This post was originally published on July 27, 2022, to mark Norman Lear’s 100th birthday. We are republishing it after the news of Lear’s death, alongside Kathryn VanArendonk’s obituary for the TV legend.

Television as we know it could not exist without Norman Lear. Throughout his 70-plus years in the business, the writer and producer brought topics like racism, abortion, divorce, drug use, and poverty to prime time. Zeitgeist-defining shows including All in the Family, The Jeffersons, One Day at a Time, Maude, and Good Times aimed to entertain and educate while countering the growing right-wing Christian influence on showbiz in the ’70s and ’80s. Today, Lear remains as prolific as ever, producing original series and films, rebooting his greatest hits, underwriting documentaries, and occasionally acting.

July 27, 2022, marks Lear’s 100th birthday. To celebrate this milestone, 19 of his friends and collaborators — including actors, writers, producers, and executives — shared their favorite stories of his endless imagination and curiosity, willingness to break boundaries, sense of fairness and patriotism, and, of course, mischievous sense of humor.

Norman the Career-Maker

“It’s like a fairy tale”

I was performing stand-up at the second annual Media Access Awards in 1980, and Norman and Charlotte Rae were in the audience. I got a standing ovation for my routine. I was brought to meet Norman, and he said, “You’re a really funny kid, but you’re way before your time.” I said, “So wait a couple of months.” Two and a half months later, he cast me in Facts of Life. It’s like a fairy tale.

In 1982, he hired me to do a special called I Love Liberty. It was a huge show with Christopher Reeve, Barbra Streisand, Robin Williams. There was an audience of thousands, and I was the only newbie. It was petrifying. I walked up three flights of stairs, on crutches, to center stage to represent the American Disabled Person. I went into my comedy routine, and nobody laughed. I was pouring sweat. I had tears in my eyes and I dropped the crutches, which was really dramatic, and said, “You know what? I think I need help.”

Everybody was staring at me. Norman came running down from the control booth and up onto the stage. He put his arms around my shoulders and said, “Geri, are you okay, sweetheart?” I said, “Norman, I’m fine, but the material sucks.” He put his hands on me and said, “Geri, your mic wasn’t on.” Nobody heard anything.

All the celebrities thought he’d just walk me off stage and I’d be cut from the final show, but Norman did the opposite. He got a working mic and asked the audience, “How many people in here want to give this girl a second chance?” I got a standing ovation, and he let me do the whole thing over.

Norman has been a surrogate dad for me throughout the years. He is always funny and always catches you off guard. My friend David Zimmerman and I interviewed him for Ability magazine, and that was also right around his birthday. We knew his favorite dessert was cheesecake from a deli in Westwood, so we got him the cake and we’re singing “Happy Birthday,” and instead of using his fork, he put his whole hand in the cake and put it in his mouth. It was so unexpected. —Geri Jewell (played Geri Tyler on The Facts of Life)

“Norman Lear is going to call you, and you have to act surprised”

When it came to 704 Hauser, Reuben Cannon was the casting director who had hired me in Amen and he said that Norman was doing a new show and that Isabel Sanford was going to be the lead, but they were looking for a neighbor and I would be perfect. I was doing theater in New York, and I couldn’t meet with Norman and I apologized. When the show finished, I flew back to L.A. and Reuben had left a message: “Norman Lear is looking for Lynnie. For the lead.”

I made an appointment. I was sitting on a bench by myself. Norman came down the hall, in his little white hat, surrounded by four people. He looked at me and said something to his line producer, who nodded. I later asked him on the set what he had said. It was, “She’s pretty, so I sure hope she can act.”

We go in, and he started talking about the show. He had such great vision about what he wanted to do. He wanted Rose Cumberbatch to be a religious woman. I asked, “What religion?” Norman said, “What?” I said, “Black people belong to a lot of different churches from Protestant to Pentecostal; my family was Pentecostal. Do you know what that means?” He said, “No, tell me.” And we had a whole conversation about it, and I realized because I was so specific about what I wanted this character to be and I was patterning her after my own mother, that I knew more about Rose than he did at that point.

My agent calls and says, “Norman Lear is going to call you, and you have to act surprised. He is signing you, not the network.” He liked to give the good news to people. Later that night, Norman called, and I acted surprised. So this is going to be the first time he heard about that.

On the set, it took me two weeks to call him Norman. It was “Mr. Lear.” He’d say, “Everyone should call me Norman.” And I’d say, “Nor … Mr. Lear.” But then I got there.

Norman taught me a lot. One thing is about being genuine and transparent. I’d visit him in his office, and one time his receptionist was going out to a store. The phone started to ring; as an actress I’d worked as a receptionist before, so I asked Norman if he wanted me to answer the phone and say, “Good afternoon, this is the office of Norman Lear.” He said, “No, I’ll get it,” and he picked the phone and just said “This is Norman,” and you could tell the other person was saying, “Wait, what?” Sometimes he could help the person calling, sometimes he could not, but he taught me that when someone calls you or emails you or texts you, answer them. Even if you can’t do anything for them or are just saying, “I’m not interested,” just answer everyone.

