This piece was originally published on September 10, 2020. We are republishing it following the news of Richard Lewis’s death on February 27, 2024. You can also read our appreciation of Lewis’s influential stand-up work here.

When the NBA season was temporarily suspended on March 11, 2020, the basketball podcasting community was left at an impasse: What to discuss? With the world increasingly mired in the sadness of a horrific pandemic, the co-host of my podcast and I decided to fill time with a fun distraction: rewatching old playoff games from our favorite childhood basketball team. Unfortunately, that team is the 1994 New York Knicks.

Luckily enough, we were able to find game broadcasts online that had the original early-1990s commercials, including gems like the all-new Mitsubishi Galant set to a jazz cover of “My Favorite Things” and a sultry, bordering-on-risqué spot seemingly voiced by Billy Zane for Acura (“Some things are worth the price”). However, one commercial distinguished itself as an innovator and pioneer. One commercial reimagined the possibilities of product branding and celebrity endorsement. One commercial featured Richard Lewis waxing poetic about a juice box for adults.

Our first encounter with the BoKu fruit-juice commercial, “Man of the ’90s,” left us speechless and required a half-dozen rewatches. Many things leapt off the screen: the dark, edgy set aesthetic and silhouette lighting. Lewis’s flowing mullet and all-black attire. His direct address to the camera, lamenting the common adult problem of showing up to a party and being forced to choose between Coke or Pepsi (“This isn’t right!”). But Lewis’s bleeding-heart declaration, “It’s my undeniable right as a man of the ’90s to quench my thirst in my own way,” while wearing what appeared to be a utility belt of juice boxes, catapulted an otherwise quirky commercial into a different stratosphere of cinema. This was art, a personal and brand manifesto.

We had to know more. Were there other ads? How, we wondered, did this happen?

“I’ve been doing this for 52 years, and when I got an email from my publicist that someone from Vulture wants to do something about BoKu, I thought I had died and gone to heaven; a fucking practical joke,” Richard Lewis says on the phone.

BoKu Fruit Juice Coolers debuted in November 1989 in 12-ounce packages with grown-up flavors like white grape raspberry, orange peach, and black cherry white grape. While juice-box titans like Coca-Cola’s Minute Maid and Hi-C were focused on satiating the school-aged masses, McCain Citrus, BoKu’s parent company, looked outside the box to a thirsty, untapped consumer demographic: fruit-juice-loving adults.

“McCain is and was a Canadian company that was really using the U.S. as an expansion market,” Bret Jenkin, former product manager at McCain, tells Vulture. “So they were very anxious to get this going. The environment early on, in the early ’90s, was growth.” The company planned to achieve that growth through BoKu’s advertising pitch to adults: larger containers, complex flavors, no straws, and Richard Lewis.

“We felt we had to be a little disruptive — as the new player in town, you’re going out and competing with Ocean Spray and Welch’s and all these other well-known brands. We had to be a little bit irreverent,” former BoKu marketing executive Nick Andrus explains. The idea of a celebrity spokesman was discussed at length. “Because we were looking for that irreverent approach, we thought of a comedian — somebody that’s a little bit outlandish, a little bit different, has some crazy ideas, doesn’t dress like everyone else.” They felt Lewis’s comedy and all-black wardrobe suited the brand identity. “He was in that target audience age group at the time. He seemed like a natural fit,” Andrus says.

“I mean, I don’t like fruit juice,” Lewis says. “I’m not a fruit-juice fan, so for me to have pulled this off is like … De Niro putting on 70 pounds for Raging Bull. I’m the De Niro of commercials with this one.”

Lewis starred in seven, as the tagline went, “slightly over the edge” commercials for BoKu from 1990 to 1993, at the height of his celebrity. “I was in the middle of a four-and-a-half-year run with Jamie Lee Curtis,” Lewis remembers of his reign on the ABC sitcom Anything But Love. “I was doing concerts, Carnegie Hall, and all of that. So it was one of those high points in what is normally a career that goes up and down and big and low and all of that shit.”

BoKu’s advertisements (the name is a play on beaucoup, by the way — French for “very much”) featured Lewis venting about the trappings of his life: an overbearing mother, wild nights out with friends, and fractured romantic relationships. “Everything was from hell. Women and dates from hell, my family from hell, my childhood,” says Lewis. The campaign effectively gave him an unencumbered platform to perform his angst-ridden stand-up, while presenting BoKu as the un-carbonated, therapeutic cure-all to his very adult problems.

“They wanted me to be me, y’know? To say that I’ve been typecast would be an understatement,” he says. “That’s what they wanted — Richard Lewis, a stand-up comedian who touches his head a million times like a woodpecker.”

