Every five minutes or so, I worry again that I should tell Jeff Tweedy we can stop writing our song now.

We’ve been sitting still together for the past half hour, cradling weathered Martin acoustic guitars, in a cramped corner of The Loft, the labyrinthine two-floor recording studio, rehearsal space, business office, and bunkhouse his band Wilco has maintained in a northwest Chicago neighborhood for two decades. Crowded with former gas-station signs that read “Wilco To Go,” Clash posters salvaged from Tweedy’s childhood bedroom 300 miles south after his father died in 2017, and a bewildering number of instruments and electronics to choose from, it doubles as a de facto museum and working shrine for one of this century’s most successful rock groups.

A week earlier, on October 13, Tweedy released his second book since 2018, How to Write One Song, in conjunction with his third solo album in that same span, Love Is the King. An incisive index of exercises and jocular advice for any aspiring lyricist that also works as an empathetic self-help book for anyone suffering self-doubt, How to Write One Song made me, a songwriting novice, wonder if Tweedy might teach me how to do what the title promises. He agreed to try, so long as I covered my face and kept my space. But soon into our two-hour exercise, it seemed like we’d maybe both overestimated our respective abilities as teacher and student.

“How about, ‘Feed my misery?’” Tweedy wonders after 100 minutes, glancing up from his strings and bursting into laughter when he realizes his proposed lyric may sound too much like an indictment of our situation.

I laugh, too. After all, for ten minutes, we’ve been debating potential end-rhymes for “sea” in the second verse of our simple three-chord strummer, a short folk song that somehow addresses anxiety with references to chromosomes, mountains, and streams. In his 30-year career, Tweedy has written several generational anthems and made a handful of genre cornerstones; I wrote exactly one love song in college, for a girlfriend I didn’t actually have. So far, our song has engendered an occasionally tedious and awkward process — protracted periods of silence punctuated by listless “umms” and staccato bursts of discarded inspiration. If he’s miserable, I get it.

“That just came out, because, well …” Tweedy trails off behind a wry grin. At 53, Tweedy has grown into his wavy brown hair, salt-and-pepper beard, and square frame like some beloved college professor. He leans into The Loft’s leather couch, adjusts his red face mask, and takes the verse from the top, chin lifted but eyes closed. When it’s done, he laughs again but this time expressing genuine delight, stunned his quip might work.

“That’s a good placeholder if nothing else,” he says. “But I feel like we’re really close.”

Just then, Mark Greenberg — the studio manager and one of two people, alongside engineer Tom Schick, who has met Tweedy at The Loft to work almost every day for the last decade — springs from behind shelves crowded with gig posters, a painting of Batman, and labeled reels of tape from Wilco and Uncle Tupelo, the foundational alt-country band of Tweedy’s early 20s. Greenberg is one of Tweedy’s oldest local friends, himself a multi-instrumentalist, formerly of the inquisitive Chicago institution the Coctails.

A gregarious teddy bear of a man, with a permanent grin still evident even beneath a mask, Greenberg is instantly likable. He beams like a kid flashing his new PS5 when he shows me the customized guitar straps he makes and sells from a dim recess of The Loft. He points out prized pieces of memorabilia — a piano-shaped phone signed by Norah Jones, a Johnny Cash guitar strap, a half-dozen Persian cat ceramic statues from the band’s Star Wars album cover — with a zeal that makes you feel like you’re getting an exclusive tour, though you know he’s done this before. (The Loft’s Topo Chico refrigerator and Tweedy’s matching socks remain peculiar thrills.)

Greenberg guffaws when we tell him that we’ve already got bits of two verses and a chorus. “Throw a goddamn middle eight in, and you’re done!” he exclaims. “Also, 15-minute warning.”

Tweedy suddenly gets very serious. A blue-collar kid from a hardscrabble St. Louis suburb, Tweedy has long embraced an on-the-clock workaday approach to making music, decidedly not romantic, mystical, or precious about it. One of the most critical components of How to Write One Song is his insistence that there’s always time to get something done, no matter how tight the timeframe. In How to Write One Song, Tweedy remembers penning songs in hotel lobbies while waiting on the rest of Wilco; today, in the studio, he tells me about how Wilco recorded a series of still-unreleased improvisational “albums” by jamming for as long as a spool of tape lasted while working on their 2004 bellwether A Ghost Is Born. For Tweedy, practice and habit (and, crucially, putting down your phone) matter as much as meter and melody.

