This article originally ran on October 19, 2022. We’ve republished it now alongside Episode 3 of Land of the Giants: The Disney Dilemma, a Vulture-Vox Media Podcast Network collaboration that looks at the many facets and ever-changing fortunes of the sprawling entertainment company. You can listen to it here, and follow the entire series at the Disney Dilemma hub.

When watching Lilo & Stitch — be it for the first time or the 40th time — it’s always a bit of a surprise to discover that it starts in the farthest reaches of space, at the Galactic Federation Headquarters on the Planet Turo. One forgets that the 2002 Disney film, written and directed by Christopher Sanders and Dean DeBlois, is, technically speaking, science fiction: the story of an incredibly powerful and destructive experimental creature, engineered by a mad scientist from an alien world, who crash-lands on Earth only to find a loving family in Hawaii. That jarring discrepancy between the movie’s grand interstellar framework and the gentle, intimate, even understated nature of its story is part of the unorthodox charm of Lilo & Stitch, a picture so wonderfully strange that it’s hard to believe it ever got made.

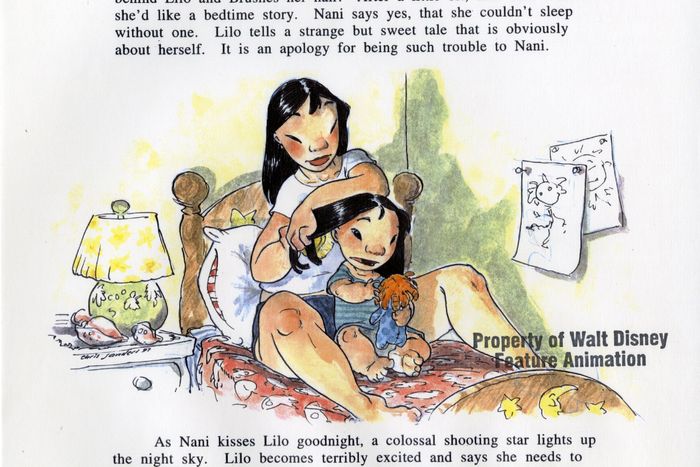

Visually, the film is a wonder. The rounded characters, based on Sanders’s designs, stood in sharp contrast to the exaggerated Disney aesthetic of the times. The watercolor backgrounds — utilizing an extraordinarily difficult painting format that hadn’t been seen in a Disney feature since the 1940s — add a dreamy yet tactile mood to the proceedings. But what makes Lilo & Stitch so indelible is the way it tells a story that, for all its sci-fi ornamentation, focuses largely on characters who look and feel like ordinary people with real-world problems. Yes, there’s a demonic agent of chaos with six limbs and a mouthful of huge teeth. Yes, there are spies from outer space (one with one eye, the other with four) hunting him down. Yes, Ving Rhames shows up voicing a riff on his Pulp Fiction character. But somehow everything comes down to the moving idea that you make your own family, and that family means no one gets left behind.

This film is the strangest and most delicate of combinations. Even the people who made it still marvel, 20 years later, at what they were able to pull off with little money and time. Lilo & Stitch was made far from Disney headquarters in Burbank, California, produced almost entirely at an animation studio in Orlando, Florida, with a group of young, hungry, close-knit artists eager to prove what they could accomplish. What they created wound up being one of the few bright spots of the early 2000s for Disney, during a period of intense soul-searching and infighting at the company. It remains, to this day, one of Disney’s most beloved films.

I. “I think these have gotten too big.”

While the 1990s saw such runaway successes as Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King, the latter half of the decade found Walt Disney Studios starting to worry about the direction of its animated productions. Jeffrey Katzenberg departed in 1994. Over the next several years, expensive titles like Hercules and Fantasia 2000 didn’t manage to live up to box-office expectations, while others films seemed to be stuck in development. It was in this environment that the animation house decided to make a smaller, more personal movie, produced on a lower budget at the company’s studio in Florida, which opened in 1989 and and had already distinguished itself with their work on Mulan (1998). Tapped to direct the new production was Christopher Sanders, who had co-written Mulan and had also worked on Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King. Joining him was Dean DeBlois, who had worked closely with Sanders as co-head of story on Mulan.

Thomas Schumacher (creative executive at Disney): The whole thing started in 1997 at Michael Eisner’s family farm in Vermont. About 21 people attended, including Roy and Patty Disney, Peter Schneider, and me. We picked apples, we carved pumpkins, and we talked about animation. The idea was, Let’s make the Dumbo for our generation. A director-based film that wasn’t huge and complicated, and therefore would give the animators more control over it.

Chris Sanders (co-director, co-writer, and voice of Stitch): Seventeen years prior to me even pitching Lilo & Stitch, I wanted to do a children’s book about this little creature that lived in a forest. It was a bit of a monster with no real explanation as to where it came from. It was all about how he found a way to belong. But after doing a couple of drawings, I realized the idea was going to be very difficult to squeeze down to, say, 24 pages. So I abandoned it.

Schumacher: Chris was extraordinary. Chris created amazing things. He did “I Can’t Wait to be King.” He was head of story on Mulan and did one of the best sequences — the whole thing where her dad picks the blossom and says, “The flower that blooms in adversity is the most rare and beautiful of all.” He created the crane game for Toy Story. That Calvinist thing: “I have been chosen.” That’s all Chris. So I went to Chris and said, “Everybody wants this next film to be you.”

Sanders: That’s when I pitched the film for the very first time. It was all set in the forest with animals.

Schumacher: The two things I said to him were: “You don’t want him to be living in a world full of animals who don’t know what an alien is. An alien among animals is not as remarkable as an alien among humans.” Also, I said, “The forest is just green on green on green.” I said, “Visually, imagine color.” I initially suggested Tahiti. I’ve always wanted to go because my great-grandmother was born in Tahiti.

Sanders: I had a map of Hawaii up on my wall. I’d been on vacation there. One day I thought, Wait a minute, why couldn’t I just set it there? I didn’t know anybody at that point who was Hawaiian that I could consult with, so I turned to a roadmap and I just started pulling names. I found Lilo Lane and I found the word Nani on there, and these sounded like names to me.

Then I went away to Palm Springs and spent a week holed up in a hotel room. I thought, If I say “alien,” everyone’s going to have a different interpretation as to what that is. So I’m going to do a book that has drawings in it so they understand. I created, in a sense, that children’s book. I drew Stitch and I tried to build a model of him. It was this conglomerate of different animals. I had some pieces of crab that I had bought at a seafood place. I made a clay head. I found some glass eyes at the taxidermy shop. I brought that back from Palm Springs and gave it to Tom and the development department. That’s when Tom bounced back and said, “I’ll do it if it’s in your style.”

Dean DeBlois (co-director and co-writer): Tom Schumacher and Peter Schneider were charmed by the book and said, “We will make this at a lower budget. The condition is you have to go back to Florida” — where we had just finished up Mulan — “and use that studio to produce it completely.” Florida was mostly a satellite studio at that point.

Sanders: I knew that that was the right place. That studio was like what Disney studios was back in the ’30s, back in the ’40s — young artists who were hungry, who were driven, who wanted to prove themselves and who were immensely talented.

Pam Coats (senior vice-president of creative development at Disney): Part of the joy of the Florida studio was that it was on some level tucked away from the everyday. It was out of sight, out of mind.

Sanders: I remember going to the Hercules wrap party, which was gigantic. I ran into Michael Eisner. I like Michael a lot, but we don’t have a lot in common. He’s super-nice and a fascinating person, but he’s really into hockey and I don’t know anything about hockey. So we talked for a little bit, and then Michael said, “Well, I guess I better go out and mingle.” And he left. It wasn’t very long before he came back, and he’s looking around, and he said, “I don’t know anybody here. I think these have gotten too big.” He was echoing something that I was feeling. Things had gotten bigger and bigger and bigger. But the bigger they got, the more unwieldy. You have bigger budgets, but that meant that you had to be, in a weird way, more careful.

DeBlois: This film would be made off the grid, away from the watchful eyes of the Disney leadership.

