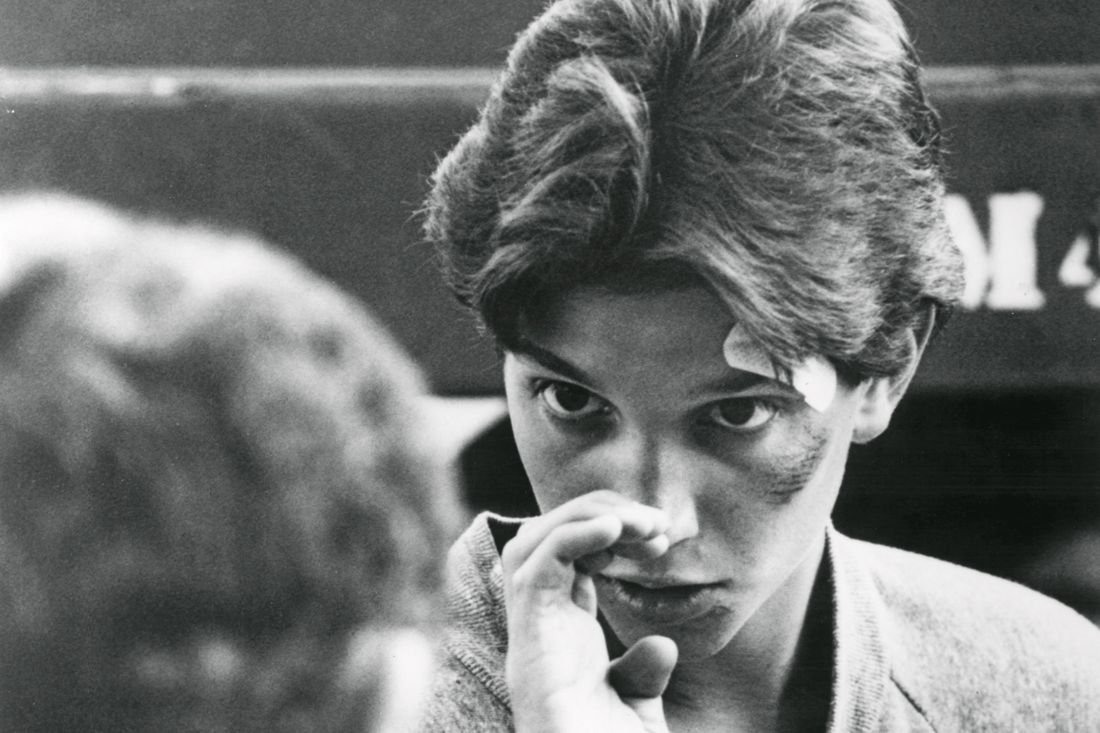

When a fresh-faced young actor from Long Island named Ralph Macchio auditioned for the lead role in The Karate Kid in 1983, he couldn’t have known the sensation it would become. In the almost 40 years since, John G. Avildsen’s blockbuster has led to three sequels, an animated series, a remake, a planned Broadway musical adaptation, and, perhaps most impressive, a revival TV series featuring most of the original cast. But back in 1984, there was just this one movie — and based on the rapturous response that greeted the real-life Daniel LaRusso after the first preview screening before The Karate Kid’s release, it was destined to be big.

The story of that fateful screening is one of the many heartwarming and simple yet insightful anecdotes featured in Macchio’s new memoir, Waxing On: The Karate Kid and Me. The book provides a thorough account of the casting, production, release, and aftermath of Macchio’s most famous movie, but it’s told with a light touch and a narratorial voice that feels like hearing a story from a friend. For every juicy bit of behind-the-scenes lore — the origin story of the famous crane kick, for example — there’s a subtle, touching reflection on what this character and these performers have meant to Macchio over the years. Particularly moving are the stories about the bond he developed with the late Pat Morita, whose experience as a comedic actor couldn’t have prepared anyone for how iconic his portrayal of Mr. Miyagi would become.

In the excerpt below (which has been slightly edited from the book version), Macchio muses on the decade that birthed the first three Karate Kid movies and changed everything for him. There’s a powerful American nostalgia for pop filmmaking of the ’80s, a nostalgia that helped make the Karate Kid Netflix follow-up, Cobra Kai, such a success today. (Its fifth season dropped last month, adding The Karate Kid Part III’s Sean Kanan and Robyn Lively to the series’ stable of returning performers.) Perhaps there’s something a bit naïve about indulging in the black-and-white, good-versus-evil morality of some of those hits — yet they still stick with us many years later because of their style and, above all, sincerity. In describing his own journey to find balance in his performances and life, Macchio’s memoir achieves the same result.

