After all the reports of sexual misconduct, his trial, and the overturning last year of his conviction on three counts of aggravated indecent assault, it may feel like we don’t need to talk about Bill Cosby anymore. We’ve talked about him enough.

What we haven’t done, though, is fully process Bill Cosby and how to reconcile his legacy as both one of the most significant, influential entertainers of the latter 20th century and a sexual predator who drugged and assaulted at least 60 women over five decades.

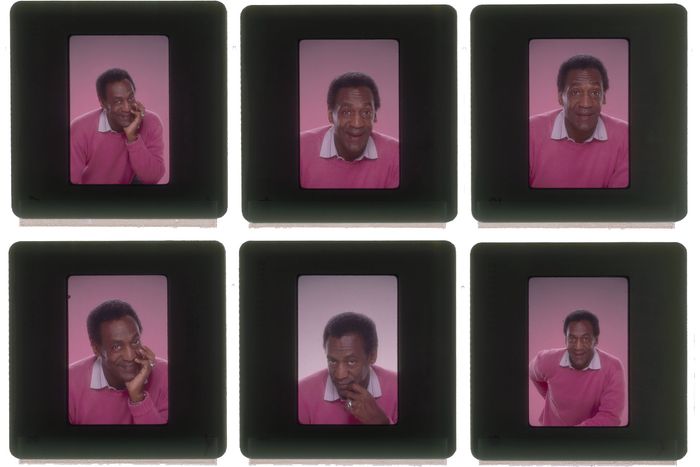

Comedian W. Kamau Bell, former host of CNN’s United Shades of America, forces that processing to continue in the four-part docuseries We Need to Talk About Cosby, which debuts Sunday night on Showtime. Via a consideration of Cosby’s career and transgressions, alongside interviews with academics, comedians, journalists, people who worked on The Cosby Show, and survivors of Cosby’s assaults, Bell, who directs, attempts to merge the two sides of Cosby into one comprehensive portrait of a human being. It’s a multi-episode conversation that’s thoughtfully and sensitively handled, and rightly places emphasis on how Cosby’s downfall has affected the Black community. It is also transparent about how conflicted Bell and others remain when it comes to how to define this comedian, a feeling that ultimately interferes with the series reaching the strong conclusion it seems to be setting up. (Not everyone is conflicted. When Bell asks several of his sources to describe who Cosby is now, Renée Graham, associate editor of the Boston Globe, responds, without hesitation: “He’s a rapist who had a really big TV show once.”)

The most vital service Bell performs in We Need to Talk About Cosby is to lay out a timeline of Cosby’s rising stature in pop culture over the years, from I Spy star to Dr. Heathcliff Huxtable on The Cosby Show, right alongside the dates when he preyed upon unsuspecting women. Presenting the information in such a straightforward way puts it plain: While a multitude of kids were loving Fat Albert every Saturday morning and comedy nerds were memorizing the dentist bit in Bill Cosby: Himself, Bill Cosby was routinely assaulting women without facing consequences of any kind.

“Bill Cosby, it seems to me, has been leaving something like breadcrumbs all throughout his career, pointing to his guilty conscience,” says Kierna Mayo, former editor-in-chief of Ebony magazine, in episode one. That idea is threaded throughout We Need to Talk About Cosby as Bell effectively characterizes moments from Cosby’s stand-up and TV shows as the equivalent of emergency siren emojis. There’s the famous Spanish fly routine on the 1969 album It’s True! It’s True!, a bit he was still getting mileage out of in 1991 during an appearance on Larry King Live. (Bell wryly notes that Cosby yukked it up with King about how you need to slip “only a pin-drop amount” of Spanish fly into a woman’s drink to get her to sleep with you, all while promoting his latest book, Childhood.) More breadcrumbs are sprinkled throughout We Need to Talk About Cosby, including the decision to make The Cosby Show’s Cliff Huxtable an ob-gyn who works out of his own basement, and another Cosby Show scene in which Cliff brags about how his barbecue sauce makes people horny.

Bell also highlights the ways in which Cosby’s image stood at odds with who he actually was in other contexts. Episode two focuses in large part on the way Cosby built an image as a teacher and education advocate by creating Fat Albert, frequently appearing on shows like Sesame Street and The Electric Company, and earning a Ph.D. in education from the University of Massachusetts. The doc points out that, technically, Cosby never finished his undergraduate studies at Temple University (he eventually earned an honorary degree) and that questions were raised about whether he actually wrote his Ph.D. thesis himself, a detail that adds a shadow of hypocrisy to Cosby’s history of lecturing people, Black ones in particular, about the importance of a proper education.