II. “We were the equivalent of a spy plane that was being built at a secret hangar with a very elite group of people.”

Disney animated productions famously took years to get made, usually after many rounds of screenings, notes from studio leadership, and rewrites. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s, a number of expensive Disney projects were in disarray: Treasure Planet; Kingdom of the Sun, which would become The Emperor’s New Groove; and Sweating Bullets, which would become Home on the Range, among them. The pains associated with corporate meddling understandably made writers, animators, and directors nervous. Christopher Sanders himself recalled several encounters at Disney’s screening room in New York City that pretty much scarred him for life. “Nothing good ever happened in that room,” he says.

Sanders: Jeffrey Katzenberg once flew me out to New York City because he wanted us to do West Side Story with cats. I boarded this huge sequence where these cats were battling each other. Jeffrey said, “We’re going to fly to New York, and you’re going to pitch it to Leonard Bernstein.” All of a sudden, I was on Disney’s corporate jet. I went to the room and I set up all the boards, and I practiced and I practiced and I practiced. As it turned out, Leonard Bernstein didn’t show up for the meeting. He sent representatives. I’m sure they were people of some prominence; there was one woman in particular who had a lot of necklaces on. But you could tell it wasn’t going well. Like, Oh, I think we may have made a mistake by coming here.

Schumacher: There was another moment that probably informed Chris. At the end of Mulan, she says, “Father, I bring you treasures from the emperor to bring honor to the Fa family.” She hands him all this stuff, and he throws it on the ground. He grabs her, hugs her, and says, “Having you as a daughter is the greatest honor of all.” It makes me cry every time I watch it. I’m actually tearing up telling you the damn anecdote. We screened it in New York for Michael Eisner. And Mulan didn’t nudge Michael at all. At the end, he literally screamed, “Who’s the guy on the bench?!” Chris was sort of jumpy about Michael’s notes after that.

Sanders: I happened to sit right behind Michael Eisner at a Lion King screening. He’d had a very difficult morning. We’d heard about it before: “He’s had some bad meetings.” Everybody had a light-up pen, so you knew when somebody was making a note because you’d hear a click and a little light would go on. I was waiting for Michael to write stuff down. But I think he was just consumed with what had happened earlier in the day. When he was watching the film, he would put his head down and he’d look to the side, and then he’d put his head down again, look around, and put his head down again. He kept doing that through the film. At that pivotal moment — when Simba has grown up and runs into Rafiki, who tells him to look into the water. Simba says, “I see nothing.” Rafiki says, “No, look harder.” At that moment, Michael Eisner looks down. So Mufasa’s ghost appears, and he says, “Simba, you are more than what you have become. You are the one true king,” and Michael looks down the entire time. Mufasa says, “Remember who you are.” The clouds recede. And then Michael looks up. We went to the meeting afterward, and Michael said, “I don’t even know why Simba went back home.” I couldn’t stand up and go, “He missed it! He didn’t see it!” Jeffrey Katzenberg says, “Well, Mufasa’s ghost came back for him.” Michael goes, “Oh, I didn’t get that at all.” Jeffrey’s like, “How could you miss that?” Michael’s like, “I don’t know. I just didn’t see that. What happened? Mustafa who?”

That’s the kind of thing that Lilo & Stitch never went through. Whenever Tom would go to his numerous meetings on the main lot and Michael Eisner was in there, they’d be going down their agenda. He’d say, “So what is this whole Lilo & Stitch thing?” And Tom would say, “Oh, it’s this thing that we’re doing. It’s not really ready yet, but when it’s ready we’ll show you.” Again, I like Michael, but the film defied conventions, and they would have tried, likely, to put it into a mold that they were more familiar with. How do you sit there and explain, “Well, I think it’s really cool that the girl feeds peanut butter to a fish”?

Schumacher: When Dumbo was made, Walt was in South America. He was not around when Dick Huemer and Joe Grant were doing that movie. Roy Disney was in the room a lot with Lilo & Stitch, but Roy was an extraordinary fan and a great supporter. He would just come in, give a note, leave.

Clark Spencer (producer): Tom really knew the right moments to bring people in. The moments when people would be able to see where the movie was headed and give the notes that would actually elevate it, as opposed to cause people to say, “Well, what if it was something entirely different?”

Kevin McDonald, voice of Pleakley: Now that I’m an old man and I bring every conversation back to myself, here I go: The Kids in the Hall were like that! On our original series, we were in Toronto, and HBO very rarely flew up to see us. Lorne Michaels only made the flight once a year. That was mostly to see his family because he’s from Toronto. So we were hidden like that, too.

Sanders: We were the equivalent of a spy plane that was being built at a secret hangar with a very elite group of people. And that’s another reason that Florida was magic, because no one knew what was going on in Florida.

Lisa Poole (associate producer): Being in Florida, you were away from the mothership. If you needed support from L.A., you had to holler a little louder. But that gave us freedom. There were definitely some things we did differently. And when L.A. found out, they didn’t like that we were doing it differently — but they couldn’t argue with the results.

III. “We have no business telling a Hawaiian story.”

Sanders had set Lilo & Stitch in Hawaii, but he and DeBlois understood early on that they were outsiders seeking to make a film about a specific culture, and that for too long, Hawaii had been a pretty and exotic backdrop to stories about characters from the mainland. It was important that Sanders, DeBlois and their team did as much research as possible and worked with individuals from the community to create an authentic sense of the place and the people. Their research trips to Hawaii were eye-opening, and changed the course of the film visually, musically, and narratively.

Ric Sluiter (art director): When I stepped off the plane in Hawaii, I couldn’t believe how pure and clear the colors were. Being out on an island, there’s no smog. The greens were greener, the fuchsias were more fuchsia, the skies were bluer. Being an art director and working in cities and stuff like that, I’ve never seen color like that.

Sanders: Our artists were traveling all over the place in Hawaii with their easels and their paints, because a photograph will never work. You have to go on-site and paint the actual things so you come back with the actual colors. They were collecting stuff that became the vibe of the film and making very careful observations architecturally. What the curves look like, what the window frames look like.

Sluiter: The sand is very iron rich. You walk on the beach and all of a sudden it looks like a giant dropped a bag of potatoes, but they’re lava rocks and they’re just piled all over. One day we were sitting on the beach at night having dinner by the ocean. The sun was setting and the waves were coming in. The water was turquoise, but the sea foam was pink. “How can the white foam be affected that much by the color of the sky, but not the water?” You’ll see in the surfing scene, we did that. Most people would’ve just done the water with white foam or grayish blue foam. We made it pink because that’s what we saw.

Andreas Deja (supervising animator for Lilo): They said, “Hey, Andreas, looks like you’re going to end up animating Lilo. It probably makes the most sense that you go to a local school and watch the kids and see how they behave.” So we did that. We had a tour guide, and he took us in the bus down to a school. He said, “The schools are a little bit protective here. They don’t like mainlanders to come in and snoop. I can’t guarantee that they’ll let you in.” I remember we knocked at the door and a teacher came out. She had a few questions, and I told her and the few kids behind her that yeah, we were from Disney and we’re going to do a movie based on the island. This little girl who just heard Disney, she said, “Did you work on The Little Mermaid?” I said, “Yeah, I drew her father,” and she went, “Yay!” Then they really warmed up to us.

I took a sketchbook with me and drew a little. How fidgety they are in school — girls that age. I got a little bit of that in some of the scenes, when Lilo is talking to the hula teacher about what happened with Pudge the fish.

Sanders: Dean and I were taking a break at this little café and we were just sitting out on the patio. This girl came by and sat down. She was really pissed off. I remember she had a ukulele. I think she had just quit her job, and she was stewing about it. Dean and I had a short conversation with her. She was really the right age and the right attitude. She had kind of an aggressive edge to her. We both realized Nani is that character. Because she has the responsibilities of a parent, we had treated Nani a little bit more grown-up than she should have been. So we took a lesson from that and tried to add that energy to Nani.

DeBlois: There was a lot of careful observation of the folks we met, and trying to channel that regular-life-in-Hawaii feel into the movie so that it didn’t come across as just people in hula skirts standing on a beach, like Blue Hawaii or something like that.