It was such a lovely experience being with Norman. He decided he wanted to create an aura about me. He’d take me places and introduce me as “the star of 704 Hauser,” and people wouldn’t know what he was talking about. I remember being invited to his house because he wanted to show his friends the pilot, and he said, “I want you to come and meet my friends.” I thought it would just be a couple of actors. I walked in the door and said, “Oh my Lord.” There was Gregory Peck and his wife, Quincy Jones, Maya Angelou. I felt so privileged that he invited me and introduced me to these people. I said, “Hello Mr. Peck,” and he said, “Call me Gregory,” and I said to myself, Yeah, right. Come on now. —Lynnie Godfrey (played Rose Cumberbatch on 704 Hauser)

“You’re in, kiddo”

I went to audition for 704 Hauser, but that week I had lost out on a part in Crimson Tide, a Taco Bell commercial that would have paid a hundred grand to shoot for two weeks in Hawaii, and a Diane English show. So I hadn’t even read the 704 Hauser script, even though I never told Norman that. That day I got a call from a friend from Chicago that her brother had just OD’d. I sat and bawled my eyes out, and I had to snap out of it and read the script right quick.

I go in for the audition, and Norman is sitting in the middle with the producer and the casting directors. I auditioned, but after that week and that morning, I rushed out thinking I wouldn’t get the part. But Norman says, “Wait. Can we talk to you?” He asked where I was from and some questions about my experiences, and he said something I’ve never forgotten: “This is a true case of an actor being better than my words. I’d like to thank you for coming in here.”

But after the pilot, Jeff Sagansky and Peter Tortorici at CBS wanted to fire me. I was 22 or so and they thought I looked older than the character; I had a receding hairline with them Sam Jackson cowlicks. After the pilot, I shot a USA Network movie of the week and shaved my head bald for that. When I saw Norman in the production offices afterwards, he said, “Kiddo, where’s your fucking hair?” He always called me “kiddo.” I said, “It grows back quickly, trust me.”

Then a week later he called and said, “Kiddo, I have good news and bad news. The good news is they picked up the show. The bad news is they want me to fire you.” They made Norman audition other actors. I went into a funk. I was depressed, I wasn’t eating. I was having my major shot yanked out from under me. Finally, I called Norman and they patched me right through, and I asked if I could get a shot at auditioning too.

Norman realized I was willing to fight for my job. He threw the resources of his company behind me. I would go in and read the new material with John Amos, [director] Jack Shea, and Norman and then Norman would go back and retool everything with the writers, and he’d tailor the material to my strengths. We did that for three days. Then he says, “Shave all your hair off again.” When I’m bald, I look younger. Now I’m completely bald, and I still get carded going to buy booze.

I go in and do my thing with John Amos the next day and walk out. About ten minutes later, I hear Norman saying, “Where’s kiddo?” And he walks into the room with that famous hat cocked on the side with his arms open and says, “You’re in, kiddo.” I’m choking up just thinking about that. —T.E. Russell (played Thurgood Marshall Cumberbatch on 704 Hauser)

“He will always reverse the spotlight. That’s just who he is.”

When I first got the call — “He’s thinking about maybe rebooting the show and wants to sit down and talk to you” — I went just because I wanted to meet Norman. You walk into his office, and it’s pictures of him with some of the most famous, most powerful people in the world, and yet to sit opposite him is to have his full attention. I was so moved, so struck by how present he was and how, in that moment, I was the most important person in the world to him.

Once I was there for half an hour and he said, “Well, we’re thinking about doing the show.” I was like, “Honestly, I don’t know that you should.” He goes, “What? Why not?” I said, “Because people come in and try to make content for Latinos, and we are not a monolith. We are a really diverse group of people, and when people try to make stuff for us, we feel when it’s inauthentic. When you finally get something and it’s not what you are, it’s hard because you want to be seen so badly.” He said, “Well, what do you think we could do to combat that?” I said, “I’m going to speak for this Latina in this family in this city and be super-specific. Hopefully that specificity will ring universal.” He was like, “Well, let’s just do that.” He made it sound so easy.

Over the course of our time together, he convinced me that in doing this with him, I would be in very, very safe hands. I had been a journeyman writer for many years on other shows, I’d been trying to find the right time and place to tell my story, and Norman not only heard me but said, “I will champion you every day.” And he did. When we would be on set those first episodes, people would go to him or go to Mike Royce and they would both say, “Don’t ask us, ask her.” I’d never been in a situation where that had happened. The spotlight was on them, and they shifted it over to the point where I was able to take up space in a way that changed my life.

When we shot the pilot, it was very emotional. My parents were there. Rita Moreno was wearing a wig to look like my mother. My parents came here in 1962 from another country, and they learned how to speak English by watching Norman Lear shows. The full circle of that night was tremendous.