“He’s a workaholic,” Greenberg says later as we amble through The Loft, passing Tweedy’s desk, one piled so high with books and records and St. Louis Cardinals ephemera that barely a sliver of wood is left visible. “And this is his happy place.”

Yet here Tweedy is on a Monday morning with 15 minutes to finish co-writing a song with an absolute amateur — not what I’d call “happy” circumstances. When Greenberg returns, Tweedy waves him off with a trace of impatience, tweaks a few prepositions, adjusts his amphibian-eyed Daniel Johnston baseball cap, and asks if he can sing our words aloud. Greenberg, Schick, and Tweedy’s oldest son, 24-year-old Spencer, gather around and nod along.

“Thank you. That was fun,” Tweedy says, smiling, when he’s done and leans the guitar against the couch. Any residual misery has evaporated in our accomplishment. “There are some lyrics in there I really like — the snow waking up, walking off the trees. That’s a legit song.”

I remind him that I’ve read his book, where everything’s a legit song. His laughter booms: “No, but that’s an especially legit song.”

To any casual-at-best Wilco fan, the impression of Jeff Tweedy might be that he’s one of music’s supreme miserabilists, an architect of mopey “dad-rock” or “sad dad jams.” For years, he could be famously fractious with the press, especially writers wanting to cloister him within his alt-country origins, and hecklers who needled him onstage. As late as 2018, he righteously dressed down an audience member who kept yelling “Kavanaugh” the day before the accused rapist was confirmed to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, his best-known album, 2001’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, opens with a noise-pocked manifesto of existential equivocation called “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart.” Its 2002 namesake documentary captured the record’s fraught making and release; the film hinges on a scene where Tweedy, beleaguered by bickering bandmates, vomits inside a bathroom stall.

Tweedy’s battles with opioids and alcohol have become part of his public history, along with the sense that he spent years somnambulating inside a grumpy haze. “I dreamed about killing you again last night/ and it felt alright to me,” he muttered on 1999’s Summerteeth, then warned five years later: “I’m a wheel/ I will turn on you.” In 2003, after the runaway success of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, Wilco was writing the album that song would appear on, A Ghost Is Born, in The Loft. It was the lowest point of Tweedy’s life, he admits. The album wasn’t a suicide note, per se, but it was intended to give Spencer and Sammy, then toddlers, a portrait to remember their father by when things inevitably, he assumed, ended badly. But Tweedy went to rehab in early 2004 and emerged with a new worry — that all those songs written from an abyss would no longer resonate with him. Instead, he discovered revisiting them that they’d initiated his recovery.

“It’s like the songs were saying, ‘It doesn’t have to be this way, Jeff,’” he reflects on it now, stirred enough by their memory that he nearly sounds out of breath. “They let me work through some idea of salvation that didn’t occur to me until I was out of the hospital. Those songs ended up being notes to myself, about how to reconstruct the better parts of me.”

During the last decade, Tweedy’s better parts have reshaped his public image. He’s emerged as something of a new paragon for the aging indie rock star — philanthropic and accessible, professionally ambitious but personally modest. His response to fame has been uncommon: Tweedy plays music with his sons, Spencer and Sammy, and alongside them and his wife, Susie, has started making charming home movies on Instagram during quarantine; with Wilco, he has launched a music festival at one of the country’s largest art museums (picture the world’s most idiosyncratic summer camp for adults); The Loft is so choked with gear that Wilco auctions a trove of it each year, directing some proceeds to local charities.

His books — particularly his debut memoir, 2018’s Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back) — are disarming case studies in demystifying the cultish shroud of celebrity. He transcribes conversations with Susie that make him sound petty, and he directly addresses the things in his career that would make for a salacious episode of Behind the Music (see: the dissolution of Uncle Tupelo or his sobriety). Likewise, his recent triptych of solo albums captivate because they are so clear and candid in their grappling with the common exigencies of life as an adult regardless of fame. In the centerpiece of Love Is the King, the tender little record Tweedy made with his kids during quarantine, the weary young man who once dreamed about killing you again last night emerges as a gracious husband and father. “If I may have your attention please,” he croons, “I’ll tell you about my wife and what she means to me.”

