HBO’s prestige legal drama Perry Mason is, of course, a work of fiction based on the character Raymond Burr immortalized on the ’50s and ’60s TV show. However, the first season included nods to famous real-life Angelenos and incidents like radio evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson and the horrific kidnapping and murder of Marion Parker. The second season, which premiered on March 6, is no different. Michael Begler, who along with his writing partner, Jack Amiel, serves as the new showrunner for the series, broke down some of the historical influences for Vulture.

Perry Mason’s sophomore season tells a “have and have nots” story through the guise of a murder mystery: It revolves around the death of a wealthy and well-known white man and the brothers Mateo Gallardo (Peter Mendoza) and Rafael Gallardo (Fabrizio Guido) — Chicano men from a completely different area of Los Angeles — who are charged with the crime. This season looks at the power of not just wealth but access: to the media, to housing and, yes, to decent legal representation.

Vulture did the gumshoe investigating, speaking with Begler and historians, to reveal some of the season’s real-life inspirations. Want to sound like you know the difference between the truth and Hollywood spin? Study this list and no jury in the world would convict you.

Ned Doheny

This murder victim at the center of season two is Brooks McCutcheon (Tommy Dewey), the Icarian son of the prosperous (and nefarious) oilman Lydell McCutcheon (Paul Raci). When we meet him in the premiere, Brooks desperately wants to step out of his dad’s shadow and make a name for himself. He does; just not the way he expected. The town will be buzzing when they learn his body was found in his yellow convertible with a bullet hole in his head, as happens at the end of the episode.

Begler says the murder is inspired by a real-life killing, the 1929 shooting deaths of 35-year-old Edward Laurence “Ned” Doheny Jr. and his assistant, 32-year-old Hugh Plunkett. Rather than in a beachside car, the pair died in Doheny’s illustrious home, known as Greystone Mansion, and the shootings occurred after Doheny Sr. was implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal that brought down President Warren Harding’s administration. It was the society killing to gossip about among the still-forming Los Angeles nouveau riche.

“Here was one of the wealthiest families in the city, and the scion of that family gets murdered,” Begler says. “This was a beloved young man and the prince of the city, and how did that affect people? At his funeral, they’re spreading out into the streets; they couldn’t hold them in the church.”

Although commonly talked about as a murder-suicide, Dohney and Plunkett’s deaths have officially never been solved, and theories range from a lovers’ quarrel gone wrong to fallout from the Teapot Dome scandal. Intriguingly, as Begler notes, Dohney’s extremely powerful and corrupt dad brought in his own security force to “take over” the investigation — which may have had something to do with the case’s lack of resolution.

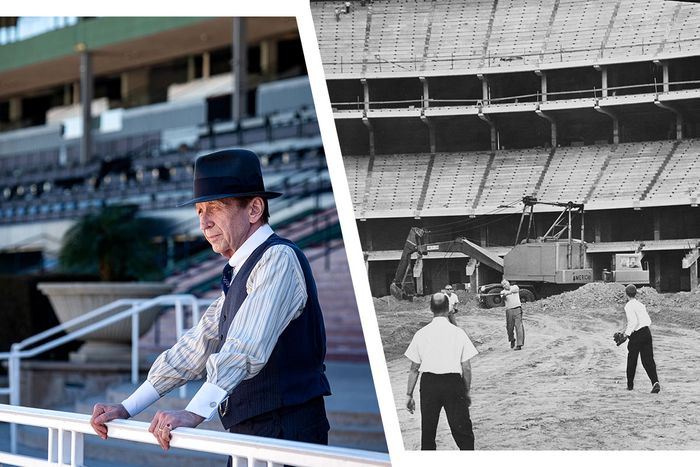

Chavez Ravine

Prior to his death in the Perry Mason premiere, Brooks’s big swing was to build a baseball stadium in the hopes of luring a national team out to what most still considered a dust bowl. He bragged to his dad about all the advertising he’d lined up, and his last order of business was a failed attempt at sweet-talking a noted ballplayer into spreading the word.

Brooks may have been ahead of his time. In real life, the Los Angeles (née Brooklyn) Dodgers didn’t move to L.A. until the late ’50s, and Dodger Stadium didn’t open until 1962. The ballpark also wasn’t built on empty desert — there were people who lived where it would eventually stand. Up until the late ’40s, the area that is now known as Chavez Ravine was home to more than 1,100 families who made up three Mexican American neighborhoods; it was one of the few places in the city where the members of these communities could own homes. After they were (barely) bought out and then forced out, the area was razed — first in the name of urban renewal and public housing and then, after years in limbo, for a fancy dome-shaped stadium.

Even if it’s set decades before the Dodgers’ opening game, Perry Mason’s showrunners know that racism was still rampant in the city at that time. Begler references a government-sponsored program in the ’30s that deported Mexicans — and even native-born Americans of Mexican descent — so that they wouldn’t compete with white workers during the Depression. The show doesn’t directly feature these deportations, but it does, Begler says, explore “the sense that you can be stepped on and pushed about.”