I got really emotional with Norman. I was like, “Thank you, sir, for changing my life.” He kissed me on the forehead and said, “Oh, Gloria, it was just a matter of time.” What spoke to me about that moment is that even in complimenting him — and people compliment him all the time — he will always reverse the spotlight. That’s just who he is. —Gloria Calderón Kellett (co-creator and co-showrunner of 2017’s One Day at a Time)

“He was always a stabilizing force”

The first time I met him, I remember being in awe, even at that young age of 15, knowing that he was something special. I think it was my fourth callback for the show, and I sat right next to him at this big round table. I remember being very comfortable, which is not usual for those situations because I was really uncomfortable any time I had to go and interview for any show. We read it once and he said, “Well, try it again and do this, that, and the other,” and I was so raw and I didn’t know what I was doing. Now granted, I look a lot like his daughter, Maggie, is what he said, and I think that probably inspired him to give me a chance, knowing how green I was. I guess he saw something in me, and I’m glad he did because he changed my life.

There was even a point during the first season where he pulled me aside and he said, “Listen, we want to get you an acting coach to bring you out of your shell a little bit.” I had to cry in one of the last episodes, and crying was very uncomfortable for me on camera. Of course, in my brain, all I heard was, You’re terrible. You’re about to be fired. But he really was loving and wanted to help me. He knew that if I could not be so shy and just be more comfortable doing the work that it would be better for the show and it would, in the long run, make me a better actor. Norman said, “We’re gonna find you somebody to help you with the process of what it’s like to try and get to a place of vulnerability and still feel safe.” He really had faith in me when I never had faith in me.

As crazy and as horrible as Hollywood can be, I was extremely protected in every sense of the word. It was the kindest place to work. I learned so much and I never ever experienced a casting couch later, and I think a lot of that had to do with being taken under Norman’s wing. He was always a stabilizing force, for sure. When we were out in rough water, Norman would come to grab the steering wheel and calm everything down. He had it all under control in a way that was to protect all of us, starting with who we are, as people, not as a commodity. I felt like a real human being who was nurtured and treated with kindness. —Valerie Bertinelli (played Barbara Cooper in 1975’s One Day at a Time)

“He saw something in me that I certainly didn’t see in myself”

When I went in to meet with Norman for One Day at a Time, I remember going to this big office with this huge oval conference table. I’m 62, so I’m probably older now than Norman was when I met him, which is amazing for me to think about. I was coming right off American Graffiti, and obviously, he knew I had this crazy family. He said, “Mackenzie, America will one day realize this, but I’m gonna tell you this right now: Therapy is the backbone of a healthy family.” I think he was trying to give me some sort of hint, like, you know, “You’re gonna need some.” Certainly, in hindsight, it was an appropriate thing to say.

I remember conversations when we’d all be at the read-through table. We had older men writers — this was 1975 — and they sometimes would write something that they thought was “cool” for a teenager to say. Norman would always say, “Well, Valerie, Mack, if that’s not what a teenager would say, what would you say?” We had that freedom to say those things. There was a lot of give and take but it was always, always a group conversation.

Norman would be there for the first read-through on Monday and then new script pages would come in. They’re different colors — you get pink pages, then blue pages, then you get goldenrod. But midweek, one would come down, and it would be a full script. The cover would be yellow, and in the upper lefthand corner, it would say “Lear Polish,” which meant that Norman himself had taken the script and shined it up. I was always excited when we would get the Lear Polish. And I actually still have — God knows how after my crazy life — all of my scripts from One Day at a Time with my lines marked and “Lear Polish” in the upper lefthand corner.

We always had a network censor at run-through, and Norman fought them tooth and nail. You were allowed to say “jackass” but you couldn’t say “ass,” and Norman just thought that was ridiculous. He advocated for stuff that wasn’t allowed on TV. We were portraying and representing a very underserved and large portion of the American population — the single mom. To this day, all these years later, I have women, and men, come up to me and say, “You were the only show that represented what my family looked like. You made it okay for me to go to school and be part of a divorced family, living with a single mom.”

Norman had a curiosity about what isn’t being done that should be done, what isn’t being represented that should be represented. I don’t think his goal was to piss people off. Well, maybe it was, knowing Norman. But he wanted to shake things up. He wanted to push the envelope. He wanted to bring a voice to communities that weren’t represented as worthy of having a voice.

