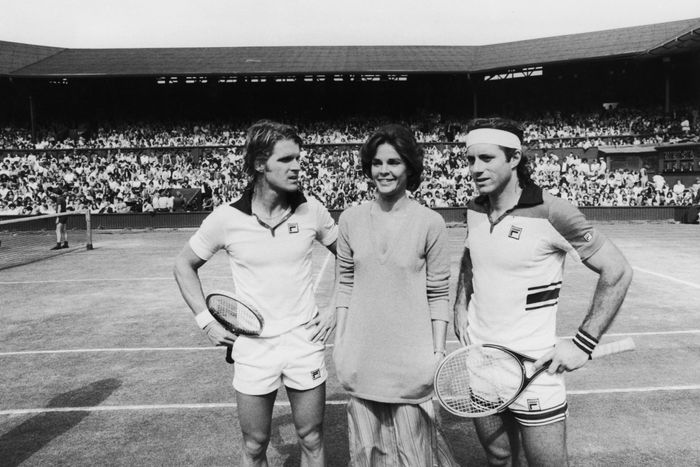

The year was 1979. Ali MacGraw, who had lit up Love Story almost a decade earlier, was officially back, having just ended her own volcanic marriage to Steve McQueen, who had prevented her from taking acting work for five years. Dean Paul Martin, the famous singer’s son and a recent divorcee, could barely act, but he could definitely swing a tennis racket, having competed at the Wimbledon Championships for four years running. Knowing this, Love Story’s megaproducer Robert Evans — a tennis fanboy who happened to be MacGraw’s second ex-husband, before McQueen — got an idea: pair the two in a sports romance and make it the hottest, most authentic tennis movie Hollywood had ever made, and call it Getting Off. The movie Evans wanted made some sense, artistically and financially, in a Hollywood decade dominated by star power and crowd-pleasing sports pictures like Rocky and Bad News Bears — so it’s too bad that the movie he actually served up is by most accounts a cinematic bus crash.

Players, as the film would eventually be retitled, is notorious. An overwrought, overlong, two-hour clunker, it’s a series of flashbacks that Martin’s tennis ace Chris recalls of his romance with MacGraw’s Nicole as he battles through a championship match at Wimbledon in the present. Critics cited problems with its overly melodramatic script, slapdash structure, and flat performance between the two leads, whose chemistry never rises above a C-minus. Its credited screenwriter, Arnold Schulman, actually sued Evans after the producer hired “six or seven” writers to rewrite the script, which culminated in Schulman purchasing full-page ads in the Hollywood trades slamming the movie in retaliation. It opened to terrible reviews and worse box office returns, only making back its $6 million budget in the home-video rental market. On Sneak Previews With Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, the critics called it “too corny to be believed.” It has never made any noteworthy lists of great sports movies (or even iconic tennis scenes). The Los Angeles Times would later label it a “disaster” in a profile of Evans, in which he suggested its failure was “set up” and that in its first screening in New York, audience members had been “instructed to laugh” at MacGraw’s line readings.

Whether rigged screenings were a legitimate concern or invented excuses after the fact, Evans’s protest speaks to a dynamic that checkered Players’ release — which foregrounded its behind-the-scenes drama and MacGraw’s turn as an unsatisfied wife having an affair with a strapping young ace. But here’s the rub: What most of its critics missed is that while the love story in Players may be laughable, the movie is dead serious when it comes to tennis. To watch it today, as a grainy VHS rip on YouTube (no DVDs were pressed), is to experience a film fundamentally with its head in the game — laser-focused on portraying the sport, to a fault. When it’s not spending time on the tryst, Players does justice to the tension, aesthetics, training, and thrills of tennis, to the exclusion of all other narrative concerns, and the visual choices it makes are what distinguish the film more than anything else.

The film opens at Wimbledon, on location at the Championships (“the first time that the club has ever allowed anything like that,” Evans hyped ahead of release). Its first scene is composed almost entirely of close-ups of the two players’ stressed-out faces as they wait in the same claustrophobic waiting room for their match to begin. Chris and his opponent Guillermo Vilas, an actual pro, playing himself, chew their gum, shift their feet, rub their faces, and tap their fingers in silence. Within minutes, they emerge onto the court, and the Wimbledon segments begin in earnest: The camerawork is almost documentarian with wide shots of the players and crowd framed as if you were watching the match on TV. The BBC’s “voice of tennis” himself, Dan Maskell, provides commentary. The first supporting cast member credited is the tennis champion Pancho Gonzales, seen in the stands, clapping and pumping his fists. With the preamble out of the way, the scene cuts to a flashback of Chris as a child, watching Gonzalez on TV playing a championship just like this one.

