It takes only a thought exercise to realize how central certain performances are to Quentin Tarantino’s films. Imagine, if you can, what key parts might have looked like if someone else had played them: Daniel Day-Lewis as Vincent Vega in Pulp Fiction instead of John Travolta. Kill Bill with Warren Beatty as Bill instead of David Carradine. Leonardo DiCaprio as Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds instead of Christoph Waltz. Jennifer Lawrence as Daisy Domergue in The Hateful Eight instead of Jennifer Jason Leigh. All might have been great, but casting them would have changed the films on a genetic level.

Though filled with action and dynamic set pieces, Tarantino’s movies are driven by their characters, and the director loves to give his cast room in which to work. He writes scripts filled with distinctive dialogue that sounds like it was written with the actors in mind (and sometimes it is). Consider the famous faux-biblical passage of Ezekiel 25:17 from Pulp Fiction. Sure, to paraphrase Samuel L. Jackson’s Jules Winnfield, it sounds like some cold-blooded shit to say to a motherfucker before one pops a cap in his ass. But it’s Jackson’s cadence, and the look in his eyes, that makes the scene unforgettable.

Tarantino has a habit of working with the same actors again and again with good reason: They do great work for him. But that stock-company approach has forced us to lay down some ground rules for this list of his films’ greatest performances — no actor appears here more than once. That doesn’t mean, say, that Jackson isn’t great in Jackie Brown (he is) but that the list chooses to honor an even more remarkable performance. Also we’re counting Kill Bill as one film because Tarantino does; that’s a debatable point, but that debate can rage somewhere else.

With that out of the way, let’s start, appropriately enough, where it all began.

20. Quentin Tarantino as Mr. Brown, Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Tarantino once thought acting would be a bigger part of his professional portfolio. He studied at the James Best Theatre Company, a school run by the esteemed character actor now best known for playing the incompetent Roscoe P. Coltrane on The Dukes of Hazzard, and can be seen as an Elvis impersonator in an episode of The Golden Girls. After breaking through, he cast himself in a key role in Pulp Fiction, co-starred with George Clooney in From Dusk ’Til Dawn (which he scripted), appeared in the little-loved Destiny Turns on the Radio, and even tried his hand at Broadway opposite Marisa Tomei in a 1998 revival of Wait Until Dark.

The only problem: Tarantino’s acting work was met with less praise than his work as a writer and director. His one undeniably great moment in one of his own films, however, occurs in the opening scene of his debut, Reservoir Dogs, in which his Mr. Brown offers a radical reinterpretation of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin.” It set the table not just for the rest of Reservoir Dogs but for all the films that followed. Tarantino’s work acknowledges the pop-culture sources that inspire it — from Jean-Luc Godard to half-forgotten ’70s TV shows — while offering a charged reinterpretation of them. In interviews, Tarantino has long been a vocal, passionate advocate for these sources, framing his appreciation with his own personal takes on what they mean. Similarly, the “Like a Virgin” monologue establishes the profane world of the film while doubling as a mission statement for the filmmaker delivering it: What you’re about to see may look familiar, be it a gangster film, a World War II action movie, or a Western, but don’t expect it to work in the ways you’ve grown accustomed to.

19. Zoë Bell as Zoë Bell, Death Proof (2007)

It’s not all about words in Tarantino movies, however. Inspired by her work as Uma Thurman’s stunt double on the Kill Bill films, Tarantino cast Zoë Bell as one of the stars of Death Proof, his contribution to the double-feature Grindhouse, an homage to the low-budget exploitation films of his youth. (Robert Rodriguez directed Planet Terror, the other half of the double bill, which also includes trailers for nonexistent features directed by Rob Zombie, Edgar Wright, and Eli Roth.) Death Proof begins as a nod to slasher movies but ends as a turbocharged chase movie in which a group of women exact revenge on a misogynistic villain, a stuntman who drives specially rigged “death-proof” cars. (More on him below.) Playing herself as a cheerful, game-for-anything daredevil shooting a movie in rural Tennessee, Bell stages a “ship’s mast” stunt (strapping herself to the hood of a fast-moving 1970 Dodge Challenger) and performs what could happen when that stunt goes horribly awry. It’s jaw-dropping physical work, but Bell’s charming performance between action sequences is what makes her Death Proof role so winning. She stares death in the face with a puckish smile.