Sanders: Dean and I have no business telling a Hawaiian story. You can tell stories like that, but then you find people who do have a business there. So we reached out to as many people as we could that lived there.

IV. “A great actor, who is right for the role, will change the course of the film.”

Because audio tracks are often recorded before scenes are animated, voice casting often has a huge impact on the ultimate shape of an animated film. As they went about casting and recording the actors for Lilo & Stitch, Sanders and DeBlois witnessed the film transforming before their eyes.

Sanders: We read many, many people for every part, and Tia Carrere was one of the very first people who came in. But because she was literally one of the very first voices, it was very difficult to say yes. You just don’t expect the first voice you hear to be the right one. So we kept reading and reading and reading.

At one point, Calista Flockhart came in to audition for the part of Nani. She looked at the pages and asked, “How old is this girl?” We said, “Well, she’s 19, 20.” She said, “Because she doesn’t seem like she’s 19. She’s acting like a mom.” In her audition, she pushed it younger. A little bit less responsible. More emotional. But the more people we read, the more we just always came back to Tia Carrere. She did a brilliant job acting all the bits. The quality of her voice fit so beautifully with this character.

Tia Carrere (voice of Nani): When I first met with Chris and Dean, they said, “Well, you’re from Hawaii. What do you think about the story?” I said, “Well, how do you feel about Pidgin?” It’s such a particular cadence of speech. All the different ethnicities — Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Hawaiian — all worked on the plantations together, and they couldn’t speak each other’s languages, so they put together Pidgin English, which is made up of broken words and phrases of all the different languages. Chris and Dean said, “How do you want to infuse it into the character?” I said, “Well, I wouldn’t want it to be too strong where the viewer can’t understand. Just a bit of Pidgin, to infuse that character with authenticity.” I was so happy that they were open to that.

Sanders: We met Tia at a restaurant in Pasadena called Twin Palms. Dean and I got there first, and the guy sat us down and said, “Okay, are you ready to order?” We said, “No, we have somebody else joining us,” and he was completely annoyed by that. He went away and we kept waiting and waiting. Then somebody said, “Oh, she’s here.” Dean and I went out to meet her, and it was this limousine. The driver got out and said, “Are you here for Ms. Carrere?” Dean and I said, “Yes!” He said, “Are you ready?” We were like, “Yes?” He opened the door. She was dressed in this amazing, spray-painted-on black leather outfit. I can’t even describe it. The whole place came to a stop. The guy who treated us so badly comes back and goes, “Oh, oh, hello.” I was like, “Yes, our third … our third has arrived.”

It was an amazing dinner because she was so friendly, and so down to earth, and that was when the “Aloha Oe” song came into the film. Tia had read the script. One of our difficult moments was when Nani tells Lilo that they’re going to be separated. We had difficulty trying to come up with the words. It was one of Tia Carrere’s suggestions that she sing Lilo that song. It was a beautiful, honest, very sincere moment.

Carrere: I think Chris asked me, “How would you say good-bye in Hawaiian?” I said, “Well, there’s this, the most famous Hawaiian song, a song of love and farewell written by Queen Liliʻuokalani in the palace, and it’s ‘Aloha Oe.’” They said, “Can you sing for us?” And they’re like, “Oh my gosh, that’s perfect.”

Sanders: When we were in the recording session, she even called her grandmother on the phone to make sure she was getting all the words exactly right.

Carrere: Later, when I did the PR for Lilo & Stitch, we did a TV special in Hawaii. (Kelly Slater was doing some talks on the surfing scenes.) The director said, “Hey, can you sing ‘Aloha Oe’?” I said, “Can my grandma sing harmony with me?” We sat under a banyan tree in Hawaii and she sang the harmony. Much later, on her deathbed in the hospital, it was one of the last things we did. I sang “Aloha Oe” with her, and she was harmonizing with me. My cousin played the ukulele. That’s so deep for me. That song.

Sanders: I believe that characters tend to avoid things. Because I do it in my own life. So when Nani sings “Aloha Oe,” she’s saying goodbye to her sister, but she’s not really facing up to it. That worked beautifully for the film. If it hadn’t been for Tia, who was the right voice, who was Hawaiian, who was perfect for the role, and who helped to bring that into the whole story. A great actor, who is right for the role, will change the course of the film.

Carrere: They asked me other things like, “If somebody almost hits you with the car, what would you say?” I’m like, “Oh, you stupid head.” It’s like such a Hawaii thing. And when I say to Lilo, “Oh, Lilo, you lolo.” These are turns of phrase that we would use in Hawaii when I was growing up.

Jason Scott Lee (voice of David Kawena): Tia brought me into the picture. She was cast first, and so she made the suggestion to let me be a part of it.

Sanders: Once we met Jason, we started hearing all the dialogue in his voice, and that informed and changed everything. Jason could do in just a few words what we were probably overwriting.

Lee: A lot of times, the directors would say, “Oh, just try to do it how you would do it as a local Hawaiian kid.” So I’d do that. They’d go, “Oh, that’s great. We’ll keep this. We’ll keep that.” They liked the cadence — it’s a very specific singsong type of rhythm. We’d take it in less of the Hawaii Pidgin English, and then ease into it a little more, little more, and then maybe do it really hard-core, and then back off. It was that back and forth. I think there’s one line that stands out that was a very kind of a local thing. When they’re talking about Stitch, David says, “You sure it’s a dog?” That’s a very Pidgin English kind of thing. I don’t think they knew that it was going to be read that way, but that’s what they kept.

DeBlois: The most difficult role to cast was Lilo. We auditioned so many girls.

Sanders: We had gone all over the place. We had had searches in Hawaii. We wanted a Hawaiian voice. We couldn’t find one. Kids are hard because, in a sense, you want a kid who’s not an actor. There are lots of actors, and when we would read them, immediately they were overplaying things in a way that sounded false. It was cloying.

DeBlois: It wasn’t until Daveigh Chase walked in with this haunted quality and this really dry demeanor. But then she would explode on-camera when she would do the lines. She could alternate between sort of haunted and glum and over-the-top excited about things.

Sanders: We took the voice that we recorded from that audition, we put it over the character, and we were like, “She’s the one.”

Deja: Daveigh Chase was Lilo. Whether she was like Lilo in real life or not, I don’t know. But she had this sort of matter-of-fact quality. She was living in her own world that made complete sense to her, and why don’t adults understand this, for crying out loud? Lilo withheld a lot of feelings and would communicate through very subtle movements and facial expressions. So even though she seemed like a broad design — like she could be a member of the Charles Schultz Peanuts family with that round head and the big mouth — in the end, she was a character that had a lot of issues and communicated things in her own way.

Carrere: It’s kind of funny that I never met Lilo until the premiere in L.A. She said, “Hi, I’m Daveigh, I’m playing Lilo.” I’m like, Oh my God. She had an adorable little voice. Probably today they would’ve cast a little Hawaiian girl, but there wasn’t that talent pool that they could pull from, because there weren’t that many people in the business and certainly not little kids. She had that sassy little-kid thing. What’s hilarious is she went from Lilo & Stitch to being the scary girl that comes out of the well in The Ring. That was bizarre. I was terrified.

Sanders: We had made the decision to not cast Stitch. He was never intended to speak. He was going to be the equivalent of Dumbo. He would make noises, but he would never verbalize anything. That fell by the wayside almost immediately, and we realized he would have to say a few words here and there.

DeBlois: For the voice of Stitch they kept saying, “Well, no, we’re going to find a real actor that we can use in the promotion.” But, creating the scratch tracks that went along with our story reels, Chris used to do this voice all the time. He would leave me really upsetting voice messages in that voice. I said, “Just do that voice. It’s fine. Eventually we’ll have to go approach someone like Danny DeVito and ask him to make a lot of animalistic grunts and naughty noises.”

Sanders: We thought, Oh my God, we can’t get into a thing where we’ve got a real actor and we’re like, “No, could you just make a bunch of dumb noises?” You just know that suddenly Stitch would be making all these speeches.

DeBlois: But it just never happened. Eventually the pictures married so well with the voice that Chris became the official voice of Stitch.

