The internet deprogrammed Patricia Lockwood. It didn’t happen all at once. Raised in the Catholic Church, Lockwood spent the early years of her life absorbing her parents’ anti-abortion beliefs and activist language about the “Holocaust of infants.” But when she started visiting anti-abortion activist websites in the aughts, when she was in her early 20s, she was put off by the treacly graphics and coarse design — how could they be serious? These facts can’t be real, she remembers thinking then. These statistics have to be fake because there’s this little dancing-child graphic in the corner of the page or there’s a rose that’s slowly losing its petals. These websites destabilized something inside her, she said; they “opened a crack” for her to reevaluate what she had been taught.

At 38, Lockwood describes herself generationally as “between the books and the ether.” She remembers a time before the internet while still being young enough to immerse herself in it as it was developing — young enough that it could help set her life in motion. Online is where, at age 19, Lockwood met the man she would marry at age 21. It’s where she published her first writing and found her first readers through early diary blogs and poetry forums. And it’s where she uncovered the evidence she needed to shake her family’s anti-abortion stance for good: She came across infertility blogs on which women posted testimonies about what it was like to terminate their pregnancies in the third trimester. “This is the bogeyman scenario my parents talked about,” she said. But she could see that these women “really, really want to be parents.”

All that happened, though, in an internet culture of the past — no influencers jockeying for likes and retweets, no algorithms filtering what Lockwood would see. Nowadays, even anti-abortion activists are savvy with memes, and this recent internet is what Lockwood explores in her groundbreaking debut novel, No One Is Talking About This, out February 16. The author — who previously published two books of poetry and a memoir, 2017’s Priestdaddy — approaches the terrain as a disenchanted veteran. She describes the internet, which she calls “the portal,” as a “world pressing closer and closer, the spiderweb of human connection grown so thick it was almost a shimmering and solid silk.” If that sounds both intriguing and disconcerting, well, exactly.

The book features a Lockwood-like character who travels the world giving lectures, having found fame from a single post to a social network: “Can a dog be twins?” In its second half, the novel takes a left turn, as social media’s glittery absurdity is put in contrast with the offline demands of a family crisis. Throughout, Lockwood articulates her ambivalence about the internet while owning its influence on her life.

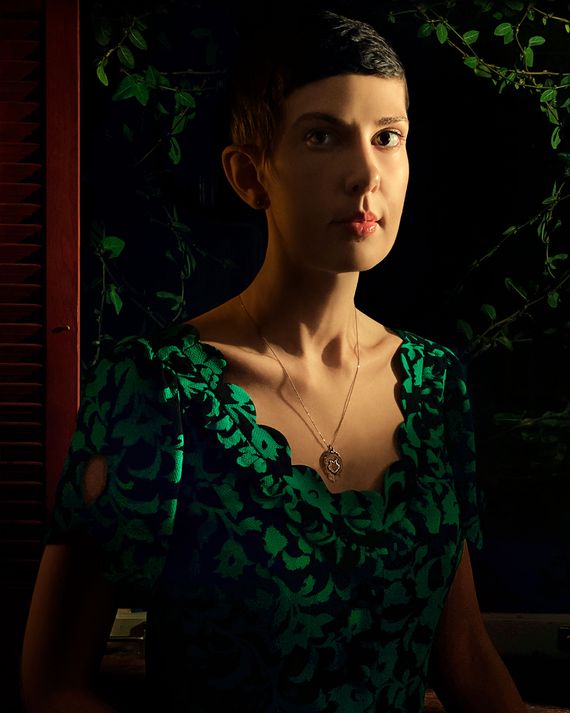

The writer, who lives in Savannah, was funny and animated during our conversations over Zoom and email despite her physical condition: She contracted the coronavirus last March and still feels its effects almost a year later. She spoke of the “excruciating pain” she has experienced while typing. It flares up when she feels stressed. “I’m just not physically cut out for this life, for this world,” she said. “My mind is insanely adapted to the present climate, the climate that’s witnessed by this book. But my body? Of course it was going to end this way for me.”