EXCERPT FROM 'WAXING ON: THE KARATE KID AND ME'

One of the things I hear most when fans reference Cobra Kai on Netflix is how much they love the nostalgia that is woven into the series, the undeniable homage to the ’80s. That movie era has become a favorite for so many. The music. The dating scenes. The heroes and villains. The training montages. Not to mention the big hair and the mismatched outfits. Who can forget LaRusso in his camouflage pants and tucked-in plaid shirt? No belt, of course.

When I am asked what I remember most about the ’80s — the outfits, the music, the movies, the fads, the TV shows, or the catchphrases — I really don’t come back with a quick answer or one that is particularly well versed on the era. For me, at the time, I was on the outside of it. Or, more accurately, on the way-way inside of it. I find it funny and notable that I have less knowledge of that time period than most. I was fairly out of touch about what was cool or trendy, as I was honestly living in a bubble. My experience was different from that of those who were out and about. I was kind of going from movie set to movie set during those years. And when I was on location and not filming, I was in either my rented apartment or my hotel room, prepping for my next day of work. I remember Rob Lowe joking that I should have a T-shirt that said “Do Not Disturb” on the front. That was often the sign on my hotel-room doorknob during The Outsiders. And up to that point, when I wasn’t working, I was usually back home on Long Island, lying pretty low there as well. Perhaps that’s why I never got sucked into all the partying and the drugs that were flowing so freely during that era (an observation that I circle back to later in the book). After all, I never got a Brat Pack membership card or even an invitation to join. So what do I really know about the ’80s of it all? That being said, Daniel LaRusso is a Chia Pet these days, so I must know something about the era. Even if I was never asked to be in a John Hughes movie. Though, I did get close once.

It was after the filming of The Outsiders. I was in Los Angeles. At that time, Emilio Estevez and I would hang out on occasion. I even stayed over at his house once or twice, as it was in the Malibu area and it was a pretty long drive back to whatever hotel I might have been staying at. I recall at least once staying in his brother Charlie [Sheen]’s room when he was either out of town or out for the night. This was in late ’82 or early ’83 and before The Karate Kid happened. I remember both Emilio’s agent and my agent securing us each appointment times to audition for John Hughes for his new Universal Pictures coming-of-age movie Sixteen Candles. Emilio was to audition for the studly handsome guy, and I was being seen for the geeky-nerd kid. I’m a little unclear on whether it was his idea, mine, or both, but we thought it would be cool to audition together. This is something that is not customary on the first round. The casting folks and directors usually like to focus on one actor at a time and then in further audition rounds they might bring people together for a chemistry read. But I think since Mr. Hughes and the casting team knew that Emilio and I had just completed a film together, they allowed us to come in and read at the same time. As a side note, the previous year, Francis Ford Coppola had had a lot of us actors reading and auditioning together for The Outsiders. Perhaps that info had traveled around town in Hollywood and it became something more openly accepted at the outset in casting sessions. In any event, Emilio and I were granted approval to go to the Universal Studios lot and tag-team our presentation of the audition material for John Hughes’s Sixteen Candles.

We didn’t receive any specific coaching or instructions. We only had the general breakdown of the characters and probably the latest draft of the script. He and I just sort of worked out our own version of the scene and added our own blocking and interpretations. Since it was laced with teen antics and comedy, we were looking to highlight the jokes. I came up with a certain nerdy walk for the character and a geeky nasal voice that I chose to speak with. I felt pretty confident, if not cocky, going in, and it took the edge off any nerves having a fellow ex-greaser alongside me. But needless to say, neither of us got our respective parts. The one thing I do recall most vividly is that after each take, Mr. Hughes would make an attempt to instruct me to dial down the character-y-ness a bit. I would say to myself, But this guy is a super-nerd, a total geek. I have to layer that on at least a little bit. Then, after my second failed attempt to win him over, the casting director took me aside and walked me out of the room. He instructed me to take a minute, come back in as myself, and read the scene simply. I recall the words “We just want natural Ralph — that would be perfect. You don’t need to put any spin on it.”

Nevertheless, my final attempt was still unsuccessful in stripping away the nerd-play that I was determined to infuse into this audition piece. Clearly, I didn’t take the direction fully to heart, or maybe, just maybe (and more likely), it bruised my ego to hear that I could be convincing as this geek without even trying. Yep, that was it. I was too cool in my own mind. I have always found this story amusing in retrospect and wondered whether that indeed is what killed any chance for me to ever have an opportunity to work in a John Hughes movie. I doubt that is really the case, but it still makes me wonder what if. I shared the story with Anthony Michael Hall (who won the role, which launched his career) decades later at a Comic-Con event, and we had a good laugh about it. It’s interesting to look back years later and reminisce about how it all came to be. One thing has always seemed clear to me with casting, at least when a movie succeeds like Sixteen Candles did: The right actor undoubtedly gets the right part.

In the fall of ’84, I had what you would call an A-list meeting with a pair of Hollywood heavyweights. I was very excited about the opportunity. The Karate Kid was the talk of the town when I sat down with Steven Spielberg and Robert Zemeckis to discuss their new “time traveler” movie.