Sanders: I will say, however, that every time we got audience cards, that was the lowest-rated thing in the film — Stitch’s voice.

McDonald: I’d moved to Los Angeles two or three years earlier, and everyone said, “You have a cartoon voice; you should be in cartoons.” I was in one cartoon, and it made me think cartoons were horrible. It was about a dog or something. The guy who created the cartoon was nice to me — people are nice to Kids in the Hall because we’re like a cult — but he was mean to everyone else. The lead guy, who was, like, a big guy — he probably played football in high school — I saw him crying in the hallway once. So I thought, “Oh, well, I gave cartoons a try. It’s horrible.”

Then I had another horrible experience. Do you remember the Tom Kenny show CatDog? I was going to be … What was he? Dog? I was going to be Cat. But the guy who created it wanted me to do it in a character I did with the Kids in the Hall. The “will do” guy. “Will do, slipped my mind.” That guy. Very low-key. But Nickelodeon wanted me to do it high energy! Maybe Marlon Brando would be able to do low-key with high energy. I’m not Marlon Brando. It was one of the two times in my life when I found out I was fired that I was happy. So I thought cartoons were done. Then they asked me to audition for Lilo & Stitch.

Sanders: Chris Williams was boarding in the film, and Dean and Chris Williams both said, “Oh, Kids in the Hall, Kevin McDonald, that’s Pleakley.” I was not familiar. They said, “We’ll have him come in.” He came in, and suddenly there was the character.

McDonald: Dean was a Canadian. There are so many Canadians in animation. Anyway, he wanted me to do another character that I did in the Kids in the Hall sketch where I play a passive-aggressive guy: “No, no, I’m not saying that. Do you think I said that?” The audition went okay. Then they called me back and I did the same thing. Then they called me back again. I think I had five callbacks. I didn’t find out until a few years after the cartoon premiered that they really fought for me. Disney didn’t know who I was. I had to keep doing callbacks not so much to prove it to them, but to wear them down. That was really the beginning of it for me. Now I’ve done 10 million cartoons.

Sanders: You write enough to frame up a character, but the frame is empty. And then somebody like Kevin McDonald is suddenly in the frame, and now everything’s going to change.

McDonald: I know my instincts are always just to go for the comedy. It was definitely a comedic character, but I probably pushed it more that way. Because it’s impossible to do anything else with me. Not that I’m so good at comedy, but all I am is comedy.

I think they were going for a Laurel and Hardy thing with Pleakley and Jumba. We were definitely the comedy stooges. Of course, David Ogden Stiers got the more dramatic stuff to do. We became friends, I really loved him, and I learned very early not to mention M*A*S*H. The funniest thing he ever said to me was, “I was in five Woodys, you know.” It was the oddest friendship ever.

I actually didn’t meet him until the premiere! They brought us to Florida for a week and that’s when I met him and got friendly with him and stayed in touch with him. And then we did the TV show together. They were nice to us; they’d always have one of us finish when the other one was starting, so we’d always say hi to each other.

Sanders: The social worker, Cobra Bubbles, started out as you would expect: this nebbish, skinny little guy, very by the book. He could have been a librarian or worked at the DMV. We actually approached Jeff Goldblum at one point for the voice. It was great to meet him, and he was such a character, but he eventually declined it. That was a moment where we went away and said, “Is this really the character that we want? Is he interesting enough?” So we had the idea of just going the opposite direction.

DeBlois: We thought, No, he’s got to be intimidating. He really has to put the fear of God into them. And at the time, Ving Rhames and the character that he played in Pulp Fiction were such a high bar of intimidation. We just had the audacity to approach him.

Sanders: The first time we met Ving Rhames, we recorded him in Vegas and he was doing a boxing movie, I think. We were both really nervous to meet him. The door opened to the studio, he came in, and we were like, “Oh, hello Mr. Rhames,” and he shook our hands and just walked past, went directly into the booth, put the headset on, and looked up. Both Dean and I were like, “Oh, okay,” and we ran to get into position. Then at one point, he stopped and he said, “Who wrote this?” Dean and I are both like, “Oh, well, he did.” We actually pointed to each other. There was a pause, and he goes, “Because it’s good. I like it.” He was no-nonsense, and worked like crazy, and was so good.

DeBlois: He would do the line and then he would look at you with this impatient glare, and we were just scrambling over ourselves to give him direction. He would direct the line at you. So he would be speaking to the microphone, but he would be bearing down with that furrowed brow and that deep voice, that massive physique, staring at you.

V. “You don’t mess with hula.”

As in almost all Disney movies, music would play a hugely important role in Lilo & Stitch. With this film, however, there were additional challenges associated with creating a soundtrack that could organically switch between Elvis songs, traditional Hawiian music, and an orchestral score. Furthermore, hula was a key element in the film, and the filmmakers knew that it was part of a far more complex world than had been featured on film and TV in the past.

Sanders: You don’t mess with hula. You know, some people treat hula as this sort of silly thing. Gilligan’s Island. They’ll dress up in hula skirts and do some sort of mockery of the hula — that’s how Hollywood has treated it. What we learned very quickly from everybody we were consulting with is you don’t do that.

Carrere: Well, it’s a storytelling device, and there are certain schools of hula from different kumus, the teachers that handed it down. It’s very much a special and very particular art form.

DeBlois: To Chris and I, music is half of the equation. It does all the heavy lifting emotionally. So we said, “Whatever budget you give us, we know it will be less than the typical feature at Disney, but make sure that we get a top-notch composer.” Top of our list was Alan Silvestri. Alan is so curious that he started scouring everything he could find on traditional Hawaiian music.

Alan Silvestri (composer): We wanted to bring in this more traditional Hawaiian influence to some of the songs, and we discovered there is a very deep, sacred aspect to real traditional Hawaiian music. It’s a very cared-for tradition from Hawaii.

Sanders: I went to Virgin Megastore looking for music, and you could find, like, two CDs of Hawaiian music. The African-music section was huge, tons of CDs, but like two in the Hawaiian part. We found out that’s because the parameters are very clear as to what you can and can’t do with this music. We wanted to orchestrate this music. We wanted to take these Hawaiian themes and make them movie scale. And that’s a bit of a no-no.

DeBlois: Then Alan stumbled upon a guy named Mark Keali‘i Ho‘omalu, who was a kumu hula — a hula master who was living in the Bay Area. It was just a strip mall in this old sort of karate studio next to a donut shop that he’d turned into a hula studio.

Silvestri: He had a storefront in some shopping area, like many churches do now. That’s where his students would congregate, meet and do their work together. We sat there, and Mark was a real force. He was a very powerful man.

DeBlois: Mark was considered to be a bit of a rebel because he would take these old chants, and his versions of them just had a lot of melody and harmony and breaks in tradition that were, I think, considered sacrilege by some purists. But to others, he was bringing old Hawaiian music to a new generation. Alan recorded him singing these revered ancient Hawaiian chants, but set to music in such a way that it brought this amazing breadth and scope and very cinematic quality to the music.

Silvestri: It was a very interesting courtship because Mark was very guarded, as he should have been. He didn’t want a bunch of commercial knuckleheads walking on the sacred ground with their nonsense. He was protective. It took us a while to win him over.

Lee: The Hawaiian community is very sensitive about outsiders coming in and protecting their culture.

Spencer: We needed a children’s choir to sing in the opening song. We went to record with the Kamehameha School. So we fly to Hawaii, we’re in Honolulu. We have not heard the kids sing. We know they’ve been practicing.

Lynell Bright (music teacher at Kamehameha Schools): We learned one song, “He Mele No Lilo.” We were supposed to record it in May, and then it got pushed back to October. Then, after September 11th, it got pushed back to December. By then they decided to do a second song, “Hawaiian Rollercoaster Ride.”

