The Character: Alan Zaveri, the similarly time-loop-stuck companion to Natasha Lyonne’s Nadia Vulvokov. While Russian Doll begins with Nadia’s initial Groundhog Day moment, Alan is already living through his recurring cycle when he meets Nadia in the final minutes of the third episode, “A Warm Body.” Although Alan seems to have embraced his time loop and the opportunity it provides for a routine, he teams up with Nadia to investigate why they’re in this unique predicament together. When the series’ second season opens, four years later, Alan has a new mustache, is going on dates set up by his mother (Lillias White), and has loosened up a bit — before getting pulled into Nadia’s latest reality-defying adventure.

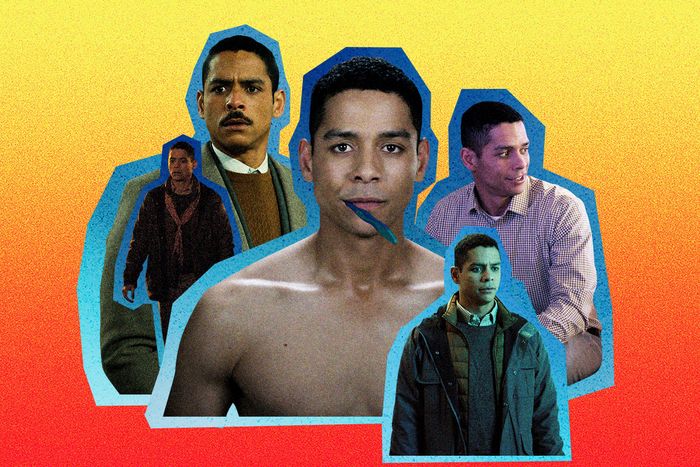

The Actor: Charlie Barnett, 34, a graduate of Juilliard, where he became best friends with Samira Wiley, who co-starred with Lyonne on Orange Is the New Black. He was a main cast member on Chicago Fire from 2012 to 2015, and he had a significant supporting role in the season-five OITNB episode “The Reverse Midas Touch.” Since the first season of Russian Doll premiered in February 2019, Barnett has appeared as a main cast member in the Netflix miniseries Tales of the City and NBC’s Ordinary Joe and as a recurring cast member in the second season of You and the eighth season of Arrow.

Essential Traits: Mannered and tidy, ritualistic and self-defeating, vulnerable and raw. Alan — for whom Russian Doll never specifies a job — is devoted to his fish, Boba Fett; his doctor mother; and his Ph.D.-pursuing girlfriend, Beatrice (Dascha Polanco). After he’s shattered by the news of her infidelity, his obsessiveness tips into self-destruction, including cake bingeing, nascent alcoholism, and cleaning Nadia’s apartment without her permission. His loyalty and love are unconditional, but he needs to extend them to himself.

‘The Odd Couple of It All’

In September 2017, when Netflix gave an eight-episode straight-to-series order to Russian Doll co-creators Lyonne, Leslye Headland, and Amy Poehler, Alan Zaveri did not yet exist. The show focused primarily on Lyonne’s character, Nadia, and her attempts to escape a party where she is the guest of honor. When Russian Doll assembled its all-female writers’ room, including executive producer and writer Allison Silverman, Alan became “an invention of the room,” spearheaded by Silverman, Lyonne says. The character was partially inspired by “riffing and joking” about Lyonne’s then-relationship with fellow actor, writer, and comedian Fred Armisen.

“I remember us joking about the Odd Couple of it all,” Lyonne says. “Fred is such a tidy fellow. Fred’s glasses are always very clean. Fred and I are still close and love each other very much; we were together for seven years. I’m somebody who wants to roll the windows down when driving and turn the music way up and chain-smoke out the window, but Fred likes a climate-controlled vehicle where the music is at the right volume. It’s a focus, like an album; it’s not just turning the radio around every five seconds. That idea was making us laugh. That partnership historically works so well.”

Once Lyonne and Headland began “falling in love with Alan as an idea,” Lyonne thought back to meeting Barnett at Wiley’s March 2017 bachelorette party and realized she “could really see him” as Alan, she says. Both Lyonne and Barnett credit that to their candid conversations amid the bacchanalia of Wiley’s celebration, and Barnett adds that certain elements of his journey (“We talked a lot about alcoholism and addiction”) made their way into Alan’s molding.