Over the years, all through the years of my struggles, whenever I would see him at an event, he would grab me by my face, gently, and say, “That punim, look at that punim! I’ve known you since you’re a baby! I love you.” That friendship was a slow growth because I would see him in passing, and sometimes I would be in a stage of recovery and sometimes I wouldn’t. Now, when I see Norman, I feel as though he has a deep respect and trust and admiration for me, as I do for him. It’s more of two grownups interacting. When I was 40, I still felt like a child around him. I don’t feel like a child around Norman anymore. He saw something in me that I certainly didn’t see in myself. He’s just a good man. —Mackenzie Phillips (played Julie Cooper in 1975’s One Day at a Time)

“Here is this titan of industry respectfully listening to a tweenager tell him about her unicorn scribbles”

The thing I’m most grateful for is that Norman encouraged me to write. I used to carry a notebook and pen around with me everywhere, filled with doodles and stories. Norman once asked me about it, and I bent his ear about my angsty teen poetry and short stories about mythical worlds with magical beasts. Here is this titan of industry respectfully listening to a tweenager tell him about her unicorn scribbles. More than that? He encouraged me to keep writing, take classes, and tell him what I was working on the next time I dropped into his office unannounced.

When Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman came back from hiatus to start season two, there was something special in my schoolroom on set: Norman had sent over a top-of-the-line IBM electric typewriter, the kind only legal secretaries used. Now here was a magic beast in real life! Suddenly, I had a way to get the thoughts in my head onto paper as fast as I could think them. The machine was wonderful, but the thought behind it gave my confidence enough of a boost to call myself a writer. I had few role models in my life, but Norman was kind and I glommed on to him, seeing him as the grandfather I never had. I can draw a straight line from Norman encouraging my writing, and telling me to believe in myself, to my 25-year career in radio. —Claudia Lamb (played Heather Hartman on Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman)

Norman the Clown

“Who is that old guy?”

When I started working with Norman, he was only 93 years old. We were working on a docuseries on inequality. The initial idea was to bring him on as executive producer.

This was a celebrity-correspondent-driven docuseries, so we got the idea of putting him on camera as a correspondent. Once he decided to be part of it, whatever we would ask he would do. He was into it.

Norman came to New York City to investigate housing inequality, exploring gentrification and outright discrimination. He was the perfect correspondent. When I asked when he’d want to see a cut, his answer was, “Whatever works for you,” which no correspondent — especially famous ones — ever says. He was very at home on camera. He’s extremely comfortable in his own skin without being conceited or a peacock.

He visited a low-income Brooklyn neighborhood, and he sat in the lobby of an apartment building with a group of elderly Black residents, who were having major problems with their landlord. They went around one by one, introducing themselves and saying how long they’d been in the building, and when it came around to Norman, he didn’t miss a beat and said with perfect comic timing, “My name is Norman, and I’ve been in this building about ten minutes.”

We sent him a rough cut of some footage, and he said, “It’s really good, but who is that old guy?” —Solly Granatstein (executive producer of America Divided)

“There was no sense of ego”

Marta Kauffman and I were were musical-theater writers in New York, and we’d been going back and forth to L.A. trying to sell scripts. His company, Act III, gave us our first development deal; they flew us out and we moved to L.A. to work for him in 1989.

When we met him, he couldn’t have been lovelier. We were in his office, and Marta noticed a picture on his desk of Norman from much earlier, back when he had hair. She made some sort of a comment, and he said, “I was just starting to go bald … like David.” It was the first moment I found out I was starting to go bald. I truly had no idea. It took me another 30 years to lose the hair, but he was right. And no, he did not give me one of his hats.

When we created The Powers That Be, it gave us a chance to really work with Norman. I’d always been a huge fan of his, but we have very different sensibilities. But he was incredibly generous even though we were brand new and had done television for five minutes. He treated us with respect and listened to our ideas. There was no sense of ego. —David Crane (co-creator of Friends with Marta Kauffman)

“Think of the publicity we would get!”

I first met Norman years and years and years ago. They were holding auditions for a pilot that he was going to shoot with Charles Durning, and they were seeing actresses for the role of his wife. I came in looking spiffy and very cute, and he took one look at me and said, “You could never be Charlie Durning’s wife in anything.” I said, “What!?” and he said, “Rita, how old are you?” I said, “I’m 66,” and he said, “You don’t begin to look your age. You’re also very cute, and that’s okay, but you could just never be Charlie’s wife. Now get the hell out of here.” Of course, it’s true I’ve never looked my age — I mean, I’m catching up now — and I went to my car and sat and cried for like an hour because I hadn’t worked in at least two years. I didn’t look young enough to be a young wife, and I certainly didn’t look old enough to be Charlie Durning’s wife. I truly wept bitter tears.

I later brought up that first meeting to him, and he had no idea what the hell I was talking about. Then he said, “Oh, the one with Charlie Durning.” I said, “You have no idea how that affected me!” We talked about it, and he said, “Well, you know, that makes sense to me. You were pretty! Not that there’s nothing wrong with being pretty, but it was just a kind of pretty that I just felt you would not have looked right for his wife.”

Then I ran into him at a dinner, and he said, “I have a pilot that I’m going to do and I would love to have you in it. Would you be interested?” I said, “Yeah. But wait a minute. What is it about? I mean, am I gonna be dancing naked somewhere?” He said, “Oh my God, no, no. I have this marvelous series, One Day at a Time,” then he explained it and it sounded wonderful. That’s the second time I met Norman Lear.

