In Everybody Street, Cheryl DunnÔÇÖs 2013 documentary about New York street photographers, Ricky Powell, the downtown fixture who recorded the supernova of hip-hop in the mid-1980s, lays out the philosophical parameters of his process: ÔÇ£Man, waking up, making sure you wake up in the daytime, putting your pants on, making the calls, getting out of the house, maneuvering. You know I donÔÇÖt take those for granted. I have to be prepared, because a dope shot may arise even when I just go to the deli, and it happens.ÔÇØ

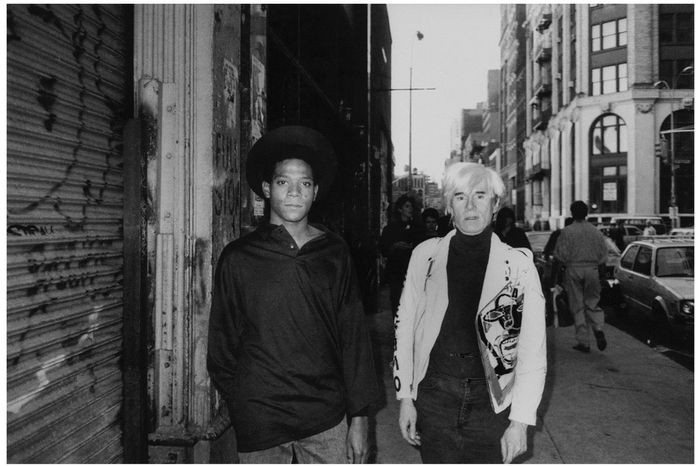

By his own account, Powell, who was found dead in his longtime West Village apartment on Monday at age 59, became a famous photographer by accident. He was present at a time in the cityÔÇÖs history now regarded as mythological: the confluence of the downtown art scene and uptown style writers, where you could see Jean-Michel Basquiat walking by your lemon-ice stand and ask him to pose for a career-making flick as he dug in his pockets for change. Powell wasnÔÇÖt a street photographer in the mode of Winogrand or Meyerowitz. He wasnÔÇÖt overly interested in the balletic collision of the crowd. Nor was he a paparazzo, chasing down celebrities. He worked somewhere in between┬áÔÇö ÔÇ£the raparazzo of the Village,ÔÇØ he called himself ÔÇö┬ádocumenting the class of young and ascendant artists and musicians and adjacent characters who together made up the downtown New York demimonde, bouncing from Patti AstorÔÇÖs Fun Gallery to nightclubs like Danceteria and Paradise Garage, taking off-the-cuff snapshots of people like Keith Haring, Laurence Fishburne, and Madonna when they were merely somewhat famous, instead of untouchably so.

Powell was a New York lifer, born in Brooklyn and raised in Greenwich Village, an alumnus of LaGuardia Community College and Hunter College, where he received a degree in physical education and played on the schoolÔÇÖs basketball team. Powell bounced around New York aimlessly after graduating, filling odd jobs ÔÇö dog walker, substitute teacher, bike messenger, ice vendor. Aside from touring with the Beastie Boys, he never left the city. For the past 30 years he lived in a small studio apartment on Charles Street in the West Village, where he was a familiar and voluble presence, generous with his time and eager to kibitz, his transistor radio aloft and tuned to Jazz 88.3. He could be protective of the city, in the way native New Yorkers tend to be, and bristled at the influx of the ÔÇ£New Jack cornballsÔÇØ ÔÇö the new money that could make the neighborhood seem like a Hamptons-lite.