“It’s hard to say where the acting notes and the personal-journey notes end or begin,” Barnett says, “and those are the ones that become most impactful.”

“What he brought was such beautiful depth and soulfulness,” Lyonne adds. “The material certainly did not change in his casting.”

Once Barnett signed on, he, Lyonne, and Headland had phone conversations about the series’ concept and narrative arc. In a fulfillment of the Odd Couple idea, Alan differed from Nadia in significant ways, but through the shared experience of their recurring deaths, each learned about the shortcomings of their current lifestyles and how they were obscuring or underserving essential elements of their personalities and pasts. Their friendship and compassion for each other encouraged this individual growth. “They are foils that push each other really far apart,” Barnett says. “I am always pulling her back from the ledge, and she’s always pushing me off. She is that extremity in life we all know so well, and I am the other side.”

Whereas Nadia is surrounded by friends and former lovers at her 36th-birthday party, Alan’s circle is constrained mostly to his mother, whose high expectations are somewhat stifling; his longtime friend Ferran (Ritesh Rajan), who happens to run Nadia’s preferred corner store; and Beatrice, who is cheating on Alan with her professor Mike (Jeremy Bobb). Nadia thrives on a kind of organized chaos in her personal life and domestic space, while Alan’s rigidity manifests in his stiff posture and the 45-degree angles of his apartment. Circles define Nadia’s world, from her Krugerrand pendant to the mirror she gazes into in the bathroom where her death loop always resets; squares are indicative of Alan’s perspective, such as the mirror where he restarts his own loop.

Once the pair teams up after Alan’s introduction in “A Warm Body” and his further contextualization in the fourth episode, “Alan’s Routine,” the two are often positioned with Alan on the left of the frame and Nadia on the right. While riding in elevators, walking around Tompkins Square Park, wandering through Maxine’s party, or shown in a split screen at their respective time-loop restart points, they’re aligned and bound together. “They were always in tandem. They’re kind of like these polar magnets — attracted, but they also don’t stick,” says season-one production designer Michael Bricker.

Embodying Alan

Barnett was eager to do something different from the usual network TV and was attracted to the “fucking hella uncomfortable position” of Russian Doll with its twisty narrative and demanding character work. Alan’s sensitivity and reactivity to his circle of family and friends were immediate draws as well, reminding Barnett both of himself (“Just feeling like he couldn’t hide his emotions, I related. I related hard-core,” he says) and — more abstractly — a layer of fungus growing deep in the earth. (“That is the largest living organism, and it’s interconnected throughout oceans. I think about that and humanity a lot.”) “It’s so much easier to play and explore and develop someone like Alan when you can relate,” Barnett says.

Max Richter’s rearrangement of Vivaldi’s “Spring 1” served as Barnett’s soundtrack as he went for long walks to learn Alan’s “tics, his tightness, his control,” the actor says. He thought about how his own father — who has a “minor, minor case” of Asperger’s — communicates and interacts with other people. Barnett emphasizes that he wasn’t trying to portray Alan as neurodivergent but that considering his father’s experiences gave him another perspective and helped him build “a lot of love for Alan.”

Every script inspired new questions. Barnett thinks Zaveri is an Egyptian surname, and he likes to imagine Alan’s father as hailing from that country. (Barnett, who describes his own father’s mustache as “the epitome of masculinity,” is adopted and has Black and Irish ancestry.) Of Alan not having a canonical career, Barnett theorizes that he had tried to follow in his mother’s footsteps and pursue medicine but “ended up” in human resources. All these questions populated the booklets, lists, timelines, and other “plan-heavy” materials Barnett brought to the set to organize his voracious curiosity about his character. It was all very Alan, he admits, and it didn’t exactly align with the approach of Lyonne, Headland, or director Jamie Babbit. They encouraged him to “let all this go … ten, 12, 50 more times,” Barnett remembers, and he shares a moment in which Lyonne pulled him aside to assure him, “What you’re going through, it’s very Alan. You need to take a step back and know that you’re good enough.” But the disconnect between who he thought Alan was — his tone, his neuroses, and his stiffness — and the more freewheeling looseness he was directed to adopt was a challenge to overcome.

“It became this tug and pull on my heart,” Barnett says. “It was difficult. I’m not going to lie.”