Sanders: We go up to the school, we hear the kids sing in their environment, and Lynell Bright, the choir director, is playing the piano. You just got so emotional. And you can’t imagine that it would get more emotional, but it does. We go to record them, and there’s no huge recording studio in Honolulu. We’re in a very tight space where only the kids can fit. So all the parents are outside the studio. We said, “After we’re done recording, we can bring the parents in groups of 15 or 20 to hear what has been recorded.” So they come in, and … everyone was crying. Every 15 or 20 people who came in — crying. Because there was this feeling that they were a part of the movie and their child’s voice was going to be in this for history, for all time. That was really phenomenal to watch. We just take for granted some of those things.

Bright: I think Mark Ho’omalu’s nephew was in the choir. And he came to a concert at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, where we sang. So I think he brought up the idea. Back then, we used to always sing a Disney medley. Whatever the latest Disney movie was, that would be one of the songs we’d perform. That particular year, I’m pretty sure the Disney release was Dinosaur. We were like, Oh, there’s no music in this movie! Then I got a phone call. “Hey, Disney’s going do a movie. Would you want to be a part of this?” I’m just like, “What? That’s a dream come true!”

John Sanford (artistic supervisor for story): Chris always was a huge Elvis fan. The fact that he folded the Elvis music into the movie … it was one of those things that he would always talk about.

DeBlois: We actually didn’t think that we would (a) ever be able to license the music or (b) be able to depict Elvis in the movie. We figured at some point someone was going to pull us aside and say, “You can’t do that.” But representatives of the Elvis estate came out to look at our story reels, and they got behind it. So strangely we found ourselves having a premiere at Graceland. We got a special tour of the vault at Graceland where we took a look at these crazy rhinestone jumpsuits. But I pointed at one box and I said, “What’s that?” Because it said “Toiletries.” And the guide said, “Oh, these were the toiletries that were in the bathroom where Elvis was found.” And there was a bottle of Hai Karate cologne.

Schumacher: Were you old enough to know what Hai Karate was? Hai Karate was an aftershave that everyone’s gym teacher wore after they gave up Old Spice. I said, “Can I smell it?” She goes, “You can sniff it, not spray it.” So I take it — it’s half-filled — and we all sniff it. It smelled just like our PE teachers. It was Hai Karate. They would sell it, Hai Karate, with a white guy in a gi. Oh my God. Anyway, people my age were raised with a lot of influences that aren’t really great.

VI. “Nobody’s done this since the 1940s.”

Early on in the development of Lilo & Stitch, art director Ric Sluiter suggested to Sanders and DeBlois that they consider using watercolors for the film’s backgrounds. Sluiter had previously art directed a Roger Rabbit short, Trail Mix-Up, and had used acrylic paint to emulate a watercolor style in that film. Real watercolors, however, hadn’t been used in a Disney feature in nearly 60 years, and much of the craft and knowledge around the form had been lost in the intervening decades.

Sanders: Ric Sluiter took one look at the stuff we were drawing and said, “The perfect complement to your rounded character style would be the watercolor backgrounds that Disney studios did routinely back in the 1930s.” Dean and I both said, “Yes, let’s do that!” What I found out later is that Ric Sluiter greatly regretted having said that! Ric went back to his hotel room that night and produced a couple of paintings. One of them was watercolor and one of them was done with opaque gouache — The Lion King, Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, all of these are gouaches. Ric came back and said, “Here’s the thing: Watercolor is going to be really difficult. Nobody’s done this since the 1940s. Nobody even knows what kind of pigments or kind of papers — all those things are gone. They would have to be rediscovered. Also, you have to be like a painting ninja to handle watercolor.”

DeBlois: It’s a very unforgiving medium because you can’t really cover over your mistakes. You’re using the white of the paper as the light source in your image and you’re slowly applying these transparent washes of color to bring to life the image. If you make a mistake on a watercolor painting, it’s ruined. You have to go back to the beginning.

Sanders: When Ric showed us the two paintings and said, “This one is watercolor and this one is gouache made to look like watercolor” — and Ric worked really hard; that gouache was as close to watercolor as he could make it — both Dean and I took one look at it and said, “Nope, we want the watercolor.”

DeBlois: That whole team of artists in Florida in the background department were such avid painters. They went back and did research and experimented with pigment, types of watercolor, paper. I think they were really excited about the challenge.

Sluiter: We took seven months and we had watercolor workshops and we went out and painted almost every day outdoors. There were maybe eight, nine background artists, and there was only one who knew watercolor: Peter Moehrle. I have to give him a lot of credit there. He taught me a lot.

Sanders: On one of my visits to California from Florida, I ran into a senior member of the background department and he said, “I heard you’re going to do watercolors. When you guys get into trouble, because you’re not going to be able to pull it off, I’m not so sure California is going to be able to come to your rescue.” That really pissed me off.

Ron Betta (assistant production manager): I saw the frustration on the watercolor team that was trying to figure out how to get the paper stretched and how to get the watercolor down on this paper without having it rumple up, because when water gets onto the paper it’s going to cause it to flex.

Deja: That background-artists group actually flew back to California, and then they met with one of the guys who painted backgrounds on Snow White, who was still alive.

Sluiter: Maurice Noble was one of my heroes, and he was in his 80s. He used to work for Disney in the ’40s and ’50s. He could hardly see. One great technique that he told me about: There were these rocks in Peter Pan, in the Mermaid Cove, with beautiful rock texture. I asked, “How’d you get this texture?” He said, “The secret is sea salt — very coarse-grain sea salt.” Now, I had tried to get that texture so many times, and I knew about the salt technique, but I never knew you used sea salt. So all the lava rocks in Lilo & Stitch — it was all sea salt. It came right from Maurice Noble.

Sanders: In the end, the Florida artists became so facile with this watercolor thing that they were producing backgrounds faster than they had ever produced gouache backgrounds!

DeBlois: Really, for Chris and I, our jobs walking into the background department were just to comment on whether or not it was addressing the story concern of the scene. As long as it was representing what we were trying to get across emotionally and in terms of the continuity, we were happy to just let them go and let them be artists.

Sluiter: I remember Chris Sanders, when he saw the first watercolor backgrounds coming through, he was so excited. He was just sitting there staring at this painting of the foliage, and he said, “It’s like therapy.”

DeBlois: You can see all the telltale signs of an artist’s hand moving across the picture planes. It complemented the entire mission statement of making the movie: Let’s embrace our B-movie budget and just let it be the style that it aims to be.

VII. “We didn’t want to let anybody down. We had things to prove.”

Lilo & Stitch was based primarily on one artist’s aesthetic sensibilities. That made it unique among Disney productions; it meant that the characters didn’t look like typical skinny-waisted princesses. And despite the fact that the staff at the Florida studio was relatively small, DeBlois and Sanders were determined to not micromanage their animators.

Deja: Usually you come onto a movie and you’re assigned to a character and you are responsible for the design first. Then you do some test animation and you work with other animators to make sure these characters belong in the same world, and one person or the other has to make adjustments. This was different. It was all Chris’s aesthetic sense.

Sanders: I was thinking, Well, I don’t know why I draw like I draw; I don’t even see myself having a style. So we turned to an artist in the studio named Sue Nichols, and she took my drawings and she went away for a few weeks and she did an analysis of how I draw. She came back with a multipage book called Surfing the Sanders Style that explained why I draw like I draw. No one was more interested to read this than I was! This book became a primer for anybody who was coming onto the film.

Coats: I remember Chris Sanders, when he was drawing Nani, he asked our production supervisor to pose for him. “Can you pose because I want to draw your legs on Nani?” Chris just went there, as opposed to having to have conversations about, Hey, can you make a woman look like real women? Everyone struggled with that. Women had to have this unrealistic body type.

Sanford: This is going to come across like me knocking California, but I have to speak the truth. If you’d brought Lilo & Stitch to that crew, and you gave Stitch to one of the supervising animators, they’d say, “Well, I have to redesign Stitch because I have to put my stamp on it.” The same thing would have happened to Nani, and the movie would look like every other Disney movie. But with the Florida studio, they were like, “Oh, we get to do a movie that looks like Christmas drawings.”

Betta: We had things to prove. We were always compared to the other studio. We were seen as the not-so-cool younger brother. Florida yokels versus the elite Hollywood movie-star kind of group.