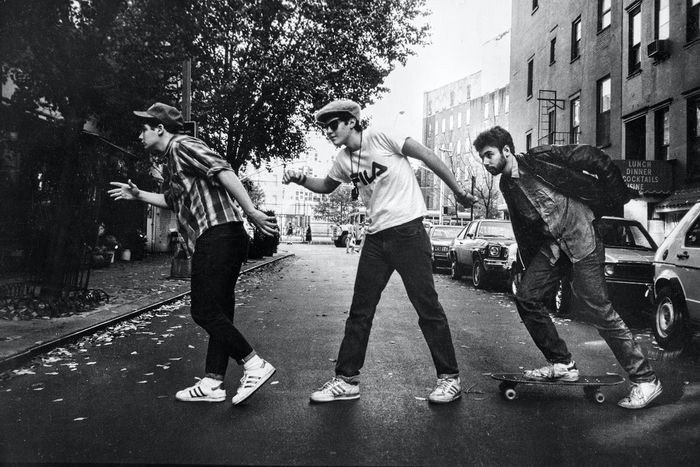

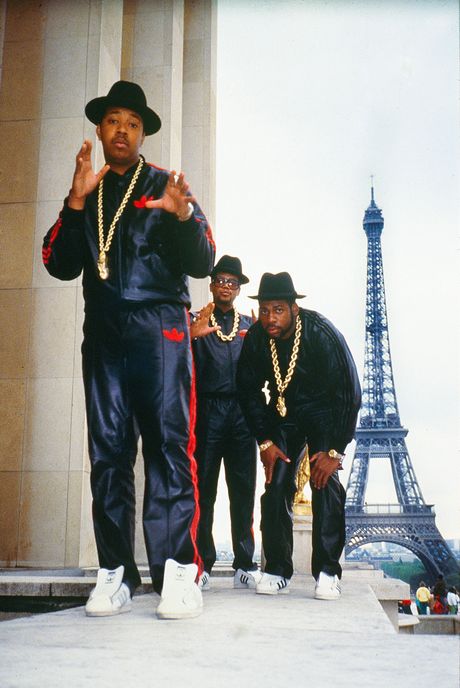

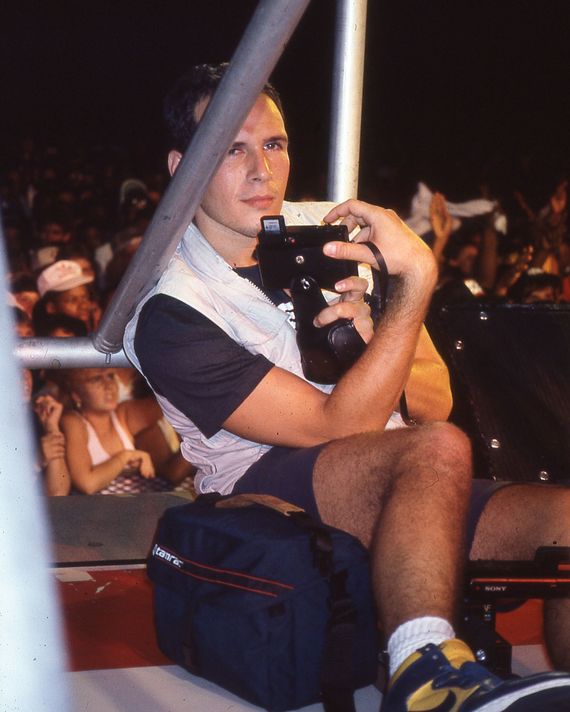

He got his start in photography, as goes the story he often retold, out of spite. After getting dumped and finding a Minolta his ex left behind, he simply resolved to take pictures and become someone doing it. He was self-trained, and many of his images betray a complete disregard for composition or framing or lighting. But they were no less spectacular for it, and probably were better served by being unburdened by the weight of methodology. PowellÔÇÖs method was being there, a kind of relational aesthetic for which he had uncanny talent. He described his style as ÔÇ£pro photos on a hang out tip.ÔÇØ Within a year of picking up that first camera, he had parlayed a friendship with the Beastie Boys ÔÇö Powell and Adam Horovitz attended P.S. 41 in the Village together ÔÇö into a gig documenting their tour with Run-D.M.C.

Powell occupied a rare position as a white guy who was able to move within the largely Black hip-hop culture. Much of that access can be attributed to his connection with the Beastie Boys, outliers who traced a similar path. But Powell possessed a certain sincerity that people seemed drawn to, a quality Powell himself joked he never fully understood. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know how I used to hang out with these dudes,ÔÇØ he said in Everybody Street. ÔÇ£Except they knew I was down.ÔÇØ