This opening and its first flashback cut establish a visual pattern the film’s best sequences tend to follow. In the same way the camerawork in boxing films like Rocky and Raging Bull thrust viewers into the ring, Evans and Players director Anthony Harvey and cinematographer James Crabe borrow from an aesthetic and a vibe that tennis fans in 1979 could instantaneously recognize, finding a kind of realism along the way. It’s not unlike Le Mans — another sports film made earlier in the decade with a structure split between grittily authentic, on-location racing scenes that dominate the movie, with laconically written drama sprinkled in. (The fact that Le Mans starred Steve McQueen before he met and married MacGraw is interesting to consider in retrospect.) If Evans and company learned anything at all from Le Mans that they applied to Players, after getting those pre-match close-ups out of the way, it’s a sense of visual detachment from the players’ athleticism, replicating the experience — and the excitement — of watching a tennis match live on TV. Throughout, composer Jerry Goldsmith’s score buoys the action marvelously. The movie wants its spectators to follow along.

And for all the hate it’s gotten, fellow filmmakers appear to have followed in Players’ footsteps. From what we can see so far, Luca Guadagnino and Zendaya’s upcoming film Challengers — which also pairs the sport with steamy seduction — might owe something to it. And it’s impossible to watch without clocking the similarities to other recent tennis portrayals onscreen, like Borg vs. McEnroe (a young John McEnroe also cameos in Players) or the hysterical sports mockumentary 7 Days in Hell. In The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson shot the erstwhile prodigy Richie in an outfit that nearly mirrors the one Guillermo Vilas wears in Players. Quentin Tarantino defended Players once, specifically to shout out Martin’s game as Chris — “While I didn’t necessarily need to see him star in anything else, as a tennis pro he’s pretty fucking convincing” — and the later training montage, in which he goes up against and gets coaching from Pancho Gonzales.

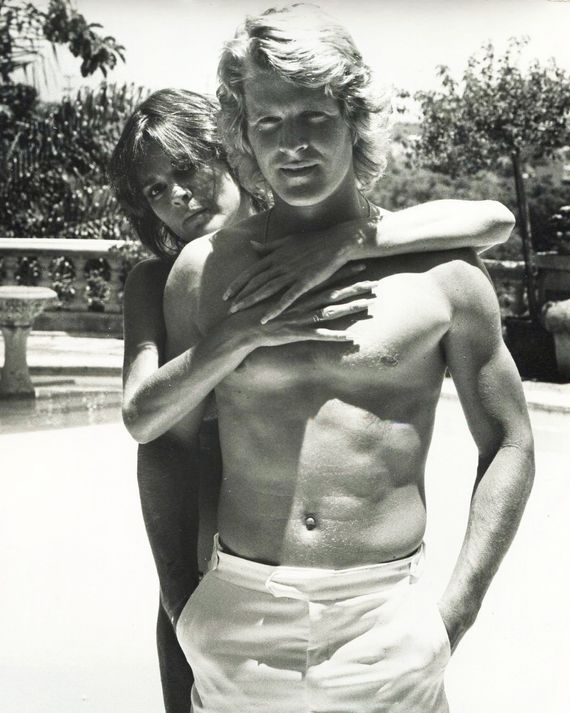

Though Tarantino didn’t have anything kind to say about the film’s romance, that aspect of the film too, to a lesser degree, still revolves around the aesthetics and athletics of tennis. Chris meets Nicole as he’s rescuing her from a car crash, in an outfit that reveals most of his physique: a tight-fitting crop top, shorts that barely cover his crotch, and a thin film of sweat. It takes a few scenes for their love story to blossom, and she only really falls for him once she sees him play — and return a volley from between his legs.

For how wrapped up her personal life was in it, MacGraw didn’t excavate much of the experience of making it in her 1991 autobiography Moving Pictures. It was the second acting job she had taken after half a decade offscreen; by her own account, she needed the money and the production was messy. But she did devote a couple pages to an anecdote about how she’d been grilled on its European press tour about whether she felt bad for taking the paycheck for such a terrible film, as if she had been the sole reason it sank. “Interviewers would boil it down to ‘God, this film is awful,’” she wrote. “It was as though I were standing on the bow of the Titanic, spotting the iceberg, and saying, ‘Well, just aim for my heart.’”

But Players is more a noble failure than the disaster it’s been made out to be, despite its messiness, checkered history, fall into obscurity, and whopping 17 percent score on Rotten Tomatoes. (They count Tarantino’s review, which is now only accessible via the Wayback Machine.) In the end, it became a relatively minor red mark on Evans’s career, the highs of which include producing hits like Rosemary’s Baby, Chinatown, and The Godfather, while the lows include a 1980 cocaine-trafficking conviction and, later, getting mixed up in a murder investigation. Schulman, the screenwriter who took ads out against it, fully disavowed any ownership, once telling film historian Pat McGilligan that “not a word” of the script was his, but watching it nearly 45 years later, you could get away with not paying much attention to the dialogue. Tennis matches should mostly stay pretty quiet anyway.