This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In Japanese, “Kaizen” roughly translates to “change” (Kai), and “to become good” (Zen), or, more simply put, “change for the better.”

It’s a crisp sunny day on Myrtle Avenue in Irvington, New Jersey. Summer is slowly winding down, and school starts in a few weeks. Like most summer days on the block, folks chill on their porches, enjoying the sun and the latest neighborhood gossip. The birds chirp harmoniously like Bone Thugs. All seems right with the world. Then, a loud gunshot. Another shot. Another. Screams ring out across the neighborhood. People run for their lives, panicking. A man with dreadlocks in his late 30s, dressed in body armor and carrying a high-powered rifle, casually strolls down the block. Moments earlier, he fatally shoots a father of two in the neck, and he intends to kill more. The man aims his rifle at a neighbor of almost 30 years, calmly pulling the trigger. She narrowly evades death. He walks a couple more feet before reaching our childhood home — a home his grandfather owned. He walks through a side corridor connected to the back of the house and patiently reloads his rifle. Sirens blare as cops close in.

After today, the man will be called a murderer, a mass shooter, and a domestic terrorist. However, back when we met him in the 1980s, he was just Kaizen Crossen. We called him “cousin,” but he was more like a big brother to us.

We first met Kaizen when we all lived in a notorious housing project in Newark named the Garden Spires — two high-rise brick buildings built in the 1960s. Oddly enough, there were no gardens in the ghetto. Just concrete, rats, and shitty elevators. It was erected two years before the Newark Rebellion, one of many race rebellions throughout the U.S. in 1967, during President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. LBJ was hoping to combat indigence by providing affordable housing to the working poor.

At first, things looked promising. Our grandmother, Ann Crowder, and her abusive ex-husband, Willie, moved to Newark from High Point, North Carolina, toward the end of the second great migration in 1970, when more than 5 million black people from the South moved north and west. Initially, they lived on South 14th Street in the notorious Central Ward, but in the early ’80s, they moved to the Spires. Willie, who eventually went to prison for murdering his girlfriend at church, worked as a maintenance man for the housing project. By the time we were born in 1985, crack had decimated the city, and the Spires transformed into a hotbed for criminality. Dealers sold drugs wholesale on some floors. In his book United, Senator Cory Booker, the former mayor of Newark, wrote that the Spires “functioned as a drive-through: People didn’t even have to get out of their cars to buy drugs. The dealers catered to them with a speed and efficiency that would have made McDonald’s jealous.” Eventually, things got so bad that Booker staged his now-infamous ten-day hunger strike to raise awareness and win political points against longtime mayor Sharpe James, whom he battled in an epic street fight for the mayorship of Newark.

Unfortunately, some members of our family contributed to the decline of the Spires and Newark. For instance, our dad helped facilitate the drug trade by acting as an enforcer for a prominent gang in the city. From 1985 until 1991, he and his crew fought for territory in the Spires, while the U.S. government waged a vicious war on drugs. Many people died during this war. Eventually, our dad got arrested for a litany of gang-related crimes, leaving us to fend for ourselves in the concrete jungle.

It was in this precarious environment that we bonded with Kaizen, a fellow bastard of Newark. Kaizen’s mom was addicted to drugs, and his father bailed when he was a baby. Our mom dated his uncle for a moment, which brought us into close contact with his family. He would babysit us when our mom had to work her second job at a liquor store. Strangely, Kaizen wasn’t the only eventual murderer to babysit us. We had another guy by the name of Khalil who ended up killing someone after a dispute at a Newark bar. Nevertheless, they were exceptional babysitters. Khalil would rip and run with our Uncle Keith, a legendary figure in the streets of Newark with an impeccable sense of style and penchant for women and the nightlife. Uncle Keith got arrested after a shootout with cops in Virginia. We attended his marriage to our Aunt Cathy in prison. Despite the location, it was a beautiful wedding. They subsequently divorced. But, we digress.