When we spoke on the phone about the role, I said, “If I am to do this part, there is one real caveat. You must say yes or I’m not interested. She has to be sexual. The idea that she can no longer conceive is meaningless. She has to be a sexual person.” And boy, did they run with that. There were times when they gave me stuff to do and I said, “Are you serious? Can we get away with this?” She’s always talking about her husband and how they love to shtup, which I just adore. It’s one of the things that people just were crazy about when it came to Lydia.

It’s sort of like All in the Family. All I could think was, How do they get away with this? I was shocked, absolutely astounded that they could even get any of those things on the air. He’s always been so forward-looking and very courageous. On the other hand, I don’t know if that word really applies because in order to be courageous, you have to be afraid. At least that’s how I see it. And I don’t think Norman was ever afraid.

Norman is a very, very mischievous guy. During the second year of One Day at a Time, he called me one night and said “I have an idea. I think we could get a lot of publicity with this. Let’s spread a rumor that you’re having my child, my love child.” I said, “Norman, my ovaries are over and done with! They were over and done with years ago!” He said, “It doesn’t matter. Think of the publicity we would get!”

He was laughing — he wasn’t dead serious, but he was, you know? From then on, that crazy old fart, he started spreading this rumor that I was carrying a child. After a while it did amuse people whenever it was brought up. I decided to call the child Moishe, very Jewish. It was either that or Shlomo.

One year, I made a little video for him for his birthday or something and I said “Oh, by the way, Moishe’s here. I think you should say hello to your child.” I signaled, waved my arm, and said “Moishe, come over. It’s your dadda. Come on!” I kept telling him to come and he wouldn’t. I said, “He just won’t come. He’s playing,” implying that the child was masturbating. I said, “Oh God, he does this so much. It’s just maddening.” This is how we are with each other. We’re like kids. —Rita Moreno (played Lydia Margarita del Carmen Inclán Maribona Leyte-Vidal de Riera in 2017’s One Day at a Time)

“From the very beginning, Norman was not on board with this episode”

Norman was such a great supporter of everything Gloria and I were doing, but in the beginning it took time for him to get used to everything not going through him. He used to be a guy who sat at a table and they brought six shows by on the hour for him to lead. Also, we were rethinking a project of his that was a famous show, and he wanted to make sure it was in the right hands.

The first few episodes were him watching us closely and offering opinions when he had them. But the fourth episode was a departure. We did a script that was a little more How I Met Your Mother–ish that went back and forth in time.

From the very beginning, Norman was not on board with this episode. We said, “Trust us, we really believe in it.” He did, but he was like, “I just don’t get what you’re doing with this. I don’t think it’s going to work.” Even after the table read: still skeptical. We got to the first run-through — and it went well. It went very well. Gloria and I were happy. And then we see Norman coming over to us, and he kind of points his finger and goes, “You two, come here.” We were like, “Oh, shit.”

He takes us over to another set so he can have a private chat with us, and we’re like, “Well, this can’t be good.” He sits us down and he says, “From the beginning, I told you this episode was not going to work.” Then he takes a big pause and he goes, “But you live and learn.” And then he couldn’t have praised us more.

First of all, the reality-show setup of the whole moment — where he took us in one direction then did a 180 on us? It spoke to his incredible forbearance and generosity that he, first of all, let us go down this path he wasn’t quite on board with and then had the wherewithal to tell us, “Basically I was wrong, and I am so pleased by what you’re doing.” I think that was the moment he could trust us. It was a very big moment in my life, to have a legend be like, “I don’t think it’s going to work,” and then tell you, “You know what? It does work.” —Mike Royce (co-creator and co-showrunner of 2017’s One Day at a Time)

“I have no fucking idea who you are, honey”

He’s always dropping F-bombs right when you least expect it, especially during moments of deep affection. He’ll call you on your birthday and say things like, “I love you to bits and I don’t care who the fuck knows it!”

We didn’t want to make a film about him if he had editorial control, and he agreed to that. He didn’t have to — he could have gone with another filmmaker, so it really showed a lot about his love, his respect for the craft of filmmaking.

We were very, very nervous showing him the movie. We wanted to show it to him when it was finished before the Sundance premiere, and he came to New York to see it. We rented a cinema, and we’re sitting there trying to watch him while he was watching. There are all these flights of fancy — there’s a child who plays him and we’d done a lot of lyrical things — he was in the war so his airplane becomes a hawk, and he’s at Coney Island and there are these ravens flying by. There’s a lot going on in this movie.

He had two comments at the end of the movie. One was, “You definitely have got to lose some birds.” This is an entire movie about his life. It’s emotional, and he was just like, “There’s just a couple too many birds, ladies.” He was entirely correct, but it was the last thing I thought he was going to say after watching an entire biography of his life that he’d never seen before.