18. Walton Goggins as Chris Mannix, The Hateful Eight (2015)

Some actors were seemingly born to appear in Tarantino films. Among that company is Walton Goggins, who had kicked around Hollywood for years before breaking out with back-to-back runs on The Shield and Justified. Adapted from a story by Elmore Leonard, one of Tarantino’s primary influences, the latter series found Goggins lending a sometimes psychotic intensity to precisely phrased repartee. When Tarantino came calling for his Western whodunit The Hateful Eight, Goggins (who’d previously appeared in Django Unchained) was more than ready to play another charismatic but morally suspect character, and the result is one of the film’s standout performances. Goggins plays Chris Mannix, a former Confederate sympathizer who claims to be on his way to become sheriff of the town of Red Rock. Like everyone in the film, he’s a slippery, largely despicable person who may or may not be telling the truth. (Goggins has said Tarantino asked him to decide for himself and then never tell him his choice.) But if there’s any glimmer of hope in Tarantino’s darkest, most despairing film, it comes in the final moments, when Mannix and Samuel L. Jackson’s Major Marquis Warren seem to reach some kind of mutual understanding about the promise of America — even if they know that promise is based on a lie.

17. Jennifer Jason Leigh as Daisy Domergue, The Hateful Eight (2015)

The Hateful Eight takes its title seriously. The film invites no sympathy for any of its characters, nor do any of them expect sympathy from those around them. Daisy Domergue, a fugitive handcuffed to Kurt Russell’s imposing bounty hunter, John Ruth, might have looked helpless if played by an actress other than Jennifer Jason Leigh. But Leigh pushes back when pushed, or worse, by John and the others. It doesn’t make the scenes of violence against her any less uncomfortable, but The Hateful Eight doesn’t try to traffic in comfort. In a film filled with nasty characters, she’s as nasty as any, and Leigh plays her without any suggestion of softness. The world beat that out of her long ago.

16. Jamie Foxx as Django Freeman, Django Unchained (2012)

From Kill Bill though The Hateful Eight, Tarantino has spent much of the 21st century so far making films that consider the implications and complications of taking revenge. The story of a former slave who takes no pity on a southern plantation while attempting to rescue his wife, Django Unchained might’ve played as a simple fantasy of getting even if Jamie Foxx hadn’t captured the fullness of Django’s journey: He begins the film in debased circumstances and ends it as an action hero. Foxx makes every step of that transformation register as he recovers the humanity and respect denied him since birth and leaves the system that denied it to him in flames.

15. Kurt Russell as Stuntman Mike McKay, Death Proof (2007)

A scarred stuntman who spent his glory days working on TV shows no one remembers, Mike now spends his time stalking and killing women via a specially outfitted car. He’s a character who hates women in the middle of a film that at least begins as an homage to slasher films — a genre that often seems to hate women too. But Death Proof flips the script on the genre’s tropes, and Mike, and Kurt Russell’s performance, rolls with the changes. In early scenes, Mike is all oily menace. By film’s end, he is reduced to a pathetic heap of a man, and Russell hasn’t so much recalibrated his performance as let the changing context cast his character in a different light. It’s deft, egoless work exposing the seedy underside of a whole class of big-screen tough guys before laying them to rest for good.

14. David Carradine as Bill, Kill Bill (2003, 2004)

If you make a two-part film called Kill Bill in which the lead character spends much of the running time trying to track down and kill an initially unseen man named Bill, Bill himself had better not disappoint when he finally shows up. Tarantino chose well in casting David Carradine, a ’70s icon more likely to be seen at the time in films like Children of the Corn V: Fields of Terror than in a highly anticipated film from a name-brand director. Carradine brings a relaxed charm to his role, greeting Uma Thurman’s Bride like an old friend when she finally catches up with him but not quite masking his sinister side as they reunite. He both embodies the role of a villainous mastermind and subverts viewers’ expectations of how a villainous mastermind ought to look and act. In other words, he’s the perfect Big Bad for Tarantino’s most ambitious film.

13. Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

Listen, this is going to be divisive. Some of the early press about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood focused on how few lines Margot Robbie had as Sharon Tate, the most famous victim of the Manson Family, compared with the characters played by Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt. Yet the performance itself exemplifies how much more presence can matter than words. In her most memorable scene, Tate decides to check out a matinee of The Wrecking Crew, in which she plays klutzy comic relief opposite Dean Martin’s Matt Helm. After shyly revealing her identity to the ticket taker and manager, she slips on a pair of glasses, props up her feet (it’s a Tarantino movie, after all), and watches herself on the screen, relaxing only after the audience around her responds warmly to her performance. Without a word, Robbie conveys the vulnerability, insecurity, and satisfaction that are intrinsic to acting, and her warm, earnest interpretation of Tate doubles as an elegy for a woman who never got a chance to fulfill her early promise. (And just imagine what Robbie could’ve done with words.)

12. Harvey Keitel as Mr. White, Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Tarantino’s career wouldn’t exist as we know it if the screenplay for Reservoir Dogs hadn’t ended up in Harvey Keitel’s hands. After Keitel signed on as co-producer, Tarantino abandoned his plans to shoot the film on a minuscule budget and started to look beyond his circle of friends for the cast. Reservoir Dogs arrived at a point in Keitel’s career when he was seeking out projects from independent filmmakers in which he could deliver daring work. (See also: Bad Lieutenant, The Piano, and so on.) He makes Mr. White the most sympathetic of the movie’s crooks, a man who lives by a kind of code of honor and develops real compassion and deep concern for Tim Roth’s Mr. Orange when he is injured in the line of duty. In the film’s final moments, Keitel gets an unforgettable moment when he realizes how that compassion and concern have sealed his fate.

11. Tim Roth as Mr. Orange, Reservoir Dogs (1992)

As the other half of the Mr. White–Mr. Orange double act, Tim Roth plays the first of many Tarantino characters to put their lives in jeopardy by assuming another identity in pursuit of a loftier goal. An undercover cop posing as a criminal, Mr. Orange lets doubt creep in only when he’s alone but then immediately sets about psyching himself up for the job at hand. In one of the film’s most stunning passages, he rehearses the killer anecdote that will ensure he passes as a criminal. He slips into character, memorizes the story, and finds new nuances to the tale until no one can doubt it. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the sequence serves as a stand-in for the ways an actor prepares for a role. Mr. Orange is also the film’s emotional heart, a virtuous character in a world that punishes virtue and in which values like loyalty and empathy can prove fatal.

10. Brad Pitt as Aldo “the Apache” Raine, Inglourious Basterds (2009)

To play a tough guy in the Lee Marvin mold, one who could convincingly command a band of fierce Jewish soldiers sent to cause trouble behind enemy lines, Tarantino turned to Brad Pitt, an actor who could weave notes of knowing humor into his performance without losing the menace. Demanding, with a Smoky Mountains twang, that his men bring him “one hundred Nat-zee scalps” and delivering lines like “And through our cruelty, they will know who we are,” he is dead serious. But Pitt knows how to play the moment for black comedy, capturing the weary yet determined attitude of a man who has been fighting Nat-zees so long he can’t remember how to do anything else.

9. Mélanie Laurent as Shosanna Dreyfus, a.k.a. Emmanuelle Mimieux, Inglourious Basterds (2009)

In a film whose unexpected finale casts everything that has come before it in a new light, Inglourious Basterds’ final moments can be interpreted as an attempt to overwhelm history with film and fantasy. But by then, it has already established itself as a movie about performance, the craft of acting, and the extremes we go to to reinvent ourselves in order to survive — abiding Tarantino themes. That’s true of the American and British heroes who go undercover to infiltrate the Nazis with varying degrees of success and of “Emmanuelle Mimieux,” actually Shosanna Dreyfus, the sole survivor of a Jewish family massacred in the film’s opening scene. Hiding under an assumed identity in Paris, where she has taken a job at a movie theater, she seizes the chance to use film itself to exact revenge on those responsible for her family’s deaths. Mélanie Laurent plays the role with a mask of cool under the most trying of circumstances, until the chilling moment she lets the mask slip.