Our fortunes changed in 1992 because Bill Clinton got elected. Just kidding, that dude was terrible for poor black communities. His policies locked up more brothers than Kawhi Leonard in the playoffs. Our fortunes changed because we moved from the Spires into a three-family home on the 300 block of Myrtle Avenue in Irvington, New Jersey, a township right next to Newark. We were able to move because our mom got a new job at the VA Hospital. It was a safer neighborhood than the Spires, and only occasionally called “Murder Ave” by the locals. Our portion of the street was of particular merit as most of the families owned their homes, dating back to the ‘60s. Kaizen’s great-grandfather, a man we all affectionately called Granddaddy, owned the house where we lived. He was a WWII vet and an all-around swell guy who loved watching old-school wrestling. We moved into a one-room attic apartment on the third floor with our mom. At the same time, Kaizen, his baby brother, grandmother (Grandma Alice, who is the daughter of Granddaddy — the nomenclature in our family is a bit confusing), and first cousin moved into the second-floor apartment. After the move, we spent even more time with Kaizen and the Crossen family. We’d throw BBQs and play pick-up basketball and a game called “man-hunt.” Kaizen was an adept man-hunt player who knew how to locate discreet hiding spots, making it impossible to find him at night.

For a time, Kaizen was one of the few male figures in our lives to help us navigate the murky waters of being fatherless boys in Newark. All of the young boys in our neighborhood looked up to him. He was extremely charismatic, intelligent, and the life of any party. He was also a gifted joke-teller with an uncanny ability to mimic others. As the oldest among us, he was the leader of the block. And he led with zero fear. One summer, our bike got stolen by a neighborhood bully. We cried and ran to Kaizen, who didn’t hesitate to go searching for the bike. After a couple of hours, he triumphantly returned with the bike and made sure to beat the bully. No one ever stole our bikes again. For Kaizen, if you messed with one of us, you messed with him. And he was willing to defend us, since none of our dads were around.

However, in Irvington and Newark’s dangerous streets, there’s only so much you can do with your hands. Kaizen eventually decided to carry a gun for protection, and we can vividly remember the first time he showed it to us. It was 1995, and he had just purchased gold fronts for his teeth. You see, he was obsessed with the Wu-Tang Clan, particularly Ghostface Killah and Raekwon, who wore gold fronts. While Kaizen obsessed over the Wu, we developed an everlasting adoration for the more subdued, gangsta weed-loving Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, which caused some friendly friction between us. For an entire day, we debated which was the better group: Wu-Tang or Bone Thugs? We advocated for Bone, proclaiming that the odds of finding five guys who sang and rapped in harmony were much lower than finding nine guys with incredibly distinct rapping styles. Moreover, we argued that Bone was more successful (they’d just won a Grammy) and quietly more revolutionary in terms of their rap style. (This was before Bone Thugs cemented their legacy as the only group in history to make songs with 2Pac and Biggie Smalls.) Kaizen would not budge. He argued that Wu was more experimental and iconic, fusing kung fu, the Five-Percenter philosophy, and mafioso themes. We went back and forth, asking everyone on the block who they thought was better. Most of the women and children preferred Bone Thugs, while most of the young guys preferred Wu-Tang. We argued until the middle of the night, and then he playfully showed us his small, stainless steel 9mm gun, abruptly ending the debate. In general, logic and evidence should win debates, but in the hood, guns trump both.