Barnett describes himself as “a little bit of an osmosis performer,” and the blurriness of the line between himself and Alan, a fluidity created by how “so much of our own lives and our own identities were literally written into these characters,” was variously an asset and a detriment. Sometimes Alan’s sense of fear and loneliness didn’t come through clearly enough, the actor thinks, as in his line delivery of “I die all the time” from “A Warm Body.” That elevator crash was the first scene he shot for the series, and “even watching it now, I feel it was a little too deadpan, a little ambiguous,” he says.

One strength of Barnett’s performance, though, is Alan’s unlikely humor, which initially comes from his (justified) sass and aggression toward Beatrice and Mike for their affair and later emerges through his quirky chemistry with Nadia, who challenges some of his self-pity. Certain scenes work primarily because of his loose-limbed silliness and sincere grin, as when he proposes with Beatrice’s unwanted engagement ring to Brendan Sexton III’s mysterious (maybe magical?) Horse in the season-one finale, “Ariadne.”

And although the scene Barnett is proudest of — the one in which Alan admits to Nadia that he died by suicide in his first death, kicking off his time loop — is far more serious than his goofy embrace with Horse, the actor’s openness is essential to both. In episode six, “Reflection,” Barnett’s Alan is wound up and worn out from reliving the hours leading up to his first death, and he meets Nadia with a determined expression when she walks through the door. But when he starts to speak, his performance shifts into a different register, his teary eyes and halting line delivery communicating the distinctive vulnerability that drew Barnett to the character in the first place.

For Barnett to reach the honest place the moment needed, the scene took a few takes and a gentle prompt from Lyonne to access an experience from his college years. “That scene, as an actor, you’re looking at it and you’re like, Oh, it’s the cry moment. That kind of pressure can really eat at your mind, and God knows it can also rip open your heart in a really beautiful and powerful way,” Barnett explains. “It was a really hard moment because it is so true. I have tried to commit suicide in my life, and I have been on those ledges. Natasha pulled me aside and said that. ‘I know you’ve been there, and I’m not seeing that yet.’ I think realizing, Oh yeah, I don’t have to think about this one, as sad as it is, as hard as it is, helped. It’s one of those moments that that depression or that fear in your own self becomes your superpower because you’re like, I get to use it for good.”

“He’s got a real depth and well of humanity, and it’s very accessible in him,” Lyonne says of Barnett’s season-one performance. “The experience for all of us, being people, is a raw thing we’re trying to make sense of moment to moment. And his ability to both talk about it and communicate it, it’s like his heart gets transmitted into the camera. The camera can smell the truth, and it feels like the truth of his soul.”

Crafting Alan’s Sense of ‘Inoffensive Function’

The tight production schedule for Russian Doll left little wiggle room, and Bricker began designing the season-one look of the show with only the pilot script for inspiration — meaning he was initially unaware of Alan’s addition to the show. “Natasha and Leslye were like, ‘Oh, by the way, there’s this other character that you really need to consider,’” Bricker says. The concept for Alan became clear in the eventually scripted directive that his apartment be “everything Ikea” with a sense of unfinished sterility and “inoffensive function” that speaks to Alan’s discomfort in the world and his desire for guidance.

Bricker and his team found an apartment in the East Village where they could shoot on location — except for Alan’s bathroom, which was built back-to-back with Maxine’s on a soundstage — and filled it with Ikea pieces, including the various tables around his couch and the white shelving unit in his bedroom. Alan’s sense of inflexibility is reinforced with a square-shaped fish tank for Boba Fett, a square-patterned room-divider screen, and long floating shelves that slice up his living-room walls. Barnett — whose partner is also a production designer — praises Bricker for reaching out to him for his thoughts on the design of Alan’s apartment: “I have never, ever, ever, ever had a production designer call me prior to filming to say, ‘Hey, I’ve been working on the set. I want to show you designs and ask you what you feel like as a character living in this space.’ Never!”

And so personalized elements made their way in. Barnett provided books: David Magee’s Life of Pi, one of his own favorites, and Look Me in the Eye: My Life With Asperger’s by John Elder Robison, which Barnett’s mother had gifted him in connection to his father. Bricker selected kitchen decorations: a set of Hasami porcelain nested plates that create a series of concentric rings, which Bricker considers “the Alan version” of Nadia’s Russian doll, and a collection of four framed art prints that highlight a commonality between the time loopers. “In his kitchen, I took the cover of the Ariadne game Nadia designed; we printed it larger and cut it in four and then rearranged the pieces,” Bricker says of the images that hang over Alan’s sink. “No one has ever noticed, I think. That’s clearly a connection they had: She designed the game, he appreciated the game.”