Lockwood spent her childhood moving around the Midwest with her parents and four siblings, as her father, a Catholic priest (he converted and was ordained after his marriage), shifted among congregations. She grew up partly in St. Louis, near a landfill that was a Manhattan Project dumping ground for radio-active materials; she still wonders if this has anything to do with the health problems that continue to plague her family. After graduating from high school in Cincinnati, Lockwood found herself unable to afford college tuition and felt isolated. She got a job in the children’s section of a bookstore, where she worked for only about six months. She had to quit because she regularly fainted in the aisles.

She dreamed of being a writer from an early age, and in her teens and 20s, poetry forums became a major part of her life — the closest she would come to a formal writing education. These websites were not exclusive; in 2001, you could find them by typing “poetry” into a search engine. The users she met in communities with names like Eratosphere and the Gazebo were international and intergenerational, hobbyists and ambitious poets. The poet Jee Leong Koh was a regular on the Poetry Free-for-all forum (PFFA) at the same time as Lockwood in the early aughts. “She had a real eye for a powerful image and a willingness to venture into darker material,” he remembered. Lockwood also met her husband, Jason Kendall, in one of the forums; he drove from Colorado to Ohio to meet her face-to-face. Feedback could be merciless, but the regulars really cared about one another’s work. The forums gave Lockwood the structure and company she lacked IRL at a time when she was living with her parents before getting together with Kendall. There was a “Christmas-morning feeling when you would post this poem, and you would think, I might get a comment,” Lockwood told me.

The traces of teenage Tricia that can still be found deep in the internet archives are striking in their consistency: The earnest, brazen, filthy, whimsical weirdo voice threading through her poetry, criticism, and fiction is fully present in her earliest posts. One of the first entries on her Diaryland page, an online journal she updated from around 2000 to 2006, is a joke that has all the ingredients (bonkers setup, playful use of caps lock) of something she might later post to Twitter; it supposes that “gentlemen dinosaurs” failed to satisfy their partners and that they all died in “AN EARTHQUAKE CAUSED BY THE VIOLENT AND EARTH-SHATTERING MOVMENT OF LADY DINOSAURS’ VIBRATORS.”

Lockwood had been submitting her poetry to unknown editors since her early teens. During our call, she stood up to grab a book from her shelf and proudly waved it before the camera: The Market Guide for Young Writers. She has had it forever. Inside are the addresses of various publications, with double crosses beside the ones that are especially selective. Lockwood showed me the personal touch she had added next to the names of her dream publications: her fingerprint in blood.

In 2011, double-cross-tier publications started to open their gates, and The New Yorker published one of her unsolicited poems. (Once your work is lifted from a magazine’s slush pile, Lockwood said, you will be “chasing that thrill for the rest of your life.”) She considered writing a book of sexts, a bit she began after moving on from the poetry forums to Twitter. (A representative example: “Sext: I am a living male turtleneck. You are an art teacher in winter. You put your whole head through me.”) But the sext-writing process — outside of the instant feedback from Twitter — didn’t translate well into the composition of a manuscript.

Then, in 2013, one of her poems went viral after being published on the now-defunct blog the Awl: “Rape Joke,” a high-wire act of vulnerability, fury, and comedy about a real-life traumatic experience she had had at 19. The poem was elevated by its own grace and internet alchemy; it hit at a time when comedians were debating whether it was acceptable to joke about sexual assault. Her work has now been widely acclaimed for the better part of a decade, and she writes regularly for publications like the London Review of Books. But, as she put it, “I lived in the slush pile for way, way longer than whatever I’m living in now.”

Lockwood describes the editor of her past three books, Paul Slovak, as the least-online person she knows. “I’ve accompanied her on this journey despite not knowing what a ‘binch’ is,” Slovak told me. “I’m still not sure that I do.” Slovak and Lockwood connected when another one of his authors passed her work along in 2013. He was struck by her distinct voice and the “tenderness” of her writing: “She can be extremely profane and funny and yet offer these devastating and profoundly sad meditations on human experience.”