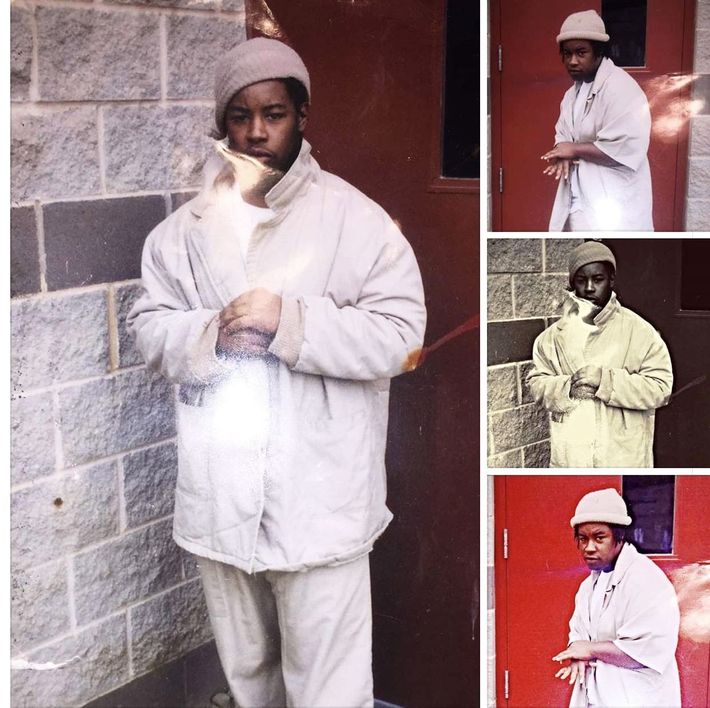

From fourth to sixth grade, we moved between Irvington and Newark. After some publications voted Newark the most dangerous city in the country, our mom decided to get us out. In a reversal of the second great migration, we moved from Newark back to High Point, North Carolina. During our time there, our mom and our stepfather fought verbally and physically (they divorced when we were 16). Despite the fighting and our stepdad’s addictions to Bobby Brown and various substances, things were relatively stable for a while. We finally had a two-parent household, and we were able to go to decent public schools, where we excelled academically. Unfortunately, Kaizen did not have a similar opportunity. He stayed in Irvington and Newark, finished high school, and gradually became involved in criminal activity. In 1998, he was arrested for selling weed in a school zone. The court sentenced him to three years in prison, which commenced his tumultuous relationship with the criminal justice system. While Kaizen struggled with the law, we continued to succeed in school. When Kaizen was released and returned to his old life in Newark, we were preparing to attend the College of New Jersey.

At TCNJ, we studied philosophy. As we became more enmeshed with Western philosophy, we drifted away from religion and spirituality and toward atheistic materialism, bordering on nihilism. We also started listening to too much Radiohead. Our academic pursuits brought us into contact with such philosophers as Søren Kierkegaard, Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, Satre, Camus, and a few other sad dead white guys. Tragedy back home would push us closer to nihilism when one of our favorite uncles — Al, a low-level drug dealer who taught us how to drive and cut our hair, but who also suffered from PTSD, depression, and substance-abuse issues — committed suicide. Uncle Al jumped to his death from a high-rise building in Newark during our sophomore year. His death fundamentally altered our perception, making us more morose and sullen. Existentialism provided a comprehensive system to understand better the alienation, isolation, and despair experienced by impoverished young black men in a largely affluent white world. Religion was inadequate. Philosophy enabled us to assess our material conditions logically. But this intellectual understanding did not address our emotional distress. You cannot rationalize away pain and trauma.

It would appear that we and Kaizen were worlds apart as we sat on the manicured lawns at our college debating Kantian metaphysics with privileged students from all walks of life, while Kaizen braved the harsh winters of Newark in search of money for his growing family. On the inside, however, we all suffered from acute post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of growing up in a war-torn inner city. We were both exposed to violence, which had an insidious impact on our psychological health. According to the National Institutes of Health, “inner-city students that experience violence are more likely to be depressed, to contemplate suicide, and to abuse substances.” Our issues with depression, suicide, and substance abuse materialized during our time in law school, at Duke and NYU; Kaizen’s did on the streets of Newark.

People don’t like to talk about mental health. Back in Newark, there was a stigma against folks who openly acknowledged struggling with it. Specifically, they would be stigmatized as crazy motherfuckers. Rather than seeing the issue as a matter of degrees, the community drew a rigid dichotomy between “normal” and “insane.” No one wanted to be deemed mad. So instead of talking about our emotional distress, we adopted strategies to cope. People have different ways of rationalizing disturbing thoughts. In college, we turned to philosophy and sports. Kaizen preferred violence, drugs, and alcohol. None of us saw a psychotherapist. We couldn’t afford it.