DeBlois: When we arrived in Florida, we knew these people because we had worked on Mulan with them. That was a difficult film to finish. There were lots of divorces and ailments that came out of that process. I remember myself working daily until well past 11 p.m., listening to people riding the Tower of Terror and poor custodians pushing around vacuum cleaners in these trailer buildings. So we made a decision. We sat down with the entire crew when we got there. We said, “Okay, here’s the deal. We have a lot less money. We have less time. But we want to figure out how we can make this movie so that everybody goes home at night to have dinner with their loved ones. Everybody gets a weekend. We’ll figure out how to make this and be happy doing it.” That became the spirit of making the film. There were all sorts of barbecues and kayaking in Florida Springs and taking little road trips down to the Keys or out to the coast. Ric Sluiter would take us out on weekends and we would go scalloping or shrimping late at night. Dropping lights into the water and catching shrimp.

Sluiter: Mulan was five years of hell. Lilo & Stitch was two years of bliss. Everything went so smooth. Because Chris and Dean were writing the movie and storyboarding — they did the whole movie themselves, an incredible feat. So basically once they knew that the style was there, they just left me alone. They did all the approvals, everything, but they left it to me so they could focus on stories.

Sanders: Dean and I found our comfort zone in not telling animators what to do. These are our actors, and, of course, if you’re in animation, you have your actor actors, and you have your animators who are also actors. And we made the decision early on that if they check all the boxes that a moment or scene needs, then we are done. We’re not going to get into a thing where, “I kind of saw it more like this.” Now you’re in a situation where some poor animator is like, “So you want him to do what?” They’re suddenly like somebody taking an order instead of doing what they do best.

IIX. “What if we made our villain the hero?”

Lilo & Stitch didn’t have the kind of large story team that would have been common on a Disney production. Very often, major story alterations could happen relatively quickly with input from just one or two people. That resulted in a smoother production process — save for one enormous, shocking, last-minute change that came after the film had all but wrapped.

Sanders: When we were working on Mulan, there came a day when we were talking, as we quite often did, “How are we going to kill the villain?” It’s kind of funny to think how many times in the halls of Disney you would sit around talking about “How are we going to kill the villain?” “Oh, what if he blew up in a fireworks stand?” That led me to think, What if we actually redeemed a villain? What if we made our villain the hero? Really, if you take everything away from Lilo & Stitch, that’s what the story is. It’s a redemption story where the villain and hero are the very same character.

Sanford: The thing that impressed me about how Chris was developing the story is that it developed really organically. I always describe it as a spiral. He’s telling the story about this alien. Then this alien meets this little girl. Okay, well, this little girl needs a family, so there’s a big sister. These characters just develop, and then somebody is chasing him. Where did this alien come from? Well, there’s this Galactic Federation. Then all those characters start filling in.

DeBlois: There’s a strange, magical moment where once you’ve worked on it for long enough, the movie starts to tell you what it wants. It will reject things that feel unnecessary or forced upon it. But it will also ask for those moments that it needs. It just became clear in watching it over and over again that the balances had to be shifted constantly until we found that dance between sincerity and ridiculousness.

Poole: I think Chris and Dean were a good balance for each other. Chris would have these wild ideas about this could happen and this could happen and this could happen, and it felt sometimes like Dean was the one who helped figure out the connective tissue.

Sanders: Roy Disney prompted one of the biggest changes in the film. At one meeting, he said, “I liked Stitch when I thought he was a baby. But when I realized he was a grown-up that was in charge of this whole gang of aliens, I didn’t like him as much.” I thought, Okay, this is too large a note; we have to deal with this right now. I said, “Okay, if we made it just Stitch, maybe they move him around in a jar and people or aliens in hazmat suits handle him. It’s almost like he’s a virus.” The room got really quiet. I looked over at Tom, and Tom was looking at me and he didn’t look away. I said, “The equivalent of a virus would be a genetic mutation. If Stitch was a genetic mutation, then he can be the problem by himself. We can eliminate all these other characters.” So we went into the meeting and there was a whole gang of aliens, and we left the meeting and there were no more aliens. All these people didn’t know, but their parts were cut.

By that point, we had already recorded Ricardo Montalbán as one of the bad guys. Oops, sorry. He was really nice, and I’d persuaded him to do his voice from Wrath of Khan. During the recording session, I kept saying, “Well, could you do it maybe a little bit like this, or a little bit more like that?” I didn’t want to just come out and say it. He kept doing all these different voices and was working so hard. I finally basically said, “Can you just do the voice you did in Wrath of Khan?” He was like, “Oh, YOU MEAN LIKE THIS?” And he did it! And then — this is why I never want to be a producer — the producer had to make the phone call and say, “Unfortunately, we took your character out of the film.”

Sanford: Early on, Chris and I drove down to Laguna Beach. He had a Sharpie and a story pad and we had wings and beer, and we talked about the story. He really was adamant that Stitch did not have to go back to space. He wanted Stitch to find a home with his little girl and her sister. He said, “I can’t figure out how to justify that they stay. The grand councilwoman is going to take him back.” I said, “Wait a minute. When Lilo adopted Stitch, she had to pay money, right?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, she’s got a receipt. If the grand councilwoman takes him away, that’s stealing.” So that’s where that scene at the end came from, where Lilo just holds up the receipt.

Sanders: We had an internal screening in California. Sometimes big, giant, obvious things, you miss them because you’re so busy attending to other things. I said aloud, “Stitch goes from bad to good, but we don’t have any reason that he changes from bad to good.” Then we realized, “Oh, Ohana has to be the thing that changes him.” So we started putting it into the film much more overtly.