The second thing, the only change he asked for, was this moment when we were filming his family at Thanksgiving. He said, “A couple of the kids aren’t in the shot. I’ve got to have all my kids. Can you use a photograph, at least? Please, is there any way?” He just wanted to make sure all the people he loved were seen at least once in the movie.

When the movie premiered in Los Angeles, we were doing Q&As for both sold-out screenings. At one, this woman stood up who’d gone to grade school with him like 80 years ago. She gives this gushing speech, “Norman, I always remember this and this about you. You’re such a memorable person. Do you remember me?” He goes, “I have no fucking idea who you are, honey. But I’m so glad you came!” It was brutal honesty, but nobody was mad about it. His timing is impeccable.

I used to always joke that only the mean people live to be 100, because I’ve met a lot of people who have awful, awful parents, and they live the longest. Now I don’t say it anymore, because the oldest person I know is a total mensch. My oldest friend is Norman Lear, and he is the truest mensch that I know. —Heidi Ewing (co-director of PBS American Masters documentary Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You)

“He just dropped the mic”

In 2016, at the height of all the election craziness, we were at a screening for the film we made about him. It was the first time he was meeting my son, who was like 8 at the time. I went to introduce them, and my son said, “Mom, how do we know burning sandals?” Norman goes, “Who’s burning sandals?” and I said, “He means Bernie Sanders.” Norman just died laughing. He delighted in that so much. And when he stopped laughing, he said, “You got the wrong progressive Jew, kid.”

He’s a real progressive. And when I say progressive, I don’t mean with a big P. He’s interested in the future and he’s flexible with change. You can change his mind, which is a wonderful quality in someone. You see people get less and less open-minded as they get older. I’ve known him for almost all of his 90s, and he’s gotten more and more open-minded. I think it’s what keeps him alive and bright: this passion for knowledge and meeting new people and getting new perspectives.

At one of the screenings of our movie, Hasan Minhaj was the moderator for a Q&A, and he told a very intimate five-minute story about what Norman meant to him, how his immigrant father never thought he should be a comedian because that was not a real job. He was always struggling with his dad and then he met Norman at some event and mentioned something about it to Norman. Norman told him, “Call your dad,” and gave him this salient advice. It gave Hasan this huge confidence boost.

Hasan went back to his dad and they had this conversation, and their relationship has been on the right track ever since. It was just like this big thing that happened, and Norman doesn’t say anything the whole time he’s telling the story. Finally, it was his turn to talk, and Norman said, “I thought you looked familiar.” He just dropped the mic. —Rachel Grady (co-director of PBS American Masters documentary Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You)

“They ad-libbed for the rest of the movie, and it was hysterical”

We got to know each other well and were always very close. Marilyn was very close to his wife, Frances. Our kids grew up at the same time. He had a wonderful screening every Friday night that we were invited to. He would show whatever movie hadn’t been released yet and wonderful people were there: Mel Brooks and Anne Bancroft, Carl Reiner, Joan Didion, John Dunne.

One of the funniest moments was when there was a movie John had to review. He asked if he could show it, and Norman said, “Of course.” It took place in a restaurant, and halfway through, there was a feeling that this was not an amusing or interesting movie. So without anybody saying anything, Carl and Mel took little chairs, put them next to the screen as if they were the next table over to what was on the screen, and sat down and started to ad-lib. Then Norman put a towel over his right shoulder and he became the waiter. They ad-libbed for the rest of the movie, and it was hysterical. I still laugh at it. Mel and Carl were just hilariously funny.

I’m 96 years old. And as I am, he’s working every day, writing. That’s what we do. We see each other once every few weeks, and we just talk. And not about the old days — we’re talking about the new days. He’s so gifted and open and aware of the world — not only as far as show business is concerned, but politically very aware and wanting to be involved.

Besides being funny, his shows all have had something to say about life and all phases of life. He was so ready for anything that was different, new, interesting, and imaginative. The love of life and creativity was there all the time. He used them as a commentary on life. It was not just to get laughs. The truth has no boundaries as far as generation is concerned. And what he dealt with was the truth. —Alan Bergman (co-writer of the Maude, Good Times, and All That Glitters theme songs with his late wife, Marilyn)

Norman the Legend

“You’re going to buy a wig, and you’re going to pay for it”

It’s very rare when you get to work for someone like a Norman Lear, an innovator who changed the face of television. We laughed a lot together. He found some of the things we did on the show, as per his instructions, so hilarious that he broke up laughing, and I did as well.

With all due respect to our writers and to Norman, none of them had lived or were that terribly conversant with life in the Black community. The mores and values we placed on life and family gatherings and relationships were contrived or misconstrued in the white community. Without any Black writers on staff, we had no representation that could speak with an honest voice about situations that would come up in the everyday life of this family in the community at Cabrini-Green projects. I felt it was up to me and the other actors in the cast to speak up and rectify the situation. I felt very comfortable doing so because I started in television as a comedy writer before I became a performer.