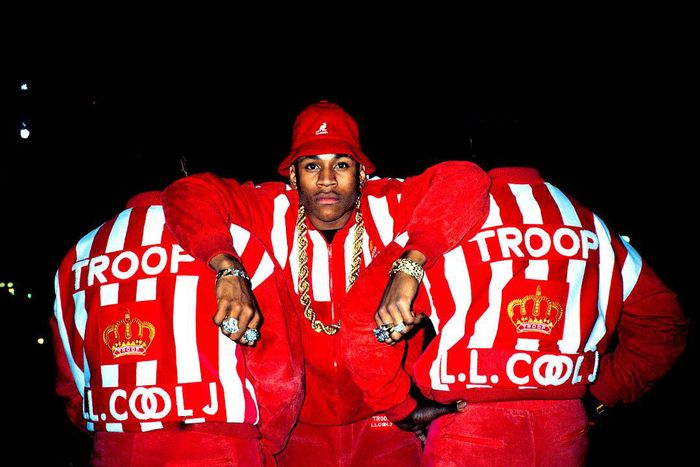

ÔÇ£I was never sure that Ricky was white,ÔÇØ LL Cool J says in Ricky Powell: The Individualist, a documentary about PowellÔÇÖs life set to premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival this year. ÔÇ£I wasnÔÇÖt sure if he was a light-skinned Black guy. He understood the culture, he understood the language. Ricky was the right guy at the right time.ÔÇØ He photographed those vanguard artists ÔÇö LL, Run-D.M.C., Public Enemy, EPMD ÔÇö and the era of fat dookie ropes and Kangol buckets at a time before stylists and marketing strategies, effectively shaping much of the popular visual conception of the genre. His images of them are quick and loose, the full energy and humanism of the music seized within the frame.

ÔÇ£There are a variety of qualities that make a good street photographer,ÔÇØ Dunn tells Vulture. ÔÇ£Maybe youÔÇÖre technically proficient, maybe youÔÇÖre the fly on the wall, maybe, like Mary Ellen Mark would say, you have the advantage of being let in the door. Ricky would say anything to anyone ÔÇö famous, non-famous. The ability to go up to anyone and just shoot the shit ÔÇö he could do that, and people would be charmed by that, and he would get their picture. That was his ace quality. There are characters in those pictures, but heÔÇÖs one of those characters. The people he was drawn to, heÔÇÖs one of them.ÔÇØ

Powell was not self-serious. In his later years, he adopted a look of artful dishevelment: too-large pants pooling above his Converse All-Stars and an obnoxiously loud baseball cap with humongous embroidery, like W 4TH (for the subway station) or THE NEW YORK CRIMES (in the newspaperÔÇÖs gothic font), or REAL NEW YORKER (in the magazineÔÇÖs), the cap always cocked to one side, and had taken to posing for photos with pinched fingers pursed to his mouth, as if he were puffing on a phantom joint, a pose he referred to as ÔÇ£the invisible jazz cigarette.ÔÇØ He referred to himself with winkingly self-deprecating nicknames like ÔÇ£The Lazy Hustler,ÔÇØ and ÔÇ£Uncle Sloppy,ÔÇØ becoming something of a down-tempo ambassador for the neighborhood, even sometimes leading casual walking tours.

ÔÇ£He really was all about the city,ÔÇØ Tony Arcabascio, one of the founders of the New York streetwear label Alife, who knew Powell since the mid-ÔÇÖ90s, tells Vulture. ÔÇ£When we would walk around the city, he always made me feel like a tourist, as much as I grew up here. Sometimes I would pretend to know what he was talking about, just so I didnÔÇÖt come off like some punk. He knew everybody. He knew every place. He knew the heavy hitters, but he also knew the homeless. For him, they were equally important. They were both worthy of presenting the city that he loved. HeÔÇÖd take a picture of the UPS guy the same way he would Madonna.ÔÇØ

In many ways, Powell represented a version of the city that has all but faded away, the crucial connections made at clubs and galleries now muffled by real-estate concerns or mediated by screens. Powell took pride in being able to offer a bridge. ÔÇ£He knew as well as any of us whose been around long enough that the thing about New York is it fuckinÔÇÖ changes,ÔÇØ Arcabascio says. ÔÇ£I think Ricky knew thatÔÇÖs what he was there for ÔÇö to school you and let you know what the old New York was all about, but he was also there to document the new New York.ÔÇØ

In interviews, Powell likened street photography to his ever-present transistor radio. ÔÇ£Well, photography, all you gotta to do is step out your house, and there will always be pictures to take,ÔÇØ he said. ÔÇ£The playlist is infinite.ÔÇØ