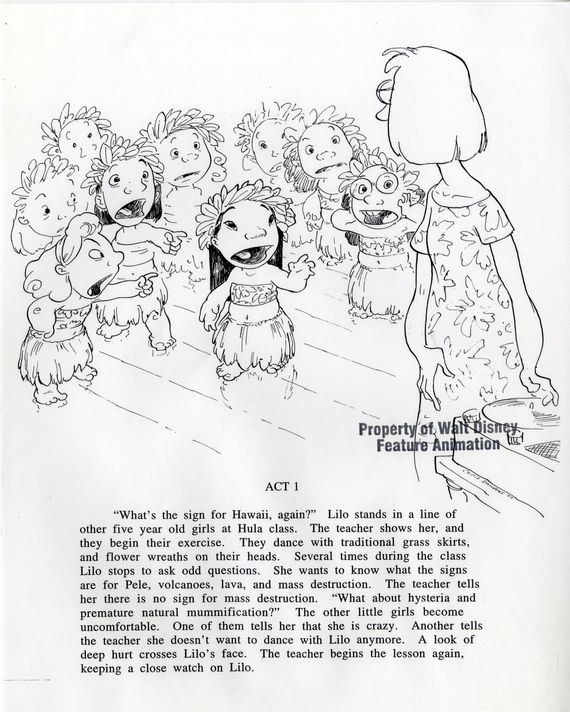

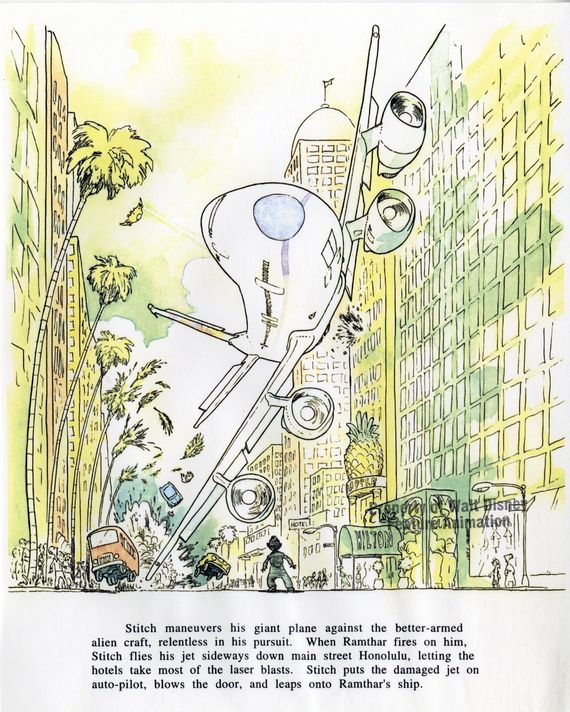

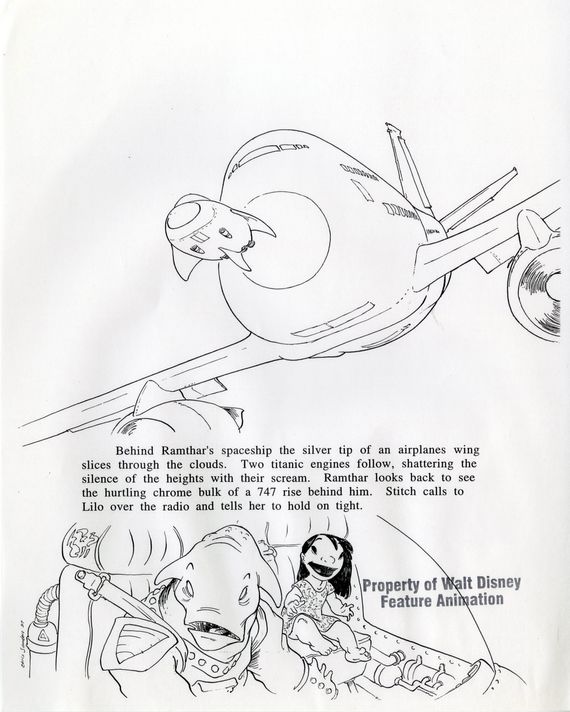

DeBlois: At the end of the film, originally, Stitch grew a conscience and realized that he needed to go after Lilo after she’d been napped by Captain Gantu and was being carried off in his ship. Stitch was still dangerously irresponsible. He ends up stealing a 747 from the airport and flying it in a chase with Captain Gantu through downtown Honolulu. The landing gear comes out and they’re careening off of buildings, and glass is shattering and raining down on the streets. It was finished and in color. And then 9/11 happened.

Schumacher: I was bicoastal in those days. A lot of Disney people were in New York because Monday, the tenth of September, was the memorial service for our then–head of labor for theatrical, a really lovely man. Everyone was going to fly home on Tuesday. And then 9/11 happens. Twenty people end up in my tiny apartment on Central Park South. Then my phone rings, and it’s Chris saying, “Tom, what are we going to do?” I said, “Chris, well, it’s rocky, but I’m going to try to get everyone home.” And he said, “No, no. What are we going to do with the final chase in the movie?” I’m like, “Holy crap!” This scene went from being funny and outrageous to horrible and tragic and traumatizing. I think the next day he called me and said, “Here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to wrap the 747. They’re going to take Jumba’s ship.” They just reskinned everything.

DeBlois: We kept the sequence, but then downtown Honolulu skyscrapers became mountain canyons. And the stolen 747 became the ship Jumba had originally arrived in. We kept the pacing of the sequence more or less the same, but we had to change a lot of the obvious references.

Sanders: Poor guy with the ice-cream cone was going to be crossing the street in Honolulu. Now he’s in Kauai on the beach and gets his thing knocked off.

IX. “Oh my God, we made a film and we never told Michael Eisner.”

Lilo & Stitch had been produced quietly and for relatively little money in Florida. But eventually, Disney leadership — not to mention the public — would need to see it. The world of animation had changed dramatically over the years. Pixar’s first feature, Toy Story, had been a huge hit in 1995, and by the time Lilo & Stitch opened in 2002, computer-generated animation had become dominant (with A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2, and Monsters, Inc. all debuting in the intervening years). That made Lilo & Stitch a throwback of sorts. And yet it was also thoroughly new. For all its offbeat qualities, Lilo & Stitch was prophetic: It probably has more in common storywise with later Disney hits like Frozen, Moana, and Encanto, which also foreground a female protagonist without a marriage plot. And it would prove to be a hit. While its box office wouldn’t come close to Disney Renaissance classics like Aladdin or The Lion King (Lilo & Stitch made $273 million worldwide, while The Lion King made $1.06 billion after multiple re-releases), it did good business compared to costly behemoths like The Emperor’s New Groove ($169 million) and Atlantis: The Lost Empire ($186 million). It would also inspire three direct-to-video sequels as well as several TV series and video games.

Sanders: Michael Eisner didn’t see it until it was done. Michael Eisner saw it when it was in color, it had music, it was pretty much completely finished. Everybody was nervous, like, Oh my God, we made a film and we never told Michael Eisner. So we came out of the screening and Michael Eisner was standing there, and he’s so tall, and he said, “Chris, Dean. I really liked this. I like it. I can’t really explain it. I’ve never seen anything like it … but I like it. It’s just so hard to explain … but I really like it.”

Schumacher: By the time the movie came out, there was a lot of frustration that it wasn’t CG. The marketing people asked, “Well, how do we release this movie? It’s not CG.” There was even a suggestion by a very important player that we do the commercial in CG. I said, “That seems a little dishonest.” The movie works because it’s not CG. You can show me a leaf from Pocahontas, Hercules, Mulan, Lilo & Stitch — a leaf — and I’ll tell you what movie it came from. Because if it was from Hercules, it has a Gerald Scarfe spin on it. If it’s Pocahontas, it has a seam going up, and there’s one color here, one color there. Lilo is going to be watercolor. They all look different. There’s a sameness you can get into unless people really push the boundaries. Having worked in both, this film was such a celebration of hand-drawn animation.

I kept being told by the publicists, “Nobody cares about the watercolors.” I said, “We’re going to teach them what it is.” We went to the Cannes Film Festival to promote it. Clark, Dean, Chris, me. Roy and Patty flew us there on Air Roy, a private 737 they owned. I think we put 500 journalists through a class where they got to learn how to watercolor paint. They all got a kit with exactly the four colors of paint you needed, rock salt, and you had to float your paint on the wet paper. It was amazing.

Carrere: I just thought, “This is so beautiful.” The paintings of these places in Hawaii feel like actual specific places, not a broad-stroke rendering of some nondescript tropical island, you know? The houses are like the houses that I grew up around. Nani looks like what a local girl would look like, with the sturdiness of her legs and her body. She’s not like Cinderella painted brown. I love that Chris and Dean were cognizant of what they were putting in front of the world. It was so ahead of its time on so many levels. The social services, the older sibling taking care of the younger sibling and the chaos and mayhem that ensues, that this family is sort of this odd cast of characters that you cobble together and that have each other’s back. I think that’s a thoroughly modern theme. To think that we did that 20 years ago is kind of amazing. Also, to have the Indigenous story, the local people’s story front and center in Hawaii, whereas usually Hawaii would be the fetishized beautiful backdrop for Caucasian lead characters. On so many levels, I was so proud to be able to represent Hawaii.

McDonald: I’ll tell you the truth. It was better than I thought it was going to be. There are two cartoons that I’m asked about all the time: Lilo & Stitch and Invader Zim. Invader Zim are the people who were young and grew up to be Kids in the Hall fans. Lilo & Stitch fans are usually from a different world. Usually it’s a family. The parents are in their 40s or early 50s, and they have a 26-year-old daughter who’s really shy because I’m Pleakley. I’ve met 100 families like that. It’ll probably be the thing they say when I die. It won’t be Kids in the Hall, it’ll be “Voice actor from Lilo & Stitch.” For my personal taste, being a Kid in the Hall with a dark sense of humor, I give it … two and a half stars. [Laughs.] Oh God, I hope Dean doesn’t read this. But no, I definitely like it! It’s good, it’s good! Still, two and a half stars.

Bright: In any culture, if there’s a movie that’s done about the culture and with the culture, they’re going to be very careful and critical. I think people in Hawaii were excited that Disney was doing something about Hawaii. But anytime, there’s going to be positive and negative. So I think there were some mixed reactions.

Lee: I was pleasantly surprised. In taking a fantasy and applying it to a blue-collar worker, and really depicting the socioeconomic situation in the lives of many local people here. The whole thing about the older sister raising the younger sister — that’s real. I mean, those stories still hold up. You don’t often see Disney animations like that.