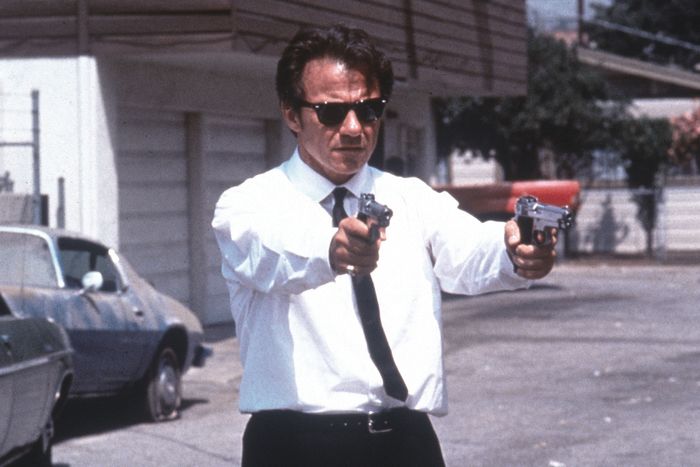

8. Michael Madsen as Vic Vega, a.k.a. Mr. Blonde, Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Reservoir Dogs never lets viewers know where they stand. It asks its audience to get to know, and in some ways root for, a bunch of colorful criminals, then provides almost offhand reminders that these are not nice guys — they’re desperate, violent men willing to sacrifice anyone standing in the way of their goals. Some, however, are less nice than others. Michael Madsen brings a casual sadism to his work as Mr. Blonde, sipping a soda and grooving to “Stuck in the Middle With You” as he prepares to mutilate a policeman bound to a chair. He gives Reservoir Dogs its most unforgettable moment, pausing to vamp before committing horrific acts that threaten to turn Tarantino’s debut into into a horror movie. The scene’s almost impossible to watch, in part because Mr. Blonde treats it like just another day at the office, one in which he has to find creative ways to pass the time to keep from getting bored.

7. John Travolta as Vincent Vega, Pulp Fiction (1994)

Pulp Fiction offered John Travolta a way in from the wilderness of films like the Look Who’s Talking series, but part of what makes his performance so remarkable is how he works as if he doesn’t even need a comeback. Travolta carries himself with the assurance of a movie star, one who expects viewers to stay interested in his mob-enforcer character as he goes on about French Quarter Pounders and arrives for a night out with his boss’s wife almost too drugged out to notice the chemistry that’s developing between them. It’s the sort of role that could die on the screen without a charismatic performance driving it, one that could even stir sympathy for a man in the habit of never quite recognizing his mistakes, or the damage he causes, until it’s just a little too late.

6. Christoph Waltz as Hans Landa, Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Some actors seem threatening when they scowl or grimace. As the SS officer Hans Landa, Christoph Waltz never seems more dangerous than when he smiles. Waltz, who was virtually unknown out of German-speaking countries when Tarantino cast him, grins his way through the movie, from the farmhouse interrogation of the opening scenes to (almost) the very end. In some ways, Landa serves as the flip side of Brad Pitt’s Aldo Raine. He’s terrifying but also often upsettingly funny, as if he has passed beyond caring about the implications of his actions and now wants to entertain himself as he tortures his prey.

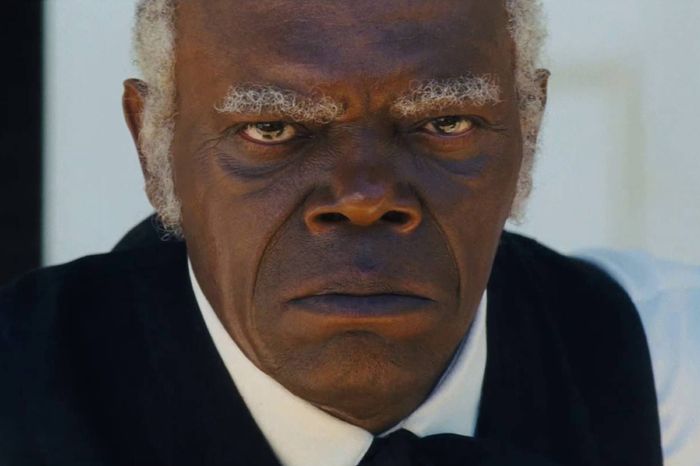

5. Samuel L. Jackson as Stephen, Django Unchained (2012)

Samuel L. Jackson has done remarkable work in Tarantino’s films since his Jules Winnfield emerged as the unlikely moral center of the seemingly amoral universe of Pulp Fiction. For Django Unchained, he took on the daunting role of a slave who has found it beneficial to align himself with his sadistic master (Leonardo DiCaprio) and is determined to do whatever it takes to hold on to the privileges he is granted by betraying his fellow slaves. It’s a high-wire act, and Jackson brings layers of complexity to his work, suggesting Stephen’s tortured psyche while doing nothing to soft sell his venality and cruelty. He’s an Uncle Tom trope reborn as a monster.