These have often included writing about health crises, a through line in Lockwood’s recent work and in her life. Priestdaddy begins with events that unfolded after Kendall was diagnosed with a rare type of cataract; the couple managed to raise funds for eye surgery online but still ran out of money and moved in with her parents in Kansas City in 2013. (They eventually moved back to Savannah — where they had lived before this crisis — in 2016.) Priestdaddy was a critical and commercial success, but the years after its publication were painful. In 2017, Lockwood’s older sister had a baby with a rare, life-threatening genetic disorder; he died a few months after his birth. Soon after, Lockwood had to embark on tour for Priestdaddy in Australia. It was disorienting to experience grief away from her family. A year later, another of her sisters became pregnant with a baby that had a different life-threatening genetic disorder. This time, Lockwood decided to stay with her younger sister and get to know her niece for as long as she possibly could. That baby also died, in 2019.

No One Is Talking About This draws on these painful experiences. The first half of the book replicates the feeling of being online — it’s dreamy, frenetic, and full of esoteric jokes. That humor turns into a disorienting undertow in the second half as the protagonist is yanked into a fictionalized version of the Lockwood family’s distressing circumstances. The protagonist’s pregnant sister lives in Ohio, a state with oppressive laws restricting abortion. When complications threaten the sister’s life, the protagonist offers to drive her to another state — but it would be dangerous for her sister to travel, and they both know “their parents would never speak to them again.” They stay in Ohio, and her sister has the baby. In another scene, the protagonist sits in a car with her mother as her mother weeps. The protagonist can’t bear to tell her that the “spurting three droplets” emoji in the texts her mother sends — as the extremely online understand — aren’t code for water or tears but for jizz.

In real life, Lockwood sounded exasperated when she talked about her own health issues. Last March, returning to Savannah after delivering a lecture at Harvard, she noticed the guy behind her on the plane was coughing; a few days later, she came down with COVID. The long-haul symptoms, which she detailed in a vivid July essay for the London Review of Books, never quite went away. Some, such as phantom smells, are mysterious, while others are debilitating and include migraines, tachycardia, and intense neuropathy in her hands. She was in this unpleasant physical and mental state as she worked on final edits for No One Is Talking About This. “It added a third dimension to the book,” she said. “If I’m suffering diminished capacity, am I still the person that I have always known myself to be?”

As much as the book is about a physical body alienated from an online mind, it also grapples with the capriciousness of fame. Lockwood is much more accomplished (and has even more viral tweets) than her protagonist, who travels the world on the back of a single joke. The book invites you to think that maybe the character — plucked from “the portal” to become a public figure — doesn’t deserve celebrity. But it also seems to ask, Who does? The path to renown has never been equitable, even as social media flusters the closed systems of traditional publishing. It is unusual for a New Yorker contributor not to have a college degree, but it is normal in America and it is normal on the internet. Those old poetry forums welcomed everyone. That doesn’t mean they weren’t rigorous.

When Lockwood was staying with her sister during the troubled pregnancy and her niece’s short life, she couldn’t focus on books. Instead, she revisited her favorite internet writing from the aughts: the LiveJournal of former model Elyse Sewell, Mimi Smartypants’s Diaryland, Lisa Carver’s online sex diaries. Writing with quirky humor and open, intimate voices. No politics, really. No Trump. Their influence comes through in Lockwood’s novel, lodged at the root of her formal daring: an embrace of writers like W. G. Sebald and the postmodernist David Markson alongside Diaryland, Carver, and the perfect kooky sext.

Where is Lockwood without the internet — as a writer and a person? I asked her over email. As I waited for her reply, I watched her make a joke on Twitter about how she’s worried she might sound in interviews: “the internet?! now that’s a horse … you can’t … put back in the barn!” Later that day, she got back to me. “Without the internet I’m Emily Dickinson’s little ugly daughter, probably,” she wrote. “Lowering my little cakes out the window, filling a drawer with my scraps, every once in a while sending a really weird letter to the editor of The Atlantic. Possibly that life would have been healthier for me. I would have known how to bake.”

*This article appears in the February 15, 2021, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!