Betta: I go to Disney all the time. Little girls will walk around in Lilo costumes. I walk right up to the parents. I say, “I worked on that film. Thank you very much for allowing your daughter to get dressed up like Lilo.” Because it is so beautiful to me to see that 20 years later, kids are still wearing it.

Deja: I love it. And that’s not always the case. I don’t always love the final version, because the final version is when you’re sitting there and saying, “Well, this is what it is.” You can’t go back in and say, “Can I have sequence 13, scene four back?” I just loved it. Just like the whole audience, I laughed and cried and got really involved. I thought, This is one of our best ones. I insist that had Lilo & Stitch come out right after Lion King, it would’ve made twice as much business. I know it, because we were riding so high and then we did a few movies after Lion King that didn’t connect with audiences as well. So animation took a little bit of a downturn. Lilo & Stitch brought it back up again.

Sanders: We were in the right place at the right time. Tom Schumacher was there to protect this film. So many people were in the right place at the right time who helped us out in Hawaii. I just imagine how many times this could have gone wrong. It almost makes me freak out now, just thinking about how many near misses this thing probably had. It was like bowling a strike. You’re like, “It’s going to make it, it’s going to make it,” and you hit that, and that may never happen again.

Schumacher: The two movies that I get asked about more than anything else are Emperor’s New Groove and Lilo & Stitch. Those two movies, in their own moment, people were like, “What are they doing?” I don’t think anything I ever worked on was more painful than Emperor’s New Groove. I felt a lot of guilt about that movie for a very long time because people within the company were so abusive about it. But Lilo & Stitch lives in the hearts of many, many people.

Don’t lose sight of what this movie is actually saying. That here are these two young women, who are on their own through tragedy, and they build a family, right? This film is so much about kindness and embracing the other. I cannot watch the movie without tearing up. When Stitch goes outside and says, “I’m lost.” How does anybody watch that and not tear up? And her unconditional love for him. The sacrifice, patience, the trying to understand another’s thinking? How does he see it? They do that and that they build this family, and Pleakley and Jumba come in their own way to be part of this family. This is their family — it’s broken, but it’s their family. The idea of kids watching something about a family that’s busted up and broken, but knowing that if they care about each other, they can build a path forward.

Bright: One of the kids in the choir said it the best recently. He said, “When we were kids, we thought it was a great Disney movie. Here’s this alien, and it’s just a fun movie.” But now that he’s an adult and he looks back at it, he said, he sees that message about family. It doesn’t matter what size you are or how different it is, a family is special. Now he’s an adult and he looks at it a different way.

Sanders: At the very, very end, I was sitting at my desk and Tom Schumacher called, and he said, “Chris, if you had an extra minute, what would you do on this film?” I said, “Well, I would do a postscript to the film. I would show their life after the film ends.” He said, “You guys have been so on budget, you have a couple of million dollars left over. Do that ending.” We added those two minutes, and I think it totally changed the film.

Schumacher: I think that whole celebration at the end of the movie, when you see them all together, with the photographs and stuff, and you see them skiing and everything. I think it just says, “We can all make our own families.” For those of us who have had to do that, I think its legacy is: It’s beautiful. I think for the industry to see what these artists could do is extraordinary, and I think its actual themes are as valuable or more valuable today than they’ve ever been.

Sanders: One of my co-workers gave me probably the greatest compliment. He said, “Lilo & Stitch is the closest thing to a Miyazaki film Disney Studios will ever make.” Because it really has that quirky, individual kind of a signature on it that cannot survive the normal process that these things go through. We were able to do that because, first, Tom Schumacher was willing to take the risk of letting me lead this film. And then he took the risk of hiding it from the studio at large.

CODA: “That beautiful dream was over in a heartbeat.”

The success of Lilo & Stitch in 2002 was one of the Florida studio’s triumphs. But it proved to be short-lived. Disney was already starting to move away from hand-drawn animation by the time Brother Bear, also produced at the Florida studio, opened in 2003. Roy Disney, long considered a champion of the animation department, had left that November amid a power struggle with Eisner. After a series of canceled projects, salary cuts, and layoffs, the company finally closed the Florida studio in January 2004, firing more than 250 animators, technicians, and others in the process. In a statement at the time, David Stainton stated, “Having the entire animation group working together in Burbank under one roof will further enhance our filmmaking process” — which surely rang as ironic to anybody who had witnessed Lilo & Stitch’s successful production away from the eyes of Burbank.

Sluiter: We were completely blindsided. I remember the day it happened. They said that David Stainton and Pam Coates are flying in. It was a Friday. I said, “They are? Oh, that’s not good.” Kevin the PA, he was getting the ice-cream cart because usually when they came for a meeting they’d have ice cream. He said, “No. They’re just coming to have ice cream with the crew.” I said, “No, bad news comes on a Friday. I don’t know what it is, but it’s bad news.” We were working on A Few Good Ghosts. This movie went through so many changes — it was called My Peoples, A Few Good Ghosts, Angel and Her No Good Sister. Dolly Parton was starring in it.

Coats: I loved that studio. When we made the decision to shut the studio down, I said, “No, I’m getting on a plane. These are my people.” I was the executive who had spent the most time in that studio. I’d flown out there initially and did Trail Mix-Up and then Mulan. I loved those people. I knew them by name. It was crazy hard because you knew their families. You had been at barbecues with their families. They weren’t numbers on a piece of paper that says, “Hey, we’ve expanded too quickly.” So I felt I had to stand in front of those people.

Sluiter: That was probably the saddest day in my life. Workwise for sure. People fainted and they fell to the ground on their knees crying. Grown men crying. It was bad. That beautiful dream was over in a heartbeat. It was gone. It was horrific. People got shingles, people got insomnia. Everybody got sick afterward, physically sick. You have to deal with this loss, and then you’ve got to find the next gig. It happens so much in the movie industry.

Schumacher: I was in Florida a couple years ago, right before the pandemic broke out. I was casting Aladdin in Mexico, the play. I said, “Can I go see the old animation studio?” It just made me want to vomit, I was so heartbroken.

Sluiter: As the years went on and I worked for other studios, I realized there wasn’t a better working environment than what we had there. We were all young kids when we started. We all grew up together, like a family. There wasn’t this hierarchy of the upper layer, the middle layer, and then the guys at the bottom shoveling coal into the Titanic. There was this collaboration that went from top to bottom. We were just this little studio out here trying to hang on to the apron strings of what was going in California.

Sanders: As far as traditional animation, Florida was where it was at.

Sluiter: It’s gone. It is gone. Will it come back? I don’t know. I watched Klaus, by Sergio Pablos. Beautiful. All those Sleeping Beauty lines. But I don’t know. It might be gone. It just takes so long to get to that level of expertise. Most animators go through this same thing: You first get the character and you’re just drawing the scenes. Then you’re on the movie for a year, year and a half, two years. By the end, it’s like you’re living the character. They all want to go back to the early scenes and fix them and change them because they’ve gotten so good at understanding the character and how they move and the line work and the posing and the gestures. You get to such a certain skill level when you’re doing it, film after film after film, that you just keep improving. It’s not like you can grab a bunch of 2-D animators who haven’t been drawing for ten years, or five years, and throw them on a movie. It takes time to get to that level. Unless they can put together a studio, you’re not going to get that level again. So as far as the hand-drawn stuff goes, yeah. I don’t know, man. Might be gone for features.

I actually have a hard time watching animation now because I see the same expressions, gestures, hand movements, everything. Everybody just uses the same stuff over and over again. It’s this formula of animation. I don’t see the uniqueness anymore. I look at live-action movies and you’ve got an actor, right? And the actor can change his persona. He can change his character. He can laugh a certain way in one scene, he can put on an accent in another. He can walk a different style. A good actor will change himself. But in animation, they seem to just grab a formulaic impression and plug it in. It’s a plug-and-play thing. You know that saying, “Death by mass destruction”? I used to say, “Life by math destruction.” You’ve got to kill the math. If you can see the Bayesian curve, if you can feel the timing — that’s math. You have to kill the math to make it feel alive.