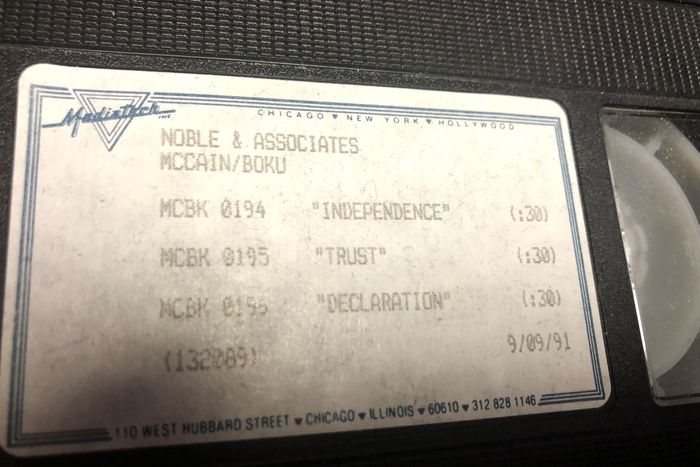

Lewis insists the commercials were the result of collaborating with “hip, brilliant copywriters” from ad agency Noble & Associates, who would present him with some ad-copy framework in the form of topics and themes to riff and tell jokes about. He appreciated the freedom. “They allowed me to inject my words,” he says. “You usually don’t get that opportunity. I don’t do anything unless I can do that.”

“There were terrific copywriters who were able to say, ‘Look, we got Richard, we love his humor. Let’s use that as much as we can,’” he adds. “They [allowed] me to be myself.”

The commercials featured Lewis advocating for beverage independence while railing against the tyranny of carbonation (“Belching is for babies!”), bemoaning juice-intolerant ex-girlfriends, and recounting his depressing childhood birthday parties (“No wonder I need a BoKu!”). Lewis says he rewatched all the commercials on YouTube the night before we spoke. “They were pretty trippy. They were funny,” he says. “Quite frankly, I thought I was having a nervous breakdown watching them all at once.”

And the ads were a hit. “It just took off like a rocket,” says Jenkin. He adds that BoKu’s popularity was tied to Lewis to the extent that the brand’s peak in sales coincided with a season-three peak in Lewis’s arc on Anything But Love: the night his character finally slept with Jamie Lee Curtis’s character in March 1991. “It was a chart we looked at a few times.”

“It got to the point where I would be walking down the street after being in the first season with Jamie Lee Curtis, top-ten show, sold-out Carnegie Hall, and cab drivers would go, ‘Hey, where’s your BoKu?’” recalls Lewis.

While the commercials were a hit — BoKu sales surged to $14 million from 1990 to 1991, up 90 percent with Lewis at the helm (Jenkin calls it “the great spike”) — the brand still failed to reach the popularity of its more well-known competitors like Snapple and Tropicana. Pressure mounted from within McCain to parlay the success of BoKu into bigger things. Specifically, large glass bottles.

“We really had to leverage this brand and the expense of the investment in advertising,” says Jenkin. “They took [BoKu] into glass, multi-serve containers, 48 ounces.” But it didn’t work. By mid-1993, BoKu’s share of the juice-box market was virtually nil. After a brief experiment with a lightly carbonated watermelon beverage called BoKu Melange, Jenkin says, “Everyone moved on. Richard moved on.”

McCain Citrus pivoted to more kid-centric brands, including a beverage called Zippin, which was test-marketed in 1996 with spokesperson Scottie Pippen but ultimately failed to launch. By April 2000, McCain Citrus was acquired by Pasco Beverage Group.

I try to explain to Lewis how I wound up knee-deep in a rabbit hole of BoKu, and he offers a guess: “Opium.” No, I say, even better: the playoff run of the 1994 New York Knicks. “I was there. I went to both games in Houston. We won one and lost one,” remembers Lewis of the ’94 NBA Finals, a series the Knicks lost in excruciating, heartbreaking fashion to Hakeem Olajuwon and the Houston Rockets.

Lewis and the New York Knicks, of course, are inextricably linked — he is one of the team’s most high-profile superfans, a staple of Madison Square Garden’s “Celebrity Row” throughout the ’90s. Lewis’s February 1991 memoir-style New York Times op-ed, “Trust Me, Babe, It’s Gonna Be Our Year,” reads like a love letter to New York basketball crossed with commercial copy for BoKu: “I live for just two things. For the Knicks to win another championship and to find a woman who won’t inevitably find the right moment to pour lamb’s blood over my head in front of close friends.”

In the end, like the ’94 Knicks, BoKu was a fever dream — a seemingly impossible confluence of talent, time, and place; a cultural and historical anomaly. It’s Laettner’s shot, the Miracle on Ice, Buster Douglas dropping Tyson. Yet like those Knicks — the most beloved basketball team the city has seen in 30 years, a team whose brief flirtation with immortality left fans reimagining the possibilities of hope — the legacy of BoKu lives on in its iconic commercials, and in any moment wherein an adult enjoys juice unencumbered by a straw.

“‘We’re talkin’ pull tab!,’” Lewis says in reminiscence. “I was very proud to endorse that, by the way.”