“There are ways I like to think about myself, childlike things: I want to be a songwriter. I want to be a nice person, a good person,” Tweedy says. “The correlation I made early on is that the only way to get there is by thinking about what activities support that idealism. Like, if you want to think of yourself as a songwriter, write songs.”

That shift stems somewhat, Wilco drummer Glenn Kotche theorizes, from a merger of Tweedy’s private and public personae. His old friend has shed the grouchy character. “I don’t think people leave Wilco shows anymore and say, ‘Man, that guy is disgruntled,” Kotche says. “It’s more about sharing the moment and something that will enrich all our lives, not being stuck in our own heads.” He’s right. The first half-dozen times I’d been in the same room as Tweedy, I avoided making an introduction for fear of his reputation; I imagine that, had I proposed writing a song together during the era of A Ghost Is Born, he would’ve said “fuck off” rather than play along.

Tweedy balks the first time I bring this up, three weeks after we finished our song, on an Election Day where he almost sounds exuberant. He’s always enjoyed talking about music to people who care about it, he rebuts, so he might have been game for such a stunt, even in his narcotized state.

Then, he pauses.

“You know, I wouldn’t have been as able to keep pulling myself back to your involvement,” he says, grunting as if he’s just untangled some difficult knot in his past. “You would have come here, and I would have sat and written a song in front of you. I wouldn’t have been as aware of my surroundings — and that the task was about collaboration.”

It’s impossible not to believe Tweedy owes at least some of his transformation to this one near-daily activity: songwriting. I can say that now, because, occasional impasses notwithstanding, our two-hour rendezvous was as meaningful as most of my previous therapy sessions. A few minutes after we first sit down to get started, when Tweedy hands me the bulky black briefcase where he stuffs the bits of songs he’s written during the last three years, I realize it’s a literal version of life’s emotional baggage. He passes it to me to gauge its heft, joking, “I sell my work by the pound now.”

And then, the exercise begins: Tweedy first asks me to select a hyper-specific noun, whatever’s on my mind. “Parking cop,” I say without hesitation, admitting I’m nervous about the RV I’ve left out front in a metered city space. From there, I offer nine verbs about what a parking cop might do, like “chalk” tires or “negotiate” with irate customers; with a shrug, he adds the tenth: “nap.” He tells me to write down ten unrelated nouns on the other edge of a legal pad, encouraging me to filter as little as possible. There’s a caveat.

“Ideally, you would just let it flow out of you,” he says. “But it’s hard not to make some judgement, because I know what words I wouldn’t want to sing. If an avocado is sitting there, I’m not going to put it down. I can’t imagine myself singing about an avocado.”

My second noun is, naturally, guacamole, surrounded by nine items that scan even to me as entirely arbitrary: mountain, score, shark, chromosome, blanket, and so on. Tweedy welcomes the grammatical ambiguity of some selections, or how several of the nouns also function as verbs. He wants me to lean into that flexibility for the final phase of our word-ladder experiment: a poem, linking the ten verbs and ten nouns.

We both start writing, pausing to swap stories about the British songwriter Bill Fay, whom Tweedy helped coax out of retirement, and the playfulness endemic to certain words. I read him my associative free verse — “I type the chromosome/ sweating into a blanket,” it begins. He follows with a more deliberate creation, its longer lines zigging in and zagging out of rhymes. “Chlorophyll is walking off the trees,” he reads flatly. “Listen how a broken hip speaks.”

We discuss some bits we like and laugh at our attempts to shoehorn guacamole into verse. Tweedy stops smiling, though, the instant I lampoon my own poem, sarcastically calling it “a masterpiece.”

“I know you didn’t mean that, but this is not what I would use for a song,” he says, pausing to finesse his frustration. “This is to remind myself what the possibilities are in language, to disorient myself. This is where bad poets live, because they haven’t translated this language back into something someone else could see. You should aspire to make a connection.”