4. Leonardo DiCaprio as Rick Dalton, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

Tarantino has created stories about men hitting the limits of their chosen professions — and the identities they’ve built around those professions — since Reservoir Dogs but never as explicitly as in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. The film features Leonardo DiCaprio as Rick Dalton, a former star of TV Westerns who finds himself struggling as the ’60s draw to a close. Dalton swims in regret and alcohol and sputters nervously when talking to an agent who may know how to pull him out of his slump (or may just be trying to exploit him for a quick buck). But Dalton can still summon the old fire, even if he’s now reduced to playing the guest heavy on others’ shows. DiCaprio lets Dalton teeter between the pull of his innate talent and the destructive doubt stirred by an industry in the habit of discarding stars once they’ve outlived their usefulness. The professional travails of a cowboy actor might not seem all that consequential, but DiCaprio makes every shift in emotion register and every breakdown seem like a crisis from which he might never recover.

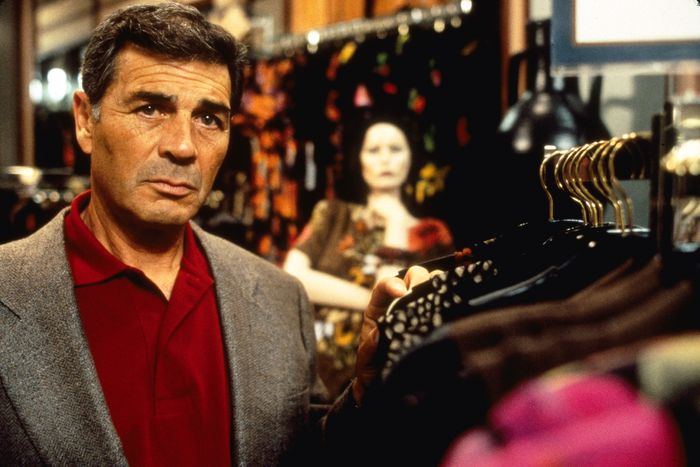

2. Tie: Robert Forster as Max Cherry & Pam Grier as Jackie Brown, Jackie Brown (1997)

After resuscitating John Travolta’s career, Tarantino turned to two of his favorite actors from the ’70s for his Pulp Fiction follow-up, an adaptation of the Elmore Leonard novel Rum Punch. Both roles draw on the actors’ pasts, Robert Forster’s as an intelligent tough guy and Pam Grier’s as a blaxploitation icon. But it’s the slowly developed, unexpected middle-age romance between Forster’s bail bondsman, Max Cherry, and Grier’s small-time smuggler, Jackie Brown, that powers the film. The plot zips along, but the real show here comes from Max shopping for Delfonics albums to keep the vibe of hanging out with Jackie going, and from Jackie awakening to second chances she never imagined might be available to her. Separately, they both deliver career-redefining performances. Together, they create an unforgettable, if bittersweet, love story in the midst of a twisty crime thriller that repeatedly threatens to tear them apart.

1. Uma Thurman as the Bride, Kill Bill (2003, 2004)

Consider this: Not only was the lead role of Tarantino’s two-part revenge thriller physically demanding (and unnecessarily dangerous thanks to some tough-to-forgive negligence on Tarantino’s part), it required constant recalibration. Over the course of Kill Bill’s two volumes, which pay tribute to a cornucopia of Tarantino’s cinematic obsessions, Uma Thurman’s revenge-seeking Bride appears in a Japanese gangster thriller, a grungy ’70s horror movie, a kung-fu film, and several other genres. She has to keep her character consistent as the film around her is constantly changing form (almost like Buster Keaton when he steps through the movie screen in Sherlock Jr.). She has to fight her way out of danger in seemingly half the film’s scenes and suggest an inner life with complications that extend beyond her bloody-minded quest for vengeance. And finally, she has to hold back just enough that the film’s last moments, arriving after a cumulative running time longer than Gone With the Wind’s, still pack an emotional wallop — which she does, and then some. It is masterful work, the performance of a lifetime, delivered in the midst of a film whose director seems determined to try all the tricks he can imagine and expects his star to keep up every step of the way. If anything, Thurman outpaces him.