I remember him being receptive. For him, it was an educational process. And for us in the cast of Good Times particularly, it was an educational process. We were learning what would fly on television, how to voice your objections or your commendations or your applause or whatever comments we had directed toward Norman’s scripts. We were allowed to do so and say so, so we had complete artistic freedom on the show. That was a rare situation.

We had our differences during the course of Good Times and some of the subsequent shows. We were both very passionate about our respective positions in regards to Good Times. We found that if we became more receptive to other people’s objections or their observations, things would go a lot smoother. In time, we made up our differences, rectified whatever problems we thought we had, and went on to have a good relationship.

When Norman and I got together again, we did 704 Hauser. 704 was, of course, the Archie Bunker household. I don’t know what possessed me to do it, but I came in one day when we were about to tape the show and I had gotten a severely different haircut. Well, Norman took one look and said, “Oh, no, this will never do. You’re going to buy a wig, and you’re going to pay for it.” And I did. He made me wear the wig in the show so it would match the previous footage of James Evans with his head of hair. That let me know he was adamant about having his characters stay the way they had agreed to portray him and not make changes in the middle of the stream.

If you knew Norman, you know that when he laid down the law on something, it was laid down. There was no broaching it. We had to do it his way. Because invariably, it was the right way. He was right about that — I don’t know what possessed me to get that haircut that way. I think I was just being recalcitrant. It was another example of working for someone who has strong convictions about his vision as to what he wanted his project to look like, and I had to adhere to his wishes. So it worked out all right. It worked out just fine.

We got back together again and had a reunion after all those years on his live show. That was the most unusual thing in my career: the fact that I got to play opposite a wonderful actor, Andre Braugher, who was portraying James Evans. I was overjoyed to be working with Norman again and it was a way of paying tribute to him, to let him know that he had been the guiding force in my career.

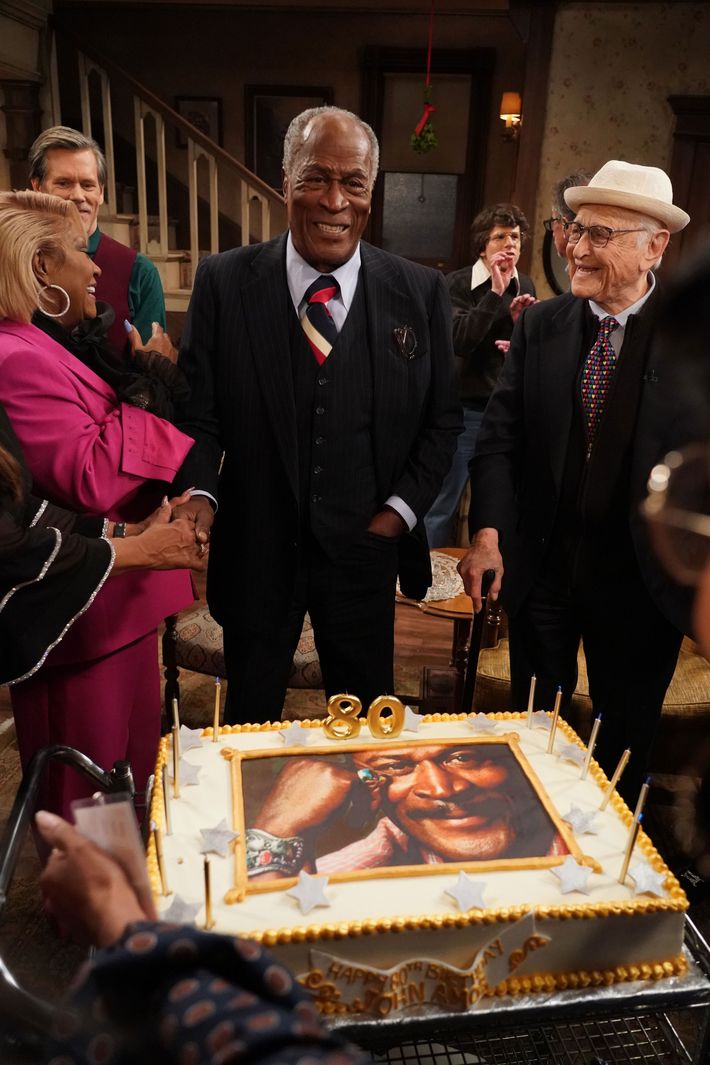

Norman did not bite his tongue about the things that he was passionate about politically and socially. He was able to address issues like teen pregnancy, teen drug use, gangs, and all the subject matter that was virtually ignored on other programs and other networks. He addressed it head-on and did so very, very skillfully and sensitively. I was grateful to be working for someone who was going to use the greatest medium of communication the world has ever known to rectify some of society’s problems — or to attempt to, at any rate. He was courageous in that respect, and his courage paid off by the audiences that gathered for all his shows. —John Amos (played James Evans Sr. on Good Times and Ernie Cumberbatch on 704 Hauser)

“He was fully a member of their family”

I was very intimidated. It was Norman Lear plus Rita Moreno and the rest of the [One Day at a Time] cast. You don’t want to mess that up. Norman was so gracious and cool. You’d expect someone at 97 to be just a figurehead, but he wasn’t. He was more than just a participant — he was fully a member of their family. It was really special to see.