For the next hour, as we use our little poems to help shape our song, these words do foster a connection. I tell Tweedy about climbing a Teton; he tells me about sliding down a slick snowfield during a hiking trip last Summer with the comedian Nick Offerman and the writer George Saunders in Montana’s Glacier National Park. I tell him about hiking the Appalachian Trail and pain that lingers a year later; he tells me about breaking both his shins while running and his new fitness regimen of long Peloton rides. The conversation slowly shapes our nonsense verses into lines about the Sisyphean effort of doing anything at all — that is, as soon as you begin to enjoy the view from the top of some proverbial mountain, it’s time to climb down and start again. The idea that you’d expend all that energy getting up an obstacle just to reverse course becomes our ironic hook, half-whispered over a sudden walk down the guitar’s neck.

He loves it.

“I’d hear that and go, ‘Did he just say what I think he said?’ There’s all this heroic language just to walk right back down,” he says, chuckling. “That is kind of what life is: You have all these things that seem insurmountable, and instead of going over them, you just survive. Now you just know the way.”

We record the song in a single two-minute take on my iPhone, as Tweedy often does for his own writing exercises. He flubs a line and apologizes; Greenberg jokes about hiding the mistake with pedal steel. I head for my RV, relieved to find no parking ticket.

For the next week, though, my mind drifts back to my nouns and what they were trying to tell me. Some, like shark and chlorophyll, were obvious — I’d watched a contentious episode of Shark Tank while falling asleep in a hotel the night before, and the foliage along the cross-country drive to Chicago that week had wowed me. But others had unintentionally mined one of my deepest worries. An hour before I arrived at The Loft, I learned an old friend had been diagnosed with lymphoma after prolonged leg pain — hence chromosome, hip, and grimace. And in this year of dashed plans and devastating losses, I’ve been unable to travel enough to do my favorite thing in the world: mountain climb.

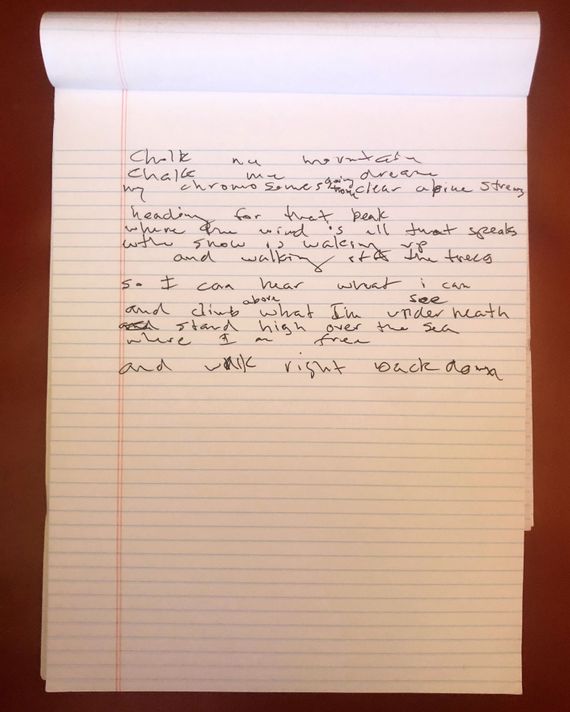

Mountain was the first word on my list, the object that flowed out fastest. Tweedy sensed its importance and instinctively began singing a bit from my poem — “and I chalk up a mountain” — massaging it into a draft of our song’s first few lines: “I’m chalking up my mountain/ I’m chalking up my dreams / Knowing that the world isn’t always as it seems.” No, they’re not profound at all, but, at this point in 2020, that rhyme articulates my confusion and exhaustion in a way that feels restorative. I’ve found myself humming the bit ever since like a little mantra I helped make.

I tell Tweedy on Election Day about my breakthrough. He knows the feeling well. The process reminds him of the first time he saw a glacial lake while hiking through the mountains of Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. If he stared at the water, it looked colorless and inconsequential; when he titled his head slightly, though, it radiated a pale indigo. He arrives at similar clarity through writing. He tells me he listens to his own songs, too, in part because they reaffirm those moments of crystallized awareness.

“The things that help me the most are not feeling associated with songs that people love or have gotten a good review,” Tweedy says. “It’s the feeling that I was able to unburden myself for some period of time and make something that wasn’t there before.”