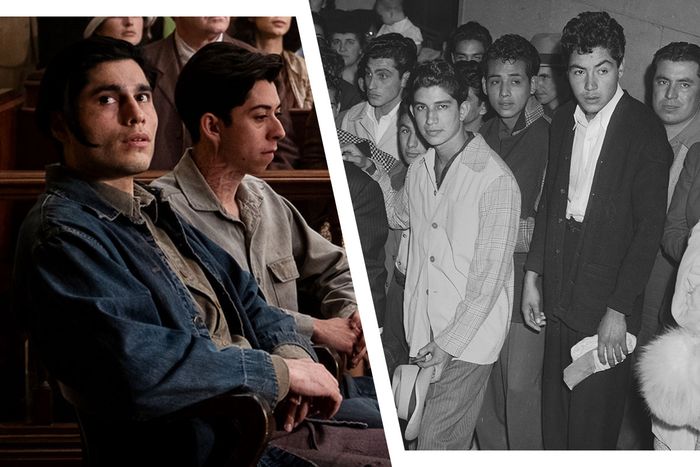

Sleepy Lagoon

The arrest of the Gallardo brothers — and the subsequent media coverage — may not have been a direct inspiration for Perry Mason’s second season, but it’s very reminiscent of the aftermath of José Gallardo Díaz’s killing in 1942. The 22-year-old was found unconscious with stab wounds near a watering hole called Sleepy Lagoon. The LAPD rounded up anyone they could find, and 24 boys and men were indicted. Two requested separate trials, but Kim Cooper, a historian who runs the Los Angeles historical-tour company Esotouric, says that the 22 men who stood trial together before an all-white jury weren’t allowed to bathe or change clothes. The People v. Zammora became the largest mass trial in California history, resulting in 17 convictions ranging from assault to murder in the first degree (12 convictions were later overturned).

“The trial became an awakening for the progressive white community about just what minorities in Los Angeles are facing,” Cooper tells Vulture.

Like People v. Zammora, the Gallardo brothers’ trial becomes a media sensation, fitting with season two’s exploration of the ways in which radio influenced the public. Other examples include Sean Astin’s grocer Sunny Gryce’s use of advertising to help squash a protégé turned competitor and a radio personality inspired by real-life antisemitic and conservative Catholic radio personality Father Charles Coughlin. Perry Mason, which takes place in the ’30s, does slightly fudge when radio became widely available in cars (the first commercial in-car radio came out in 1930, but it was extremely expensive).

The Monfalcone and the Johanna Smith

The second season of Perry Mason opens with a fire on a gambling ship, an arson attack that we soon learn is tied to Brooks and his connection in the LAPD, the shady detective Gene Holcomb (Eric Lange). Such police corruption targeting gambling boats had historical precedents. “There’s even pictures of the police coming alongside but the people on the boat shooting hoses at them,” Begler says.

Joan Renner, a historian who runs Deranged LA Crimes, tells Vulture that two ships were destroyed by fire during this time — The Monfalcone, which went down in 1930, and The Johanna Smith, which burned in 1932 — though it’s impossible to know for certain if arson was the cause.

Anita Loos

The second season premiere also introduces the delightfully brassy Anita St. Pierre (Jen Tullock), a love interest for Juliet Rylance’s Della Street. Anita’s a successful screenwriter who came up at a time when women permeated all aspects of Hollywood.

Begler says the character is based on Anita Loos, an extremely powerful screenwriter at the time who studied under The Birth of a Nation director D. W. Griffith. Loos is now best remembered for writing the novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and the Broadway play Gigi, an adaptation of the Colette novel.

“She was very glamorous and a little avant-garde for the time,” Begler says. However, he doesn’t know if there’s any evidence that Loos — who was twice married to men, the second time to actor John Emerson — was queer or even confident enough to give another woman her number at a time when homosexuality was illegal.

She was, at least, open to going to their parties and telling tales well after the fact.

In 1972, Loos told Interview magazine that “I think women can get a lot further by covering up and going underground than by waving a flag. There was a big group of very beautiful lesbians in Hollywood, quite a number of them. I got dragged to a cocktail party one day and they were all there, done up in chiffon and hats and being very elegant. And in walked [closeted gossip columnist] Elsa Maxwell in a suit with cuffs and a necktie and one of them said, ‘Oh look at Elsa! Giving it all away!’”

Emma Summers

Later in the season, audiences will meet Hope Davis’s self-made single woman of means Camilla Nygaard. Begler says she’s rooted in Summers, an oil baroness who came out west as a piano teacher and used the small amount of money she had to buy some wells.

Camilla’s house and life are meant to reflect a modernist lifestyle. She has a Pilates machine, swims regularly, and is a major donor to the arts. Begler says that the architecture at her house is meant to look more modern than the Gothic styles of the time and that “it was important to have something to show that it separated her from the old guard; of Lydells of the world.”

Jonathan Club

Los Angeles loves its velvet ropes, both literal and figurative. The private social club Jonathan Club has been around since the late-19th century. According to its website, it is — ironically, given its exclusive nature — named for “Brother Jonathan, a caricature predecessor of the iconic Uncle Sam.” There’s a downtown and a beachfront location, the latter opened in 1927.

One of Brooks’s last conversations with his father happens at an exclusive beachfront club called the Oceano Club, which was inspired by Jonathan Club. (The real club is still up and running, but this scene was filmed at the Adamson House in Malibu, a national historic site that was a private residence built 1929 for Rhoda Rindge Adamson, the daughter Frederick Hastings Rindge, the last owner of Malibu, and her husband, Merritt). In the show, Lydell tells Brooks that, in the spring, he appreciates the view of the ocean. But he feels like the place, like his offspring, didn’t live up to its potential.