For the second season of Russian Doll, which filmed in New York and Budapest, Diane Lederman stepped in as production designer. Another demanding shooting schedule and new ownership of the East Village apartment necessitated a major change: re-creating Alan’s space on a Budapest soundstage. Although measurements were taken of the original apartment so the new construction could be an exact duplicate, an expected challenge (which Lederman also experienced during her time on The Americans) arose in the conversion from America’s imperial system of measurement to the European metric system.

“When you translate inches to centimeters, you lose a little something,” Lederman says. “Even though I begged this Budapest team to work in inches and feet, they couldn’t wrap their heads around it and didn’t. The dimensions are slightly off, but happily, it wasn’t recognizable enough, and we did what we could to fix it.”

The four-years-later timeline allowed for some updates to Alan’s space, including an incorporation of more circles to indicate Nadia’s expanding role in his life and a revamped exercise area. But there was one suggested addition from a Budapest set decorator that Lederman vetoed. “She had amazing taste, a great eye, but she did this little bread display, and Natasha and I looked at each other like, Oh yeah, this would never be in America,” Lederman says. “And Alan certainly wouldn’t do this amazing croissant display in a basket with some napkins. This is not our character, but thank you.”

But Russian Doll fans looking for Easter eggs should keep an eye on the advertisements in the second season’s prominent subway car, Lederman says. A reference to Alan’s season-one cake made its way in, alongside others Lederman’s team developed on their own and numerous period-appropriate graphics her team borrowed from the New York Transit Museum, including a nod to omnipresent dermatologist Dr. Jonathan Zizmor, whose ads ran in subway cars from the early 1980s until his retirement in 2016.

The Mustache

“Do I need to be worried?” a mustachioed Alan asks Nadia in the trailer for the show’s second season, which will be available on Netflix on April 20 and is a twist upon the time-travel premise of films like Back to the Future. Four years after the events of the first season, Alan and Nadia have remained close friends (a “genuinely unconditional relationship” with “actual unconditional love,” Lyonne says). With a new opportunity at life, Alan is a little more loose, mischievous, and spontaneous — a personality shift that season-two cinematographer Ula Pontikos was excited to capture.

“In season one, he was very detached from his emotions and where he was in his relationships. It was part of his loop,” Pontikos says. “This season is about the discovery of what he really values and what he needs from his relationships and life. There was a very strong romantic line, and some frivolous moments of happiness and rediscovery where things were probably approached a little bit differently than regular Alan.”

The new facial hair is the most obvious sign of that change and is a holdover from a pre-COVID version of the season that would have included a “multiverse Alan,” Lyonne explains. “The thing that stayed alive from that story line was Charlie as Clark Gable. Happily, there is a major win there, which is the beauty and the glory of Charlie Barnett’s mustache.”

Lyonne and Barnett were in communication when the writers’ room was in session, and they discussed some of Alan’s new experiences in these seven episodes: a kind of rebirth in another bathroom, designed and built by Lederman with custom tile she created herself, and a transformational dance party that Pontikos and Steadicam operator Devon Catucci shot in Budapest in “this bunker four stories, five stories, six stories down, with no lift,” Pontikos says. “It was very challenging and sort of quite incredible.”

In those scenes and throughout the rest of the second season, Barnett seems more comfortable in Alan’s skin as Alan prioritizes himself, pursues a new love interest, grapples with the uncertain impact of a decision he makes without Nadia, and realizes his hopes and ambitions for the future. Barnett waited seven months after the first season of Russian Doll premiered to watch it in its entirety, but he has already watched this new set of seven episodes with his parents. He acknowledges that the process he used to enter Alan was perhaps purposefully self-punishing (“I was scared and beating myself up too much, and I probably didn’t need to do that”), but he also doesn’t wish it had gone any differently. “It was part of the process, and it brought a lot of what I needed for Alan to it. To say I would have one without the other or have it changed, that’s not really taking it in full,” Barnett says. “It became something else. The cactus grew a bloom.”