So far, on Presumed Innocent, we’ve heard a lot of talk from Raymond and Rusty about Nico and Tommy’s weak case. It’s true that Rusty looks very, very bad — from his obsession with Carolyn to the fact that he was the last to see her alive and his relentless lying, there’s little reason to be optimistic about his innocence. But, as Nico points out to Tommy repeatedly, evidence that proves Rusty’s culpability has yet to emerge. This issue functions as something of a dividing line between each of the pairs’ prosecutorial styles. From the pilot’s opening sequence, Rusty has waxed poetic about a prosecutor’s responsibilities to the burden of proof, an ethos that is complemented by Raymond’s no-BS attitude. Tommy, on the other hand, is running the risk of basing his entire case on a round hole when all he has is a square peg.

Of course, Rusty’s hyperfocus on evidence is an easy way to displace attention on himself and replace it with facts he hopes will somehow absolve him; he said as much to Raymond when he admitted that all he wants is someone at whom to point in front of the jury (not exactly what I would call justice). However, the evidence he has against Brian Ratzer — the owner of the second sperm sample that Carolyn concealed from the rest of the prosecution in the Bunny Davis case — is not totally infallible. Okay, the man’s semen was found at the scene of the crime, which doesn’t suggest anything great. But Rusty is reaching to make a connection between that fact and Carolyn’s murder, which seems to me a Molto-Della Guardia move much more than the play of someone who is devoted to hard facts. Rusty is pursuing Ratzer based on the notion that it is highly unlikely that he wouldn’t have anything to do with Davis and, therefore, Reynolds, her convicted murderer, since his sperm was found at the scene of the crime. Nico and Tommy, on the other hand, are intent on proving Rusty’s culpability by demonstrating how unlikely it is that Rusty wouldn’t have murdered Carolyn, given, well, everything.

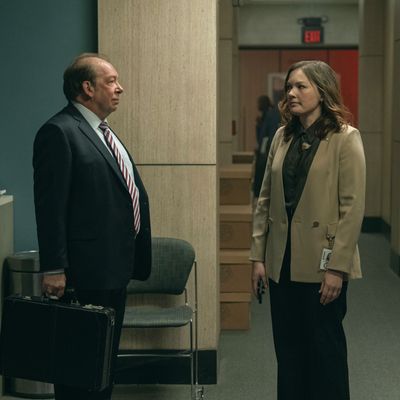

In the interest of untangling this colossal mess, let us go over what Tommy and Nico do have on Rusty, as Raymond does when he meets with them to negotiate the charges, hoping they’ll agree to three years’ obstruction of justice (the charge that Nico was trying to persuade Tommy to drop in the previous episode):

- Rusty’s obsession with Carolyn was teetering on the edge of stalking

- He hid his affair with her from the entire office, save a fellow P.A. named Eugenia whose allegiances lie with Rusty and whom Tommy is putting on the stand

- He was the last one to see Carolyn alive

- He was at her house on the night of her murder (another omitted fact)

- And breaking new information just in from Dr. Kumagai’s office straight into Molto’s slimy hands: Rusty’s skin was found under Carolyn’s fingernails. This last one is pretty bad.

There is also something that Molto and Della Guardia have on Rusty that no one except Mya Winslow, Raymond’s associate lawyer, has brought up yet. Going over the timeline of the night of Carolyn’s murder, Rusty falters repeatedly at this simple prompt: When you got to her house, what happened? He runs various scenarios through his head: him being aggressive toward her, her being aggressive toward him, mutual aggression, mutual pleasantry, straight to sex on the floor, straight to crying. He settles on: “We argued.” Relying on metadata, Mya can calculate that Rusty was at Carolyn’s for 51 minutes, which she thinks is unusually long for an argument. Clearly, she and I have different confrontational styles. I mean, 51 minutes, why not? They have a lot to get through. They’re having an illicit affair! They work together! They both have children! They cannot physically stop taking off each other’s clothes! As she is reviewing the timeline with him, Raymond asks whether Mya thinks Rusty should go on the stand. “There is no way we let that man anywhere near the witness chair,” she says without missing a beat.

Mya acknowledges something important to the trial: Rusty doesn’t exactly have an acquittable personality. If he sat in front of a jury tasked with determining his fate and acted the way he has with members of his own defense team — Uh, what happened was, uh, what happened was that … uh, what happened was — it would be easy for them to believe the prosecution’s story. Whether or not this is something that Nico and Tommy will explore in the courtroom remains to be seen, but it would be pretty stupid of them not to. The way Rusty oscillates between honesty and omission is disorienting, almost sickening. Add to that a bratty, this-can’t-be-happening-to-me vibe, the same one we might encounter at say, the trial of a rich kid who hit someone with their car, and you have a recipe for one very unsympathetic defendant.

It’s not like Raymond harbors any delusions about Rusty’s character, either. Like Nico speaking with Tommy, he doesn’t mince words, but unlike Nico, he doesn’t seem happy to discover the ugly truths about his friend. “Shame is something that you put on yourself, self-absorbed, self-centered,” he tells Rusty. “Guilt is more about owning and feeling the pain you’ve caused others. I don’t doubt that you feel shame.” Most of “The Burden” is about the subtle line that separates shame from guilt, according to this definition. In the opening scene, briefly after taking out his anger on Kyle — whose picture in front of Carolyn’s house he had just discovered; this piece of evidence becomes lost, even irrelevant, as the episode runs on — Rusty yells at Barbara that at some point she’s going to have to “take some fucking responsibility,” which understandably makes her storm off furiously. If my husband, who had been cheating on me for more than a year, whose affair produced a child, and who was being accused of murdering his mistress quite convincingly, told me to take responsibility, I might commit a crime myself.

