ever be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, both casual fans and Deadheads alike will find something to get lost in. With cameos from Jerry (Garcia), Barbara (now Brigid Meier), The Silver Snarling Trumpet features profound poetry, trippy visions, and playful anecdotes about one of the most influential bands ever. —Morgan Baila

“By chance I have reached a positive conclusion; it’s time for me to stop.” So ends the acknowledgments of what is believed to be the beloved but controversial French author’s final book. The novel, set in the lead-up to the 2027 presidential election in an imperiled France, features Paul Raison, an adviser to the finance minister who leaves Paris to care for his ailing father in the provinces. Houellebecq’s supposed swan song wrestles with the questions of how to love and how to disappear. —J.V.

Long heralded as one of literature’s preeminent voices, John Edgar Wideman has faithfully chronicled the experiences of African Americans for almost 60 years. His work is singular; it defies categorization while inviting readers to engage with familiar ideas in startlingly new ways. His latest blends memoir, fiction, and history to describe what he calls the “slaveroad,” a psychological and geographical artery that extends from Africa to the Global North; from the 16th century to the present day; and from his own family’s travails to a wider consideration of the African American experience. This book offers a fresh perspective of slavery’s impact and a confirmation of Wideman’s exalted status in American letters. —Tope Folarin

C.J. Leede’s debut, Maeve Fly, established her extreme horror credentials — there is a scene with a curling iron that will turn even jaded readers’ toes. In American Rapture she’s gone bigger, bolder and perhaps even more upsetting. A COVID-like illness sweeps the nation, carried on an ill wind. The lucky die from the flu; others devolve into disinhibited, sexually voracious almost-zombies. It’s a nightmarish premise, more frightening still seen through the eyes of Sophie, an inexperienced teenager. Sophie’s attempt to navigate this gruesomely lustful reality has all the hallmarks of great apocalyptic fiction. But beneath some fantastic set pieces and truly soul-scarring events, there is a furious satire of America’s sexual politics. —Neil McRobert

Fans of dearly departed website the Toast will long be familiar with Daniel Lavery’s penchant for humorous turns of phrase and his distinctly literary imagination. In his debut novel, Lavery turns that sensibility to the brief phenomenon of women’s hotels: residences for single women living alone in big cities, which he describes in an author’s note as “somewhere that was socially and professionally accepted by everyone, and yet was decidedly, categorically, not a home.” There are myriad reasons a young woman might seek such an arrangement — some obvious and some less so — and Lavery explores plenty of those reasons through a cast of delightfully offbeat misfits living at the fictional Biedermeier (basically the Barbizon we have at home) in the 1960s. —Emily Heller

The author of the genuinely spine-tinglingly spooky Ghost Wall and several other novels, turns the lens on herself in this fragmented and poetic memoir that mines her childhood for the roots of her eating disorder, and engages with the books that shaped her as she grew to become a novelist. Moss’s parents were woefully indifferent to their sometimes difficult daughter, but this memoir treats them fairly by dabbling in everyone’s point of view, going back and forth between authoritative narration and questions and contradictions in italics. The result can sometimes be a frustrating lack of cohesion, but at dramatic moments the approach reveals something that seems to approach truth, in all its messy, kaleidoscopic glory. —E.G.

The Southern Reach trilogy is one of few 21st-century science-fiction stories to attain true classic status. To everyone’s surprise, a decade after 2014’s Acceptance, VanderMeer is taking us back to the enigmatic Area X in pursuit of closure. This follow-up promises to tell us more about the origins of the anomaly and its earliest, forgotten expeditions and explores the consequences of discoveries made in the first three books. —N.M.

.

Other Books Coming in October

The Third Realm, by Karl Ove Knausgaard (October 1)

Shred Sisters, by Betsy Lerner (October 1)

A Song to Drown Rivers, by Ann Liang (October 1)

A Thousand Threads, by Neneh Cherry (October 8)

Paper of Wreckage, by Susan Mulcahy and Frank DiGiacomo (October 8)

From Here to the Great Unknown, by Lisa Marie Presley and Riley Keough (October 8)

This Cursed House, by Del Sandeen (October 8)

Sonny Boy, by Al Pacino (October 15)

Dogs and Monsters, by Mark Haddon (October 15)

Memorials, by Richard Chizmar (October 22)

Every Valley, by Charles King (October 29)

The Blue Hour, by Paula Hawkins (October 29)

November

Lili Anolik has appointed herself the guardian of Eve Babitz — her literary reputation, her romantic legend, and her Los Angeles. Her previous book, Hollywood’s Eve, dished on the good and bad in Babitz’s life. Here, she frames Joan Didion and Babitz as opposites, a snob/slob, Apollo/Dionysus, Daria/Quinn dyad. Her double biography is an account of a dispute between highly creative frenemies where the wounds festered for years and no one ever worked it out on the remix. —B.S.

People continue to get Cher wrong — scoffing at her rock-star bonafides, undervaluing her impact on pop music, writing her off as a has-been. There’s a reason she didn’t get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame until this year. So let’s let the woman herself tell her story this time, in a long-awaited two-volume memoir. The first part promises a look at Cher before she became a household name, from her turbulent childhood through the highs and lows of her partnership with Sonny Bono. —J.C.

A lonely hero; a Beatles fan; a hidden, off-kilter world; a missing lover. Murakami’s first novel in six years has enough of his trademarks to fill a bingo card. The novel grew from a short story of the same name published in 1980. Readers who appreciate the acclaimed author’s absurd humor won’t find as much of that here, but you don’t have to be a completist to enjoy his metafictional constructions or his subtle whimsy. —M.C.

.

Also Coming in November

The Name of This Band Is R.E.M, by Peter Ames Carlin (November 5)

I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying, Youngmi Mayer (November 12)

Lazarus Man, by Richard Price (November 12)

The Collaborators, by Michael Idov (November 19)

City of Night Birds, by Juhea Kim (November 26)

More From Fall Preview

- Adam Pearson Is No Wallflower

- Nicole Scherzinger Never Stopped Dreaming

- Charli XCX Is Too Brat to Fail