Last week, after a Los Angeles screening of the wildly premised biopic Better Man, I saw a number of viewers get out their phones and immediately Google the film’s protagonist. For the past two hours, they’d watched the real-life story of Robbie Williams — a British pop singer who’s sold over 75 million records — acted out by a CGI monkey. Perhaps my fellow moviegoers needed further confirmation that the star of Better Man was, in fact, based on an actual person.

Let’s also assume the Googlers were Americans, since, to most Britons like myself, Williams’s story is as culturally ingrained as the rules of football. Ever since Better Man’s wide release, Americans’ further incuriosity toward the film and Williams has revealed itself, splitting viewers into two camps. On one side: the Yanks, both confused about who Williams is and gleeful that Better Man is bellyflopping at the box office. On the other: the English, who are calling out the provincialism and insecurity endemic to American culture, and who don’t believe a life without Williams is worth living. All of this, of course, falls right into the pop star’s pocket. He’s a trickster sustained by both hate and admiration in equal measure.

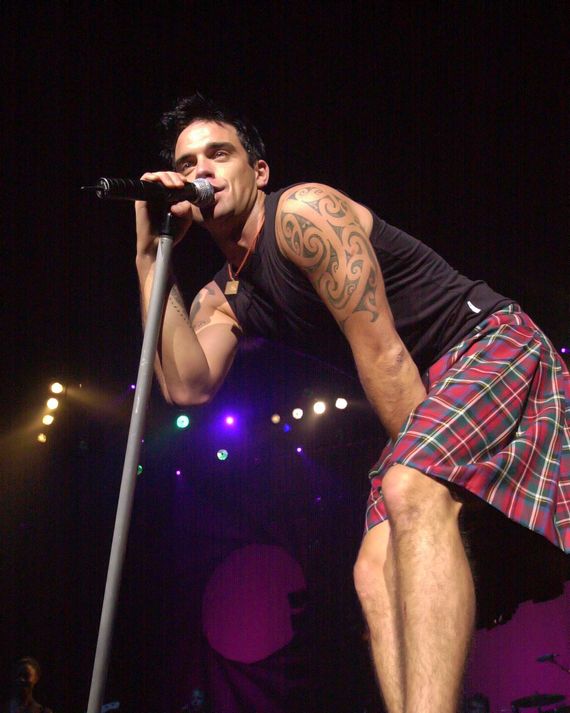

Born Robert Peter Williams in the unremarkable city of Stoke-On-Trent, one of the best-selling male British solo acts of all time first found stardom as a teenager in the ’90s boy band Take That. The group performed tightly choreographed and exuberantly camp anthems, but Williams, an off-kilter and often out-of-key performer, jarred against the rigidity of the band. He eventually left Take That in 1995, an event that caused the charity Samaritans to set up a helpline for crestfallen fans. Leaving would also set the foundation for the next breakneck chapter of Williams’s career. His debut album, Life Thru a Lens, spawned several supersonic hits, including “Angels,” a track that began closing out everything from school discos to funerals. By the 2000s, Williams had become as fundamental to England as bad teeth and blinky awkwardness. He was, as he stated on his 2002 single “Handsome Man,” the one who put the “Brit” in “celebrity.”

Yet despite his status overseas, Williams’s many attempts to break Stateside have repeatedly fallen flat. Whether Better Man finally pulls it off is an open question. Until then, I, a lonely Brit in L.A., have a sharp desire to teach this country about the Robster and everything that’s made him the patron wanker of bighearted buffoonery.

.

