Released in 1972, Frank Perry’s Play It As It Lays is a portrait of modern ennui that hasn’t really lost any of its bite in the intervening 53 years. Which is intriguing, because the picture, adapted by John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion from Didion’s own acclaimed 1970 novel, does feel very much of its era. It’s about a beautiful actress’s fraying psychology in the Hollywood of the late 1960s and early ’70s, and it has a fragmented, pop-art sensibility. (Perry even employed Roy Lichtenstein as a visual consultant.) The film’s signature image is that of its protagonist, Maria Wyeth (Tuesday Weld), driving along the highways of Greater Los Angeles in her bright-yellow Corvette, the arteries and cloverleaf intersections all helping create the impression of someone going around in circles. Meanwhile, flashes of signs and fleeting memories — and, sometimes, ink-blot tests and medical questionnaires and test-answer forms — interrupt Maria’s reveries. She tells us early on that she’s been institutionalized, as she walks along the pleasant paths of a large verdant garden. And although Play It As It Lays proceeds to give us a rough timeline of the events leading up to her committal, it also presents a world in which Maria’s behavior isn’t all that different from everyone else around her. Filtered through her consciousness (which is, of course, also the film’s consciousness), pretty much all of Hollywood is an asylum.

But it’s a lovely asylum, too, and the au courant hollowness of the world Perry presents now has a certain mid-century charm. We sense the emptiness, but when we look at it from the cacophonous anguish of our present, we might also long for it, at least a little. That wasn’t necessarily unintentional; Perry had a way with atmosphere. He made the existential wasteland of suburban Connecticut irresistibly lush in the otherwise bleak Burt Lancaster vehicle The Swimmer (1968), and his devastating teen psychodrama Last Summer (1969) is shot through with the balmy glow of a soft childhood memory harboring a toxic secret. Play It As It Lays wasn’t a huge hit when it came out, and over the years it’s been relatively difficult to see. This new 4K restoration and theatrical rerelease (it’s playing at New York’s Film Forum and will hopefully make its way across the country soon) provides a welcome opportunity to bask in its beautiful blank oblivion.

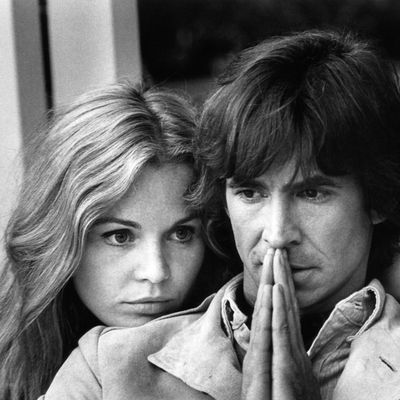

It also offers a chance to catch up with one of Anthony Perkins’s greatest performances. The star of Psycho, who turned 40 right as Play It As It Lays was coming out, here plays B.Z., the producing partner of Maria’s director husband, Carter Lang (Adam Roarke). A far cry from the gawky and boyish Norman Bates, B.Z. is a floppy-haired, closeted Hollywood player slowly dissolving in his own nihilism. Trapped in a sham marriage and unable to ever really be himself, B.Z. responds to his personal despair with cheerful, devil-may-care snark. This makes him a fun hang — he and Maria share a cruel, catty bonhomie — but it also hints at a deeply hurting soul. Maria, who had a hard childhood and lost her parents at a young age, doesn’t initially seem quite so defeated as B.Z., in part because she’s developed tougher skin.

Despite the light framing device, the episodic narrative of Play It As It Lays is largely linear. But Perry edits it as if it were a spiraling fever dream, filled with ellipses and repetition and missing story details. Maria’s emotional deflections work their way into the very form of the film. When she’s forced to have an illegal abortion (Roe v. Wade was still one year away), the whole thing occurs in less than a minute, via a series of elliptical jump cuts. A sexual dalliance with a hunky TV star takes up about 15 seconds of screen time, just long enough to see the guy crack a popper under his nose before he climaxes. A glimpse of Maria and Carter’s official divorce proceeding is even shorter. When she shows up at his film set later, we might wonder if we’re watching a flashback. No, it’s just that even the marriage she’s gotten out of, she can’t seem to get out of. Time keeps turning on itself. Dialogue drifts in from offscreen sources, voice messages, phone calls. Is Maria’s narration an internal monologue, or a confession — and if so, to whom? The whirligig pace of Perry’s cutting, with its constant sense of avoidance, actually represents something of a departure from the novel, which for all its elliptical qualities also refers constantly to Maria’s crying. The book drills down on emotional details in a way the film consciously tries not to; we don’t see her tear up once in the picture. When we see her in close-up, she often stares distantly back at us — a gorgeous, big-eyed void. Play It As It Lays is a cool movie, in just about all senses of the word, and that’s what makes it so powerful. We can project our own anxieties into its emptiness.

Today, the film is mostly associated with Didion — surely the biggest name among the key figures involved — but it’s worth looking at it within Perry’s oeuvre as well. The director had emerged about a decade earlier, through a series of unusually expressive, independently produced movies he made with his then-wife, the screenwriter Eleanor Perry. They were a true partnership: Frank had come from the theater and understood how to handle actors, while Eleanor had a degree in psychiatric social work and understood how to present the most delicate of emotions. The films they made together — including David and Lisa (1962), Ladybug Ladybug (1963), The Swimmer, Last Summer, and Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970) — are filled with both children’s games and portraits of extreme personalities. Their work fit right in with the era’s fascination with psychoanalysis and mental illness. But for all their independence, their films also had classical cohesion. They weren’t stylistically daring, which is probably why they were talked about less and less as the New Hollywood of the 1970s forged on.

Frank and Eleanor divorced a little before he began working on Play It As It Lays, which might help explain why this, among all of Frank’s efforts, is the most stylized, the one that seems most indebted to the formal experimentations of the 1960s. It might also explain, to some extent, the pointed evasions at the heart of the picture, the characters’ almost pathological inability to slow down and take account of life’s wreckage.

Years later, Eleanor wrote an acerbic and wildly entertaining roman à clef, Blue Pages, about her life with Frank and their separation; though it’s very different stylistically from Didion’s novel, at times Eleanor’s book reads not unlike a variation on Play It As It Lays. It certainly suggests that Frank knew a thing or two about the brutality of Hollywood marriages and separations, and the way women were cast off in this world. That might shed some light on the film’s disjointed narrative and freewheeling style. The telling avoidance at the heart of the movie — the protagonist’s refusal to confront the emotional devastation of her life head on — exists both in front of and behind the camera. It’s an essential picture.