I went to Emerson, where he went, so people make a huge deal there about him — as they should. I’d never heard of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman before that. I’d watched All in the Family and The Jeffersons and Good Times growing up in reruns, so I knew a lot of his work. But Mary Hartman completely blew my mind. It’s an amazing satire, and it takes women and mental illness seriously. It’s my favorite thing ever.

So at the end of the interview, I mentioned that I went to Emerson and said, “Hopefully this means I can say a couple of sentences more,” and I asked about Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, because it’s still unlike anything I’ve ever seen. He was so, so nice, he seemed really happy and excited that someone in their 20s knew about the show. He told me about the history of the production and said he would love to bring it back one day. If there’s anyone who is going to do it at that age, it would be him. —Jamie Loftus (comedian and podcaster who interviewed Lear at Vulture Festival in 2019)

“I was really grateful to have his blessing”

The first time I met him, he came to The Carmichael Show to check out what we were doing. He watched our taping and hung out with us afterward to talk shop. It was such an honor to have him care about what we were making.

We all sat as a group, and he shared why the medium was important and a great way to tell these important stories. He’s lighthearted and nothing was too serious, but he wasn’t cracking jokes — it was more of a thoughtful conversation. He was so friendly and gracious and would look you in the eye and say, “You’re doing a great job.” I was really grateful to have his blessing.

Then I was lucky enough to be in the one-night special of The Jeffersons, and I got to spend some time with him then. We had dinner at Jimmy Kimmel’s house with all the actors before we filmed, and he stood up and gave us a speech about how special it was to him that we were reviving these stories. Again, a gracious and down-to-earth person who cares about telling important stories. —Amber Stevens (played Jenny Willis Jefferson on Live in Front of a Studio Audience in 2019)

“I can’t even track where his influence begins because there’s so much of it”

I had the privilege of speaking at his Kennedy Center Honors, and I introduced the show Maude. We had just done an abortion story on Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, and it’s a testament to Norman, because he set a precedent for it. Not being afraid to tackle an issue and finding ways to do it and still make people laugh, he manages to do so well.

It was a very surreal night. I got to be backstage with him, Carl Reiner, and Rita Moreno and watch them interact. He’s made so many important careers and influenced television so much, to the point where the things that influence me come from people who are influenced by him. It’s almost like I can’t even track where his influence begins because there’s so much of it.

Something I learned at the Kennedy Center was that he’s a World War II veteran but also used his own money to pay for one of the original copies of the Declaration of Independence so it could be toured around the U.S. This idea of patriotism, which has been so co-opted by the right — the right says, “We’re patriotic and people who are left-wing aren’t” — like, no. Norman Lear is one of the most patriotic people, and writers, ever. And he’s a lovely person. —Rachel Bloom (co-creator and star of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend)

“Nine times out of ten, it was Norman who found the joke that worked better”

I grew up in front of a TV set, and in the 1970s, television was the Norman Lear Show. I used to see the words “Created by Norman Lear” so often I didn’t realize he was actually a person, I thought it was just a slogan for TV, like “In God We Trust.” You can look back to Sid Caesar and imagine what television back then must have been like, but with Norman, he’s a living person who can talk to you about the beginning of television. I think he was the first professional television writer who did not come over from radio.

I had met Norman at random industry events and in the social-justice world, but I got to know him when we worked together on One Day at a Time. You don’t have to draw anything out of Norman; he is an extrovert. No matter the topic, he is always funny. He respects comedy as a vehicle for talking about tougher, more challenging ideas.

I didn’t expect him to be as hands-on, but he was at every table read and every live taping. He would warm up the audience before each live taping. On my office wall, I have a picture of Norman warming up the crowd before the first episode. You can see the look on everybody’s face — first that he even showed up and then that he’s so funny. Throughout the taping, they’re testing jokes, and if a joke doesn’t get a laugh, the writers would huddle to fix the joke. Nine times out of ten, it was Norman who found the joke that worked better.

When it comes to cursing, he knows how to add just the right amount of color to a sentence, and it always catches you off guard because he is so eloquent, but he understands exactly how much of the cursing to use.

People also don’t think about this, but Norman is spiritual: He’ll break down the moment you are in right then and all the series of things that had to happen to put you at that table with him in that moment, and how miraculous the world is that all those things lined up so we could be sitting there. Norman takes nothing for granted, and that’s been true for as long as I’ve known him.

Every single time I talk to him, at the end of every conversation he says the same thing, and it’s a line that is such a great reference to his life on TV but also speaks volumes to his optimism. He says, “To be continued …” —Ted Sarandos (Netflix co-CEO and chief content officer)