This isn’t just an issue in the hood. It’s pervasive throughout society. At Duke and NYU law school, we saw firsthand how the elites treated their mental health issues. Our classmates heeded a strict code of silence to avoid being perceived as weak in such a competitive environment. Nevertheless, a significant number of them suffered from severe mental health issues and abused substances. A few of our classmates even committed suicide. In fact, we know more people who committed suicide from law school than from the inner city.

During that time, we turned to drugs and alcohol to deal with our mental health issues and the stress of law school. It was jarring to study the insidious nature of our criminal justice system with white law students, while some committed the same crimes that would land black people in jail. We couldn’t help but consider the irony of it all as we consumed drugs: What if the law was designed in such a way to criminalize black behavior while simultaneously decriminalizing white behavior? The 100-to-1 cocaine-to-crack ratio, which places tougher penalties on crack usage than cocaine, seems way more plausible if written by a white lawmaker addicted to coke, who implicitly believes in white superiority. We started recognizing the hypocritical, often absurd, duality of our legal system. Whites create, interpret, and enforce the law. Those who violate the law are deemed criminals — fair enough. Whites and blacks use drugs at similar rates. Yet somehow blacks are arrested at disproportionately higher rates for the use and distribution of drugs. How is that possible? It’s only possible if black criminality is embedded in the premise of our robust legal system. If “blackness” is the crime, then mass incarceration, generational poverty, segregation, and police brutality necessarily follow.

In 2008, as we started to question the validity of the law (especially our drug laws), Kaizen was arrested for drug- and gun-related charges. He was a father looking to make money during the recession when jobs were scarce, especially for convicted felons struggling with addiction and mental health disorders. So he sold weed, which wasn’t yet a perfectly legal, billion-dollar industry. Meanwhile, as our depression and anxiety worsened, one of us attempted suicide for the first time (the other would try it at a later time for balance). We dropped out of law school, developed stoner comedic personas to justify our growing substance-abuse problem, and pursued entertainment careers. Instead of therapy, we sought fame and fortune to mask our pain. Initially, the returns were stellar: We got into film, TV, and stand-up; we performed on the Tonight Show multiple times; we recorded an hour stand-up special for Netflix, aptly titled On Drugs; and we made a substantial amount of money. But our PTSD remained untreated. So, we continued to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol. We were spiraling out of control, seeking to destroy ourselves.

After a particularly bad night with drugs and alcohol, we decided to try sobriety. We went to therapy for the first time at the age of 31 and our therapist (yes, we share a therapist — it’s cheaper, and we don’t want to pay to tell the same sad story twice) diagnosed us with PTSD and depression. We took the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) quiz, which examines abuse, neglect, and other hallmarks of a rough childhood. Our ACE score was 8 out of 10. A number closer to 10 puts you at greater risk for issues like depression, suicide, PTSD, and drug abuse, meaning this might be the only quiz in history for which a high score makes you immediately want to kill yourself.

Kaizen never saw a therapist, nor did he take the ACE quiz or have an outlet like stand-up comedy to talk openly about his trauma. His mental ailments remained untreated, which is likely why he continued to abuse substances and openly started to discuss dying in a blaze of glory. There are many ways to commit suicide. One way is “suicide by cop,” in which a person deliberately behaves in a threatening manner with the intent of provoking a lethal response from police. Kaizen would talk about going out like Scarface. Most in the family thought he was probably interpreting rap lyrics too literally. Despite several run-ins with the law, no one thought Kaizen capable of committing murder, especially the killing of a next-door neighbor on our block with whom he was friends. He was an almost-40-year-old father of two beautiful girls who loved his family and valued his friendships, but depression is a real sickness that can destroy any person. After the death of his mother in August 2018, we believe Kaizen, our cousin and brother, lost his will to live and sought to end his life when he walked down the block and opened fire in August 2019.