The three of us met in a New York City hotel suite. It was not a reading audition, meaning I didn’t have to perform a scene, even though the script for Back to the Future had been sent to me before I sat down with Mr. Zemeckis and Mr. Spielberg. They must have been thinking of me as a potential Marty McFly. The meeting and conversation were fast-paced, upbeat, and positive. I had met Spielberg a few years earlier when he was casting E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Having that experience helped make the conversation more relaxed. I distinctly remember two points that were hit upon during the Back to the Future meeting.

One was the importance of an all-American quality to the character, as was written in the script. The concern was that I had a New York accent that would need to be curbed and a distinct East Coast ethnicity. McFly was apple pie, and as I mentioned in chapter three of this book, I came up more cannoli. From that point on during the encounter, I did my best to try to cover my New York–ness and be optimistic that I could shed the accent and seem more mainstream mid-America. I didn’t have a real read on whether this was effective in the moment, but, still, I attempted to enunciate and slow down my speech cadence. I would love to have video playback of what I was doing. I imagine it came off as a hilarious train wreck.

The other exchange I remember from the meeting is when they asked me whether I was bumped by the boy’s infatuation with his own mother. Did I feel it was an incestuous problem that audiences would have an issue with? I wish I could say that I had an insightful answer, but I believe I just tap-danced around it and expressed my view that as long as it was entertaining, it should be okay. Not my most brilliant response, but at the time it was met with pleasant nods from the two legendary filmmakers.

***

At the moment when the Zemeckis-Spielberg meeting occurred, I had received the confirmation that a Karate Kid sequel production was to happen in the summer of ’85. I was beginning to start my preparation work for Crossroads (slated for spring ’85) and was studying blues, rock, and classical guitar. I was creatively obsessed with the music and the origin of the blues and its influence on rock and roll. I was excited to make that film and explore those roots. The director was Walter Hill, who had made The Warriors and 48 Hrs., two very popular films that made an impression on me growing up. I had already heard that the team for Back to the Future was unsure whether I was the right fit and would not be making a direct offer. They would, however, be open to having me screen-test for the McFly role along with some other candidates. That test deal would include multiple sequel options, similar to the Karate Kid test agreement. Typical Hollywood politics came into play, with one franchise being at Columbia Pictures and the other at Universal Studios, and, in short, the Back to the Future discussions didn’t go any further.

The wonderful irony to all of this is that the all-American, apple-pie role of Marty McFly was eventually awarded to the perfectly cast, but Canadian, Michael J. Fox. And this was after the role was initially given to Eric Stoltz (a wonderful actor whom I later worked with in the early ’90s on a film titled Naked in New York). At the end of the day, whether it’s Molly Ringwald in Pretty in Pink, Matthew Broderick in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Michael J. Fox in Back to the Future, or, dare I be this bold, Ralph Macchio in The Karate Kid — I said it before, and I’ll say it again … the right actor got the right part.

Now, what is it about ’80s movies that makes them so beloved? And where does The Karate Kid sit in the landscape? Well, for one, it seemed to be a simpler time. Or less sensitive. I’m not making a judgment as much as an observation. Everything was way less politically correct. I think that is what audiences find so refreshing about the writing of adult Johnny Lawrence in Cobra Kai. The Zabka character is stuck in an ’80s mind-set with no filter. It becomes entertaining to hear him rattle off what is considered offensive now but was the norm for 1984. Audiences love that element in the writing of the series. He gets away with it because he doesn’t know any better and it reads as innocent. When we rewatch the films of that time period, the viewpoints could be interpreted as dated, to say the least. Yet in many cases, they were hopeful — not as dark as much of today’s programming. Back then, teen angst would often turn to wish fulfillment. Ferris lip-syncing “Twist and Shout” on a parade float down Michigan Avenue. McFly rocking “Johnny B. Goode” on his parents’ prom night. Even the stereotypes were embraced. Take The Breakfast Club, for example. The jock, the nerd, the princess, etc. The Karate Kid had a bit of that as well. The bully, the rich girl, the evil teacher, the wise mentor. It was good-over-evil storytelling. Not too many gray areas, if any. But the audiences loved it, and they still do. Despite being dated, many of these movies hold up because of their timeless themes and aspirational qualities.

Perhaps that’s why parents share ’80s films with their kids seemingly more than films from any other era of movies. They are entertaining and life-affirming. And maybe they provide a bit of escapism from all of the negativity today’s generation is subjected to with the world’s troubles at their fingertips. It becomes family viewing, tying together yesterday and today. The relatability factor of The Karate Kid still feels genuine and current in terms of the bullying and fish-out-of-water scenarios. Despite the ’80s of it all, the themes and messaging remain relevant and strong.

From Waxing On: The Karate Kid and Me, by Ralph Macchio, published today by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2022 by Ralph Macchio