His Survival Arc

Williams’s rise is a rare story of meritocracy at work. We love that he grew up in Stoke-on-Trent — a place of working-class pride that Brits can safely exoticize — and how, when he joined Take That, he transcended that upbringing to join London’s latte-drinking elite. We love how forthright Williams has been about his battle with alcoholism and how he resisted it so sharply (he’s been sober for over 20 years now). We love how his songs are all-conquering anthems that turned small life large: “I hope I’m old before I die / Well, tonight I’m gonna live for today,” he sang on “Old Before I Die.” But most of all, we love that there is nothing particularly transcendent or exceptional about Williams. What he may lack in technical exceptionality, he makes up for with a zany and overzealous desire to entertain. He’s an everyman with a semi-theatrical singing voice. By his own admission, he’s cabaret: someone with the vocal talent of a cruise-ship performer who happened to find colossal success. Williams gleefully forces our gaze upon him and his own try-hardness. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the music video for “Rock DJ,” which sees Williams literally peel off his own flesh in order to get the audience’s attention.

.

His Lovable Dickheadedness

Cocky, in-yer-face, and devilishly mischievous, Williams is explicitly committed to the philosophy of just havin’ a bloody good laugh, mate. Seemingly made in a petri dish of cigarette ashes and watered-down lager, his vernacular comes straight from the British pub. He is routinely cheeky. Take, for instance, the time he shouted, “I’m rich beyond my wildest dreams!” at a press conference after his record-breaking £80 million signing with EMI in 2002. His main function is to remind us that nothing — including seriousness itself — should be taken seriously. A few choice examples:

- On inventing queerbaiting: “An awful lot of gay pop stars pretend to be straight. I’m going to start a movement of straight pop stars pretending to be gay.”

- On the then-51-year-old Madonna: “She looks amazing. I can’t believe she’s 89 and looks like that.”

- On his wife giving birth to his daughter: “It was like my favorite pub burning down.”

- On mediocre postmarital shagging: “The sex is nothing to write home about. It’s a shame because my mum loves those letters.”

- On his success: “I am the only man who can say he’s been in Take That and at least two members of the Spice Girls.”

.

His Confessional Approach

As often as Williams’s songs are funny, they are also self-flagellating, sad, and insecure. Williams has always sourced his punch lines from a place of pain. His songs make plain what his arrogance, brashness, and vivacious assholery try to conceal: He is a man full of irreconcilable contradictions who longs for emotional simplicity. “I just wanna feel real love / feel the home that I live in,” he sang on “Feel,” which also features one of the all-time greatest confessional lyrics: “I don’t wanna die / But I ain’t keen on living either.”

Williams brought to British music a self-revealing and revelatory confessional mode that is now ubiquitous. While the genre has devolved into safe narratives and pop therapyspeak, there was a real sense of risk and ambivalence to Williams’s lyrics. In one moment, he could be bored and dispassionate; in the next, he’d inflate feelings until they were one breath away from exploding. His songs convey such a rare level of emotional articulacy that they tend to draw some level of admiration — even if reluctantly — from just about every crowd. Kids feel spoken to in a way they’ve never before. Teenagers yearn alongside him. Divorced dads finally feel held.

.

His Exposing the Realities of Fame

Long before the knowledge of Britney Spears’s conservatorship inspired our broader reckoning with celebrity, Williams was Britain’s infamous anti-fame sage — which, of course, only made him more famous. His songs often cheekily broke the fourth wall, exposing the industry and its bigwigs’ desire to infringe their commercial logic upon his art. “We’ll paint by numbers, ’til something sticks,” he sang alongside Kylie Minogue on “Kids.” While it’s now common for singers to bemoan the dehumanization of the music business, Williams set an early precedent at a time when fame was at its most noxious and uncontested. His commercial peak coincided with an upsurge in celebrity interest and devaluation. While that caused an unprecedented skepticism of fame from the public, as well as a distinct lack of sympathy for anyone who experienced it, Williams’s was one of the few anti-fame voices who broke through. The more famous he became, the more he sang about how much it destroyed him, and the more people actually sat up and listened. “Yeah, I’m a star, but I’ll fade / If you ain’t sticking your knives in me / You will be eventually,” he chided on “Monsoon.” When you become famous, people tend to stop feeling sorry for you. That’s the case for everyone, except Williams. As Better Man lays out, he’s the performing monkey whose pain becomes our entertainment.