The final time we saw Kaizen was on May 3, 2019, a few months before his death. We were performing a stand-up comedy show in Newark in front of our family. We hadn’t been back in a few years. We did a 30-minute set, touching on issues such as drug abuse, ending gentrification, and suicide. We quoted Camus, who once said: “There is only one really serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Deciding whether or not life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question in philosophy. All other questions follow from that.” In our set, we asked ourselves if life was worth living, concluding that because of our love of Missy Elliott, indeed it was.

After the show, we hung out with our father, Uncle Keith, Kaizen, and our friend from out of town. Our father, who turned his life around entirely, training kids in the art of boxing, had to leave early. We chilled with Uncle Keith, our homegirl, and Kaizen for a few more hours. And then things got weird. Kaizen asked us to go someplace else to have a foursome with our friend. We weren’t sure if he was joking or not, but we declined. Eventually, Uncle Keith asked him to chill the fuck out, and it felt like they were about to have a duel since we assumed they were both carrying guns. Thankfully there was no shootout. But our uncle did tell us a story about his shootout with the cops many decades ago — ironic considering Kaizen’s final moments with the police. At around midnight, we hugged our cousin, telling him we loved him and we’d see him soon. Then he walked away into the darkness. It would be the last time we ever saw him alive.

On August 8, Kaizen walked down the block on Myrtle Avenue, as we all had done countless times as kids, ostensibly to ask a friend for a favor. His car was out of service, and he needed a ride to the shelter to get food. Somewhere along his walk, Kaizen got into an altercation with two neighbors, which pushed him over the edge. He retreated to our childhood home, where we had debated Bone and Wu on the porch years earlier, to retrieve a gun. Not the stainless-steel 9mm from two decades ago, but a military-grade rifle filled with ammo. He put on a bulletproof vest and walked back down the street to kill the two guys. Jason Caudle, a friend and neighbor of Kaizen’s, attempted to quell the beef only to get a bullet in the neck, later dying at University Hospital in Newark. Kaizen subsequently shot at everyone in sight, including neighbors he’d known for three decades. A cop showed up, and he shot the officer in the legs. For a couple of minutes, in the backyard of our childhood home where we played basketball together, Kaizen exchanged close to 100 rounds with cops from the Irvington Police Department. He taunted the police every step of the way, daring them to shoot him. And they obliged. They shot Kaizen multiple times as he tried to open the side door to go home for one last time. For a moment, everything went still as he bled out, inching closer to death. The bullets stopped as the cops secured the perimeter around the house. What were his final thoughts when he died? Maybe he thought about his baby brother? Or his mom? Or his daughters? We’ll never know.

It’s easy to close the book on Kaizen by concluding he’s a low-life criminal or a thug who deserved to die. Yet our understanding of history, law, philosophy, and psychology makes it impossible to conclude his story in such a simplistic manner. Kaizen committed a heinous crime, but his actions don’t exist in a vacuum. Due to onerous, racist drug laws and restrictive racial covenants, Kaizen lived in a harsh ghetto without any wealth or employment prospects. He sold weed to make ends meet. Like many others, he did drugs to cope with the trauma of growing up in a violent inner city. Oftentimes, the majority fails to contextualize the actions of the oppressed, focusing on the effects instead of the causes. They fail to understand the despair, anguish, and hopelessness felt as a result of living in abject poverty while under heavy policing. They create a false dichotomy where you’re either a perpetrator or a victim.

George Floyd’s murder is a brutal reminder that the entire legal edifice — from slavery to mass incarceration — was designed to break down black people meticulously. This isn’t accidental. This is a country made up of (imaginary) laws to aggressively protect corporations and property-owning white men at the expense of black minds and bodies. This is the underlying premise of America. Until we reject this premise, dismantle the current system, and build anew, changing for the better, our country will continue to treat black people with enmity, while white folks are allowed to violate laws, loot our spirits, and break our minds and bodies with impunity.