We Need to Talk About Cosby excels at this sort of context, illustrating how Cosby worked to make his comedy palatable to the broadest possible audience (read: white people), while also acting as a force for change. Calvin Brown talks about becoming the first Black stuntman in Hollywood, thanks to Cosby’s insistence that his double on I Spy be Black. (Prior to that, white stuntmen would have their skin painted a darker color when they needed to double for Black actors.) Others comment on Cosby’s commitment to making sure Black artists and professionals were employed at all levels on his sets. Bell contends that it was a combination of that loyalty to the Black community, popularity that transcended racial lines, and the warm affection he earned from children that laid a foundation of trust, enabling Cosby’s dark side to thrive outside of the spotlight’s reach.

Every survivor who appears in this docuseries says she initially felt comfortable with Cosby because of his reputation as someone likable and decent. Many say they stayed silent about what happened to them because they doubted they would be believed, precisely because of that reputation. Cosby’s career in entertainment acted as a protective force field. “When you look at the number of stories of women who have come forward saying Bill Cosby assaulted or raped them during this time,” Bell says in episode three, as he lays out another timeline focused on the 1980s, “and then you look at the number of accolades he got, you see that they skyrocket together.” As much as We Need to Talk About Cosby is specifically about Bill Cosby, it is also about broader concerns, like the way deification of celebrities in our culture becomes a permission slip for looking the other way, for individuals as well as institutions and entities within the entertainment industry.

Once the nature and breadth of Cosby’s heinous acts became more public following comments made by Hannibal Buress in 2014 and a cover story published in 2015 in this magazine, more and more women began to talk to the media about their specific Cosby stories. While we’ve heard or read some of these stories before, having them repeated here makes it clearer how frequently Cosby plucked his alleged victims from many corners of his professional universe, usually with promises to mentor them. It’s a story told over and over, by Patricia Leary Steuer, a University of Massachusetts alumna and aspiring singer who says she was drugged and assaulted by Cosby after meeting at the same institution where he earned that Ph.D.; by Lise-Lotte Lublin, a former model who says she thought she was being mentored by Cosby; and Lili Bernard, a young actor who sought out a larger role on The Cosby Show.

All of this could feel extremely exploitative and revictimizing were it not handled with the care that it is. Survivors are given the space to describe what happened to them for several minutes, at their own pace. When Bernard, who has told her story before and filed a lawsuit against Cosby, doesn’t feel comfortable going into the details on-camera, that wish is respected.

At the same time, some crucial questions are not fully answered in We Need to Talk About Cosby. Several sources suggest that people who worked on The Cosby Show were aware of Cosby’s behavior and enabled it. “You can’t do what he did unless you have a lot of people supporting it,” says Eden Tirl, who played a small role as a cop in an episode of The Cosby Show and was the target of inappropriate behavior by Cosby in his dressing room. The extent to which enabling occurred, particularly on the set of one of the most beloved and widely watched sitcoms of all time, demands some follow-up.

Most frustratingly of all, in the end, after persuasively illustrating over four hours that this artist and this man are intertwined, Bell decides the best option is to keep them separated. Returning again to the question he raised about how to think about Bill Cosby now, he confesses, “I wanted to hold on to my memories of Bill Cosby before I knew about Bill Cosby. I guess I can, as long as I admit, and we all admit, that there’s just a Bill Cosby we didn’t know.” He suggests that if we can absorb the lessons taught by the good Bill Cosby, then we can create a world where bad Bill Cosbys are less likely to exist. Which: sure, maybe. But that’s a pretty pat note to end on given the complicated, knotty analysis that has preceded it.

The much harder but more honest thing to do is acknowledge that there is no division — or, as Jelani Cobb, writer and Columbia University professor, puts it, “Some people tended to see it as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I think that you could make an argument that it’s all Mr. Hyde.” If you ever admired Bill Cosby, it may hurt to hear that. But just about everything in We Need to Talk About Cosby, excluding Bell’s own conclusion, suggests that Cobb is absolutely right.