Rusty does apologize to Barbara about this remark, and later on — after she takes an exit onto the High Road and doesn’t have sex with the hot bartender, who moisturizes his hand with weed cocoa butter (?), instead coming home to have stranger-style sex with Rusty — they have a moment of disarmed honesty. Barbara does want to take some responsibility for the distance that ultimately led to the demise of their marriage, but Rusty is also honest about what drew him to Carolyn: She wasn’t Barbara. As Rusty speaks, you can feel the extent of his shame but not of his remorse; we don’t get the impression that Rusty wishes he could take his affair back. It’s not that he did it that torments him; his motives are quite clear to himself. It’s the fact that it all blew up in his face so uncontrollably.

The conviction with which everyone accuses Rusty of wrongdoing angers him, yet he is incapable of realizing that he does the exact same to others; it’s how the system he has long upheld and defended works. This is obvious in his treatment of Ratzer. Detective Rigo is literally slack-jawed at his tactics. She is the one to find Ratzer through Ancestry.com, and when they go over to his house together, Rusty’s aggression as an investigator ruins Rigo’s game. While she works to make herself approachable, Rusty comes out guns blazing. “You know what you did,” he says, way too confidently, before threatening to tell Ratzer’s wife that her husband’s sperm had been found at the scene of a sex worker’s murder. It alienates Ratzer completely, not that he gives off a particularly nice impression; he yells at his wife and is easily agitated, and you have to give it to Rusty that it’s pretty obvious the guy knows something. Speaking with him, though, the irony appears to be lost on Rusty that he accuses Ratzer with the same confidence that Molto accuses him of Carolyn’s murder.

In fact, there is much about this entire situation that appears to be lost on Rusty. One night, he wakes up from a dream, or a nightmare, or a memory perhaps, of bludgeoning Carolyn with a fire poker to find Barbara in the garage, scrubbing Kyle’s bicycle clean. She doesn’t want to take any chances, and when Rusty tries to reassure her that Kyle is not yet a suspect in the investigation, she tells him: “Sometimes I think you forget our son is Black.” It’s like Raymond said: tormented by shame, Rusty loses sight of guilt, of all the ways in which his actions might harm his family, directly or indirectly. You’d expect more out of someone who allegedly has been through so much couple’s therapy.

Dr. Rush, for her part, is finally starting to reconsider her relationship with the Sabiches, and it’s about time she did. She sees Kyle briefly but makes no progress. Accepting that the Sabiches’ situation has gotten way out of hand, she finally recommends that each member of the family see their own therapist, and she doesn’t waste any time calling dibs on Barbara. The scene also explicitly sets up the fact that Dr. Rush is a smoker — we see her taking a pack of cigarettes and a lighter from her desk — so we’ll be on the lookout for how that will pay off later.

Therapy functions as a gravitational force in Presumed Innocent across versions: In the novel, which came out in the lateish ’80s, when therapy wasn’t as widely or openly practiced, Rusty sees a therapist, one Dr. Robinson who is more of a silent interlocutor than an actual character. The dynamic is a clever means to present backstory and exposition in an organic way, particularly in a book that is written in the present tense. In the show, which thoughtfully adjusts the role of therapy in the story for the current moment, the practice seems like an exculpatory tool that Barbara and Rusty can wield at one another. It’s questionable whether or not anyone is making any actual progress with Dr. Rush; what’s important is the notion that this is a modern family willing to reckon with their own limitations.

I wonder if Tommy Molto goes to therapy. Probably not, since his inextinguishable smirk appears to be the product of a lot of repressed anger and jealousy. At this point it’s pretty obvious that his problem with Rusty has everything to do with women. Discussing the fact that Eugenia is on Rusty’s side with Nico, Tommy suggests that’s only because she is in love with him, a sudden idea that even Nico picks up on, reminding him once again to focus on facts and evidence. “I’m my best prosecutorial self when I’m angry,” Tommy says by way of defense.

The episode closes with a phone call from Raymond to Rusty, delivering the unfortunate news that his skin has been found under Carolyn’s fingernails. Incredulous, Rusty becomes conspiratorial — “It’s a lie!,” “They’re trying to frame me!” — and Raymond’s level, resigned tone serves as a foil to his full-on freakout. I loved the chaos of this sequence. As Rusty loses it on the phone, someone starts to aggressively knock on the door. Jay screams for her father, and the house suddenly becomes a tornado of sound, merging voices, cries, knocks, and heavy breathing; Rusty yells at Barbara to not call the police as he looks through the sidelite to see Brian Ratzer, who looks like he’s about to ready to murder for real. But not before Rusty beats the living daylights out of him. So far, other than perhaps rightfully jumping at Kumagai’s neck, we’ve seen Rusty be violent only speculatively — in a dream, a vision, a nightmare, or otherwise ambiguously. Now, as the stressors from various areas of his life collapse — the trial, his family, his guilt, and his shame — we know our guy really has it in him.

Addendum

• I’m really enjoying how the show foregrounds the political fighting between Nico and Raymond — it makes the story so much juicier. Because the result of the trial is the direct interest of several different characters, it makes the stakes that much higher. I thought at first that the show missed an opportunity by resolving the election so quickly in the pilot, but the way that power struggle has seamlessly transferred to the dynamic between defense and prosecution teams is really satisfying.

• Though I know it’s something of a David E. Kelley trademark to suffuse the story with hints of what may or may not have happened, particularly as a way to illustrate how tormented Rusty is by his love for Carolyn, there’s something frustrating to me about the constant speculative interjections. There is plenty to doubt Rusty on, even if the events were played straight. We have double- and triple-understood that this is not a man to be trusted. Let’s get on with it!